Story

O’ My Sweet Highland Mary

In 1988 Bernice Lang donated her doll collection to History Colorado. Currently, staff and volunteers are working on the collection, originally started by Bernice’s mother, Minnie Belle Jackson, who came to Colorado by wagon as a child in 1867.

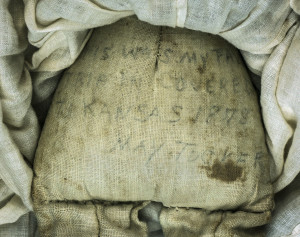

The project recently uncovered a doll with the inscription, “This was my favorite doll on our covered wagon trip to Kansas in 1878 May Tucker.” A little research revealed that the doll, owned at one time by May Tucker and acquired by Bernice’s mother and eventually Bernice herself, was manufactured by the German company Alt, Beck and Gottschalck (ABG). It’s what’s known as a china head doll, because the doll’s head and shoulders are of glazed porcelain—what we in America call china. For hundreds of years, the German province of Thuringia, where ABG was located, produced more dolls and toys than any country in the world. Rich with abundant deposits of quartz, feldspar and kaolin—the white clay used for porcelain production—Germany produced and exported millions of china doll parts yearly, including those used to make this doll.

In the mid to late 1800s china head dolls were often named and modeled after public figures like Queen Victoria, Dolly Madison and Mary Todd Lincoln. May’s doll is a Highland Mary, named for Mary Campbell, a Scottish woman immortalized by the poet Robert Burns, who wrote three famous poems in her honor. May’s Highland Mary is meticulously hand painted with beautifully detailed blue eyes, rosy cheeks and molded blonde curly bangs. While china parts may have been the same from doll to doll, rarely were any two finished dolls alike. Usually a mother or daughter would have created the clothes and a body out of scratch before attaching the head, shoulders and limbs. This doll is a good example of that. Her cloth body and goatskin arms are hand-sewn and she’s stuffed with sawdust.

Although we know a good deal about ABG and Highland Mary, we unfortunately know little about May Tucker, nor do we know how Bernice Lang’s mother came to own the doll. The one clue we do have is the inscription on the doll, which helps us imagine May as a young pioneer girl, on an adventure across the plains. Imagination helps us see a jolting wagon bouncing its contents and passengers; the prairie wind snapping the canvas top; the crunching of sagebrush under the wagon’s wheels; maybe a beloved pet dog scampering alongside in the shade of the wagon. One can even smell the horses and hear their whinnying and snorting—the clip-clopping hooves and creaking of leather harnesses. It’s not hard to imagine, day after day and mile after mile, a sky broken only by a pair of soaring red-tailed hawks and the horizon cut by a jackrabbit darting for cover; all the while, May Tucker sits nestled on the seat between her mother and father, cradling her beloved stuffed companion and wishing for a playmate with whom to play patty-cake.