Story

May Bonfils and Her Lost Belmar Mansion: A Lavish Lakewood Estate Housed a Wealth of Benevolence

Guest article by Dr. Tom Noel (15-20 minute read)

Today, Jefferson County residents know Belmar as a vibrant shopping, dining, governmental, and residential development that opened in the heart of Lakewood in the early 2000s. The main attraction, once known as Villa Italia, opened in 2004 as one of the state’s largest shopping malls. It has since evolved into a much larger commercial and retail complex that keeps expanding.

What shoppers, residents, and visitors may not know is that the name “Belmar” comes from the extraordinary estate built there by May Bonfils, daughter of Fredrick Bonfils. The Bonfils name—both famous and infamous—conjures not only Colorado’s most successful and feared newspaper tycoon but also his two feuding daughters, May and Helen, striving to improve and culturally enrich the lives of Coloradans.

Denver would never be the same after Frederick Gilmer Bonfils and his partner, Harry Heye Tammen, captivated and enthralled readers with big headlines, red ink, photographs, and sensational stories in The Denver Post. Fred Bonfils took an early interest in the neighboring town of Lakewood, where his daughter May would one day build her Belmar Mansion.

Born in 1883 in Troy, New York, May grew up in the Bonfils family’s Denver mansion at East Tenth Avenue and Humboldt Street. She attended St. Mary’s Academy, the most prestigious Catholic school in Colorado. There May earned a gold medal for her piano playing in 1899, encouraging her lifelong interest. Next came the elite Wolcott School for Girls in a building still standing at East Fourteenth Avenue and Marion Street. The school’s motto, “Noblesse Oblige,” May would take to heart. That Latin slogan stated that the well-heeled had an obligation to care for those less fortunate.

May’s affinity for humanitarian work was delayed if not thwarted by her decision to marry without her father’s permission. May hastily settled on a twenty-three-year-old Clyde V. Berryman, a sheet music and piano salesman with Wells Music. The couple eloped to Golden, where they married in a civil ceremony in 1904. Fred Bonfils exploded. May had wedded against his wishes, choosing someone he perceived as a poor nobody and marrying outside the Church. After May’s marriage to Clyde, it was Helen who became “Papa’s Girl.” Helen later admitted that she too secretly dated against her father’s wishes but always had her dates pick her up at May’s house. Fleeing her father’s wrath, May and Clyde Berryman moved to Omaha, then to Kansas City, then to Wichita, then to Los Angeles and Oakland, with Clyde trying to find work in music stores. While her father kept his distance, May’s mother, Belle, visited her as often as possible and sent money regularly. The Berrymans did not return to Denver until 1916 when they moved into a house Fred bought for them at 1129 Lafayette Street.

Fred Bonfils died in 1933, leaving the largest estate said to be probated in Colorado up to that time: $14,300,326 (about $269 million in 2018 figures). Upon the reading of his will, May found herself largely written out, leaving her a measly $12,000 a year. The will did stipulate that if May divorced Berryman her annuity would more than double. May went to court, where her lawyer argued that Bonfils’ will encouraged divorce and discouraged good morals. The court agreed, awarding May the same $25,000 annuity as Helen received. Frederick’s widow, Belle Bonfils, died two years after her husband. Her $10.5 million estate went primarily to Helen, again shortchanging May. Worse, May’s small share was set up as a trust fund to pay her the income. Even more insulting, Helen was to administer May’s trust.

May had her lawyer, Edgar McComb, contest the will. He charged that Belle had been unsound in mind and under Helen’s influence. In a court appearance that saw the two sisters angrily shout at each other, the court upheld May’s right to share evenly in her mother’s estate. Helen, however, retained control of The Denver Post, where she insisted her sister was never to be mentioned. May, in return, made snide remarks about Helen’s theater career to other news sources.

Though they were the opposite of charitable to each other, Helen and May’s good works would make the Bonfils name synonymous with benevolence. Helen set up the Helen G. Bonfils Foundation with her share, which benefitted worthwhile causes from the arts to education to healthcare. May funded the Bonfils Library–Auditorium at Loretto Heights College, a Catholic college for women in southwest Denver, and set up the May Bonfils Clinic of Ophthalmology at the University of Colorado Medical Center. She provided the mosaic murals, Stations of the Cross, statues, and reredos decorating the Catholic chapel of the United States Air Force Academy Cadet Chapel in Colorado Springs. She paid for an elegant 1934 monastery and prayer garden with a bronze statue of St. Francis of Assisi for the Franciscan Fathers who staffed St. Elizabeth’s Church in the Auraria neighborhood. Her instructions that the Franciscans spend on “the sick and needy” led to a free lunch line at the rear of St. Elizabeth’s Church—a program that operates to this day.

May oversaw these charitable works from her Belmar Mansion, which boasted twenty rooms including a walnut-paneled dining room, an art salon, and a small chapel off the foyer. May commissioned Jules Jacques Benois Benedict, Colorado’s most flamboyant architect, to design her dream house. Benedict trained at the Ecole de Beaux-Arts in Paris in the classical and renaissance traditions. Benedict said he designed Belmar “in the fashion of” the Petit Trianon with an exterior of “marbleized terra cotta.” Construction began in 1936 and was completed in 1937. At the end of a long, tree-lined drive, the residence reigned, guarded by an elaborate wrought iron entry gate and fence. Metal shields on either side of the gate flaunted the word Belmar. The gate posts were topped by statues of Pan playing his pipe. Inside the gates, visitors were greeted at the entry by a statue of Venus by the famed Italian sculptor Antonio Canova. The letter B, reminiscent of the B Napoleon Bonaparte used to rebrand Versailles as his own, highlighted a scroll over the main door. Glazed white terra cotta sheathed the gate posts, the eight-foot wall surrounding the property, the boathouse on Kountze Lake, and the mansion itself.

The Belmar's only surviving structure is the boathouse.

The library contained not only books and art but also replicas of famous statues May had seen in her European travels. Belmar had statues galore—atop the entry gates, in the mansion, and sprinkled around the grounds. The library harbored a giant table and cabinet said to be originals from Versailles. A Hans Holbein portrait of Queen Elizabeth I and works by Picasso, Corot, Correggio, Dufy, Holbein, Modigliani, van Dyck, and other art celebrities adorned the walls.

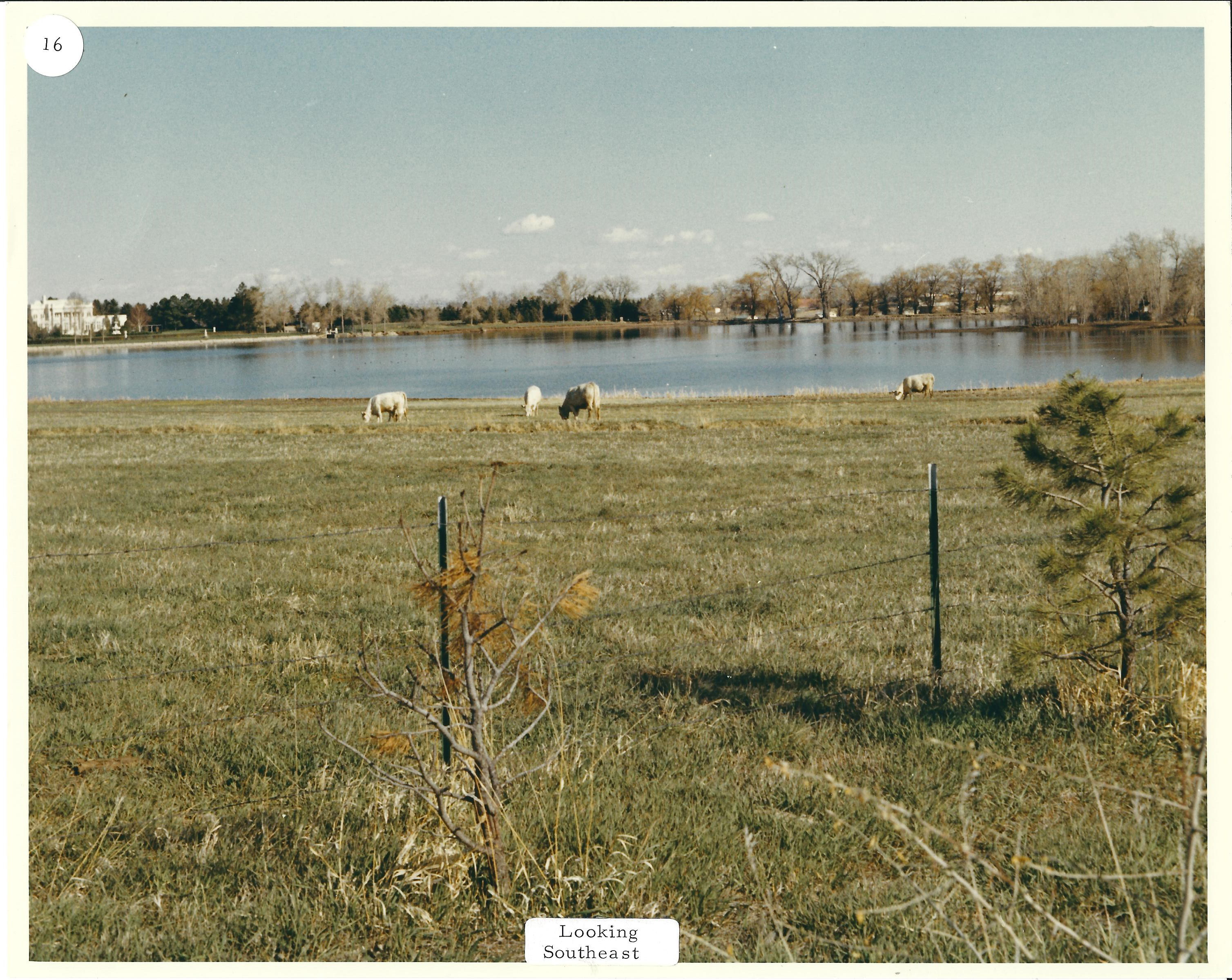

On the west elevation a solarium overlooked a three-tiered fountain with three crouching lions at its base. In 1953, May contracted with V. W. Gasparri of New York to purchase the $18,895 fountain of Italian biancho chiaro marble. Beyond the fountain, Belmar overlooked Kountze Lake and a then undeveloped natural landscape with a Rocky Mountain backdrop. She slept in a bed once owned by Marie Antoinette, sat in a crested chair that had supported Queen Victoria, and tickled a piano played by Frédéric Chopin.

The rooms of Belmar overflowed with European antiques. To house all of her growing collection, May in 1941 hired Colorado’s leading architect, Burnham Hoyt, to design a $36,000 art gallery addition to Belmar. Honoring her great grandfather’s service in the armies of Napoleon, May prided herself on a Chippendale case containing the original silk gauntlet that Napoleon had worn when he was crowned emperor of France.

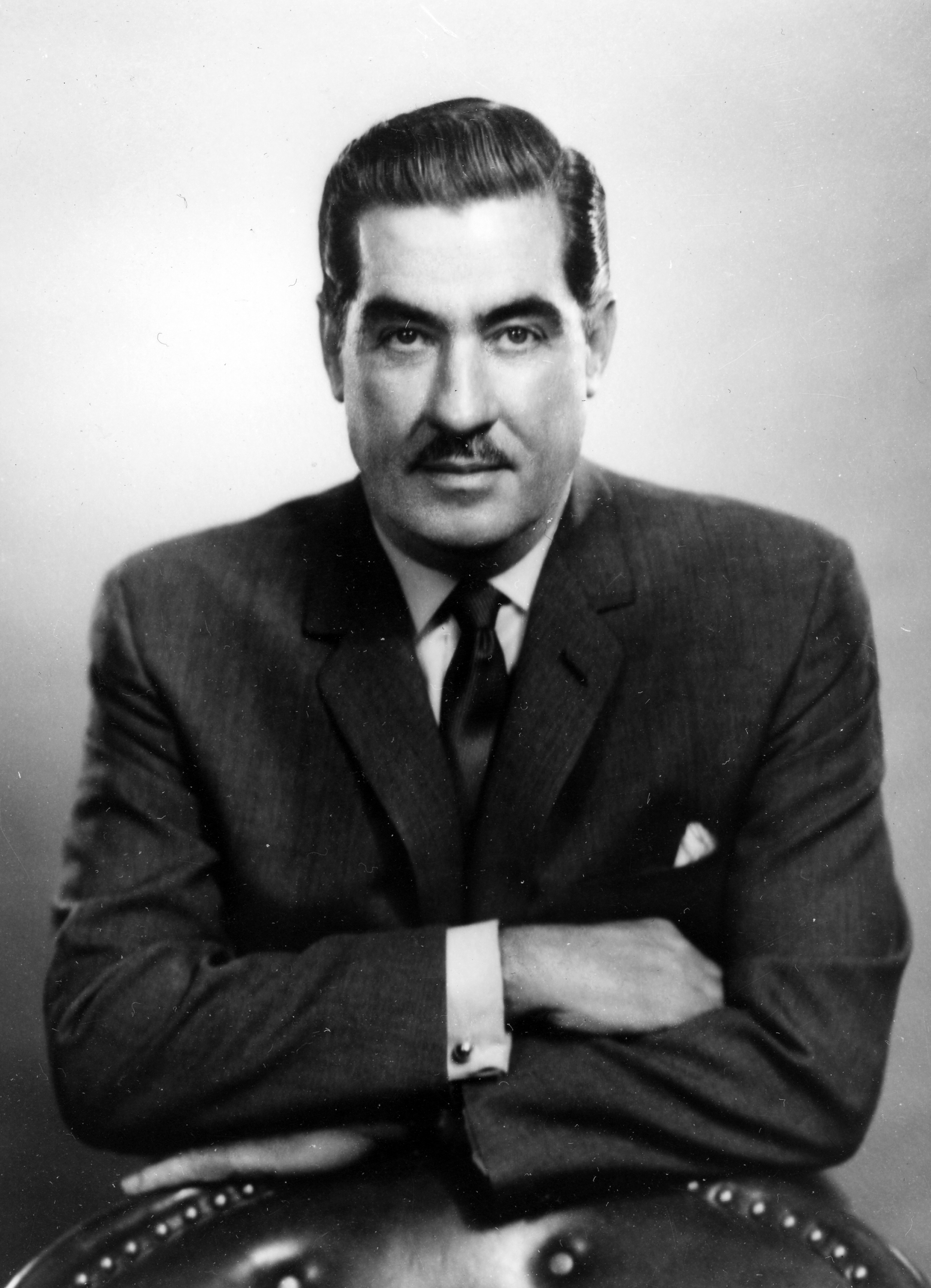

In 1943, May’s marriage to Clyde Berryman—with whom she had been separated for ten years—ended in a Reno divorce. Several years later, her friendship with interior designer Ed Stanton blossomed. While working for the Central City Opera House Association, Ed met one of the opera’s major financial donors, May Bonfils. May took a liking to this polite, most helpful young man. “He was charming, very friendly, a ruggedly handsome John Wayne type,” according to his barber, Jerry Middleton.

May’s possessions needed constant care and managing, and she tired of overseeing this all on her own. Though he was many years younger, she knew Ed would make a fine manager of her property and collections. One day May proposed: “If you marry me and enable me to live at Belmar, I’ll give you a million dollars. I want you to take care of me for the rest of my life. But you can’t just live with me; we have to be married.” As she had no children or major heirs, she wanted Stanton to handle her estate and see that it went to a worthy cause after she was gone.

They planned a wedding at Presentation of Our Lady Catholic Church in southwest Denver, but Church officials discovered that May’s first husband was still alive and revoked the Church’s approval. So May, age 73, married Ed, age 46, at Belmar Mansion quietly on April 28, 1956, with District Judge Robert H. McWilliams officiating. Only May’s nurse and Ed’s brother, Robert, attended.

Happy in her union with Ed, May kept mostly to her estate. Neighbors rarely saw her except for her frequent visits to the now-gone Lewis Drug Store at 8490 West Colfax, where she, her chauffeur, and her poodle would arrive in her Rolls Royce. She always ordered a cherry limeade for herself and an ice cream cone for her dog. The soda jerk and locals must have gaped at the befurred and bejeweled grand dame. For these excursions, May dressed to the hilt in clothing designed exclusively for her by the famous Sorelle Fontana fashion house in Rome. She also sporadically opened the beautifully landscaped grounds and gardens to visitors. In the summers, Brownie Girl Scouts, for whom she provided a ten-acre day camp site on the east side of Wadsworth Boulevard, frolicked around the yard.

May’s vision for Belmar went beyond the statues and furniture; she wanted an oasis. That vision not only included her collections but also wildlife. To protect wildlife on Kountze Lake and the rest of her property, May had Colorado officials approve it as “State Licensed Preserve No. 557,” where “hunting, fishing or trespassing for any purpose” were forbidden. She was protecting a herd of thirty mule deer and preening peacocks. May also bought swans to patrol Kountze Lake, along with wild ducks. After acquiring a permit for the purchase of migratory waterfowl in 1949, she brought from Canada some handsome black and white geese that flew in marvelous formations—thus introducing to Denver a species that would become far less rare and exotic.

The grounds were patrolled by armed security guards, who evicted (among others) Clyde Berryman—the former husband whose attempts to visit were not appreciated. Neighborhood youngsters also found the mansion irresistible. Katy Lewis, curator of the Lakewood Heritage Center, collects Belmar stories, including a confession from one old-timer that he and his friends used to break into the Belmar gardens to steal watermelons. Although armed guards patrolled the grounds, none of his group ever got caught, except for the time they brought a dog with them and he made too much noise. Still, they remained unreformed. They did not bring the dog again but they did keep going and always escaped unscathed—and with the watermelons.

Belmar’s vast grounds also housed the Belmar Farms, where May raised prizewinning Suffolk sheep as well as black Angus cattle, milk cows, and chickens. She kept meticulous records of how many eggs, chickens, and sheep were sold. On outlying fields, she raised oats and barley. May entered some of her finest livestock in the Colorado State Fair. Her sheep won prizes but never earned mention in The Denver Post—the result of her longstanding feud with her sister, Helen.

The Belmar Mansion also housed May’s stunning jewelry collection. The centerpiece of that collection was the Idol’s Eye. This 70.20-carat blue diamond, later surrounded by 35 carats of smaller diamonds in a dazzling necklace, was discovered around A.D. 1600 in the famous Golconda mines of India. Its name came from its early placement in the eye of an idol in a mosque in Benghazi, Libya. Later, Persian Prince Rahab lost it to Britain’s East India Company. The diamond then disappeared for 300 years until resurfacing in 1906 in the possession of Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid of Turkey. Stolen from Hamid, the Idol’s Eye disappeared again.

May bought the Idol’s Eye in 1947 from Harry Winston, the celebrated New York City jeweler. Winston made trips to Belmar and helped her collect other world-famous diamonds, such as the Liberator—a 39.80-carat Venezuelan gem named in honor of Simón Bolívar, who spearheaded South America’s liberation from Spain. From the Maharaja of Indore, May bought a celebrated diamond and emerald necklace. She collected a strand of ninety-five of the world’s largest and most perfect pearls.

To have fun with her collection, on special occasions May had an armored car bring her most prized jewelry from a downtown bank vault. As dinner guests watched in awe, she draped the Idol’s Eye over her poodle. As the diamond-bedecked dog scampered among the guests, May instructed the servants, “Don’t let the dog out!” To match her expensive accessory tastes, May bought a Rolls Royce Silver Cloud in 1959. The $20,000 car made headlines in Cervi’s Rocky Mountain Journal when it was delivered to her door. The article marvels at the custom car with its air conditioning, inlaid polished walnut interior, built-in picnic trays, and other luxuries.

May Bonfils Stanton died at her Belmar home on March 12, 1962, with Ed by her side. Records show that Helen did not attend her sister’s funeral. As May’s custom mausoleum was under construction in Fairmount Cemetery, Helen allowed May to be only “temporarily” placed with her parents in their memorial crypt.

May’s will left almost half of her estate, estimated in total at $30 million, to her husband, Ed Stanton, who also received the mansion, its furnishings, and fifteen acres of the grounds. She left $2,500 each to her nurse, watchman, and ranch foreman and $2,000 each to her cook and secretary as well as $1,000 for the care of her dog and cat. Ed Stanton donated Belmar Mansion and ten acres of its grounds to the Archdiocese of Denver in 1970 “for religious purposes only.” But the Archdiocese found both the mansion and the land a challenge to maintain. A spokesman for the Archdiocese complained that “the mansion’s normal maintenance was $1,000 a month and that a year’s effort to find appropriate use of the estate had been unsuccessful.” Stanton sold or leased much of the square-mile site east of Wadsworth Boulevard for Villa Italia Shopping Center and other retail uses. By donating land for Lakewood’s government center, a public library, and the Lakewood Heritage Center, he played a key role in reshaping Belmar into the governmental and retail center of Lakewood.

May’s world-class jewelry collection was auctioned off at the Parke-Bernet Galleries of New York City in 1962. The Idol’s Eye sold for $375,000 to Harry Levinson, a Chicago jeweler, and is now in the Smithsonian. The vast art collection was auctioned off in 1971.

Honoring May’s legacy of philanthropy, Ed formed the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation. The money raised from auctioning May’s jewelry and art collections supported this foundation in its original efforts. In 1981, the foundation made its first grant—a donation of $100 to the Park People, a nonprofit dedicated to maintaining and improving Denver’s often underfunded public parks. This preliminary grant was followed by $5,000 to help the Park People restore the Washington Park Boathouse, a beloved amenity that had fallen into disrepair.

In 1982 the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation made its first major gift: $125,000 to the Denver Botanic Gardens to establish the May Bonfils-Stanton Memorial Rose Garden. A follow-up grant funded a lecture series at the botanic gardens, which continues today. Another early beneficiary was the Central City Opera, where May and Ed had met.

The questions remained of what was to become of Belmar Mansion. Stanton rejected the idea of a museum, saying a home should be for the living and a museum was for the dead. Others claimed May did not want any other woman sleeping in her home. The Archdiocese ultimately sold the property for $350,000 to the Craddock Development Company of Colorado Springs. In 1971, the City of Lakewood issued Craddock a demolition permit for a two-story, 8,661-square-foot private residence with a two-car garage and a basement. The demolition made way for a $3 million office park named “Irongate Executive Plaza” for Belmar’s surviving grand entry gate. What had once been one of Colorado’s most palatial estates became a generic office park. Before demolition in 1971, the statues and other fixtures, inside and out, were sold off. Sale of the mansion and grounds facilitated the construction of Lakewood Town Center, complete with its civic and cultural amenities, as well as Villa Italia Shopping Center.

Proceeds of these sales went to the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation to support its charitable mission throughout Colorado. The foundation awarded grants to a variety of Colorado nonprofits—from homeless shelters to healthcare. In 2012, the trustees voted to allocate all of its philanthropy toward Denver’s arts and cultural organizations—reflecting a desire to focus on a key need at a time when many other local funders had reduced their support for the arts. Meanwhile, the cultural sector was growing more essential to the vibrancy of the Denver community.

Today, the Belmar Mansion is remembered for its beauty and splendor but more importantly for the charitable works of its owner. May Bonfils Stanton was as peculiar as she was philanthropic. She found joy in living lavishly and generously, and her efforts, and those of her husband, set a course of generosity that thrives to this day.

For Further Reading

The author thanks the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation for their support of this essay, which is based on a much longer, forthcoming history of the foundation. Gary P. Steuer, president and CEO, initially proposed the project and has been most helpful as a guide and editor. Dorothy Horrell, the previous CEO and executive director and now chancellor at the University of Colorado Denver, provided an interview and images. Monique Loseke, executive assistant, made us at home in the D&F Tower and provided advice and editing as well as opening up all materials. Caitlyn “Katy” Lewis, museum curator at the Lakewood Heritage Center, could not have been more welcoming and helpful. She gave us a grand tour of the many remnants of the Belmar Mansion and farms. Katy also provided many images, stories, and good ideas. Graduate student Evan West served as a research assistant. Special thanks to Kristen Autobee, Kathleen Barlow, and Vi Noel. As usual, the staff at the Denver Public Library Western History & Genealogy Department and the Hart Research Library at History Colorado have been wonderful collaborators.

The author relied on the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation’s files and clippings as well as the Bonfils-Stanton Family Papers, 1899–1999, at the Denver Public Library’s Western History and Genealogy Department. For more about May Bonfils and the Belmar Mansion, see Thomas J. Noel, Stephen J. Leonard, and Kevin E. Rucker, Colorado Givers: A History of Philanthropic Heroes (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 1998); Marilyn Griggs Riley, High Altitude Attitudes: Six Savvy Colorado Women (Boulder: Johnson Books, 2006); Dorothy J. Donovan, “Beautiful Belmar,” Historically Jeffco (Golden: Jefferson County Historical Society), Summer 1994; and Lasting Impressions: The Recipients of the Bonfils-Stanton Award in Their Own Words (Denver: Bonfils-Stanton Foundation, 2010).

Thomas J. Noel was named in 2018 the State Historian of Colorado and the chair of the State Historian’s Council of History Colorado. He is a professor of history and director of Public History, Preservation & Colorado Studies at the University of Colorado Denver. Noel is the author or co-author of fifty-three books and many articles. He was a longtime Sunday columnist for The Denver Post and the Rocky Mountain News and appears regularly as “Dr. Colorado” on 9News’s “Colorado & Company.” He completed his B.A. at the University of Denver and his M.A. and Ph.D. at the University of Colorado Boulder.