Story

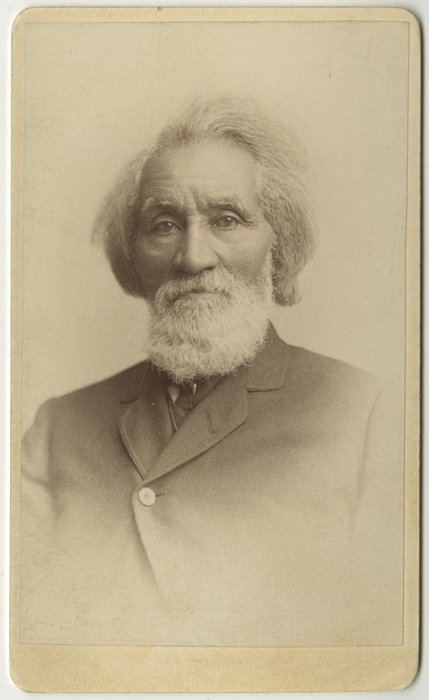

Henry O. Wagoner: African American Pioneer

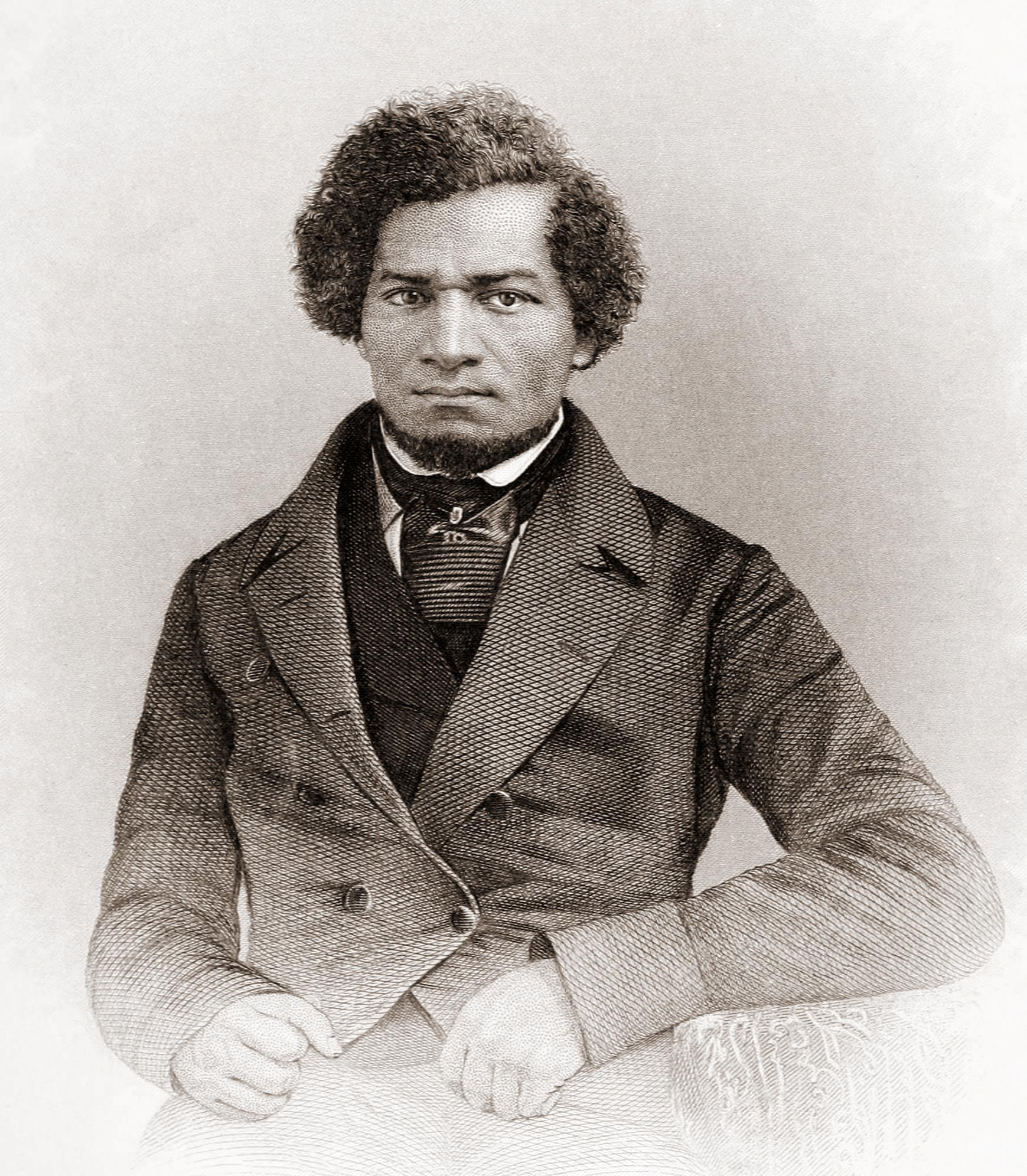

Long before he became a community leader and successful businessman in Denver, Henry O. Wagoner (1816-1901) was a staunch activist of the abolitionist movement, a typesetter and journalist for several radical anti-slavery newspapers, and a primary school teacher. He helped fugitive slaves escape to freedom via the Underground Railroad in Maryland, Illinois, and even in Chatham, Ontario in Canada. As an active participant in the anti-slavery movement, he met and corresponded with several prominent abolitionists of his era—and cultivated a close and enduring friendship with the indomitable orator and statesman Frederick Douglass. This formative and influential friendship lasted for fifty years. Though Wagoner was not a central figure of the abolitionist movement, he was certainly a prominent one, and his contributions deserve more than peripheral attention. Wagoner was unfailingly persistent in his efforts to assist fellow African Americans, and adamant about obtaining equal access to education, the right to vote, and the right to own property in a new era of territorial expansion and possibility.

Born on February 27, 1816 in Hagerstown, MD to a German father and an African American mother freed from slavery, Wagoner learned to read from his paternal grandmother. After working with the Underground Railroad in Baltimore, he headed West and worked as a primary school teacher in Ohio and Missouri before settling in in Galena, Illinois. Wagoner learned how to set type while working at the Northwestern Gazette and Galena Advertiser, and continued helping fugitive slaves navigate their way to freedom. In 1843, Wagoner moved to Chatham, Ontario, which was a popular end point of the Underground Railroad. He worked at the Chatham Journal and taught primary school. He was married in 1844 and lived in Ontario with his wife Susan, until they decided to move to Chicago in 1846. Over the course of their lives, they had seven daughters and a son.

Wagoner’s anti-slavery activism, business acumen, and close personal relationships grew in breadth and depth in Chicago. Prior to meeting Frederick Douglass in 1849 after one of Douglass’ public lectures, Wagoner wrote to him in January, 1848. “I must confess that I have felt a secret joy ever since I first heard your name spoken in connection with the “North Star.” The whole civilized world seems to have turned their attention somewhat towards the subject of human rights, therefore you will not be entirely alone in your new undertaking.” (Frederick Douglass Papers: 1842-1852, p. 286) He saw in Canada how community-based institutions could help black settlers purchase property, and was eager to share his insights.

“On looking abroad over this land, and reflecting on the impoverished condition of our unfortunate and disfranchised countrymen a plan has occurred to me, which, if it is worthy of notice, I beg you or some one [sic] else will urge its claims, after putting it into a favorable shape. [. . .] We are all too poor, as a general thing, and we must be awakened to every species of enterprise. [. . .] I would now say to you, to urge our people to push forward and make themselves owner of the soil. This certainly can be brought about by using great preserving industry, joined to the most rigid economy.” (Frederick Douglass Papers: 1842-1852, p.286-289)

It is clear this was also his personal philosophy. After working as an occasional correspondent for Douglass’ newspaper, Wagoner soon acquired a mill and became a businessman. He produced specialty southern-style corn meal, which was very profitable. Wagoner met Barney L. Ford, an escaped slave from South Carolina, who arrived in Chicago via the Underground Railroad. They became good friends, colleagues, and eventually brother-in-laws. Their close ties were established more than a decade before they fought for and eventually secured black male suffrage in Colorado in 1867, when Congress passed legislation prohibiting restrictions in male suffrage in all of the Western territories.

Wagoner moved to Denver in 1865, and established a number of businesses over the years. By 1870 he was considered to be one of the wealthiest African Americans in Colorado. He was active in Republican politics, and fought for equal access to education for Denver’s African American community. He and Lewis Henry Douglass, one of Frederick Douglass’ sons, taught reading and writing to black adults in his home until the Denver school board approved a segregated school building in 1867, and integrated public schools in 1873. A firm believer in the principles of democracy, Wagoner was appointed a clerk in the first Colorado Legislature in 1876, and later appointed deputy sheriff of Arapahoe County in 1880. He died at his home in 1901. Throughout the course of his life, Henry O. Wagoner consistently fought for the rights of African Americans, drawing upon his considerable political and social clout as a respected citizen and businessman.