Story

A Big, Complex, and Incomplete Story of the Vote

In the fall of 2018, I started working on plans to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. As we mark this occasion on August 26, what I thought would feel like an ending to this work feels like just the beginning.

The simple stories that we have been told about the women’s vote quickly unspooled and became unwieldy as I travelled throughout the state to talk with people about their local history, looked through archives, and discovered more about the national conversations about the subject. Talking about this history is a balancing act of letting go of the neatly packaged narratives and of being precise because the words used to explain the story can change the impact. It has been a reminder that we are living in a continuing history, not discrete moments in time.

Jillian Allison (second from left) stands with Women's Vote Centennial Commissioners and leaders during the Women's Equality Day March in 2019.

The story of Colorado and the 19th Amendment is often summed up in this way: women got the right to vote in 1920 and Colorado was the first state to enfranchise women using a referendum, or by popular vote, in 1893. These two statements are far too simple and, set side by side, one begins to challenge the other. The 19th Amendment itself is even simpler and less absolute than I had been taught. It states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” Although it’s adoption was the largest expansion of voting rights in our nation’s history, it does not give or guarantee the vote. Practices like poll taxes and literacy tests have been used to disenfranchise Black, Indigenous, and people of color throughout the nation. We also know millions of women could vote before 1920 in Colorado and other states.

Colorado's ratification of the 19th Amendment on Dec. 12, 1919.

Talking about what happened requires some precision to reflect an accurate story but talking about how it happened challenges us to tell a big, complex, and incomplete story. One of the reasons this history is so expansive is because of the circumstances of these pivotal moments of change. Another is the sheer number of people it took over decades to secure the amendment.

It is often said that a “confluence of conditions” led to the women’s vote in Colorado in 1893. This was a second attempt at a referendum. In 1877, one year after becoming a state, Colorado put equal suffrage on the ballot. It failed in every county except Boulder. By 1893 the state had changed. The nation and Colorado in particular was in an economic crisis after the Silver Panic wreaked havoc on the mining industry. During Reconstruction, labor organizations like the Grange sought to build more stability and innovation for their industries. Many allowed for women to fully participate and serve in their offices. Women’s clubs had also formed and the confederation of these clubs allowed for strong grassroots organizing. The Populist Party rose as a formidable third-party alliance that competed with, and in some instances beat out, the Democrats and the Republicans.

In this period of stress and destabilization, suffragists campaigned throughout the state, reaching struggling mining towns, rural farming communities, and cities on whistle stop tours. They wrote for newspapers and convinced many in the press to support their cause—or at least not come out against them. They called on pastors and religious leaders to do the same. As national suffrage leaders like Carrie Chapman Catt toured the state, suffrage organizations formed to convince neighbors, fathers, and brothers to stand with them in solidarity. After securing their own vote, women from Colorado continued to campaign for national women’s suffrage.

Portrait photograph of Carrie Chapmann Catt by Theodore C. Marceau

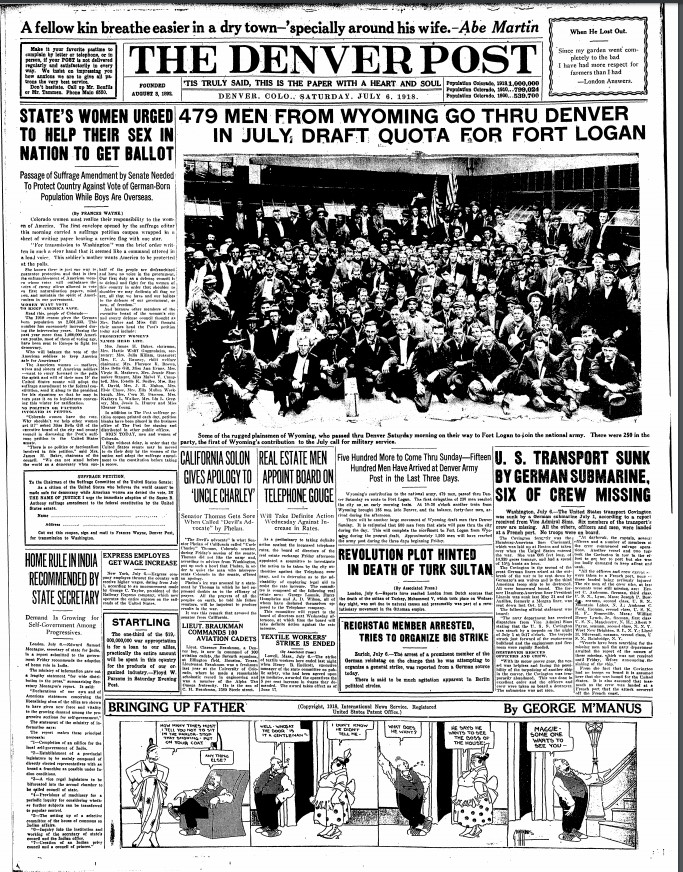

Leading up to the passage of the 19th Amendment, another “confluence of conditions” was building the foundation for change. The United States declared war on Germany in 1917 and the war ended in 1918. Earlier that year, what is now known as the Spanish Flu Pandemic broke out. The 18th Amendment was ratified in January of 1919, beginning Prohibition. The suffragists continued on with their efforts, changing and adapting their tactics as the world and their goals changed. Unlike the suffragists of Colorado in 1893 who appealed directly to the voters, now the larger suffragist movement worked to sway the legislators to adopt a constitutional amendment. In an article published in 1918, The Denver Post called on readers to sign a petition urging the Senate to adopt the amendment, in order to “keep America safe for Americans.” The Women’s City and County’s Defense Council members are listed among the petition supporters. The call claims that women want to “carry forward to the polls in the spirit and will of their men” and “outbalance the vote of enemy aliens.”

This single article in The Denver Post is one example of the complexity of this moment. It demonstrates the intersection of local and Colorado women’s history, the national suffrage campaign and a world war. It raises questions about the role of the press, the changing voting rights of immigrants, anti-German sentiment during the war, organizations that supported women’s suffrage, and the individuals who signed the petition.

In my endeavor to create fitting ways to commemorate this amendment’s milestone, I realized that the history of the vote does not begin and end with women’s suffrage. It is intertwined with the narratives of war, economics, identity, and health because our vote gives us political power within those contexts, as well. The history of the vote is one we are all living. With each new election, a new chapter begins. The candidates, the initiatives, and access to the vote are ever changing—our long, complex, and endlessly fascinating history can help give us tools to understand the process.

Learn more about Colorado and the 19th Amendment at the Center for Colorado Women’s History. Bold Women. Change History. The Exhibition is on display through February 2021.

More from The Colorado Magazine

1904: The Most Corrupt Election in Colorado History Between stuffed ballot boxes, election clerks hopping off trains, and three governors in a day, Devin Flores might just have a point.

“Is America Possible?” The Space Between David Ocelotl Garcia’s and Norman Rockwell’s Freedom of Worship

Doing Our Part Eleven Ways World War II Came to Colorado