Two Hundred Years Ago This Summer, a Member of the Long Expedition Leaves an Account That Melds Science with Adventure

Story

Among the Eternal Snows

Naturalist Edwin James and His 1820 Ascent of Pikes Peak

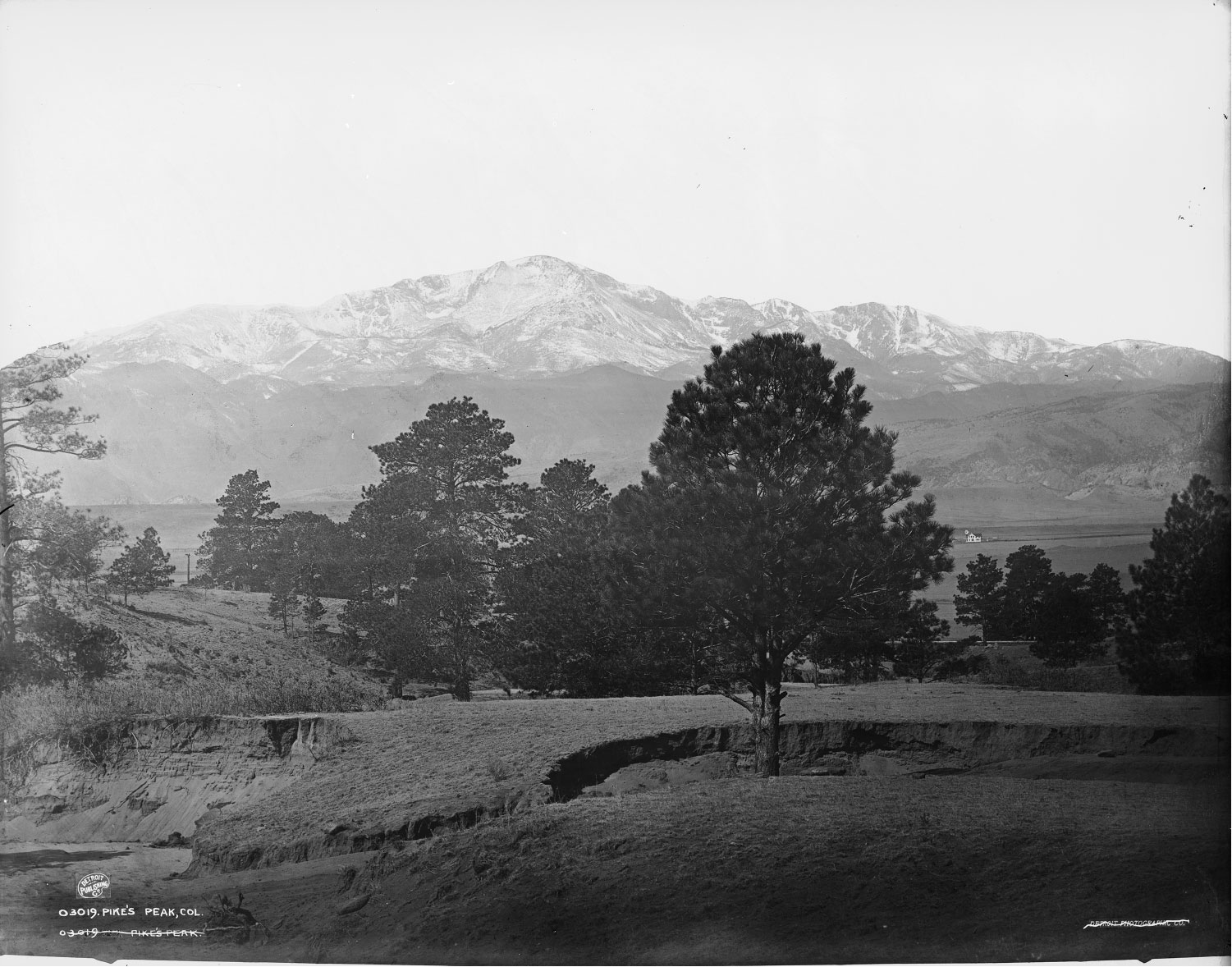

Late in the afternoon on July 14, 1820, 22-year-old naturalist Edwin James and two companions surveyed the world from their perch atop the summit of the “Highest Peak” marked on their map. James scribbled in his journal, which remains unpublished, that “the last part of the ascent was less difficult than I expected to find it . . . .” To the west, he could see two valleys that he correctly surmised held the headwaters of the Arkansas and South Platte rivers. The lesser mountains below him were white with snow from a summer storm. Overhead, amazing him, vast clouds of locusts rode the wind. The men saw no sign of the humans who’d preceded them, only the tracks and bones of bighorn sheep.

The trio stayed but half an hour on the summit as daylight waned, the mountain cast a massive shadow, and the temperature dropped. James had another reason to descend. Below, Major Stephen Long waited impatiently. Long had given James only three days to explore the mountain and return to the expedition’s camp on Fountain Creek. Upon James’s return, the major would head south to the Arkansas and turn east for home.

The Nuuchiu (pronounced New-chew, meaning “the People”), or the Utes, are the longest continuous Indigenous inhabitants of what is now Colorado. According to Nuuchiu oral history, we have no migration story and our people have been here since time immemorial—when they were placed within their homelands, on different mountain peaks, to remain close to their Creator. Nuuchiu Ancestors, in order to maintain transmission of cultural knowledge, taught generations through oral history about the narratives and the names ascribed to geophysical places and geological formations within their aboriginal and ancestral territory.

Pikes Peak is the highest summit of the Southern Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. At 14,115 feet, it is a colossal landform where Mother Earth meets Father Sky. More than a well-known tourist destination, among the Nuuchiu it is a place of reverence. According to the oral history of the Kapuuta (Kah-poo-tah) and Mouache (Mow-ah-ch), two of the twelve historic bands within the Nuuchiu Nation, Pikes Peak is one of the places where the Creator placed their Ancestors.

The Mouache and Kapuuta refer to Pikes Peak as Tava-kaavi (Tah-va-kaav). In the Mouache and Kapuuta vernacular of Colorado River Numic, a dialect of the Uto-Aztecan language family, Tava-kaavi translates as “Sun Mountain.” Pikes Peak was named Sun Mountain because it is the first landform on the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains to greet Grandfather Sun each morning.

Pikes Peak is located in an area where the Mouache and Tabeguache (Tab-e-gwat-ch) territories overlapped. While the Mouache frequented the eastern side, the Tabeguache visited the western side, and the Kapuuta occupied the southern portion during their seasonal rotation to harvest plants and hold ceremonies on the summit.

Tava-kaavi is a traditional cultural property and viewed as an ancestral place of origin to which the Nuuchiu are still connected. Although Edwin James is famous for his ascent in 1820, Nuuchiu Ancestors were the first to summit Tava-kaavi due to their placement by the Creator. To honor the cultural significance of Tava-kaavi, Nuuchiu spiritual practitioners maintain the tradition of visiting the summit and making offerings and prayers at certain times of the year. Although the three Nuuchiu bands were physically removed by force from their ancestral and aboriginal territory, the spiritual significance and teachings pertaining to Tava-kaavi remain within the oral history, prayers, and souls of their descendants—the members of the Southern Ute and Ute Indian Tribe. Tava-kaavi is deeply rooted in our traditional way of life and is a permanent fixture within our identity and lifeways as Nuuchiu.

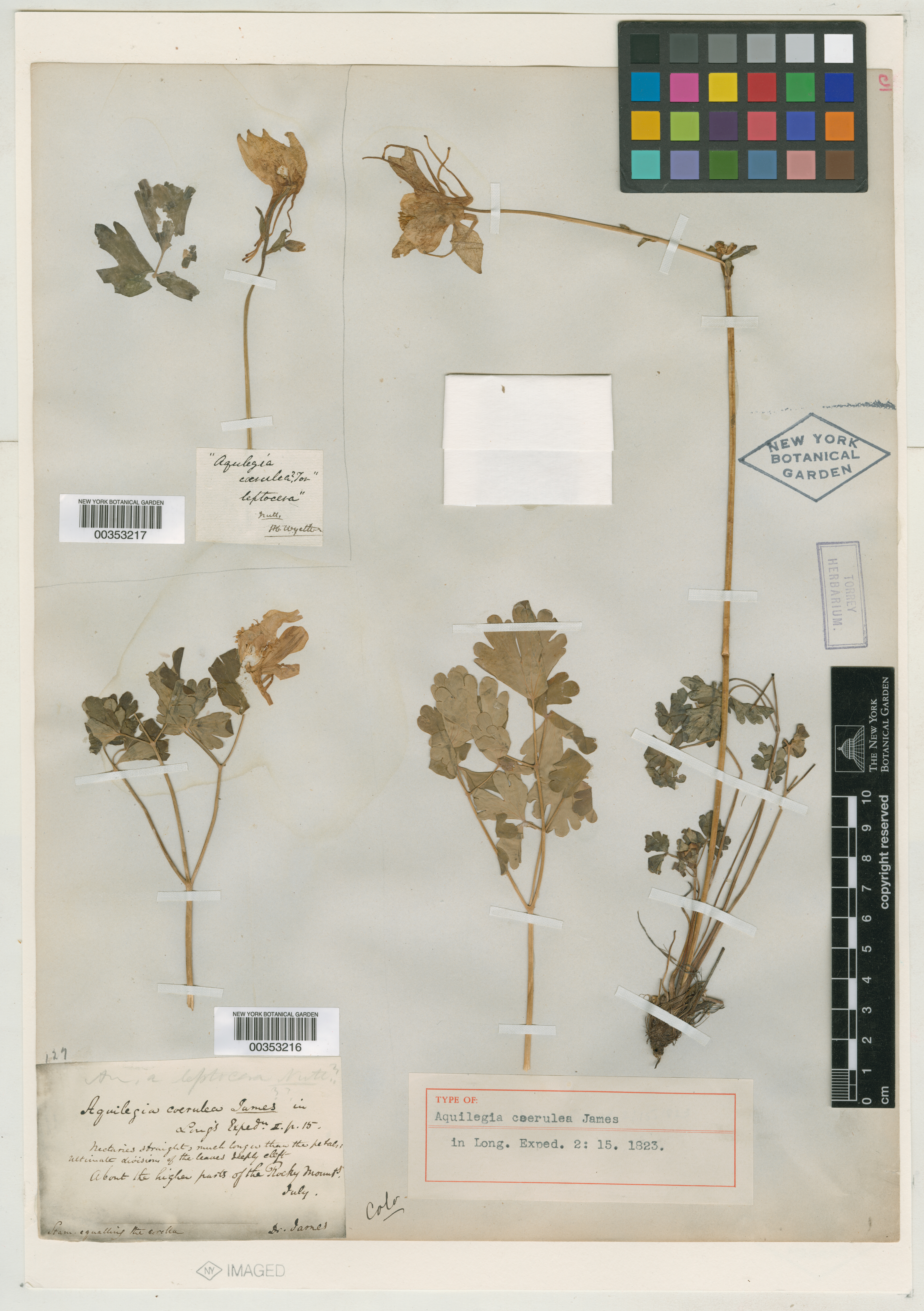

As we look back from a distance of 200 years, unpublished documents in James’s own hand yield still-fresh details about the Long expedition’s lofty goals, its practical accomplishments, and its fraught human dynamics during that long-ago summer. James’s climb stands out not for the ascent itself, but because it combined adventure and science. He returned with the first specimens of previously undocumented alpine flora from the Rocky Mountains. Those who preceded the Long expedition—Lewis and Clark in 1804–06, Pike in 1806–07—did not take scientists (or artists) into the western wilds. And James’s first-hand, summit observations of the sources of the Arkansas and South Platte crucially fulfilled Long’s marching orders and, in the process, improved contemporary maps of the western extent of Louisiana Territory.

In fact, the scientific and artistic work accomplished on Long’s expedition is perhaps the unique contribution of his historically maligned expedition to the Rockies in 1820. Long himself pressured the U.S. War Department to recognize the value of taking scientists on military exploring expeditions. For his 1820 expedition, Long enlisted James as botanist, geologist, and “surgeon” and the respected Thomas Say as zoologist and ethnographer. James and Say’s work contributed to the contemporary maturation of a uniquely American approach to science, independent of its former reliance on European experts.

Long’s superiors grasped that visual renderings conveyed both the wonder and the value of exploring western lands and thus the expedition took two artists: landscape painter Samuel Seymour and assistant naturalist and artist Titian Peale. They returned with the first visual images of this region’s stupendous scenery and unique creatures, marking the birth of western American art, a genre of expression and documentation that stands categorically apart from the region’s Indigenous petroglyphs and pictographs. Even Long’s view of the high plains as a “Great American Desert”—then considered blasphemy to a young, westward-looking nation—may someday seem prophetic.

Today, overreliance on underground aquifers is lowering the water table, climate change accentuates our semi-arid environment, and thirsty Front Range cities snatch up agricultural water rights in the Arkansas and South Platte valleys.

Of course, James’s notion that he might be the first human atop Pikes Peak is, in retrospect, naïve, given more than 12,000 years of habitation in the region. Today, Ute, Pawnee, Kiowa, Arapaho, and Apache elders recount centuries of spiritual connection with Pikes Peak. James merely made the first recorded ascent of Pikes Peak—in fact, the first recorded alpine ascent in North America.

It is unlikely that Spaniards who routinely traversed this region prior to the Long expedition made such an ascent. From the early 1600s to the early 1800s, Spanish hunters, traders, and government expeditions traversed Nuevo Mexico’s northern frontier, at first for imagined riches, then for trade, diplomacy, and war. They named the massif the Sierra del Almagre, but scaling it offered no practical benefit, only danger.

Placed in context, James’s ascent may be seen as an iconic act at a time when written documentation by a scientist was dubbed a “discovery.”

Less than a generation after President Jefferson’s purchase, Louisiana Territory was so vast and poorly mapped that Spain and the United States haggled for a decade over where Louisiana ended and Nuevo Mexico began.

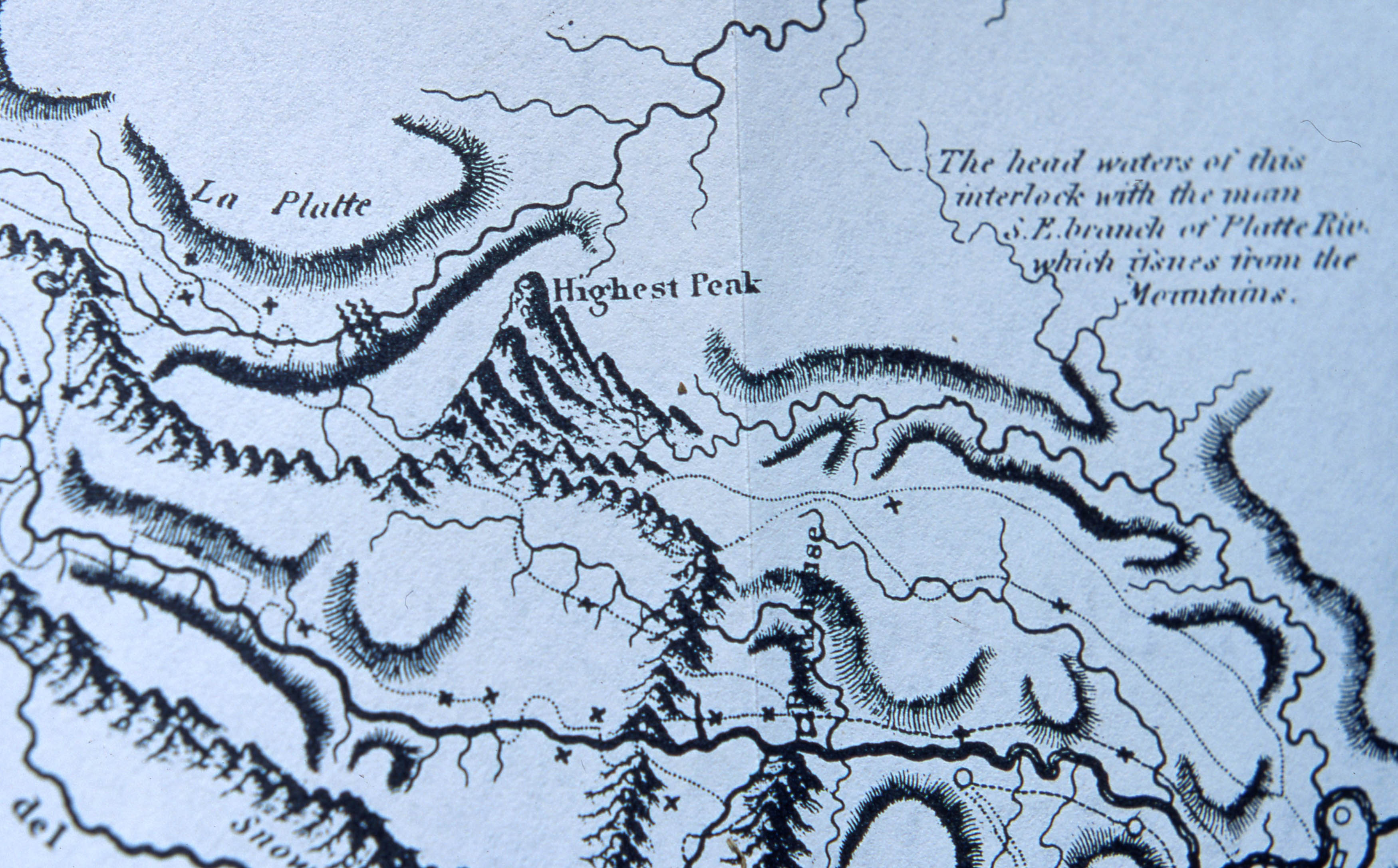

By 1820, European interest in mountaineering had manifested in America. An ascent of New Hampshire’s Mount Washington in 1784 made it “the first American climb to be documented first hand,” writes David Mazel in Pioneering Ascents: The Origins of Climbing in America. Thus the notion that science and adventure might dovetail preceded James. In November 1806, Lieutenant Zebulon Pike had geographic and undoubtedly romantic motivations when he failed to ascend “to the high point of the blue mountain”—the “Highest Peak” in his subsequent report—“to be enabled from its pinical [sic], to lay down the various branches and positions of the country.” Pike’s ascent of a modest foothill southeast of his objective left him certain that “no human being could have ascended to its pinical.” Pike’s 1810 report literally put the iconic mountain on the map: Influential mapmaker John Melish incorporated Pike’s outsized image of it in his highly respected map of America, published in 1816. This image caught James’s eye, and he seems to have understood intuitively that a high Rocky Mountain summit would yield botanical and geological revelations.

Though the War of 1812 had dampened official American interest in exploring beyond the nation’s western frontiers, Long helped revive such interest by leading a cadre of scientists on the ill-fated Yellowstone Expedition to the upper Missouri River in 1819. That expedition sought to stymy British and Canadian traders’ influence with the region’s natives, but it ended as its steamboats struggled in the turbid Missouri and Congress cut its funding. In early 1820, Secretary Calhoun—eager to resume exploration, but strapped for funds—ordered Long to reconnoiter the Platte and Arkansas headwaters in the Rockies. Long had proposed a more ambitious reconnaissance of the Great Lakes, so Calhoun’s orders and paltry funding represented a frustrating setback to his career ambitions.

Nonetheless, Long, a 35-year-old Dartmouth graduate, engineer, West Point instructor, and member of the elite U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, confirmed to Calhoun that he would ascend the Platte and travel south along the Front Range to measure Pike’s “Highest Peak.” The expedition would then split in two, one party to descend the Arkansas, the other to locate and trace the elusive Red River. He would return to civilization by fall.

Philadelphia’s renowned scientific community recommended that Long hire James as botanist, geologist, and “surgeon,” and he did so. James wrote to his brother John, reflecting contemporary prejudice, that he would be taking “a five years’ walk among savages and pagans.” Upon meeting Long in Pittsburgh, James wrote his brother: “I find Long has the appearance of a pretty clever fellow . . . . I believe he has formed a pretty good opinion of me, as to be sure he ought to do.” Three weeks later he wrote his brother again. “I expect to pass my summer most delightfully.” By early May, however, James had learned of Long’s expedited schedule and expressed his own ambitions. “If you will look at Mellish’s [sic] map you will see . . . [near] the source of the Arkansas a peak which is thought to be the highest in the neighborhood. It is our intention to ascend this or whatever other mountain we may find to be the highest . . . . I am sorry to say that we shall make such a hasty business of it. . . . But it is useless to rail. . . .” Yet, rail he did. In one last letter to his brother before departing the Missouri for the mountains, James wrote: “We shall make the greatest possible dispatch for our commanding officer has not the least affection for the service and is in the utmost anxiety to return.” A seed of conflict had taken root.

Long and a gaggle of scientists and soldiers, twenty in all, departed Engineer Cantonment on the Missouri on June 6. All were mounted and armed; none had experience in high plains warfare. Captain John Bell kept an official journal. Lieutenant W. H. Swift served as assistant topographer. James and Say took charge of natural history. Seymour and Peale created a visual record. (Peale’s marksmanship contributed to his duties; contemporary naturalists shot their specimens, then sketched and preserved them.) Various men served as interpreters, baggage handlers, and hunters. They took two dogs, Buck and Caesar. (Both would perish on the plains.)

The topographers took sextants and compasses, and the artists brought notebooks, pencils, pens, ink, and pigments. Provisions included 450 pounds of hard biscuit, 150 pounds of parched corn meal, 150 pounds of salted pork, five gallons of whiskey, and modest amounts of coffee, sugar, and salt—meager stores for a three-month journey. They counted on shooting game. The group also took knives, flints, awls, scissors, mirrors, tobacco, and beads to curry favor with Plains tribes and undercut the influence of British and Canadian frontiersmen.

As the expedition ascended the Platte, Bell led a single column of packhorses and baggage men, flanked by riflemen. The scientists, artists, and hunters fulfilled their duties as they saw fit. Long brought up the rear, keeping an eye on his men and horses. The group rested in camp on Sundays. The expedition encountered in succession the Grand Pawnee nation, the Pawnee Republics, and the Pawnee Loups, who warned that Plains Indians would decimate the tiny group. Long conscripted two French Canadian hunters—Joseph Bijeau and Abraham Ledoux—as guides. Though James early on used the term “savages,” once face-to-face he grew more respectful. Long flew the twenty-three-star American flag and professed friendship.

As they rode up the Platte, the men encountered prairie dogs, rattlesnakes, wolves, wild horses, elk, and “incalculable numbers of Buffaloe.” (In the expedition’s official report, James would suggest a law against slaughtering buffalo, as he came to understand that the herds sustained the Plains’ nomadic peoples.) Violent thunderstorms soaked them. Scorching sun induced brutal headaches and blistered skin. Bell noted that “the dull uninteresting monotony of prairie country” had set in—until June 30. “The mountains are distinctly visible and probably about 60 miles distant,” James scribbled in his journal. “They appear to rise abruptly from the plain and to shoot up to an astonishing altitude.” This mountain would be named “Long’s Peak” by John Fremont twenty-two years later in honor of its “discovery.” The Arapaho people had long known it (and adjacent Mount Meeker) as Neníisótoyóú’u, or “The Two Guides.” Arapaho tradition includes knowledge of the peak’s summit.

To seek Pike’s “Highest Peak” the expedition headed south, “having on our right the range of snow cap’d mountains, on our left an extensive barren prairie, almost as sterile as the deserts of Arabia,” Bell noted. On July 7, Long paused “to give the Scientific gentlemen opportunity of making the necessary investigation for an illustration of the natural history of this new, and heretofore, unexplored region . . . .” Bell observed that, in contrast to his orders, “the Commanding officer does not intend that the party shall proceed to the source of the Platte—but are now to proceed along the base of the mountains to the South [to reach] the Arkansas river, on the way, to examine particularly the high Peake of the Mountains described by Pike . . . .”

Edwin James's specimen of Aquilegia coerulea James from New York Botanical Garden

Three days later, near today’s Air Force Academy, James collected a previously unknown flower later named Aquilegia coerulea James—the blue columbine, declared Colorado’s state flower in 1899. The next day, Bell noted, the expedition crossed “a number of well beaten Indian traces.” This region was hardly the virgin wilderness of American myth. Long encamped just south of present-day Fountain, Colorado. In the expedition’s official report, James later wrote, “As one of the objects of our excursion was to ascertain the elevation of the Peak, it was determined to remain in our present camp for three days, which would afford an opportunity for some of the party to ascend the mountain.” In his journal, which was government property, James diplomatically wrote: “It is certainly to be regretted that a longer time is not allowed us to examine and admire these glorious palaces of nature, but so it is and so let it be.”

But James’s frustrations got the better of him in camp that evening, and the young naturalist confronted his commanding officer. In a post-expedition letter to his brother, he wrote: “I remonstrated, requesting a longer time, but no more could be allowed me.” Quite possibly, the other “Scientific gentlemen” didn’t want to anger Long by appearing to take sides. Perhaps rationalizing, James wrote in his journal that “as we could see large quantities of snow about the upper part of it, and as our guide assured us that the Indians had made many unsuccessful attempts to ascend it I could not perswade [sic] any of the Scientific [members] of our party to accompany me.”

In his journal for July 13, James wrote: “This morning . . . being furnished with provisions and two men to accompany me, I set off to explore a part of the mountains to the N.W. of our encampment, which seemed to be very high and not entirely inaccessible.” Topographer Swift and the guide, Bijeau, accompanied James to the mountain’s base at today’s Manitou Springs to ascertain its elevation. Two riflemen remained with horses for the return ride.

James, rifleman Joseph Verplank, and baggage master Zachariah Wilson began hiking up Ruxton Creek through Englemann Canyon. “At 3 o’clock we commenced ascending the mountain . . .” James scribbled. (Modern climbers will wince at this cavalier start.) “We found it almost impossible to proceed on account of the ruggedness of the ascent and the great quantities of crumbled granite. . . . After laboring over about two miles of this almost impossible tract we laid down to rest for the night, having found few plants . . . to reward us for our toil.”

“This morning we suspended our blankets, provisions and what else we could dispense with . . . and set off at an early hour hoping to arrive at the summit by noon,” James wrote. “After walking about half a mile over the same rugged and difficult road as yesterday we . . . found the way much less difficult and dangerous. At about eleven o’clock we reached the base of the last hill which is steeper and higher than any other in the neighborhood.

“At this place I was not a little surprised to find a change in the character of the rock which . . . I had decided should be granite,” James scribbled. “It contains no mica and has a much evener fracture than most varieties of granite. It continues the same to the summit which we gained at about 2 o’clock p.m. . . . During this day’s excursion [I] found many beautifull [sic] plants wholly unknown to me. The number of unknown plants collected amounts to about 30, many of them confined to the region above that in which I first observed ice and snow.” (James’s journal still bears the outlines of flowers he pressed between its pages.)

“After about 3 hours of laborious climbing we came to the extreme boundary of the timber. Above this the inclination of the surface is greater but the ascent is less difficult, the surface being less obstructed by detached masses of rock. Soon after the entire disappearing of the timber commences a region of astonishing beauty, and of great interest to a Botanist[,] . . . [including areas] . . . closely covered with a thick carpet of short but brilliantly flowering plants . . . .”

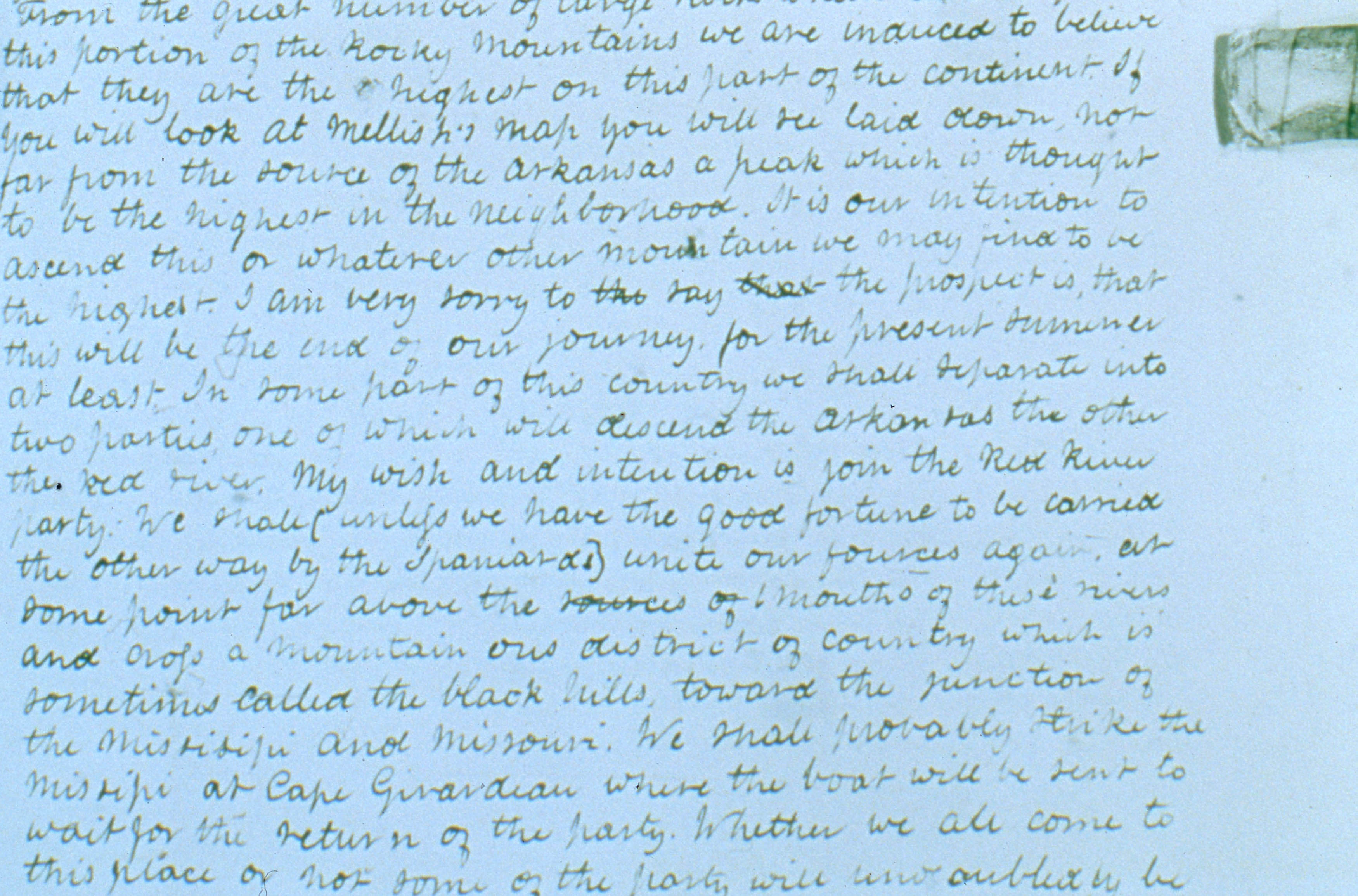

Close-up of James's handwriting in his journal, May 10, 1820.

“At about 2 o’clock p.m. we became so much exhausted with fatigue that we could proceed no farther, and accordingly we halted by a small stream to rest and eat . . . . At this time I thought it would be impossible for us to gain the summit. We were already nearly half a mile above the commencement of the snow, but the top of the Peak was still far distant and the ascent more rapid than ever.

“After a rest of about half an hour we concluded to proceed as though we were convinced that if it was possible for us to reach the summit in that afternoon, it would be wholly beyond our power to return the same night to the place where we had left our baggage. We according[ly] resumed our toilsome march and proceed slowly towards the summit. I found it impossible to go forward rapidly as my attention was constantly occupied by the occurrence of new [plants].”

James’s chronologically challenged narrative ends here. Note that he refers both to resting at 2 p.m. and attaining the summit by 2 p.m. It’s likely they reached the summit at 4 p.m., as he stated later in Long’s official report. As he references the summit early in this passage, James probably wrote much of it on the summit.

James provides a few more details in a testy, post-expedition letter to his brother. On October 26, 1820, he wrote: “With an infinitude of exertion and toil I arrived . . . at the summit of what has been considered the highest peak in this part of the range. The snow extended according to my estimate 1,500 feet down from the summit. This peak had among the french hunters . . . and among the Indians the reputation of being inaccessible. My ascent of it was accordingly thought an Exploit by our party. My want of time deprived me of much pleasure which I should otherwise [have] found in this task.”

In the expedition’s published report, James offered more details on his summit perspective: “The view towards the north, west, and southwest, is diversified with innumerable mountains, all white with snow.” The scene reminded him of his home state of Vermont’s Green Mountains in winter. A summer snowstorm had just preceded them. “Immediately under our feet on the west, lay the narrow valley of the Arkansas, which we could trace running towards the northwest. On the north side of the Peak [stretched] . . . a woodless and apparently fertile valley . . . [which] must undoubtedly contain a considerable branch of the Platte.

To the east lay the great plains, rising as it receded, until, in the distant horizon, it appeared to mingle with the sky . . . .”

Parsing the clues to James’s route in his unpublished journal and published report is tempting but produces only speculation. Based on their start at Manitou Springs, it’s clear that James and his companions began by ascending Ruxton Creek through Englemann Canyon, as does today’s cog railway. It’s also clear that he finished his climb on the rounded shoulder of Satchett Mountain, southeast of the summit, as traced by the cog railway. James’s route between Englemann Canyon and the shoulder of Satchett Mountain remains unknown. If he reached the tiny lake known today as The Crater, southeast of the summit, he would have encountered extensive fields of alpine wildflowers that persist to this day on the north flank of Satchett Mountain. Perhaps that is where he secured his specimens of alpine flora.

One other detail in the expedition’s official report may intrigue mountaineering historians. “We had not been long [on the summit] . . . when we were rejoined by the man [Zachariah Wilson], who had separated from us near the outskirts of the timber. He had turned aside and lain down to rest, and afterwards pursued the ascent by a different route.” I suggest that the only feasible “different route” was a variant on Fred Barr’s early twentieth-century trail up the mountain’s east face.

Mindful of impending nightfall and Long’s deadline, the trio began descending about 5 p.m. and had a few hours to reach timberline and huddle overnight around a campfire. The next day, as they approached their first night’s campsite, they detected smoke then a small forest fire—ignited by the campfire they’d left burning. They rejoined their comrades at present-day Manitou Springs. James wrote later: “A large and much-frequented road passes the springs and enters the mountains, running to the north of the high Peak. It is travelled principally by the bisons, sometimes also by the Indians. . . .” This ancient trail is paralleled today by Route 24 up the aptly named Ute Pass.

The men rode hard for Long’s camp on Fountain Creek, reaching it just before dark. Swift had measured the “Highest Peak” at 11,507 feet elevation—nearly as far under the mountain’s actual elevation of 14,115 feet as Pike’s estimate of 18,581 feet was over it.

Long broke camp at first light and the men rode relentlessly for the Arkansas River, “through a dry barron [sic] country destitute of water herbage and game,” Bell noted. The major camped on the Arkansas for two days to allow James and others to ascend the river, though it was clear they would not reach its source. Two small parties followed an existing “trace” to the formidable barrier of present-day Royal Gorge, where they turned back. James’s perspective from the summit of the “Highest Peak” remained the only information the expedition would gain to fulfill Calhoun’s orders to locate and explore the Arkansas and South Platte headwaters.

On July 19, the expedition descended the Arkansas towards home. Near present-day Pueblo, Long honored James “by nameing the High Peake, ‘James Peak’ believing him to have been the first American that ever ascended to its sumit,” Bell wrote. James’s spirits flagged as he wrote in his journal. “This morning we turned our backs upon the mountains . . . . It is not without a feeling of regret that our only visit to these ‘palaces of nature’ is now at an end. . . . Fifteen hundred miles of drearie [sic] and monotonous ‘prairie-crawling’ in the heat of summer are between us and the ease and comfort of inhabited countries. . . . [The Arkansas valley] is arid and sterile and must forever remain desolate.” This assessment influenced Long’s subsequent map that labeled the high plains the “Great American Desert.” For a westward-facing country soon to embrace a nationalist devotion to “Manifest Destiny” this view earned Long and his expedition two centuries of notoriety.

The rest of the expedition’s travails were many, with James and others infected with tick- or mosquito-borne malaria. Unable to travel, James stayed behind in frontier lodgings. Perhaps this explains his pique at Long, as he expressed in letters to his brother. “You will probably expect in this letter some account of my adventures,” he wrote, but “I am full of complaining and bitterness against Maj. Long on account of the manner in which he has conducted the Expedition and if I cannot rail against him I can say nothing. We have travelled near 2,000 miles through an unexplored and highly interesting country and have returned almost as much strangers to it as before. I have been allowed neither time to examine and collect, or means to transport plants or minerals.”

Having complained, however, James warmed to bragging of his exploits, before plunging again into vitriol. “I have however seen many strange things.

I have moreover seen the Rocky Mountains and shivered among their eternal snows in the middle of July

which every man has not done. I have also lived many weeks without bread or salt, gone hungry for a long time, eaten tainted horse flesh, owls, hawks, prairie dogs and many other uncleanly thing[s]. . . . Maj. Long has left me with 28 doll.s, ragged and destitute, to winter as I can in the western country.”

Despite James’s resentments, he acquiesced in Long’s request that he pen the expedition’s official report, An Account of an Expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains . . . , published in two volumes in 1823.

Today, the sheer volume of natural history work accomplished on the expedition has led to a reevaluation of its place in the history of western exploration. James collected nearly 700 plants, many previously unknown to non-Indigenous science. His friend and fellow naturalist, Say, returned with scientific descriptions of the coyote, the grey wolf, many insects and birds, and extensive ethnographic data. Seymour returned with perhaps 150 sketches, though fewer than two dozen survive. Peale produced more than 120 field sketches and managed to preserve nearly 60 zoological specimens. The two artists had tried to capture the unique grandeur they had witnessed, while embellishing it for eastern audiences.

Long went on to an extensive, useful career as an Army explorer and engineer. James served as an Army surgeon, studied the Indian languages of the Great Lakes, and worked as an editor for the New York State Temperance Society. He retired with his wife and son to a farm on the Mississippi River in present-day Iowa, where he assisted slaves on the Underground Railroad. His niece, Clara Reed Anthony, remembered him as “an eminent scholar, a radical abolishionist [sic] and reformer of great moral rectitude and unflinching courage. . . .”

Long’s gesture bestowing James’s name to the peak never stuck. Colonel Dodge’s 1835 expedition to the Rockies and John Fremont’s subsequent visits in 1843–44 are credited with establishing “Pike’s Peak” as the mountain’s name. The “Pike’s Peak Gold Region” advertised in 1858 guidebooks cemented that name. In 1866 botanist Charles Parry redressed the matter by assigning the name James Peak to a 13,294-foot mountain on the Continental Divide west of Central City. James never knew. He died in 1861, leaving an unpublished expedition journal and ninety highly personal letters as evidence—as if preserved in amber—of his youthful feat and his fierce ambitions in that long-ago summer.

For Further Reading

This article is based on two sets of unpublished documents in Edwin James’s own hand. James’s expedition diary, “Notes of a part of the Exp.n of Discovery Commanded by S. H. Long, Maj., U.S., Eng etc etc 1820 . . .,” resides in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University’s Butler Library. The “James Letters” to his brother reside in the Western Americana Collection at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Two secondary sources offer diverse insights into the Long expedition: George J. Goodman and Cheryl A. Lawson’s Retracing Major Stephen H. Long’s Expedition: The Itinerary and Botany (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995) provides the best analysis of its route (minus the Pikes Peak climb) and botanical work; Kenneth Haltman’s Looking Close and Seeing Far: Samuel Seymour, Titian Ramsay Peale, and the Art of the Long Expedition, 1818–1823 (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008) documents the crucial role of visual art in western exploration and analyzes Seymour and Peale’s output as a romantic blend of documentation and fiction.

More from The Colorado Magazine

Were They Mexicans or Coloradans? Constructing Race and Identity at the Colorado–New Mexico Border Emerging Historians Award

Colorado Is My Classroom More than a century ago, open-air classrooms had a moment in response to another pandemic. Then it was tuberculosis, another era-defining airborne pathogen that attacked the respiratory system. And the results were encouraging. Could fresh air be part of the solution to school in the time of coronavirus?

Vision and Visibility Kathryn Redhorse, director of the Colorado Commission on Indian Affairs, reflects on 2020 as a potential turning point in American Indian and Alaska Native communities’ long struggle for visibility, acknowledgment, and social justice.