Story

Shroud, Destruction, and Neglect

As Chicano/a/x murals are erased in Denver, an archaeologist looks at the legacy of these art pieces—and why they need to be preserved.

As an archaeologist, I excavate ancient centers that were abandoned centuries ago. When archaeologists recover monumental art in an abandoned center, the art helps to interpret some of the customs and beliefs of the people that once lived in these sites. In ancient Mesoamerica (present day Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Belize) mural discoveries are significant because they often provide a rare glimpse into how artists visualized their supernatural and natural worlds.

Chicano/a/x* muralists in the late 1960s emulated the Mesoamerican tradition of storytelling and imagery and began to paint murals describing their customs, beliefs, and traditions on the walls of public buildings in historically marginalized neighborhoods of Denver. Interlinking iconography from Mesoamerica and the Indigenous Southwest, contemporary and ancestral figures stood in backdrops of both ancient and modern, urban and rural landscapes from New Mexico, Mexico, and Colorado. The murals were often painted in a social realist style emulating the Mexican mural movement of the early 1900s, with narratives of contemporary and historical individuals and events.

This eclectic art style often portrayed difficult themes of displacement, slavery, and socioeconomic inequality, while at the same time visualizing the present and a better, equitable future. Muralists displayed the importance of protecting our environment and the prominent role of women in our communities, while celebrating the ethnic diversity in Colorado and the nation. Muralists created art for the disenfranchised, striving to kindle a cultural reawakening and a sense of pride in Black, Indigenous, Asian, and Latino communities.

Learning From the Past, Focused on the Future by Andy Mendoza and Linda Clemente, 1151 Osage Street, 1994.

A distinct mural aesthetic developed in Colorado in the late 1960s, as bold, vibrant colors and imagery began to appear in public spaces. The murals described histories and contributions of people of color that filled a void found in cultural museums and education curriculum that failed to acknowledge their presence throughout the city, state, and nation. The images on these murals helped to replant ancestral roots and heal open wounds after centuries of cultural abasement. The murals greeted children when walking to school, observed community events, and often embraced individuals during moments of grief or happiness.

Unfortunately, from the birth of the mural movement, these images have continually been under threat and often erased from our communities by outside forces due to gentrification, displacement, and devaluing the art in Denver. Despite decades of social justice activism in the state combatting socioeconomic inequality, many communities of color continue to experience extreme displacement and cultural erasure as Denver races to be a regional cosmopolitan center, sometimes seeming to aspire to become the most gentrified city in the country. To examine these issues more closely, we will look at the events and art pieces that triggered the mural movement in two Denver neighborhoods—the Westside and the Northside—which are both experiencing extreme gentrification today.

Many families that live and once lived in these communities can trace their ancestry to the late 1500s and 1600s in the American Southwest. Of both American Indian and European ancestry (largely Spanish), Hispanos lived for hundreds of years in, primarily, New Mexico and later in southern Colorado before the land became part of the United States. Hispanos formed a distinct lifestyle, Spanish dialect, and architectural and artistic style in the northernmost frontier of the Spanish Empire.

As I observed in a piece I wrote in 2019, “From the initial exploration of Coronado in 1540 to the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, from the fight for Mexican independence in 1810 to the annexation by the United States in 1848, southwestern communities witnessed intense cultural clashes and changes to their daily existence.” During one lifetime, some individuals lived in the Spanish Empire, then Mexico, then the United States. These drastic changes, and the loss of land rights due to broken treaties after the annexation of the Southwest from Mexico, prompted migration from New Mexico and today’s southern Colorado to Denver and other regions of Colorado.

A close-up of Learning From the Past, Focused on the Future by Andy Mendoza and Linda Clemente, 1151 Osage Street, 1994.

Along the South Platte and Cherry Creek Rivers, various Tribes, including the Ute, Comanche, Arapaho, and Cheyenne peoples, lived in seasonal encampments. In the mural by Andy Mendoza and Linda Clemente, painted in 1994 on 1175 Osage Street in the La Alma neighborhood, the artists depict the discovery of gold in 1858 in a tributary of the South Platte River. The artists describe how European immigrants from the East Coast and the South—along with many displaced Hispano and Mexican American families—began to settle along the riverbanks, quickly transforming this vital Indigenous migratory route into the towns of Auraria and Denver. Immigrants worked in the nearby railroad and the rapidly growing manufacturing industries. One of the early settlers, Alexander Cameron Hunt, homesteaded what became Lincoln Park, a gathering place for the Auraria neighborhood.

The Auraria neighborhood became home to a working-class population, small business, and industry with a large concentration of Hispanos and Mexican Americans by the late 1930s. One of these families, Ramon and Carolina Gonzalez, moved into the neighborhood in the early 1920s. In 1946, the Gonzalez family transformed their home at 1020 Ninth Street into the Casa Mayan Mexican restaurant and cultural center where the family hosted events celebrating their heritage with food, music, dance, and theatre performances.

The neighborhood was one of thirteen redlined on the City of Denver map in the 1940s to delineate cultural minority neighborhoods. The red lines around neighborhoods helped banks determine which areas did not have access to mortgage loans serviced by the Federal Housing Administration. The policy was implemented to help developers mass-produce suburban white neighborhoods, while at the same time prevent investment and development in redlined minority communities.

After a devastating flood damaged the Auraria neighborhood in June of 1965, city officials seized the opportunity to declare the area irreparable and ceased to grant building permits to repair damaged homes. In 1967, the Skyline Urban Renewal Project was voted into law and the city chose Auraria as the site to build the new college campuses for the Metropolitan State College of Denver, Community College of Denver, and, eventually, University of Colorado at Denver.

The project resulted in the displacement of numerous Aurarian families, the majority of Hispano and Mexican descent. The Hispano and Mexican American population living in Auraria resisted this displacement, but attempts to stop the project were ignored by the city, and demolition of their neighborhood promptly began. By 1972 and 1973, the entire community was forced out. Some moved into the adjacent Lincoln Park Homes, while others fled to other parts of the city.

This displacement is represented in the spray-painted mural History of the Westside Community by artist Marc Anthony Martínez. In it, Martínez paints the role of Hispanos, Chicanos, and Mexican Americans in Auraria and the Westside. On the right side of the piece, Martínez memorializes the influence of St. Cajetan’s Church, built between 1924 and 1926, which served as a cultural and religious center for the community. After Aurarians were displaced, the once sacred space of the community was converted into offices and an auditorium for the newly built campus.

Acknowledging the ancestry of Chicanos—while highlighting daily activities—Martínez depicts a mother hanging sports clothes from the neighborhood’s West High School out to dry on a clothesline. The imagery references the role of student activism during the Civil Rights Movement. In March, 1969, the students from West High walked out of school to protest discriminating remarks and the absence of the history of ethnic people in textbooks and ethnic teachers in Denver Public Schools. History classes failed to describe the important contributions of Black, Indigenous, Asian, Hispano, Mexican, and Latino peoples in Colorado and throughout the nation.

The West High School “blowout” also marked a pivotal moment for the developing Chicano Movement. That, in itself, was a continuation of a social justice movement that began with the annexation of Mexico’s territory in 1848 when the United States disregarded land and civil rights agreements promised to Hispanos and Mexicans in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Immediately following repeated actions to ignore the treaty, disenfranchised Mexican Americans and Hispanos began a movement to demand socioeconomic equality and an end to racial oppression in the country.

The term Chicano is not an ethnonym (an ethnic group), but a chosen social justice identity that was embraced in the late 1960s by primarily Mexican Americans and Hispanos from the Southwest resisting the injustice of racial discrimination in the nation. Coinciding with a grassroots neighborhood movement in Lincoln-La Alma Park, Auraria, and other neighborhoods throughout Colorado, Chicano youth across the country met in 1969 to draft “El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan” at the Chicano Liberation Youth Conference in Denver. Inspired by the Aztec creation story and their ancestral homeland, Aztlan, Chicanos proclaimed the American Southwest as their Aztlan. At the conference, Chicano youth drafted a resolution to publicly celebrate and teach through music, dance, theater, and art about their heritage and traditions.

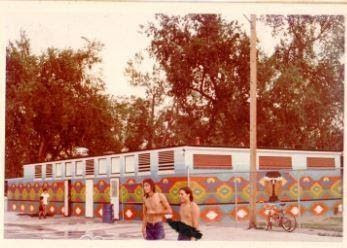

One of the early opportunities for this activism through art came at the Lincoln Park pool. At that time, many public swimming pools throughout the state were not accessible to people of color. In Denver, specific days were designated for “Blacks only” or “Hispanics only” to swim. In the Lincoln-La Alma neighborhood, community youth organized to challenge racial discrimination in the La Alma pool and police harassment in the park. The youth mobilized to establish a sense of permanency and cultural identity in the public park and pool within their community by changing the name of the park from Lincoln Park to La Alma (the Soul) Park and painting murals on the public park buildings.

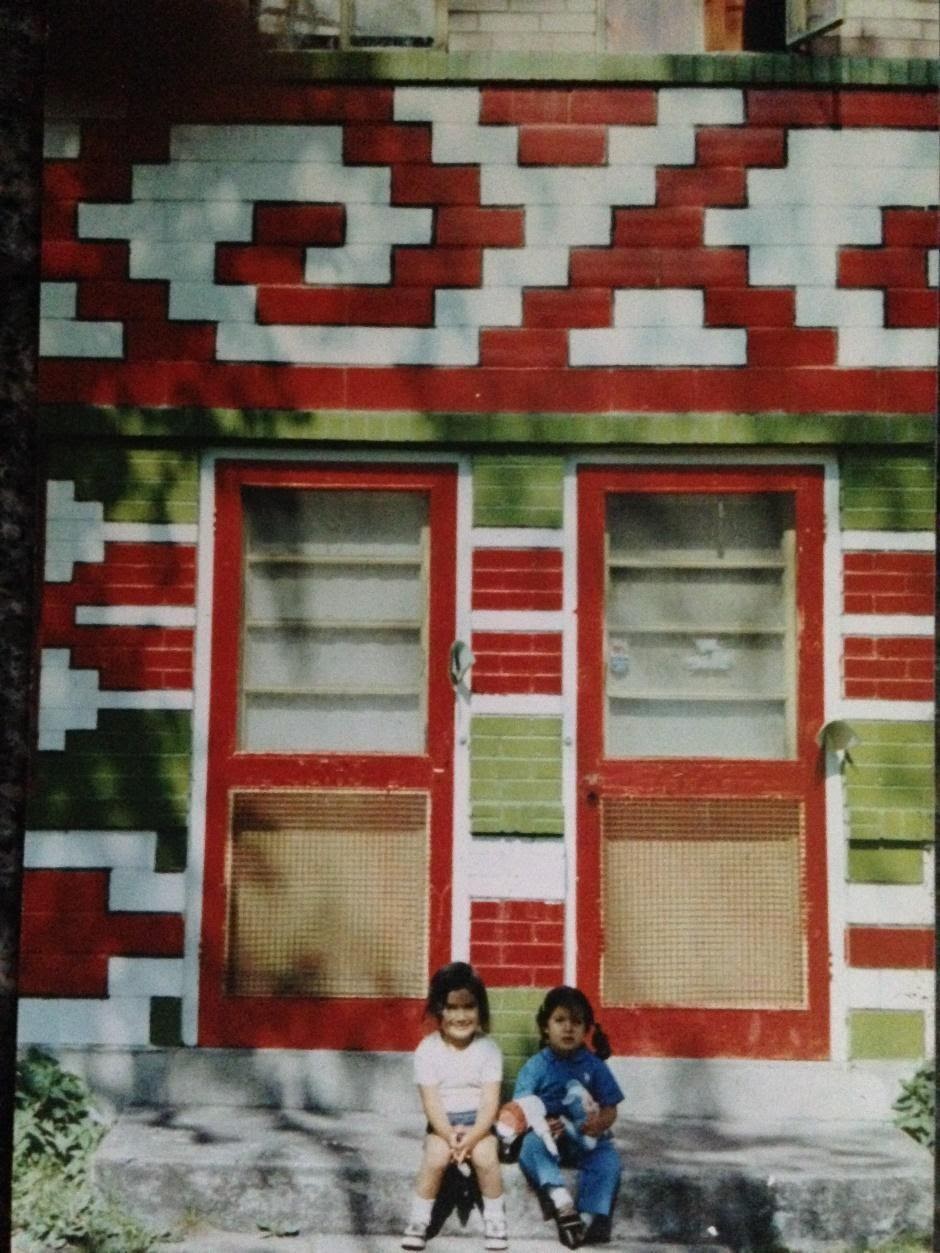

Mural by Emanuel Martínez painted in 1970 on the facade of his family’s home in the Lincoln Park housing projects. The author is on the right; her sister, Nacia, is on the left, 1974.

With the powerful application of murals, artists and people from the community challenged the status quo by questioning the prevailing racist ideology that plagued the nation. For historically marginalized communities repeatedly threatened and displaced, murals provided a sense of place within the greater landscape, hence legitimizing their right to live peacefully.

In 1970, as an artist and resident of the Lincoln Park housing project, my father, Emanuel Martínez, assembled youth volunteers living in the projects to participate in an art summer program. With recycled paint, Martínez designed narratives of Chicano heritage, and with the aid of the youth began to paint murals around the Lincoln Park housing projects, as well as the La Alma Park storage shed, and pool building. Gradually, the community and Chicanos began to take ownership of neglected parks throughout the city, connecting the community with their surroundings while improving the overall appearance of the parks.

Familiar faces and images on the walls of neighborhood parks created a sense of belonging and permanence in a space that was considered the soul of the community. Children from the community swam in the pools every day, while families listened to music, had picnics, and socialized. But the police closely monitored all activity in neighborhood parks—dispersing families and individuals if too many Chicanos were gathered. On at least three occasions, the Denver police arrived in riot gear to disperse crowds with tear gas at both La Raza Park (the name officially changed from Columbus Park recently) and Lincoln-La Alma Park during community events, injuring numerous residents.

The city attempted to suppress the surge of murals painted in parks, but their efforts were unsuccessful. By the mid-1970s, Denver and the state experienced an explosion of Chicano artistic expression and mural production. Between 1970 and 2000, the city, developers, and other outside forces did not benefit monetarily from murals. They often dismissed the cultural value of murals and many artworks were defaced or sandblasted.

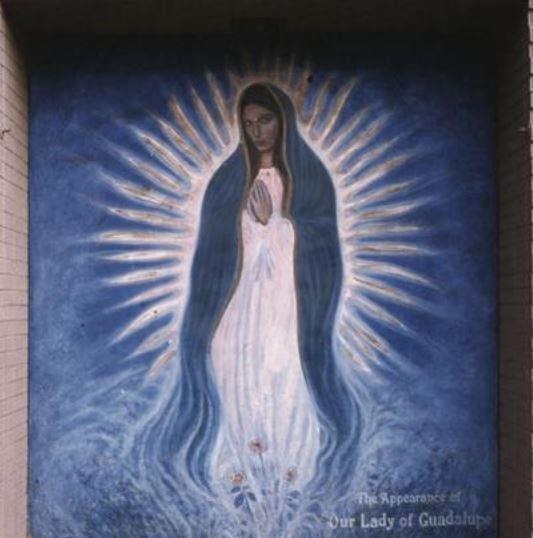

The Northside—one of the first Chicano, Hispano, and Mexican American neighborhoods to experience rapid gentrification in the early 2000s—was a locus of mural activity, beginning in the early 1970s. At the Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, which was founded in 1936 for predominantly Chicano and Mexican American Catholics, more than thirteen Chicano murals were painted from 1976 to 1996.

That surge in artwork was supported by Jose Lara. In 1961, Lara travelled from Navarra, Spain, to the United States to minister in Colorado. When he arrived in Denver, Lara was impacted by the extreme level of racial discrimination and segregation he confronted. Ordained in 1968, he quickly sought to support the Chicano Civil Rights Movement at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church and invited the United Farm Workers to use the basement of the church for their Denver branch. Between 1976 and 2001, Father Lara and, later, Father Pat Valdez supported local artists, including Andy Mendoza, Jesse Mendoza, James Romero, Jerry Jaramillo, Carlos Sandoval, Leo Tanguma, Emanuel Martínez, and Carlotta Espinoza by providing walls around the church to paint images of their faith, cultural heritage, and ancestral roots. Murals were painted inside the parish center, the interior and exterior of the church, and the hall. Today, all but one of these murals have been destroyed.

Carlotta Espinoza painted a mural in 1974 that stood behind the altar commemorating the apparition of the Virgen de Guadalupe, a powerful cultural symbol for both Mexicans and Chicanos. In Espejos, a film documentary by Minnie Paul, Espinoza explained that she chose to depict her “more like a Chicana, more like a modern woman.”

But, with changes to the Northside, the congregation of Our Lady of Guadalupe also shifted. A more socially conservative priest and congregation painted over the church’s exterior murals in the early 2000s, painted the interior murals, and built a wall to completely cover the Virgin of Guadalupe mural from public view. For Chicano community members who have attended this church for generations, this act of cultural erasure by the current congregation symbolized an unimaginable reality fifty years ago. To this day, the wall that covers the mural sparks heated debates between current and former parishioners who maintain spiritual and historical ties to the church.

Our Lady of Guadalupe by Jerry Jaramillo, Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, 1209 West Thirty-sixth Avenue, 1984.

Sadly, as historically marginalized communities are displaced in Denver, the public art—especially exterior legacy murals painted between 1970 to 2010—continue to be destroyed at an alarming rate. Many are in dire need of restoration. The majority of the murals painted during this period were led by artists or communities and were often painted for schools, churches, social organizations, and public spaces with the help of youth.

In 2009, Denver Arts and Venues implemented an Urban Arts Fund mural project “with the goal to create murals in areas that were deemed ‘graffiti hot spots’ and to provide positive creative experiences for youth to deter future vandalism.” Prior to this initiative, the City of Denver had often failed to recognize or support the community mural youth projects—led by artists living in their neighborhoods—that had existed for more than five decades.

Around the same time, Denver Arts and Venues began a mural permitting process to serve “as a liaison between artists, property owners, Public Works, and Community Planning and Development.” The service promised artists it would “help you make sure that your art fits any community guidelines or codes.” In establishing this permitting process, the move appropriated the content and form of community public art that once gave a voice to the disenfranchised and underserved and created a sense of place in their neighborhoods.

Denver, like many cities throughout the country and world, has aggressively used the arts to entice developers to regenerate and renew historically marginalized neighborhoods, also known as “artwashing” social spaces. As art historian Stephen Pritchard explained in a 2019 article entitled “Colouring in Culture,” artwashing often involves out-of-state artists and art collectives buying or renting properties in “deficient” neighborhoods where rent is relatively inexpensive in order to implement art projects. The intent, from the city’s perspective, is to entice private capital to invest in making neighborhoods more amenable by transforming the aesthetics of a neighborhood.

La Familia Sagrada by Carlos Sandoval, Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, 1209 West Thirty-sixth Avenue, 1982.

For example, founded in 2005, the River North Art District, or RiNo, quickly began to gentrify Five Points—historically a neighborhood of primarily Black, Hispanic, Mexican American, and Asian families. Artist collectives often target neighborhoods where properties are relatively lower priced and then use artistic practices and private funding to begin the process of social and cultural erasure, which often displaces ethnic communities.

In 2017, Denver awarded CRUSH Walls, a RiNo non-profit street-art festival founded in 2010, with the Arts and Culture Innovation Award to create “controlled graffiti” and murals. Controlled graffiti projects are often financed by developers and can attract thousands of tourists. New residents in the area have almost entirely displaced the working-class community of color in the last fifteen years.

Ironically, graffiti and murals—historically considered a supposed urban nuisance by government agencies—are used today by those same government agencies to entice settlement in “regenerated” and “renewed” neighborhoods. Like other cities throughout the country, developers and government agencies in Denver then pay artists or agencies who have recently set up a satellite office in the area to memorialize the displaced community by painting murals and graffiti of the displaced people.

Meanwhile, legacy community Chicano murals from 1968 to 2005 that were painted by artists with ties to the communities and that describe the people, places, and historical events that contributed to the character of Denver are defaced. Every year of late, several murals have been lost without the new resident or owner considering the cultural value of the paintings. For example, last April, I received several calls from the community informing me another cherished mural, Huitzilopochtli by David Garcia, in the Sun Valley neighborhood was whitewashed.

Prior to this act of cultural erasure, I had begun to meet with artists to document and archive murals throughout the city. Since 2018, art historians, anthropologists, historians, teachers, and I have created a grassroots organization: the Chicano/a Murals of Colorado Project (CMCP) to protect, promote, and preserve the visual legacy of Colorado. I have attended numerous talks and participated in meetings with preservationists and other mural organizations from Houston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia. I have repeatedly been informed that murals in preservation are often classified as only paint on a wall and few historic protections exist for community murals in the city, state, or nation.

This raised many questions for me and for the field of archaeology. How do we protect a painting on a wall when the building isn’t a historic building? How do we protect a mural when the artist or community doesn’t own the building? This is a completely different realm for preservation work and speaks to the larger problem of redlined communities and people, including artists, who did not have access to mortgages and other financial assets. There is no guide on how to preserve these works—yet.

The sterile description of a mural as simply a painted wall speaks to the systematic racism that has too often determined whose history is preserved in this country. In ancient Mesoamerica, Greece, Italy, and beyond, a mural is a priceless work of art, a testimonial of a once thriving community and sometimes a glimpse of their supernatural world perceived through the lens of an artist. Unfortunately, many of these murals were destroyed due to exposure to the elements and other factors. In Mexico, prehistoric and historic murals are considered part of the cultural patrimony of the country and their artists are celebrated. Similar to their predecessors, Mexican and Chicano muralists captured moments in time, to acknowledge individuals from the past and present. In Denver, the historical textbooks on the walls in the once redlined communities throughout the city described the narratives unique to Colorado, histories that were not and are still not accessible in schools or museums. Currently, we still do not have any protections or preservation plans in place to stop the destruction of these historical narratives of Colorado.

La Alma by Emanuel Martínez, La Alma Recreation Center, 1978. This work is one of the earliest remaining Chicano murals and commemorates the birthplace of Chicano Mural Movement in Colorado that began at La Alma-Lincoln Park neighborhood by Emanuel Martínez with the support of the community. The mural represents the accomplishments of Indigenous and Mestizo peoples past and present, as well as the role of the youth to continue their traditions and legacy. The Moon Goddess on the left gazes into Denver’s urban landscape, while the Earth Goddess on the right gazes towards a Puebloan landscape symbolizing the balance of both.

This meant that the only way that CMCP could seek justice for the Huitzilopochtli mural was to make an appeal to the property owner and the party responsible for painting over the mural. In this case, the property owner, the responsible party, the artist, and CMCP reached an agreement to restore Huitzilopochtli. In addition, they agreed to create an additional mural to help heal the community space. If successful, it will be the first time that we recover a whitewashed mural in Denver.

Unfortunately, a few months after Huitzilopochtli was painted over, I was informed the bottom half of another community mural, Mrs. God, painted by Carlotta Espinoza in 1998, was painted over with a new mural celebrating Covid-19 healthcare workers as the pandemic upended our lives. This mural was featured on the cover of the Spring 2020 edition of this magazine and inspired me to write this article. I reached out to the artist who painted over Espinoza’s mural to better understand the situation. The artist explained that because the mural was faded, he assumed it was acceptable to paint over it, noting it was very common in Denver to paint over murals to create a new one. The artist lamented his actions.

Using the approach we’d employed to restore Huitzilopochtli, I asked if the property owner would be interested in collaborating to restore and protect Espinoza’s historic mural. I was notified later that the owner is not interested in preserving the painting. Instead, I was informed that the building owner planned to create an artist collective in the building and he would periodically invite artists to paint a new mural on the wall.

Disheartened, I called Espinoza to update her about the status of the mural. She replied like all the first-, second-, third-, and fourth-generation artists respond when one of their murals is defaced: New people that move into the neighborhoods where we once lived don’t care about our art or our history.

From an archaeological perspective, when I drive through Denver looking for the places where I, my parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents once lived and socialized, I am aware that when and if archaeologists return to excavate the city of Denver in possibly five hundred years, there may be very little evidence of Indigenous, Black, Asian, Chicano, and Latino communities in the archaeological record if we continue down this path of cultural erasure and fail to protect the cultural heritage of all ethnicities that once lived in these spaces.

Huitzilopochtli by David Ocelotl Garcia, 8th Avenue between Federal and Decatur, 2008. The mural explores the creation story of the Mesoamerican deity, the patron of the Mexica/Aztec, Huitzilopochtli whose name translates to “Hummingbird of the South.” Facing south, the central figures, Coatlicue and her son Huitzilopocthli, stand within a vivid supernatural realm. The artist describes “the characters, objects, elements, and symbols represent spiritual ideas and philosophies specific to the healing of the mind, body, and soul."

In 2018, CMCP partnered with Historic Denver, the two La Alma neighborhood associations, and numerous individuals to help promote the protection of the historic Lincoln-La Alma neighborhood from potential erasure due to development and displacement. On August 2, 2021, Denver City Council voted unanimously to designate the neighborhood a historic cultural district—the second designation of this type in the city, and one of the first in the nation to recognize the role of Hispanos, Mexican Americans, and the Chicano Movement in the neighborhood.

In 2002, a six-block area on Welton Street in the Five Points neighborhood was designated a historic district by the Denver City Council. Yet it was only three years later that an art district was founded in Five Points, and a section of the neighborhood was rapidly rebranded as RiNo. In 2015, with RiNo now a thriving “new” neighborhood, the six-block area on Welton Street was renamed the “Five Points Historic Cultural District,” adding two more buildings to the amendment with an emphasis on goals of redevelopment per the Design Standards and Guidelines used by the Landmark Preservation Commission. As included in the guidelines, public art installation that could promote heritage tourism within the district was allowed.

The potential of the new Lincoln-La Alma Cultural Historic District encountering a similar fate remains to be seen. Already, many of the historic Chicano murals in this community have been whitewashed. CMCP is working to preserve and document others. To do so, we must create historic preservation practices to guide this work.

In my profession, I believe the disciplines of archaeology, history, art history, and preservation must apply their expertise and skills to responsibly recover and protect prehistoric, historic, and contemporary histories. The challenge for these disciplines is to evaluate how western standards and guidelines have historically ignored the unique qualities and characteristics of ethnic communities, while at the same time help them find solutions to equally recover, protect, and preserve their spaces, history, and cultural heritage.

*Editor's Note: We use Chicano/a/x here, initially, to reflect a growing movement toward using more inclusive and gender-neutral language in publishing. Chicano/a/x references people involved in the Chicano Movement in the 1960s and 1970s. It is composed largely of descendants of Hispanos and Mexican Americans, who value a connection to the Indigenous/Mestizo identity.