Story

James Beckwourth: African Americans in History and the West

There are countless examples of African Americans who left their mark on every stage of history, despite societal and cultural obstacles in the way. However, their stories are often not told or represented either during their lifetime or after. One who defied all constraints of the time and whose name became famous nationwide both during his lifetime and long after his death was James P. Beckwourth.

Jim Beckwourth was a fur trapper, explorer, mountain man, innkeeper, author, storyteller, scout, guide, and more. It is sometimes hard to get a clear picture of the specifics of his life. Even when he was alive in the early decades of the nineteenth century, he was widely considered a teller of tall tales. He was known to his fellow fur trappers and mountain men as a yarn-spinner and avid storyteller, so it can be hard to determine how accurate his memoirs are. But even if only a portion is correct, James Beckwourth was still one of the most impactful, influential, and impressive mountain men of the early days of the American West—which is especially notable given his origins.

James Pierson Beckwourth was born into slavery in Virginia in 1798. His mother was also a slave, and his father was his family’s white owner, who acknowledged James as his son.

“He never let that interfere with his life,” said Edward Wallace, a historical reenactor from New Mexico who has been giving educational performances and presentations as Jim Beckwourth for twelve years.

When Wallace first began his work as a reenactor, he wanted to represent an individual that children of his community could look up to. He chose Jim Beckwourth.

“Jim Beckwourth is definitely a role model,” said Wallace. “He overcame such adversity in his life, and is an example of possibilities. He’s proof that there’s nothing we can’t do with our lives, no matter what our background, no matter our circumstances. He should be a role model for the black community.”

Wallace cited Beckwourth’s many, varied, and great accomplishments as the reasons the trapper should be remembered and recognized.

From his origins as a slave, Jim Beckwourth rose to become one of the most prominent figures of the American West during his lifetime. After being freed by his father, he soon fell in with “Ashley’s Hundred,” an impromptu fur-trapping company founded by William Henry Ashley. This group was composed of about a hundred trappers and mountain men, including some of the most famous, such as William and Milton Sublette, Hugh Glass, Thomas Fitzpatrick, and Jim Bridger. The company would later become well known under a new name: the Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

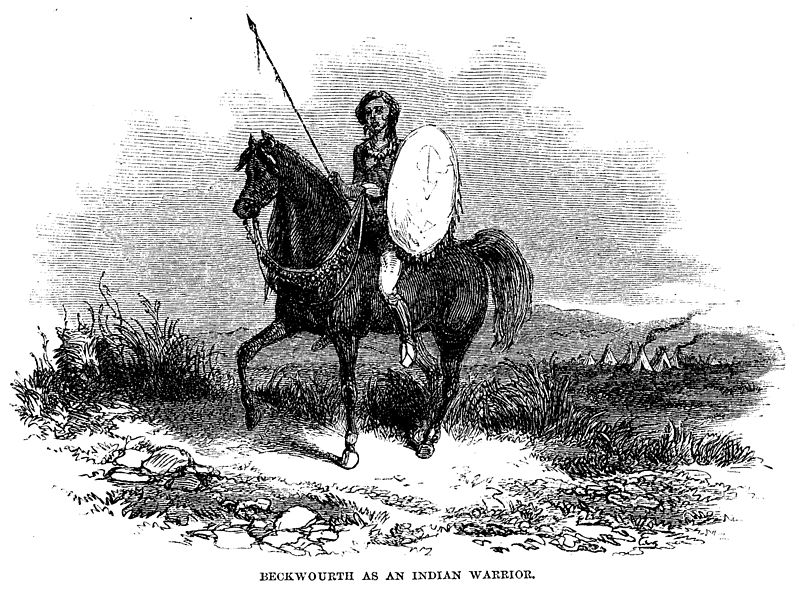

Jim Beckwourth stayed with the Rocky Mountain Fur Company for many years, traveling widely through what is now Montana, Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado. According to his own accounts Beckwourth distinguished himself early on through good relations with indigenous peoples, from whom he learned their methods of hunting, fishing, tracking, and trapping.

His relationship with the Native Americans grew deeper as time went on. Around the mid-1820s, Beckwourth somehow fell in with the Crow nation. He married a Crow woman and lived among the Crow for several years, trapping with them and trading the furs to white traders.

In the mid-1830s Beckwourth left the Crow band permanently. His reason is unclear, though the reason given in his memoirs is a desire to return to “civilization” and a growing weariness with warfare.

This decade-long stay with the Crow nation was by no means the end of Beckwourth’s adventures in the West—not even close. After a brief stint in the army (during which he served in the Seminole Wars), he returned to the Rocky Mountains now as an independent trapper, trader, and guide. It was during this time that he became one of the most noteworthy mountain men of the era, and he was present for and even participated in many of the landmark events in the history of the American West.

“He founded El Pueblo, he owned the most prestigious hotel in Santa Fe,” said Edward Wallace. “He was out west in California during the revolution and the gold rush. He trapped with Kit Carson and Jim Bridger. He lived such a fascinating life to have come from where he was, being born a slave.”

An illustration of Jim Beckwourth dressed in Native American garb, from his memoirs. Beckwourth spent a decade or more living among the Crow Nation in Wyoming and Colorado.

Beckwourth worked at both Fort Vasquez and El Pueblo. He blazed trails across both the Rockies and the Sierra Nevada for westward settlers, and he was present for the Bear Flag Revolt, the short-lived California Republic, the western front of the Mexican-American War, and then the California Gold Rush. He was an army scout with Colonel Chivington’s campaigns against Native Americans in the Colorado Territory, and was a witness to the Sand Creek Massacre.

Throughout his life Beckwourth maintained fast friendships across the nation, in the trading posts of Colorado, the Crow villages all along the Rocky Mountains, the gold fields of California, and the cities of St. Louis and Santa Fe. These friends came from all walks of life and represented almost every ethnicity and race in North America.

Through his skill, capabilities, and personal charisma, Beckwourth overcame the societal boundaries in his way and became highly respected not only among his fellow trappers but even beyond. Later in life he was widely known in stories about the frontier, similar to Kit Carson and Hugh Glass, and was sought out by both the army and westward settlers as a guide and scout.

However, not long after his death in 1866, the perception of Beckwourth began to shift. By this point his memoirs had been widely read for a decade, and they quickly came under attack by historians of the time.

By the 1870s, less than ten years after Beckwourth’s death, historians were calling his memoirs “little more than campfire stories” and using his penchant for exaggeration to dismiss not only his claims but even what he had achieved.

By the time the “Wild West” became cemented in the minds of the American population, Beckwourth had faded from view in favor of other, whiter heroes with equally outlandish tales: Hugh Glass, who fought a grizzly bear and came back from the dead; “Buffalo” Bill Cody, who killed five thousand bison in less than a year; and Davy Crockett, who died fighting at the Alamo and took sixteen Mexican soldiers with him, despite eyewitness accounts to the contrary.

Beckwourth’s story, like those of so many other people of color, was sidelined and dismissed. While it is true that many of the tales in his memoirs were almost certainly exaggerated for entertainment value, there remains a core of truth to them—and there is no excuse for completely dismissing Beckwourth’s very real accomplishments. He achieved as much as, if not more than, his most famous white counterparts. And his contemporaries, the mountain men who traveled and worked with him, clearly greatly respected him for it.

"Buffalo Soldiers", the regiments of African-American soldiers formed following the Civil War, had a major presence in the American West. But like other African-Americans of history, their stories are often under-told.

But because of a combination of his race, his humble origins, and his reputation for tall tales, Beckwourth’s story was ignored or outright rejected, and the truth of it was almost entirely forgotten especially among the general public.

“The fact is that for a long time he was lost to history because of his color,” said Edward Wallace. “In the 1950s, Hollywood made a movie called Broken Arrow, and Beckwourth was one of the characters...but he was played by a white actor.”

The treatment of Beckwourth’s exploits, adventures, and accomplishments, especially in contrast with the ways other mountain men of the time were recognized, only one example of the contributions of African Americans being forgotten or ignored.

“People don’t recognize the contribution of blacks to the American West,” said Edward Wallace. “There were blacks in every aspect of society throughout our history here.”

Despite over a century of relative obscurity, Jim Beckwourth’s accomplishments still live on through storytellers and scholars like Edward Wallace and others. His achievements are being recognized more and more in various museums, including El Pueblo History Museum and Fort Vasquez, as are the accomplishments of other African Americans individuals and communities through history. It is important that these stories are recognized and retold, so that the voices of underprivileged and marginalized groups can be heard—even if it’s centuries after their deaths.

Today, Jim Beckwourth’s memoirs are still in print. They remain an interesting and valuable historical document, providing a detailed and unique source of social history, a look into both Native American and early United States society from the point of view of an individual who, as an African American man and freed slave, was not entirely either.

Sources:

Beckwourth, James P., and Bonner, Thomas D. The life and adventures of James P. Beckwourth, mountaineer, scout, pioneer, and chief of the Crow nation of Indians. New English Edition. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1891.

“James Pierson Beckwourth: African American Mountain Man, Fur Trader, Explorer.” Colorado Virtual Library.