Story

A Brief Walk Along Denver’s Notorious Market Street

(12 minute read)

From its beginnings as an unruly mining town, Denver was described as “most lively...in any and all kinds of wickedness.” The writer, prospector William Hedges, went on to doubt that there was ever “a place on this continent where a greater amount of evil to the square acre was so spontaneously and openly developed” (quoted in Clark Secrest’s Hell’s Belles). Wickedness ran rampant no more openly than on Market Street, nee Holladay Street, nee McGaa Street. Denver’s notorious vice district, known as The Row, teemed with opulent parlor houses, maisons de joie, common brothels, dancehalls, hurdy gurdy houses, and lowly cribs.

Here we offer a tour of “Hell’s Swift Alley" that you can take by way of reading or by walking to the designated (or approximate) locations.

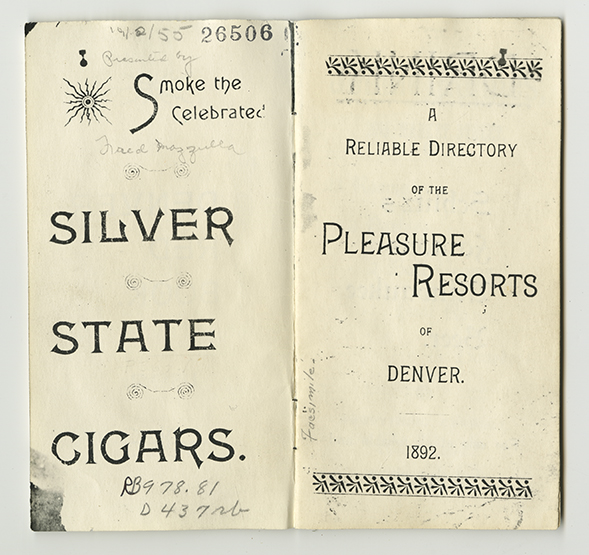

The Denver Red Book was a pocket-sized publication for the gents that fit conveniently in one’s breast pocket and was, as advertised, a “reliable guide to the pleasure resorts” along Market Street. Published maybe-not-so-coincidentally in time for the 1892 National Conclave (allegedly the biggest assemblage of out-of-towners in Denver to that date) and the opening of the Brown Palace Hotel, the Red Book directed Market Street’s visitors to the best houses extending a “cordial welcome to strangers” and promising “all the comforts of home.”

A similar publication from 1893, the Traveler’s Night Guide to Colorado advertised such Row establishments where the lady of the house would be “pleased to discuss with Yourself and friends the Political Aspect of the day.” Even before the Red Book and Night Guide, in 1882 the Denver Republican reported a story about The Rustler, an “immoral paper,” and The Patrol, which was “devoted to advertising the cyprians on Holliday [sic] street, and was filled up with literature of that class.”

With these as our guides, let’s step out and catch a peep of the half-world in this area of Denver.

Gamboling along Market Street, heading west from 20th Street, one could visit Belle Birnard’s at 1952 Market. Belle’s boasted 14 rooms, five parlors, choice wines, liquors, and cigars—“strictly first-class in all respects.” Twelve “boarders” entertained at Belle’s.

The women who worked at a parlour house such as Belle’s were expected to be talented, attractive, well-dressed, and abstemious from drink. Earning $30 to $100 an evening for the pleasure of their company, a parlour house girl paid 50% of her earnings to the proprietress of the house, plus room and board. Many women began a life on The Row as a way to make money when few other professional options existed for women and “respectable work” as typists, clerks, seamstresses, laundresses, and domestic servants paid meager wages, as little as $1 a week.

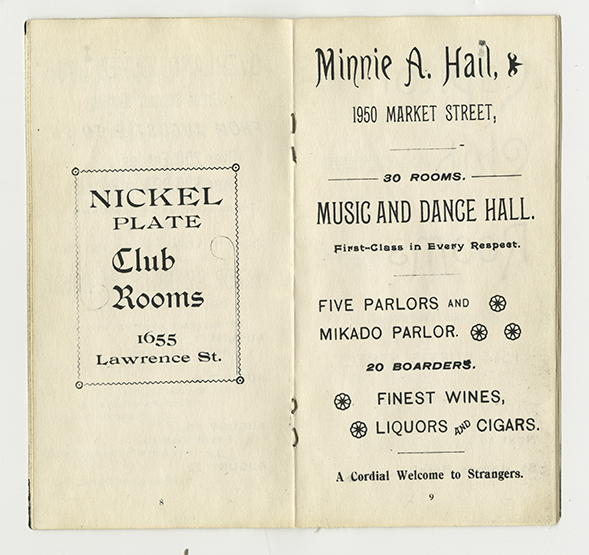

Minnie A. Hall’s establishment at 1950 Market Street was advertised as “First-Class in Every Respect.” Minnie’s parlour house was even more well-appointed than Belle’s—30 rooms, a music and dance hall, five parlors including a lavish Mikado parlor, and 20 boarders.

The Denver Post in 1896 reported that Minnie’s was the stop of three merry makers in town from Philadelphia who’d embarked on a drinking spree with a few “giddy members of the demimonde.” Pickpockets and sneak thieves flagrantly relieved visitors to Market Street of their money and possessions, and so one of the gents had the forethought to sew his cash into his underclothes. During the course of this carouse, the party was “seized by the happy idea that to change costumes would be a proper caper.” Willie Crawford, one of the the demimondaine, cut a striking figure in “creased trousers, red tie, cutaway coat, and patent leather.” The fellow from Philadelphia, however, “resembled last years’ birdsnest in the bedraggled lingerie of sin.” After the clothing was sorted out, the money had gone missing. The Philadelphian “howled for the police.” Willie denied any knowledge of the money. At the threat of their debauch being made public in the police reports if they pressed charges, the men made a hasty departure—poorer but wiser.

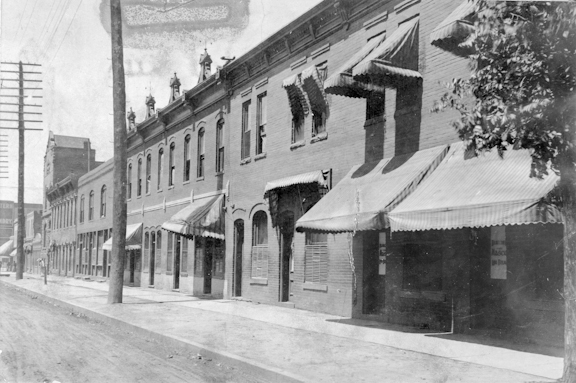

A few houses down, Market Street habitues would find the gem of The Row, Jennie Rogers’ House of Mirrors. This former palace of sin, while only a ghost of its disreputable glory, is still standing at 1942 Market. Named perhaps for the ballroom hung floor to ceiling with mirrors three feet wide in oval frames carved with the figures of nude women, the House of Mirrors itself is the stuff of scandal.

Jennie Rogers came to Denver from St. Louis in about 1879 or 1880, leaving behind her paramour, the St. Louis chief of police. After managing several houses along The Row, she rented the building at 1942 Market from Minnie Clifford in 1888.

Minnie was notorious in her own right as the only madam in Denver in whose house the infamous “cancan” was performed. The National Police Gazette in 1880 salaciously noted, “those who have seen these dances say that they excel in lewdness anything ever witnessed in this city. They are orgies which would delight the basest taste.”

Minnie, in a sly bit of business, sold the house from under Jennie to a Mary Leary for $10,000. Jennie offered Mary $12,000 and then scraped the house to build the House of Mirrors.

The House of Mirrors in its later days as a Buddhist Temple, Fred M. Mazzulla Collection. 10037400

The story goes that the chief of police secured the money to build Jennie’s House of Mirrors by blackmailing a Denver businessman who had political aspirations. Jan MacKell relates in Brothels, Bordellos, & Bad Girls that the businessman’s young wife had recently disappeared, conveniently providing an opportunity for him to marry the very recently divorced and wealthy wife of his former employer. Suspicions and rumors about the demise of the businessman’s first wife gave the police chief the chance to launch Jennie as Queen of the Line. Allegedly, the chief misappropriated the bodily remains of an unknown female, secretly reburied them in the aspiring politician’s back garden, and within days made an “official” visit to the hapless businessman in order to search the premises. Upon finding the bones, whoever’s they might have been, the chief swore himself to secrecy at the cost of the $17,000 (and change) needed to finance Jennie’s new enterprise. The businessman, hoping to avoid a public and reputation-damaging trial, agreed to the terms. Jennie got her house, but, alas, the businessman never won public office.

Designed by William Quale, who also designed Denver’s Trinity Methodist Church, First Congregational Church, and West High School, the House of Mirrors includes a curious bit of ornamentation. From the street you can still see carved into the third-story facade a bust of a woman, thought to be Jennie herself, and the faces of a gentleman, a stout woman, a young lady, and an older man. Jacqualine Grannel Couch, in Those Golden Girls of Market Street, speculates whether they are caricatures of the cuckolded employer, his ex-wife, the businessman’s first, ill-fated wife, and the doomed businessman himself.

Jennie’s new house was so popular that she bought the building next door, 1946 Market Street, and opened a passageway between the two to entertain the overflow of patrons, which included members of the state legislature, who adjourned to Jennie’s in the afternoons. The Rocky Mountain News reported, “Each afternoon about 3 o’clock, the august lawmakers would retired to Jennie Rogers’ Palace of Joy on Market Street, and there deport themselves in riotous fashion.”

Ambling past the House of Mirrors to 1916 and 1922 Market Street, one could visit the parlour houses of the Queen Mother of the Row, Mattie Silks.

Described as “well-upholstered and an accomplished hell-raiser,” Mattie conducted business on Market Street for around 40 years between the late 1870s, when she’s first mentioned in The Denver Post for being arrested for drunkenness, and 1915, when Denver’s vice district was “officially” closed.

Mattie opened her first sporting house in Springfield, Missouri, at the age of 19 and boasted that she was “always a madam, never one of the girls.” She was later quoted in Max Miller’s Holladay Street to say, “I went into the sporting life for business reasons and for no other. It was a way for a woman in those days to make money, and I made it…. I never took a girl into my house who had no previous experience of life and men...and they came to me for the same reason that I hired them. Because there was money in it for all of us.”

Besides 1916 and 1922 Market, Mattie purchased the House Mirrors in 1911 after the death of Jennie Rogers in 1909, inlaying her name in black and white tile on the threshold. Mattie died at age 83 in 1929. Both Jennie and Mattie are buried in Fairmount Cemetery under the names Leah J. Wood and Martha A. Ready, respectively and respectably.

Across the street were such addresses as 1905, 1911, 1925, and 1957 Market Street. Not mentioned in the Red Book, these were lowly, narrow cribs, tucked in between the saloons where Denver’s fancy men gathered, the gambling hells, and variety theatres like The Circus (1913–1917 Market Street), a three-story venue where the sports paid $1 on Saturdays to see risque shows.

According to scholar Cheryl Siebert in Denver’s Disorderly Women, between 1870 and 1900 there were about 600 women working as “crib girls” or on the streets of Denver. At as little as 10 cents a transaction, profit lay in volume, and the rent on their cribs was collected daily at a cost of $15 to $25 a week. Dressed in low-necked, knee-length dresses or loose-fitting, easily removed white Mother Hubbard gowns, crib girls would call from their doorways, “Come on in, dearie.” Failing to draw in a customer that way, they might snatch a gent’s hat and throw it into their crib, snagging a customer as he went in to fetch it.

The life of a Denver crib girl could be hard, brutal, and dangerous. The average career working in the cribs and streets was about five to seven years before women left the profession--moving on to another town or state (changing their names for respectability’s sake), marrying, finding other work, or being “reformed.” But often, the women who worked on Market Street—from the parlour houses to the cribs—died from violence, drug overdoses, and disease. Suicide was epidemic, reportedly two to three suicides or attempted suicides a week among the denizens of Market Street. Isolation from family, hard living, addiction, money and legal woes, and untenable despair preyed on the working girl. Morphine, laudanum, carbolic acid, and “Rough on Rats” were among the preferred methods of women who “sought to shuffle off this mortal coil” as the newspapers of the day would have it.

Back across 20th Street was 2015 Market Street, advertised in the Red Book as 23 rooms, three parlors, two ballrooms, a pool room, 15 borders and “everything correct.” It was opened in 1888 by Amy Bassett, who was allegedly from a wealthy, respectable Kentucky family and had fled her marriage to the son of a former Ohio governor because of family trouble that had “threatened good names and reputations.” She moved to Denver and led “the wildest life of all the wild ones.” Besides 2015 Market, she worked in and owned many houses on The Row. It was believed that she had a son and a daughter living in the East and she paid her son’s way through Yale with her earnings.

Amy Bassett suffered a horrific death in her parlour house in 1904. When she poured gasoline into a shallow bowl, which she was using to clean a hair switch, fumes filled the bathroom. The friction between the brush and the hair extension ignited the gasoline and the fumes, and fire engulfed Amy and the room. An officer on his beat rushed in and rescued Amy, taking her across the street to 2020 Market, once known as the “House of a Thousand Memories.” But Amy soon died at the hospital, at the age of 38. The Denver Post, in reporting her death, noted that every year she’d dropped her assumed name and gone quietly back East to visit her children, never allowing her people to visit her in Denver. “Indeed, it is not likely that they know where she is.”

In February 1913, the Rocky Mountain News pronounced that Denver’s redlight district was “abolished by the fire and police board…. There was a hurried exodus by women when the word came. All were told that the word was final and there was to be no dallying.” Although Market Street is but a vestige of its former wickedness, with most of the houses having been converted to warehouses or razed, the spirits of the women who lived, worked, played, loved, fought, and died on Market Street still linger.

This jaunt along Market Street offers only a glimpse of life on Denver’s Row; there are multitudes of Colorado stories to be discovered and recovered in the Hart Research Library at History Colorado, which has collected and preserved the history of lives that are too often lost in the shadows of time. The following resources from the library’s collection significantly informed this writing:

- A Reliable Directory of the Pleasure Resorts of Denver (1892)

- Traveler's Night Guide of Colorado (1893)

- The Fred M. Mazzulla Collection

- Colorado Historical Newspaper database for historic content from The Denver Post and Rocky Mountain News (available onsite at the Hart Research Library)

- Butler, Anne M. 1987. Daughters of Joy, Sisters of Misery: Prostitutes in the American West, 1865–90. Urbana: University of Illinois Press

- Couch, Jacqualine Grannell. 1974. Those Golden Girls of Market Street: Denver's Infamous Redlight District; an Historical Glimpse. Fort Collins, Colo.: Old Army Press

- Dallas, Sandra. 1971. Cherry Creek Gothic: Victorian Architecture in Denver. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press

- Goodstein, Phil H. 1993. The Seamy Side of Denver: Tall Tales of the Mile High City. Denver: New Social Publications

- MacKell, Jan. 2004. Brothels, Bordellos, & Bad Girls: Prostitution in Colorado, 1860–1930. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press

- Mazzulla, Fred, and Jo Mazzulla. 1973. Brass Checks and Red Lights: Being a Pictorial Pot Pourri of Historical Prostitutes, Parlor Houses, Professors, Procuresses and Pimps

- Miller, Max, Margaret Miller, Fred Mazzulla, and Jo Mazzulla. 1971. Holladay Street. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Secrest, Clark. 2002. Hell's Belles: Prostitution, Vice, and Crime in Early Denver: With a Biography of Sam Howe, Frontier Lawman. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

- Waite, Cheryl Siebert. 2001. Denver’s Disorderly Women: Prostitution and the Sex Trade, 1858 to 1935. Master’s thesis