Story

Colorado’s Hispanic Towns

Real or Ghosts?

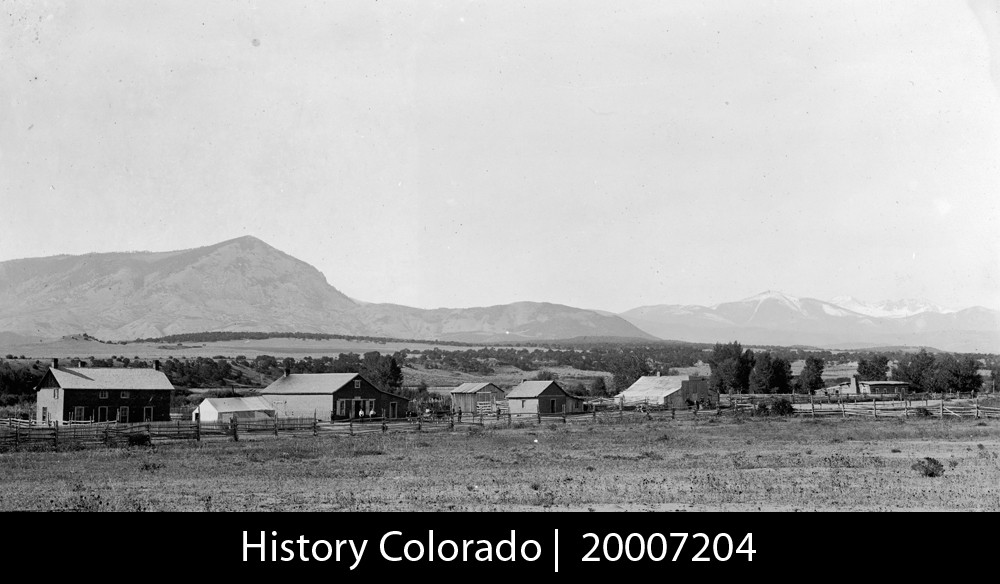

On the upper Huerfano River amid the Greenhorn Mountains, this isolated unincorporated ranching town is the shrunken hub of a large mountainous chunk of northwestern Huerfano County. Gardner's roots, however, lie in a predecessor Hispanic town, according to tales I heard in the Gardner Tavern.

Thomas J. Noel, Colorado State Historian and Professor of History at the University of Colorado Denver

At the Tavern, after putting a pinch of salt on the rim of his sweating beer can, Augustino Garcia nodded a welcome. I mounted the barstool next to him in the dim tavern. He was the first person I had seen in Gardner where this tavern was the only sign of life. This dusty, sleepy village on the upper Huerfano (Spanish for orphan) River seemed to be a ghost.

Glad to find another human being, I bought Tino a beer. After a few more beers, Tino grew talkative: "A long time ago, before Gardner, there was another town here. My father told me about it. It lay down in the valley next to the old river bed. My great-grandfather lived and died there."

Augustino told me some of the stories he heard as a boy. Chavez Town church he seemed to remember best. It had a flat dirt roof so leaky that it rained indoors for days after the rain stopped outdoors. The church seemed wet and cold for years until a stranger appeared one day and offered to repair the roof.

"He was a man so strong, that he needed no ladder," Garcia said, jamming a lime wedge into a fresh can of cerveza. He shook his head. "He just threw shovel fulls of mud high up on the roof. After that it did not rain inside the church anymore. Some of the people though it was a miracle. They thought this man must have been Jose, the carpenter, come to help his people."

St. Joseph may have saved the chapel, but he did not save the town. Garcia had no idea what year Chavez Town drowned. Every spring the Huerfano River swells and sometimes it floods. One year, the river rose angrily and washed over its banks into Chavez Town. The people who could rushed to higher ground. Looking back, they saw their village sink under the rising waters.

For days, for weeks, the people of Chavez Town waited. But that year, despite all the prayers of a pious people, the river did not leave its new flood bed. Chavez Town was buried in a watery grave. Townsfolk were orphaned by the Huerfano River, whose name in Spanish means orphan which is what Spanish explorers called the solitary black volcanic hill out on the plains beside the river and I-25.

The orphaned residents of Chavez Town moved uphill to a new town two miles away that the Gringos called Gardner. Herbert Gardner, the son of a governor of Massachusetts, had amassed land and founded the town. "He named it for himself, not for one of the saints or for the Chavez family who first settled here," Garcia said shaking his head.

"My great grandfather owned a lot of land which he gave for the Chavez Town Cemetery," Augustino said. He took a small pinch of salt, savored it, then washed it down with the rest of his beer. "Granddad was the first to be buried there in 1941, and then we put my father there, too." Like Chavez Town, these pioneers lived on in the memory of a son grown old.

"Most of families still left with any land have to send menfolk to find jobs elsewhere in order to survive. In the spring we start out in Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana for spring sheep shearing. There's haying work here in the Huerfano Valley in the summer. Come fall, we go to the San Luis Valley to harvest potatoes. But it’s worth it to stay here. This is a better life than most places. We're blessed. The mountains stop the wind, and catch the clouds, and make the rain. We don't have the dust and the drought they have down on the plains."

The next morning Augustino took me to the Chavez Town site two miles southeast of Gardner. He dug up some broken dishes along the sandy banks of the shriveled river. Then we visited the tiny cemetery with its crude wooden and cement headstones amid a few plastic flowers and much cholla cactus. We paid our respects to Augustino's ancestors.

Back in Denver I visited History Colorado’s Library. One of the librarians lugged out the oldest Colorado maps they have. We could not find it on Hayden's 1873 Atlas, the 1877 Post Office map of Colorado, or the giant Rand McNally maps for the 1880s and 1890s, or about 70 other early maps. Nor does Chavez Town show up in any of the ghost town guides or Bill Bauer and Jim Ozment's Colorado Post Offices, 1859-1989. After a day long search, I could find no trace of Chavez Town. Both the town's life and death have gone unreported. It lies under the Huerfano River that once gave it life.

Chavez Town, I am still convinced, was not a barroom fantasy. Like other Hispanic towns never put on a map and never given a post office, it is gone, except for the stories of a few old timers reminiscing in the Gardner Tavern.