Story

Una Carta de Amor a Mi Comunidad

Nicki Gonzales’s love letter to the people who make us who we are.

Editor’s note: this essay was adapted from Dr. Gonzales’s State Historian’s Address, delivered at the History Colorado Center in July, 2022

In a tiny windowless adobe building in the hamlet of El Rito, Colorado, the leaders of the Land Rights Council of San Luis called a meeting to outline their new legal strategy. It was August 18, 1980, and the Land Rights Council leaders, Shirley Romero Otero, Ray Otero, and elder Apolinar Rael, spoke passionately in the meeting about the injustice they suffered fifteen years earlier, when a district court took away their community’s historic land rights to La Sierra, a 77,500-acre mountainous common land in southern Colorado. The district judge who issued the ruling in 1965 invoked the racist attitudes of the time, going so far to say that “those Mexicans needed to be brought into the twentieth century.” For the mountain people of El Rito (also known as San Francisco), their connection to the lands of La Sierra was vital to every aspect of their lives. It shaped everything from their diets and their homes to their history and spirituality. Losing their right to legal access was economically and culturally devastating, not only for them, but also for the people of the surrounding villages of San Luis, San Pablo, San Pedro, and Chama.

From their windowless adobe meeting room, the activists called their fellow community members to join their new lawsuit, Rael v. Taylor, which would challenge that 1965 ruling with the goal of winning back their historic rights. When asked to sign on as plaintiffs, however, those in the audience responded with silence. Many looked down at their feet. Some looked down at their hands. The American legal system had done them wrong in the past—why trust it now? Why pick up the fight when the obstacles seemed so insurmountable and when it was hard enough to just make a living each day?

Suddenly, a woman standing no more than four feet tall—a victim of childhood polio—steadied her crutches in both hands and rose to her feet. Her squeaking metal supports and her chastising words broke the deafening silence, as she made her way to the front of the room:

“Bueno cabrones, si usted hombres no tienen los huevos para firmar, dejame pasar.” (“Okay, bastards, if you men don’t have the balls to sign, get out of the way and let me pass.”)

The woman was Agatha Medina, and her husband, Ray Medina, followed her to the front. Agatha was the first plaintiff to sign on to the legal fight to regain the community’s 130-year-old land rights—rights they had fought to keep for generations. And following her lead, the community would fight to vacate the judge’s 1965 ruling. Others followed, and soon, ranks of people stood in line to sign their names to a historic petition.

Agatha shaped history that night. She would remain a critical presence in the lawsuit, and her chutzpah and fierce determination certainly always inspired me and many others. Her desire to fight for her community’s sacred relationship with the mountains they called La Sierra helped propel their community to victory years later. Agatha Medina passed away in October 2021. She was seventy-eight years old, and is still one of the bravest women I’ve ever known. Her story, like so many others, deserves to be told.

The Fort Lupton Girls Basketball team in 1921. My great great Aunt Flora Sandoval (later Abeyta) is the player on the top left.

Why do I start with this story? Why does it stay with me, after hearing it for the first time about twenty years ago?

For me, Agatha’s story highlights an important chapter in the civil rights history of our state. Her contribution to the history of the Chicano movement cannot be overstated, and her courage and determination to fight for the cultural and economic survival of her community gives us a truer, richer picture of our state’s past and elevates heroic figures to look up to in tough times. Learning her story directly from her shaped my own work as an activist historian and taught me that I have a responsibility to use any platform I have to amplify those histories that have been excluded.

I think a lot about community, but never more than during my year as Colorado’s State Historian. As a person born and raised in Colorado with a deep love for our state, I define my community as all of Colorado. But I’m also part of the Latino community, whose stories I share, and whose members reach out consistently with love and support, and who always share their stories with me. It is also my Regis University community who have supported my work and given me a framework of Jesuit values to help guide me through the years. This essay and the talk it was adapted from are love letters, or letters of gratitude, to all of my communities.

On a deeper, more personal level, this is a love letter to my family—to my parents, who have worked themselves to the point of exhaustion and have guided me by how they have lived their own lives. They inspired my sisters and me to get an education and raise families of our own with the same values. This is also a love letter to my boys, Danny and Teddy, to my sisters and their families, to my aunts, uncles, and cousins whose lives have shaped my world. To my grandparents and earlier ancestors whose dreams, sacrifices, and toil paved the way for my family to be here today. It is a love letter to my paternal grandmother, Margaret Lujan Gonzales to whom I dedicate all of my work as State Historian. She was a brilliant, athletic, strong single mother in Denver, who raised three boys in a city that was so different from the Denver we still call home. Though I never met her, during this past year I have felt her with me in ways I can’t explain. Every conversation I have had with community members who shared their stories has brought me to a deeper understanding of the life she lived and the challenges she faced and the courage and resilience she passed down to all of us.

Those who know me know that I have a favorite passage, which sums up my belief that we carry our histories with us, consciously and unconsciously. In 1965, James Baldwin—whose prophetic voice has been uplifted since the murder of George Floyd and the racial justice movements that have followed—wrote an essay in Ebony magazine called “The White Man’s Guilt.” In it, he wrote about the pervasive power of history:

History, as nearly no one seems to know, is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do. It could scarcely be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations.

I would add that in order to fully understand ourselves, we must know our own past.

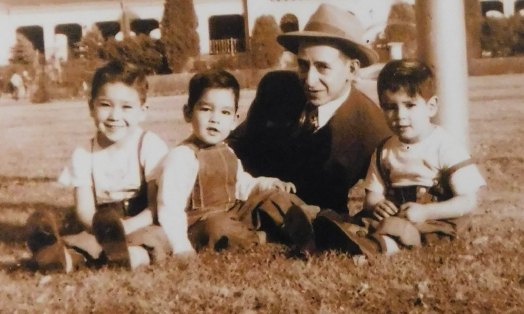

Grandpa Stanley Cody with Nicki, Joey, and Randi Gonzales and Cinnamon, Denver 1990.

My Story

My journey as a historian began in second and third grade, when my mom and dad and Grandpa Stanley bought me my first history books about people like Helen Keller, Abraham Lincoln, Amelia Earhart, Eleanor Roosevelt, Florence Nightingale, and Thomas Edison. In about fourth grade, I discovered an entire series of orange-colored books in my school’s little library. Sitting Bull, Geronimo, Crazy Horse, and Red Cloud—stories of courageous heroes who stood up for their people and showed bravery in the face of danger. These images are still vivid in my mind. At a young age, I was transported to the nineteenth-century American West, before I even knew what the West was.

Some of my best childhood memories were spent listening to my dad and my Grandpa Stanley talk about history. As families are almost always complicated, my Grandpa Stanley wasn’t my biological grandfather. Rather, he was an angel who swooped into my dad’s life at age seventeen, when he tragically lost his mother.

Grandpa Stanley was Polish Canadian by birth. During the Second World War, he served in the Royal Canadian Air Force as a bombardier during the Battle of Britain. One morning, a case of the mumps saved his life: He was grounded while his crew flew their mission and never returned. After the war, he went to Chicago, and then, in the process of moving to California, his car broke down in Denver. Luckily for us, he liked it here.

Sometime in the mid-1960s, he met my dad, becoming a father figure to him. And, years later, he became my Grandpa Stanley. I relished listening to the long, lively conversations they had about the Second World War and how Churchill held on against Hitler. They also talked of Lincoln’s brilliant leadership—long before Doris Kearns Goodwin would write about the genius of Lincoln’s Team of Rivals. I still miss my grandpa and have wondered what he would say about the latest critiques of Lincoln’s leadership in light of his approval of the hanging of thirty-eight Dakota Sioux in 1862 for violence during wartime against white settlers. (Some have pointed out that Lincoln did not follow general military practice at the time, but made a political decision based on the nation’s general racist attitudes toward Indigenous people.)

Of course, my favorite conversations between my grandpa and my dad were those about Bobby Kennedy. “If only Bobby had lived” was an oft-repeated sentiment in our homes. Bobby was a leader of the people. He cared. He understood. My dad taught my sisters and me that Bobby cared about our Mexican American community. He met with Cesar Chavez. I have joked that the Holy Trinity for Mexican American families like mine consisted of Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, and Bobby Kennedy. My dad and grandpa’s message was that we could trust Bobby. Had he lived, they believed that he would have ended the war in Vietnam–where my dad served as a young US Marine in 1967-68. Such moments are seared in my memory—and have surfaced during my time as State Historian, as so many community members have shared their special stories with me.

In grade school, we learned the history of how our nation was formed: The Mayflower, the thirteen colonies, the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and the westward migration. In fourth grade, we learned about Colorado History. I learned about Baby Doe, Horace Tabor, and the Moffat Tunnel. It was also at this time that many of my classmates who came from Italian American families that had moved to Arvada from North Denver began talking a lot about their family stories. They seemed to know so much about their families and about one another.

I wondered about my own history. I asked my parents, especially my mom. Who am I? Where are we from? Where did I fit in in the story of Westward migration? My mom answered these questions with a vague “Nicki, you are American.” I kept asking and putting pieces of our family story together from my Grandpa Gonzales, who came to live with us and who spoke Spanish to his sister on the phone—a language I did not understand—and from conversations with my cousins and great aunts and uncles, who shared information when I asked. As I grew older and put more pieces together, my parents' evasive answers eventually made sense.

My parents grew up in a time—my dad in Globeville and my mom in North Denver and the San Francisco Bay Area, when her dad took a job with Bethlehem Steel–when de facto discrimination and de jure segregation shaped the landscape. My dad remembers that someone put up a sign at the pool in Globeville that said “No Mexicans,” and nobody bothered to take it down. This era reflected Denver’s long history of racist and discriminatory policies and practices restricting access to pools, parks, housing, and other city services to whites only.

Two professors—Jeremy Nemeth, CU-Denver's professor of urban and regional planning and Alessandro Rigolon, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign—have studied Denver’s history and have defined three main periods that added to and together compounded Denver’s history of racism and discrimination.

My grandfather, Louis Gonzales, with my dad, Joseph Gonzales (far right), my uncle Robert Gonzales (middle), and my uncle Manuel Lujan (far left), in Denver’s City Park around 1950.

The first was from 1902-1945, and included the City Beautiful and New Deal eras when policies like redlining dominated, relegating Blacks and Latinos to areas of the city deemed “hazardous” neighborhoods that contained “undesirable elements.” In Denver, these neighborhoods included Baker, Globeville, Highland, and Five Points, as well as others.

The second was the post-World War II era. It was a time of white flight and suburbanization. White people moved away from the city, taking investments and resources with them. Blacks and Latinos remained. Redlining continued, while realtors also steered certain groups away from some areas and into other parts of the city. Preventing racial integration remained the name of the game until 1968, when the Fair Housing Act prohibited discriminatory policies and practices like redlining. This was the world in which my parents came of age.

The third era that Nemeth and Rigolon wrote about is from 1983 to the present—what they’ve termed a time of Urban Renaissance. It is defined by renewal projects like Coors Field, and infrastructure improvements like the light rail. It is an era that began with the election of Denver’s first Latino Mayor, Federico Peña and his call to “Imagine a Great City.” Despite being a “renaissance,” old patterns have persisted. Some scholars have argued that in this time of urban renewal, gentrification is the new redlining, as once again, communities of color are being displaced and relegated to areas deemed less desirable.

Considering this context, I realized that my parents hoped to shield my sisters and me from the pain of the past. They wanted to protect us from a society that treated them as inferior and limited their opportunities because their families were Mexican American. They wanted to make sure that we had opportunities that they did not have. Pervasive racism stole our stories and our sense that we belonged in the larger American story. It robbed us of a fuller understanding of ourselves. But it could not take away our resilience and determination.

Me and my mentor, Professor Victor Luftig, at my graduation from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut in 1992.

Una Carta de Amor

Ironically, it wasn’t until I journeyed east for College that I truly discovered the West and the histories of the people who were my ancestors. Courses at Yale University in the History of the American West introduced me to my own roots. My history professor, Howard Lamar, and my English professor, Victor Luftig, reinforced that my stories and my voice mattered. In our American West course, we read about nineteenth-century Hispanic women who carried more power and authority than their Anglo American counterparts arriving from the East. We read about the diverse mining camps of Southern Colorado, and about a place called Ludlow. I later learned from my great uncle Moises Lujan that my great-grandfather traveled, as an eleven- or twelve-year-old boy, through Ludlow in April 1914. That was the same month as the Ludlow Massacre, when John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s hired police force teamed up with the Colorado Militia and attacked a tent colony of striking miners and their families, leaving at least twenty of them, mostly women and children, dead. Recently, I heard that Professor Lamar, who is now in his nineties and in a nursing home in Connecticut, expressed his delight that he had a hand in my journey to the position of Colorado State Historian. And, Professor Luftig, who happened upon a TV interview I did where I mentioned the role he has played in my journey, said it was a highlight of his year.

When I was in graduate school in Boulder, a Denver attorney named Jeff Goldstein hired me to be the research assistant for a group of lawyers representing the community who had met in that El Rito adobe room in 1980. They were cash-poor Hispano farmers and ranchers. And decades earlier, they had lost their historic land rights to unscrupulous outsiders, a justice system that had refused to recognize their legal documents—some written in Spanish and part of Mexican property customs, and a US treaty with Mexico that had never been honored. My work on the La Sierra land rights case, especially my conversations with plaintiffs like Agatha Medina and Shirley Romero Otero, changed my life and shaped my convictions as an activist historian, who would use the tools of history to tell the stories that had not been told.

As I was completing my PhD dissertation, I was hired to join the faculty of Regis University, where I found my academic home. Regis, a Jesuit university with a mission of social justice and standing with the historically excluded, has always supported my work with students and the larger community. I wake up each day grateful to be able to serve.

As I mentioned, when my appointment as State Historian was announced, love poured in from the Latino community—from leaders of agencies and foundations to community activists and teachers to middle school students who wanted advice on their history projects. A year was not nearly long enough to show my appreciation for their support, so I offer the following, gathered from the stories shared with me. I hope they serve as reminders of where we, as Latinos, have been. And, to our youth, who inherit this historical legacy and will carry it forward in ways that make the rest of us proud, they are reminders of who they are.

Me and my sister, Joey Gonzales (later Kilgour), at my Yale University graduation in New Haven, Connecticut in 1992.

We are spiritual people. Our spirituality is practical. It is tied to the land and defined by a reverence for Mother Earth, expressed through traditions like blessing the fields and gathering healing plants for traditional remedies. This reverence persists in places like San Luis, in the legacy of leaders like Apolinar Rael who spoke frequently about this spiritual connection to the land, “La Sierra le pertenese a Dios y nosotros le pertenesemos la Sierra.” (“The Mountain belongs to God, and we belong to the Mountain.”)

Our churches—mostly Catholic, but not exclusively so—have served as the centers of our communities for generations. It is well known that Black churches in the South and around the nation were both centers of spirituality and of political engagement. Here in Colorado we see similar patterns. Denver parishes like Our Lady of Guadalupe, St. Cajetan’s, and St. Anthony de Padua, and Most Precious Blood in San Luis, served as places of social justice work: offering social programs, immigration legal support, English classes, tutoring for youth, and spaces for political organizing. Priests like Father Jose Maria Lara, Fr. Pete Garcia, and Fr. Pat Valdez served these parishes and became pillars of the community. Fr. Pete, known as being “diplomatically stubborn,” took on the Denver Urban Renewal Authority and the Denver Archbishop, fighting against the displacement of the residents of the Auraria neighborhood in the early 1970s. And it was the Catholic Church’s “Campaign for Human Development”—its version of the War on Poverty—in the 1970s that funded the early years of the Land Rights Council in San Luis.

Spirituality ran deep into other areas as well. I learned of Diana Velazquez, a well-respected curandera—a spiritual healer—who combined her Mexican and Indigenous spiritual practices with mainstream western mental health care practices to create a hybrid approach to mental health care at El Centro de las Familias Clinic—a westside clinic. Today women like Charlene Barrientos Ortiz carry on this tradition, passing on ancestral wisdom to our youth.

We are hard-working people. In “A Worker Reads History,” German poet, Bertolt Brecht, celebrates the laborers who labored to build the grand cities of the world while history exalted only the kings and emperors.

Who built the seven gates of Thebes?

The books are filled with names of kings.

Was it the kings who hauled the craggy blocks of stone?

… In which of Lima's houses,

That city glittering with gold, lived those who built it?

In the evening when the Chinese wall was finished

Where did the masons go? Imperial Rome

Is full of arcs of triumph. Who reared them up?...

Our labor helped build this state. Community members shared family stories of physical labor in heavy industries like railroads, smelters, mining, factories, meatpacking, agriculture, construction, machine shops, as well as restaurants and custodial jobs. It was grueling and honest work that fed our families and provided the framework for our daily lives. During times of war, in particular, we answered our country’s call of duty.

With World War II, our presence grew. About fifteen million Americans migrated from one place to another during the war, and Denver saw a large increase in the Latino population, fueled by economic opportunities brought about by the defense industries; for Denver that was Gates Rubber Company and Remington Arms Plant. In 1940, there were 12,000 Latinos, but by 1960, there were 43,000. Some of this migration came as a result of the 1942 Bracero Program—a guest worker agreement between President Franklin Roosevelt and Mexican President Manuel Ávila Camacho. Between 1942-64, an estimated five million bracero laborers emigrated to the US to fill the mostly agricultural jobs needed during the war. Many worked the sugar beet fields in Northern Colorado. Many braceros stayed beyond their labor contracts, adding to the diversity of cultures within the larger Latino community.

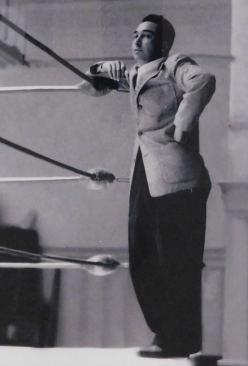

My grandfather, boxing coach Albert Marck, in San Francisco in the late 1950s.

We are shaped by our kinship ties and commitment to community. As I listened to our stories of kinship and community, I recalled what Jesuit priest Greg Boyle has written:

What we’ve come to see as a community is that no kinship, no peace; no kinship, no justice; no kinship, no equality…No matter how singularly focused we may well be on those worthy goals, things can’t happen unless there is some undergirding sense that we belong to each other. How can we stand against forgetting that?

Indeed, we need one another, and we always have. Our long history of mutualistas, or mutual aid societies, reflects our reliance on one another for survival during challenging times and has shaped our cultures, especially in rural areas of our state, where community was a lifeline. Since the early 1900s, in places like Antonito and Chama and later in Denver, the Sociedad Protección Mutualista De Trabajadores Unidos (Society for the Mutual Protection of Workers) provided a menu of supports for workers and their family members, while also serving as gathering places for recreation and community building.

Our rich history of labor union organizing is yet another expression of collective action—often across racial and ethnic lines—for the common good. For generations, our union laborers have fought for just wages and humane conditions for working people. My own grandfather was a proud member of the Meatpacking Union in one of Denver’s meatpacking houses, along with Denver City Councilwoman Amanda Sandoval’s grandfather. Both believed in the dignity of the working class and both passed those values on to their descendents.

Certain sports became very popular among Latino youth and offered safe spaces to come together in community, often forming bonds of kinship. Boxing clubs provided an arena where young boys could learn discipline and gain experience outside their neighborhoods, some traveling out of state to boxing matches. Beloved coaches and individuals made names for themselves in the ring, like Crusade for Justice founder Corky Gonzales. Girls and women, too, played sports, which served as a space of racial and ethnic integration, where they formed friendships and learned the value of teamwork in a society that still saw them as inferior to men. My grandmother, along with her volleyball and softball teammates, challenged the traditional gender norms that were often reinforced at home.

Many community members shared with me stories of evenings spent at the Good Americans Organization. Founded by local leader and Spanish-language radio founder, Paco Sanchez, the GAO was a civic and social organization that often addressed issues important to Mexican Americans and provided a safe gathering space for the community. While both English and Spanish were welcome within the walls of the GAO, its patriotic name reflects larger trends in post-World War II Mexican American history, when societal pressures led many to believe that assimilation offered the best defense against American racism.

My great grandfather, Pio Marck, owner of Walsenburg Pool Hall in Walsenburg, Colorado. My grandfather is the young boy in the middle of his two brothers.

Despite such experiences with racism, we are a patriotic community. Following World War II, mainstream veterans’ groups excluded Mexican American war veterans and the US Department of Veterans Affairs often denied them medical treatment. Organizations like the American GI Forum arose to offer a space where Mexican American veterans could gather in community and claim their dignity following military service. Today the GI Forum in Colorado, in the spirit of mutual aid that has shaped our history, supports college scholarships for active-duty veterans, and children and grandchildren of veterans. They have also supported my work of recording the oral histories of Chicano Vietnam veterans. Young Chicanos served in disproportionate numbers in Vietnam, including my father, who served as a US Marine in 1967-68. I have sought to understand how this experience shaped my father, who is only now sharing his experiences, and other young Chicanos and their communities.

We are a resilient people shaped by a politics of resistance. The era of Vietnam and Civil Rights and President Johnson’s War on Poverty fueled a visible and deeply-rooted politics of resistance and empowerment that would shape Latino history going forward. Building on decades of resistance already present in Colorado’s Latino communities, our state became a center of Chicano activism in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, as activists took on the inequities that had relegated Mexican Americans to second-class citizenship for generations. Activists protested discrimination in the education system, demanding representation in faculty, leadership, and curriculum. Black and Latino parents sued Denver Public Schools, and in one of the first landmark school desegregation cases in 1973, Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver began busing Chicano and Black students to integrate Denver’s schools. The busing policy lasted until 1995, when the Keyes ruling was rescinded. During the era of busing, many white families moved to the suburbs to escape these integration efforts.

This political resistance permeated other sectors of society as well. Organizations like Denver’s Westside Coalition advocated for local voices in the economic development of westside Chicano neighborhoods, while groups like the Crusade for Justice hosted gatherings like the Chicano Youth Liberation Conference in 1969, where El Plan de Espiritual de Aztlán, a defining Chicano movement document, was first presented. Noting disproportionate numbers of young Mexican Americans drafted to fight in Vietnam, Colorado Chicano activists protested what they deemed a racist war, while others took on issues like land rights in Southern Colorado, as well as farmworkers’ and floral workers’ rights. This tradition of resisting injustice continues today, as Latino-run organizations continue to take on the most pressing issues of the day.

Our political struggles have led to more inclusion, as we have seen more Latinos entering mainstream electoral politics. Today, powerful Latinas like Jamie Torres, Amanda Sandoval, Candy CdeBaca, and Debbie Ortega sit on City Council. They carry our history with them, representing all of their constituents, while bringing their historical and cultural sensibilities and convictions to the table.

We are creative people. When denied mainstream opportunities, we have time and again found ways to create our own opportunities. When banks denied us financing for our businesses, we built business districts like Larimer Street and Santa Fe Drive that nurtured our community with businesses that required less funding, like barber shops, beauty salons, print shops, nightclubs, and restaurants. These would become places where people would gather and share food and stories. They became pillars of our community.

While exclusion from mainstream history books and courses prevented us from learning our history in classrooms, our muralists, sculptors, dancers, musicians, playwrights, actors, poets, and storytellers recorded our history on walls, in wood, on stage, and through musical instruments. Today activists are focused on preserving those works of art—our historical record—for future generations.

My parents, Joseph and Alberta Gonzales in San Francisco, California in the early 2000s.

Lessons from the State Historian

In 1968, American poet Muriel Rukeyser penned a line in her poem “The Speed of Darkness.” “The universe is made of stories, not atoms,” she tells us. My year as State Historian was a universe of its own, and it was full of stories. They were about the blessings of kinship, the strength of communities, and finding generosity in the most unexpected ways and places. I discovered many new things as I collected stories from around the state, and each left a lasting impression.

In September 2021, I was invited to a remembrance for the Irish immigrants and children who were buried in unmarked graves in the pauper section of the Evergreen Cemetery in Leadville. They were miners, railroad workers, domestic servants, and laundresses working hard in a land that was not always hospitable to them because of their accents, their culture, their poverty, and their Catholic faith. Some of those buried were children. We know they endured hardship, as many immigrants still do. We know they tended to their faith lives, founding the Annunciation Church. We know they remained faithful to their Irish roots, as they took up Irish Nationalist causes and formed Irish Civic groups that celebrated and preserved their identity. We know they were tough and fought for what they thought was right. At the ceremony, speakers celebrated the fact that in 1880, Irish miners marched down the main street demanding higher pay and better conditions only to be defeated, like other striking workers during the Gilded Age, in their search for dignified treatment and a fair wage. We heard remarkable stories of individuals like Michael Mooney, who embodied resilience and political savvy and became a strong Irish American labor leader.

This particular event was extra meaningful, as my boys are half Irish; their paternal great-grandparents arrived in Boston during the Great Depression, fleeing poverty in Ireland. It highlighted the richness of the Irish immigration experience and the culture that they formed from the hopes and dreams that brought them to America and the often-harsh realities that awaited them in places like Leadville. There was a spirit of solidarity—as the speakers included Latin American immigrants, union organizers, and Ute leaders. The Irish consulate represented the Irish government’s support for the monument. It was also the last public event that many shared with the late, great Dennis Gallagher, who was in his glory shaking hands and giving out his famous business cards with his name written in italics.

During one of my Friday morning coffee gatherings at the History Colorado Center, retired Denver District Judge Gary Jackson, whose accolades are too numerous to name here, joined us and shared his story. Notably, Judge Jackson founded the Sam Cary Bar Association, the African American bar association in Colorado, in 1971, an organization that still today supports and uplifts African American lawyers. Judge Jackson’s mother, Nancelia Jackson, was one of the early settlers in Harman, arriving in 1926. Harman at the time was a Black neighborhood in what is today North Cherry Creek. African Americans settled there because in segregated Denver, it was one of the few areas of the emerging city—near garbage dumps and an area prone to flooding before Cherry Creek reservoir was constructed—where African Americans were permitted to live. Nancelia still lives in the same house, and you can find interviews online where she shares her memories of her nearly century-long life. Harman was annexed by Denver in 1895, in the wake of the Panic of 1893 and the collapse of the silver industry. It, along with many other towns, especially in Colorado, had been on the verge of bankruptcy. Judge Jackson’s family story offers a critical window into Colorado history—of Jim Crow in the Post-Civil War American West—reflecting the history that Professors Nemeth and Rigolon documented in their research on Denver’s history of racism and discrimination in the city’s design and distribution of services.

As a state, we are reckoning with this racist past in various ways. I’m grateful to be serving, along with Dr.William Wei and other state leaders, on Governor Jared Polis’s Colorado Geographic Naming Advisory Board. The very existence of this advisory board is one of many indications that we are living in extraordinary times. The governor has charged the board with evaluating proposals submitted by the public to rename geographical features in Colorado and to recommend name changes. He will then send them to the National Board of Geographic Names. Recently, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, the first Indigenous person to be appointed to a presidential cabinet position, issued her version of an executive order to swiftly eliminate the offensive word “sq--w” from all 660 geographic features in the US that used the term. Twenty-eight of them were in Colorado, where mountains, creeks, canyons, and hills bore the name. Throughout the process, the board has given preference to Colorado Tribes proposing replacement names, and we recently recommended that the previously named Sq--w Mountain be named after Owl Woman, a prominent Cheyenne peacemaker. The Governor approved the name Mestaa’ėhehe Mountain, the Cheyenne name for Owl Woman.

Another highlight was the effort led by Dr. William Wei, who convened board members, Asian American leaders, Regis professor Dr. Michael Chiang, and college students in an effort to rename “Chinaman Gulch” in Chaffee County. Productive research and conversation culminated in a recommendation to Governor Polis to rename the Gulch “Yan Sing Gulch.” Yan Sing means “resilience in the face of hardship” in Cantonese. This new name reflects a much richer, truer story of 19th century Chinese immigrants coming to Colorado for jobs in mining, only to face racism and eventual exclusion with the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. Yet, they survived and left their mark on Colorado history.

In this post-George Floyd era of reckoning with our racist past, one issue we are hearing a lot about in Colorado is the history of Indigenous boarding schools run by the US government and the Catholic Church. In 2022, the US government issued the first installment of its report on US boarding schools. The investigation found that from 1819 to 1969, the federal Indian boarding school system consisted of 408 federal schools across thirty-seven states or territories, including twenty-one schools in Alaska and seven schools in Hawaii. The investigation identified marked or unmarked burial sites at approximately fifty-three different schools across the school system. As the investigation continues, the department expects the number of identified burial sites to increase.

Conversations are now happening about how to respond to the investigations into Indian residential schools—first in Canada and now in the United States. Colorado is doing its own work on this issue. History Colorado is supporting several Tribes in examining the lands around the Teller School in Grand Junction where they believe children are buried. Throughout all of this work, one thing that has become clear to me is a need to do this work alongside Tribal communities, respectfully, gently, and in ways that account for the historical trauma some of them bear, and which generations of family members carry with them.

This work of examining our collective past is all of our work. It was a privilege to witness the efforts of Coloradans all over our beautiful state lifting up the stories that have all too often been ignored or suppressed.

My mom, Alberta Marck (right), her parents Albert Marck, Grace Marck, and younger sister, Brenda Marck in San Francisco around 1954.

Final Reflections

As I reflect on my year as State Historian, I think about the grassroots historians I met who were dedicating their time and talent to collecting and preserving stories of the past. They reflect our collective hunger to mine our past for a deeper understanding of who we are and how we got here. I also think about the lessons that our histories offer us. As one Chicana activist told me, “We tell our stories to make sense of our lives.” Our histories offer us a window into ourselves and an understanding of the present. Our histories offer us a repository of wisdom from which to draw on, as we encounter life’s challenges. We are not alone. Our histories also teach us that we are resilient and creative and that we have a responsibility to preserve and share them with younger generations.

Finally, I return to the small, windowless adobe building in El Rito, in 1980, where Agatha Medina made her way to the front of the room to sign on as a plaintiff in the Rael v. Taylor lawsuit. Rael v. Taylor was the latest chapter in a century-long struggle for her community to defend their historic land rights. Agatha’s courage shaped history that night. She embodied what writer John Nichols wrote in his novel The Milagro Beanfield War, about a Hispano man in Northern New Mexico who defends his beanfield against outside economic and political interests. In describing the residents of Milagro, John Nichols could have easily been describing the tenacious people in El Rito, Chama, San Pablo, and San Luis:

I was just amazed at the ability, particularly of the elderly Spanish-speaking people, to just persist against all odds…they didn’t have the money…the political power...they didn’t have any power with the courts…they just didn’t give up…It was quite a lesson. Call it the stoic, stolid persistence of a community to sustain its land and its culture, its language, and its customs.

In amplifying Agatha’s story, I call on all of us to amplify and celebrate our own histories—and one another’s—especially those that were stolen and deemed not worthy of inclusion in the broader American story. In her widely-regarded TED Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story,” author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie reminds us that “Stories matter. Many stories matter. Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign, but stories can also be used to empower and to humanize. Stories can break the dignity of a people, but stories can also repair that broken dignity.” In reclaiming my own family’s story and sharing it, I honor my ancestors and my community. I empower and restore the dignity of those who came before me.