Story

Christmas 1854: The Tragedy that Ended El Pueblo

In the Arkansas Valley of the early 1850s, Ute leaders had a policy of peace, justice, and trade with settlers. But those years after the Mexican-American War brought broken promises from the US government and shifting alliances all around. The resulting violence of Christmas 1854 has long been deemed a massacre.

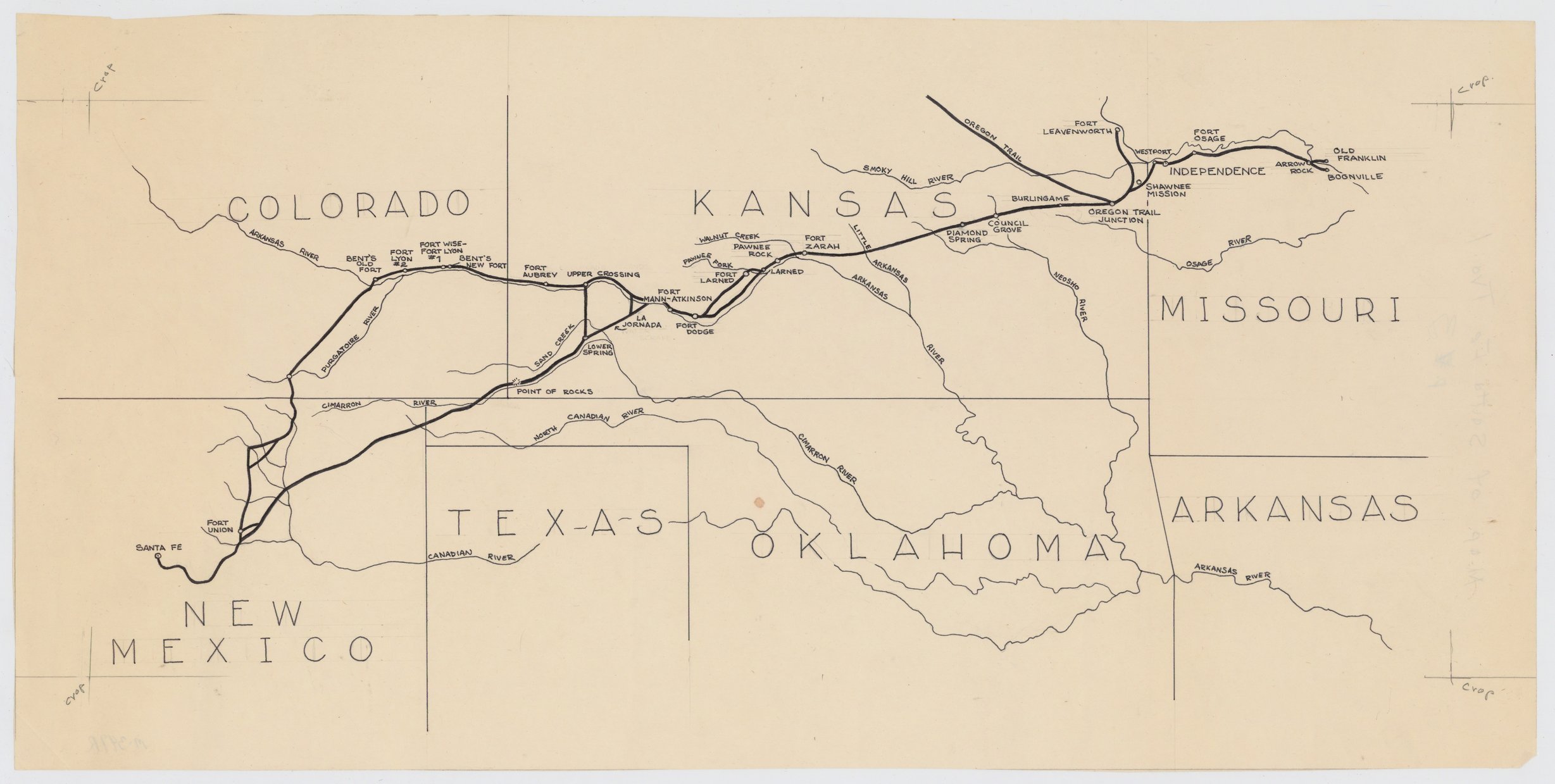

The Arkansas River Valley was one of the first areas of Colorado to be settled by colonists and for good reasons. The area was not far from the established Santa Fe Trail, and also near enough to the mountains to take advantage of the fur trapping trade. The soil was fertile, the summers sunny, the winters mild. By the early 1850s, there were two trading posts along its banks and the beginnings of villages along the river and its tributaries. But Christmas of 1854 changed all of that and led to the area being practically abandoned overnight.

After the attack on El Pueblo trading post that fateful morning, the region would be almost uninhabited until the Pikes Peak Gold Rush.

El Pueblo had been constructed in 1842, making it one of the earliest such trading posts in Colorado. In its early years, it enjoyed lucrative business in furs and trapping and did business with traders from the United States, Mexico, and local Native American tribes—including the Utes.

Before the attacks of 1854 and 1855, the Utes had been characterized by the United States government as largely peaceful. Relations with Ute leaders were good for much of the preceding decade. Chico Velasquez and other chiefs had a policy of peace, justice, and trade, which sharply contrasted with the Apaches and Arapahos, who, at the time, were raiding wagon trains frequently and openly.

Early on in the history of El Pueblo and Bent’s Fort, trade with the Utes and other tribes of the area was beneficial for everyone.

“Trade benefits relationships,” said Deborah Espinosa, retired former director of History Colorado’s El Pueblo History Museum. “You’re not going to trade with your enemies, and everyone stood to gain. But in the meantime, the United States was looking at Mexico and things were already starting to change.”

El Pueblo Trading Post was just north and west of the Santa Fe Trail, which was the main trade route between the southwest and the populated centers of the United States. It was located alongside the Arkansas River, about 70 miles away from Bent’s Old Fort.

The presence of Anglo-American and Hispanic settlers in the area, which only increased following the Mexican-American War and the annexation of the New Mexico territory by the United States, caused significant changes that endangered the Utes’ way of life and even their survival.

Other Plains Indian tribes became more aggressive during the 1840s and ’50s. Many of them had been armed by the United States government during the war, but the Utes were not among them.

“Some tribes were given guns, but the Utes were not,” said Espinosa. “So how were they supposed to protect themselves? How were they supposed to hunt?”

David Meriwether (1800-1893) came from a family of politicians. He spent most of his political career as a member of the House of Representatives for his home state of Kentucky, but he also served as the governor of the New Mexico Territory from 1853 to 1855.

In the early 1850s, Chico Velasquez and other Ute chiefs met several times with David Meriwether, who was the governor of the New Mexico Territory (which at the time included much of Colorado). By all accounts the meetings went well, and Meriwether spoke highly of the Utes for most of his career, but the results were less than ideal.

When the Utes asked for firearms, they were refused outright. When Chico Velasquez asked instead for food, recognition of their ancestral territory, and protection from Arapaho raids, Governor Meriwether promised to provide all of that. But when the time came, the new Fort Massachusetts was built many miles away from Ute territory. Settlers were permitted and even encouraged to build homesteads along the Arkansas and in the San Luis Valley. And the promised food and medicine never came at all.

Following their last conference in the summer of 1854, all of those chiefs who met with Governor Meriwether became sick with smallpox on their journey back to their lands, and they died. Worse still, this spread the disease among their people and led to many more deaths.

This was the last straw for many of the Utes. While it is extremely unlikely that Governor Meriwether purposefully infected the Ute leaders, many of their people suspected that the disease was spread to them intentionally. They were frightened and furious, and with most of the old peace-minded chiefs now dead, new leaders rose to prominence.

“When things become so dire, when it came to such circumstances, it was necessary that a warrior emerged,” said Espinosa. “And that was Tierra Blanco.”

The Utes were desperate and suffering. They had been promised much and given almost nothing, and now sickness and starvation were ravaging their people. Tierra Blanco and his followers lashed out against those who were inhabiting ancestral Ute territory.

“Unfair treatment eventually culminated into hatred,” explained Charlene Garcia-Simms, the president of Genealogical Society of Hispanic America. “Multiple factors led to rising tensions.”

In late autumn of 1854, the atmosphere of the Arkansas River valley grew tense. There were reports of stolen cattle and signs of a large force scouting the area. One woman reported being chased by Ute warriors on horseback, and a trader was found killed, his body abandoned on the banks of Apache Creek.

Buffalo Chase over Prairie Bluffs (1832), oil on canvas by George Catlin. Most plains tribes, including the Ute, were nomadic hunter-gatherers who depended upon buffalo herds for food. Their traditional way of life was incompatible in many ways with colonial settlement.

Early on the morning of December 24, 1854, a group of Ute people arrived at the homestead of Marcelino Baca, a longtime resident of the valley who had lived for a while at El Pueblo. Tierra Blanco was leading them, and he approached the main house apparently peacefully. But one of Baca’s workers, an elderly man named José Barela, realized something was amiss. He recognized that some of the Utes were riding Baca’s horses, which they must have stolen from paddocks before coming to the house. He warned Baca not to let Blanco approach.

Baca shouldered his rifle and warned Blanco to leave. The Ute did so, riding off without another word exchanged, but they stole all of Baca’s horses.

Baca sent a rider to warn the other homesteads and villages along the Arkansas and Huerfano rivers, but realized it was far too late to warn the trading post. He and his workers remained in the main house, where they could hear the distant sounds of gunfire and shouting, for the remainder of the morning. Finally, approaching midday, they felt it was safe to leave and investigate.

When they arrived at El Pueblo, they found everyone dead or missing. Six bodies were accounted for, including that of Benito Sandoval, the comandante of the trading post; two bodies were never found. There were additionally the bodies of five Ute warriors left behind by the attackers.

There were two survivors of the attack, who managed to relay some of what happened to Baca’s group. Juan Rafael Medina was found dying some distance away from El Pueblo, and Rumaldo Córdova was found unconscious near the front gate with an arrow through his mouth. Medina only managed to give a brief account before succumbing to his wounds, while Córdova was forced to give his story using the traditional Plains Indian sign language. He, too, would die several weeks later, presumably from infected wounds.

From Córdova and Medina, Baca’s group learned that Blanco had also approached El Pueblo with feigned friendliness, walking through the front gates and approaching comandante Sandoval to talk. But then he seized the comandante’s gun from his hands and shot him, taking the post’s inhabitants by surprise.

The attack was swift and over quickly. The Ute killed every man in the fort, and took the only woman (Chepita Martín) and children (Felix and Juan Isidro, the young sons of Sandoval) as captives.

Comanche Warrior Lancing an Osage, at Full Speed (1837) oil on canvas by George Catlin. Raids and warfare were carried out between tribes as well as against American or Mexican colonists. During the 1850s, the Ute of central Colorado endured raids from several of their neighbors.

The raid on El Pueblo was the first and largest of the Ute attacks that season, but it was far from the last. Raids and assaults became more and more frequent in the coming months, leading to many more deaths on both sides. The Arkansas River valley soon saw what can only be described as an evacuation as dozens of settlers and their families fled in all directions. Some returned east, others made the dangerous trek to Fort Garland and Fort Massachusetts, others went as far as Santa Fe and Taos. By the end of the year, many of the villages and ranches were entirely abandoned. The only groups to remain were those led by William Bent in his stone fort and Charles Autobees on his Huerfano ranch.

The violence continued for almost a year until peace talks were held at Abiquiú, New Mexico. It was at this meeting that Felix Sandoval was freed as part of negotiations. Through him it was learned that Chepita Martín had been killed only days after the attack, while his younger brother Juan Isidro had been sold as a slave.

Juan Isidro Sandoval was eventually recovered eight years later, for the price of three hundred dollars in silver and a Hawken rifle.

This tragic event and the violence that followed it shaped southern and central Colorado history for years. Settlement in the Arkansas River valley, which had previously been prosperous and steadily growing, was almost nonexistent until the 1859 Pikes Peak Gold Rush. The relationship between the Utes and the settlers was never again as peaceful as it had been.

El Pueblo trading post was completely abandoned from the attack onward, and was never again permanently inhabited. Frontiersmen and travelers would occasionally take refuge in its ruins, but never for long. By the time the modern town of Pueblo was being built, all that remained was the shell of the outer wall, and even that was soon torn down and paved over.

But even as the old El Pueblo vanished, the story of its downfall has remained a part of southern Colorado culture. Unfortunately, in the intervening years many details were added and exaggerations made.

Many later retellings highlighted the fact that it took place during Christmas, perhaps to suggest extra brutality or subterfuge on behalf of the Utes; these accounts also tend to suggest that the settlers were drunk, and sometimes that the Utes were as well. Some even reframe the attack as happenstance, that it began as a drunken disagreement over Christmas dinner. This is all almost certainly incorrect. None of it matches the accounts of witnesses such as the Sandoval brothers, or of those who discovered the site of the attack such as Baca’s party.

Worse still, these accounts diminish or even erase the suffering and conflict that led up to the attack. The attack was premeditated and inspired by years of starvation and rising tension.

“A lot of people call it a massacre,” said Charlene Garcia-Simms. “When our Genealogical Society did a plaque, we called it a tragedy…because it could have been avoided. There were so many broken promises and so many broken treaties. [The Utes] were starving. If the government had kept their word, it could have been prevented.”

Where is the El Pueblo Trading Post?

After the fateful conflict of Christmas, 1854, the El Pueblo trading post was never rebuilt. Some locals salvaged adobe blocks for use in other buildings, while the rest was allowed to melt back into the banks of the Arkansas River. However, the story of El Pueblo was never forgotten and over the years various people guessed its location. Finally, in 1989, Dr. William Buckles, an archaeology professor at CSU-Pueblo, undertook a search for the by then nearly mythological site. Using a variety of techniques including triangulating historic photos, ground-penetrating radar, and good old fashioned digging, Dr. Buckles located the trading fort under the 1882 Fariss Hotel.

Buckles spent twelve years excavating both the Fariss and El Pueblo with an army of volunteers. After his death in the early 2000s, the 110 boxes of artifacts and 20 linear feet of excavation notes from the project was lovingly stored by the City of Pueblo. In 2017 the Office of the State Archaeologist initiated a project to re-analyze and curate the entire collection. To date over 100,000 artifacts have been examined with the help of over twenty volunteers, and student researchers from both Metro State University and CSU-Pueblo.

Sources:

Lecompte, Janet. Pueblo, Hardscrabble, Greenhorn: Society on the High Plains, 1832–1856. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1978.

Garcia-Simms, Charlene. “El Pueblo 1854 Christmas Tragedy.” Pueblo: Fray Angélico Chávez Hispanic Genealogical Society of Southern Colorado, 1998.