Story

San Carlos de los Jupes

A Unique Settlement

If you travel on Highway 50 away from the mountains, out into the heart of Pueblo County, you’ll eventually pass a small marker on the side of the road. That sign marks the rough location of a tiny town that existed for only a year, but which represented a unique chapter in the relationship between colonizers and natives.

In the 1780s, Colorado was already a borderlands. It was on the frontier of New Spain, thousands of miles away from the center of colonial government in Mexico City. At the time, New Mexico, Texas, and California were only sparsely settled by Spanish colonists—in fact, there wouldn’t be a permanent colonial presence in Colorado for another sixty years, when the first homesteads were built in the San Luis Valley.

But Colorado was already inhabited. Previously the plains had been the territory of the Apache and the Ute, both of whom clashed with the Spanish forces in New Mexico for generations. Starting in the early 1700s, however, that changed. The Comanches came from the north, from what is now called Wyoming, and displaced other tribes of the area.

The Comanches aso launched raids into Spanish colonial territory, at times as far south as central Mexico, and threatened the Spanish control of las provincias internas, the northernmost and largely unsettled provinces of the Spanish empire in the Americas.

A map of the provinces of Nueva España. The province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México included all of Colorado south of the Arkansas River.

This state of affairs continued for several decades until the late 1770s. In 1779, New Mexican governor Juan Bautista de Anza defeated Comanche leader Cuerno Verde during an expedition deep into today’s Colorado. This was a turning point for relations between the Spanish and the Comanches, in more ways than one.

“What followed not long after the defeat of Cuerno Verde was a pretty bad outbreak of epidemic disease,” explains Dr. Nick Saenz, a professor of history at Adams State University. The Comanches “were kind of forced into a bargaining position. Not long after that, in 1784, a peace treaty was brokered between the Spanish and the Comanche. The [Native American] leader Ecueracapa brokered that arrangement.”

The relationship between Native Americans and colonials remained distant. Though there was an agreement to put an end to raids by either party, the Comanche people did not accept Spanish sovereignty and did not surrender territory. But then, less than a year later, a band of Comanches approached the New Mexican government with an unusual, and surprising, request: they wanted to build a town.

The Comanches were traditionally a nomadic people, traveling freely from place to place, subsisting by hunting buffalo and deer. However, in 1787 Paruanarimuco, the leader of the Jupe band of Comanches, reached out to de Anza’s government requesting that builders and farmers show his people how to develop and live in a permanent settlement.

“It seems like the Comanche may have been interested in the possibility of not having to move around,” explained Dr. Saenz, “and being able to winter in a settled lifestyle.”

Equestrian statue of Juan Bautista de Anza in San Francisco. De Anza had a long and successful career before becoming governor of Santa Fe de Nuevo México.

Judging by the Spanish sources of the time, there may have been some disagreement about how beneficial this proposal would be. But, possibly against orders from his superiors, de Anza eventually agreed.

The Spanish provided workers, tools, farming implements, seed, and livestock to the Comanches. Several dozen New Mexican laborers made the long journey north, more than 150 miles from the settled areas of New Mexico all the way to the Arkansas River, in what is now Pueblo County, Colorado. There, at the confluence of the río Nepestle and the río San Carlos, they constructed a town: San Carlos de los Jupes.

This was a unique moment in history for both the Spanish and Native Americans, in more ways than one.

Notably, the Spanish did not ask for anything in return. This was no small investment, and cost the New Mexican government quite a lot of money, resources, and hours of labor. But de Anza did not ask for goods in return, or concessions. And, most notably according to Dr. Saenz, the Spanish made no attempts to mission at San Carlos de los Jupes. No church or mission was built, and there were no priests, monks, or friars among the men sent north.

This surprisingly generous attitude may be explained by the historical context of the time, and the Spanish attitude towards settlement and resettlement.

“Globally, the Spanish were resettling a lot of people during this period,” explained Dr. Saenz. “In the late 1760s they were settling Catholic Germans in areas of Andalusia which had never been settled before. Around the same time they relocated Canary Islanders to uncolonized areas of Louisiana…and then the Comanche pitched this idea of a new town. From the Spanish perspective, it may not have been a totally outlandish idea. From the government centers in Mexico City and Madrid, who didn’t know about the Comanche or their culture, this might have fit into the same mold.”

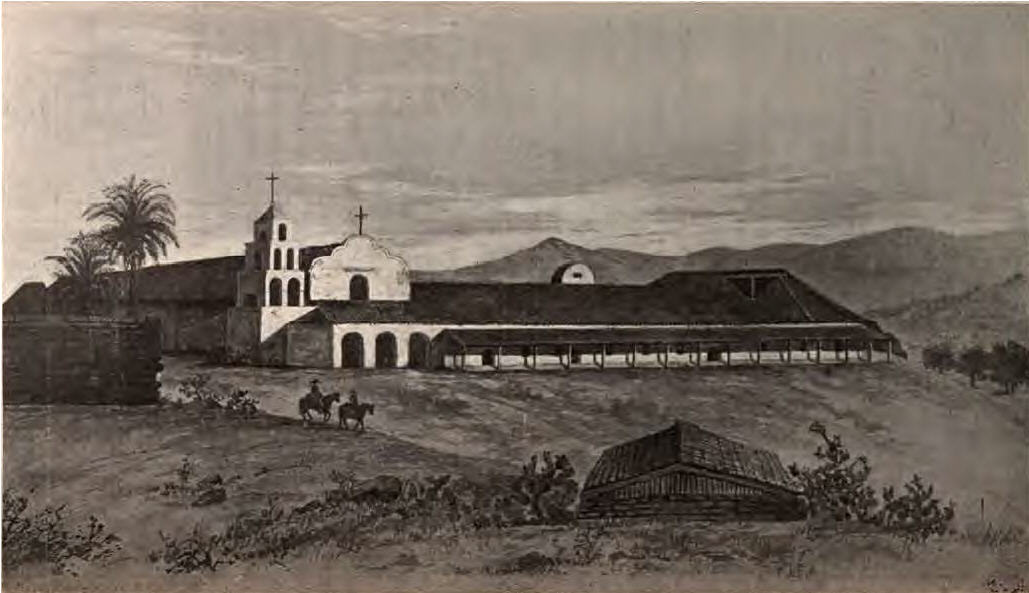

Misión San Diego de Alcalá was the first mission constructed in California, immediately following de Anza's expedition there. The construction of missions like this was the typical way for the Spanish to interact with Native Americans.

However, those attempts were all imposed by the Spanish government, and involved only Europeans who were already familiar with farming. In contrast, the Comanche had approached the Spanish with this idea, not the other way around, and had no prior experience with an agricultural lifestyle.

Dr. Saenz also compares San Carlos de los Jupes with contemporary settlements in Alta California, but that presents similar problems.

“During the 1760s, [the Spanish] built missions in California in the hope that they would bring the indigenous populations into the area to farm, and to develop an urban area,” explained Dr. Saenz. “But what was going on at the Arkansas with the Jupes didn’t have that level of government oversight, and the documents don’t point towards creating some sort of long-term arrangement.”

It really does seem that San Carlos de los Jupes was a completely unique experiment, without any real equivalents anywhere else in American or Spanish history.

“Later developments by the Mexican government or the United States government were not the same,” emphasized Dr. Saenz. “This often struck me as a sort of unique moment. Reservations were marked by clear power structures, a system being imposed on natives. Whereas [San Carlos de los Jupes] is more of a meeting of equals, an attempt to reach some kind of agreement between two communities that, in some ways, saw themselves as the same.”

Unfortunately, the settlement did not last long.

The first sign of trouble came when de Anza was removed from governorship in October of 1787. In his later years he was held in high regard by the indigenous peoples of the region, and much of the arrangement between the Jupe Comanches and the New Mexican government was likely based on the personal trust and respect between Paruanarimuco and de Anza.

When the Comanches learned that de Anza had been removed from governorship, Paruanarimuco attempted to return the tools being used at San Carlos, apparently for fear that without de Anza’s oversight the agreement was now over. The new governor went to great lengths to convince him otherwise, and construction continued.

By that point a majority of the houses for the town had been completed, but in the end it meant little. Only a few months later, in January of 1788, the town was completely abandoned.

In traditional Comanche culture it was considered taboo to make camp in a place where someone had died. And so when the wife of Paruanarimuco passed away in the winter of 1787–88, the band left the settlement and never returned.

Notably, the Spanish did not settle in San Carlos de los Jupes. Although it was discussed by the colonial administration in Santa Fe, ultimately they never moved north into Comanche land or claimed the settlement despite the significant investment they had made into it. And so that unique town, built on an unusual agreement between former enemies, quietly passed from memory. In modern times, there’s nothing left of San Carlos de los Jupes. Nobody is even sure of its exact location. The río San Carlos, now known as the St. Charles River, and the río Nepestle, now known as the Arkansas River, have changed courses multiple times over the last two and a half centuries.

The río San Carlos, now known as the St. Charles River, photographed 1890 by L.D. Regnier. Like the Arkansas river, the St. Charles has changed its course many, many times since the 1780s.

But the legacy of the town, or rather what it represented, was carried on by the successors of both de Anza and Paruanarimuco. In the decades following the signing of the peace treaty, the region began to thrive for the first time in centuries.

“It’s symptomatic of this new turn in Spanish-Comanche relations,” explained Dr. Saenz. “New Mexico starts to thrive. The economy expands rapidly, and a big part of that is the peace with the Comanche. There is a new working agreement, a paradigm shift, between the [Native Americans] and the Spanish.”

The attempted settlement at San Carlos de los Jupes was not the cause of this peace and prosperity, but it was an example of it. And, if nothing else, it is a unique chapter in the long and complex history of relations between the Native Americans and the colonial powers.

Sources:

John, Elizabeth A.H. Storms Brewed in Other Men’s Worlds: The Confrontation of Indians, Spanish, and French in the Southwest, 1540-1795. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

Thomas, Alfred B. “San Carlos: A Comanche Pueblo on the Arkansas River, 1787.” The Colorado Magazine 6, no. 3 (1929): 79-91.