Story

Bright Spot

In this excerpt from Becoming Colorado: The Centennial State in 100 Objects, historian William Wei shines a light on the popular holiday decoration.

Denver has its share of urban legends. One story handed down for more than a century is that Denver is the place where the custom of putting up outdoor holiday light displays, especially stringing Christmas lights on outdoor trees, got started. According to this often-told tale, in 1914, David Dwight “D. D.” Sturgeon, a local electrician, wanted to bring some Christmas cheer to his bedridden son. He conceived the idea of connecting lightbulbs that had been dipped in red and green paint to a strand of electrical wire and then wrapping the wire around a pine tree outside his son’s window. The colorful display soon attracted Sturgeon’s neighbors and many other people who came from afar to see this novelty themselves.

This is a marvelous story, one that resonates with the popular holiday film It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). It is easy to imagine the beloved actor Jimmy Stewart portraying “D. D.” Sturgeon, coming up with the idea, and then clambering up the pine tree to literally and figuratively brighten his sick son’s day. Without intending to, Stewart/Sturgeon starts a new holiday tradition that is embellished over the years and practiced by countless others around the world.

The story was popularized after local city boosters such as Denver Post reporter Pinky Wayne began to promote Sturgeon’s tree as the country’s first illuminated outdoor Christmas tree. As the popularity of outdoor holiday lights took off nationally, Sturgeon was dubbed the “Father of Yule Lighting.” His thoughtful act inspired others across the country to emulate him, and soon, dark winter nights in Denver and across the country were lit up with electric Christmas decorations, spreading holiday cheer. Things did not stop there. According to local historian Rosemary Fetter, the widespread use of outdoor Christmas lights gave rise to flashing electric billboards and even today’s neon signs.

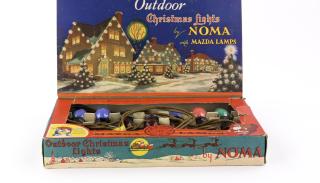

During the Great Depression, manufacturers came out with comparatively inexpensive all-purpose Christmas lights such as the boxed set pictured here. The “Outdoor Christmas Lights by Noma” could be used for decorating trees inside and outside the home. This particular set consists of a string of seven multicolor bulbs that can be connected to five similar strands of lightbulbs. Before then, ordinary lights as well as Christmas lights for indoor use were expensive. In 1900, a box of eight bulbs cost twelve dollars, which was a month’s pay for many people. At those prices, the celebration of Christmas with colored lights was an upper-class privilege rather than a popular practice.

As the cost of Christmas lights dropped, outdoor displays spread. By 1919, Denver Civic Center’s regular lights were replaced with festive holiday lights for the season. By the 1920s, the city was aglow with so many holiday lights that it proclaimed itself the “Christmas Capital of the World.” By 1938, Denver’s city and county buildings were being decorated with Christmas lights. Since then, Denver has marked the beginning of the holiday season with an annual Grand Illumination celebration, when the downtown area is illuminated with 600,000 lights. In 1975, the city upped the wattage by adding an annual Parade of Lights to its holiday festivities, complete with marching bands and ornate floats. Traditionally, the city’s Christmas lights remain on until the end of the annual National Western Stock Show in January. With its buildings and parks festooned with LED magic, Denver has earned the well-deserved reputation of a city that knows how to light up the winter holidays.

You can see this object—and 99 others that helped shape the Centennial State—in Zoom In at the History Colorado Center in Denver. Copies of Becoming Colorado are available for purchase here.