Story

Long Life

Long’s Gardens, a Centennial Farm, has persevered over the years by adapting its practices and products to be environmentally conscious. Here’s how they did it.

Six months isn’t a long time—unless you’re told by a doctor that that’s all the time you have left. That’s what happened to Jesse Dillman “J.D.” Long when he was diagnosed with tuberculosis in the late nineteenth century. At the time, and before the discovery of antibiotics, the recommended treatments were varied, from using cod liver oil to vinegar massages and inhaling hemlock or turpentine. Some said that a dry, arid climate could also help. So Long, like many others with similar diagnoses, decided to head west.

He traveled to Idaho before making his way to Colorado Springs in 1900. Six months came and went, and when Long’s tuberculosis improved, he moved to Boulder and bought Noah’s Ark Store in 1905. The general store had an established seed catalog for fruits, vegetables, and flowers—and the latter inspired him. In a 1982 article by journalist Carol Kreck, she quoted J.D. Long’s thoughts on being able to grow more flowers: “Sometimes I wonder what would it mean to the people of any community [if all] were to raise two or three times as many flowers as they had grown before?...It’s beyond me to estimate the amount of joy that could thus be given to the sick and many who are not situated so they can grow flowers.”

J.D. Long, shown here with his children, Carleton, Everett, and Elizabeth, walking through a tulip field on the farm around 1920.

The seed store, which had been renamed the J.D. Long Seed Company, made its home in downtown Boulder at the intersection of Fourteenth and Pearl Streets for many years. In 1916, hoping to expand, Long purchased a plot of land a little north of the growing town. He used the lot to propagate seeds and bulbs for the downtown store. By the late 1940s, Long was known for producing gladiolas, peonies, and irises that thrived in Colorado’s climate.

His son, Everett, and daughter-in-law, Anne, took over the farm in the 1940s and Long passed away in 1948, five decades after that grim initial diagnosis. Everett ushered the farm into the machine age with the use of tractors instead of horses. They knew to have a sustainable farm they would need to have a reliable source of water, so they created a dam to store water. The Longs also focused their efforts on plants that could grow well in Colorado.

Gladiolas, which had been a main product for the family business, used too much water to be a long-term viable product. In the 1940s, the Longs began to grow more drought-tolerant irises, which eventually became their specialty because these bulbs do not like soggy ground. Colorado’s arid climate was, luckily, well suited to these plants’ needs.

The decision to focus on irises was timely. In Colorado, drought and water shortages are not uncommon. Water shortages were so severe in the 1970s that Denver city officials were deeply concerned that the supply of drinkable water would run out. Various water-saving measures were employed and city officials who wanted to conserve water without forcing people to sacrifice beautiful plants created Xeriscape, which is the practice of creating landscapes to reduce or eliminate the need for irrigation or excess water.

Xeriscape practices include using native plants, focusing on soil health, and planting low-water groundcover. In the western United States, over half of the drinkable water is used on landscaping efforts; Xeriscape can reduce the amount of drinkable water used in landscaping by sixty percent. Another benefit of Xeriscape is the emphasis on native plantings in landscapes. Plants native to areas with an arid climate are going to survive better since they have been acclimated to the harsh conditions over time.

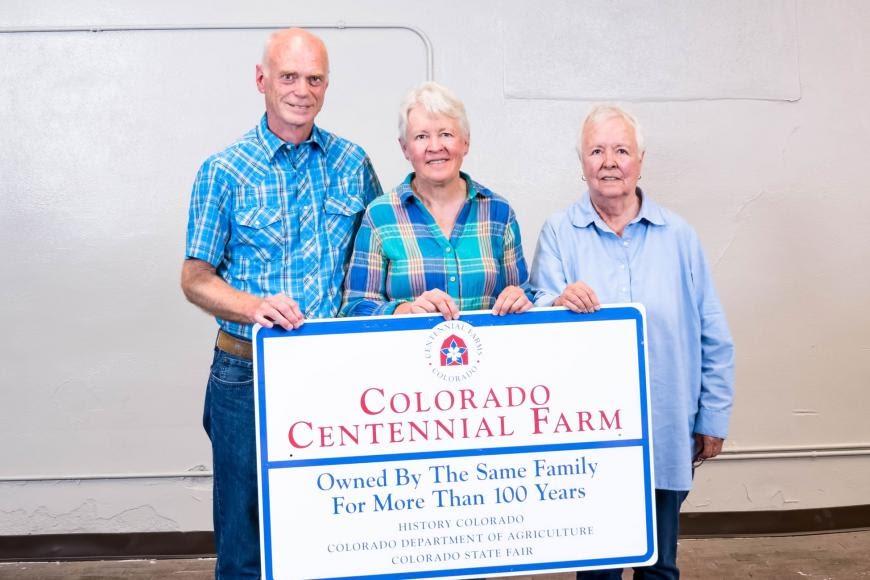

Catherine Long Gates, J.D.’s descendent and current owner of the farm, says that they have worked hard to educate visitors about the drought-tolerant nature of irises and Xeriscape principles. They try to educate others about the benefits of good groundcover and soil health. It is work that has continued for several generations. In 2018, the operation was named a Centennial Farm, a designation given to Colorado farms that have been continuously operated by the same family for 100 years or more.

Over time, Long’s plot, which had been north of Boulder, was engulfed by the city. In the 1950s, the opening of the Boulder-Denver Turnpike made it easier to get to the city, and new employment opportunities with the National Bureau of Standards and the Rocky Flats Plant brought many to the area. During this period, Boulder grew from a city of 25,000 to 37,000, and in the 1960s its population grew to 66,000 residents.

Today, eleven decades after Long started selling seeds—and long after the six months he was given to live—his legacy endures. Long’s family still works to bring beauty and nature to the surrounding community, and it will continue to do so. After a decade of negotiations, the City of Boulder purchased a conservation easement for the property (it was finalized in March 2021). The conservation easement means the property will remain a farm, and Long’s dream of bringing beauty to others will continue.