Story

Mission 66

Our National Park Legacy

My love for National Parks did not arise from family vacations. When I was young, we took few road trips that deviated from the long drive from Chicago to Florida to visit my grandparents and go to Disney World.

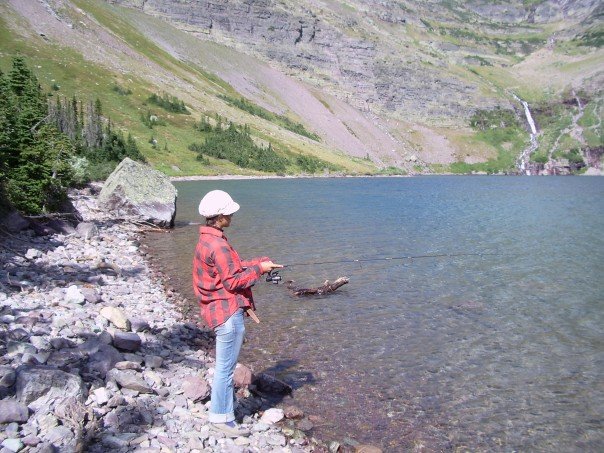

My parents were not outdoorsy, which was perhaps the reason I fell in love with camping as a teenager and have become an avid camper as an adult. Backpacking through Glacier National Park in college was my first foray into the wild, but also into the grandeur of the National Park System and its architecture. Century-old lodges next to rentable lake cabins, all with indoor plumbing, sounded very luxurious to someone whose first experience with the wilderness was a week-long backcountry trip where we fished the glacial lakes for dinner.

Though I thought most of the buildings at Glacier were luxurious and perhaps unnecessary, I completely took for granted the services they offered, from efficient indoor plumbing to ranger stations with interpretative signs to the park’s basic cleanliness. Today, most large national parks operate like small cities, each with their own infrastructure, governing body and workforce. This design was intentional, and the initiative that created it was arguably the largest program the National Park Service has and will ever oversee. The program, Mission 66, provided funding for buildings and infrastructure that created the National Park System as we know it today.

The Mission 66 Program

Perhaps in reaction to two decades of neglect prior to World War II, one of the defining characteristics of the post-war period was the abundance of federally funded infrastructure initiatives. A National Park Service infrastructure update was one such project. Between 1931 and 1949, national park visitation rates went from 3.5 million to 30 million as a result of Americans’ increased mobility, an emerging middle-class and a growing appreciation for outdoor recreation, among other things, but the federal government had not done much to maintain the park sites and facilities.

Photograph of an unidentified man standing next to an automobile on a dirt road on the edge of a mesa, possibly in Mesa Verde National Park. Photographed by George L. Beam in 1929.

In 1949, National Park Service Director Newton Drury argued that modern facilities could conserve park land by limiting public impact on fragile natural areas. A public survey conducted by the Park Service revealed the need for overnight accommodations and interpretive resources. Mission 66 would elevate the parks to a modern standard of comfort and efficiency as well as attempt to conserve natural resources.

According to Sarah Allaback’s history of Mission 66 visitor centers, during the summer of 1954, Department of the Interior Undersecretary Ralph Tudor began a reorganization that allowed then-Park Service Director Conrad Wirth to focus his attention on the subjective and procedural problems that plagued the Park Service. Wirth’s solution hinged on changing the way his budget was structured. Wirth asked Congress for, and received, an entire decade’s worth of funding, which provided the Park Service with money to sustain building projects over many years. The program would conveniently culminate in a celebration of the Park Service’s golden anniversary in 1966.

A 1956 issue of Architectural Record proclaimed that Mission 66 would produce “simple contemporary buildings that perform their assigned function and respect their environment.” Modern architecture expressed progress, efficiency, health and innovation—values the Park Service hoped to embody over the decade. Mission 66 was praised as a program that would boost the conservation movement and inspire the country to develop long-range projects for natural and cultural preservation.

1968: Mission 66 comes to Mesa Verde National Park

The Far View Visitor Center at Mesa Verde National Park is an example of the Mission 66 style of modern architecture.

Dedicated in 1968, Mesa Verde’s Far View Visitor Center was one of the last Mission 66 visitor centers to be opened. Designed in 1964 by Joseph and Louise Marlowe and the Western Office of Design and Construction, its architecture is notable and noticeable. The cylindrical shape was made using brown brick construction and was meant to evoke a kiva, or a Pueblo ceremonial structure. Originally named the Navajo Hill Visitor Center, the name was later changed to Far View after the spectacular view of the park that a visitor could take in from the observation deck at the rear of the structure.

Unfortunately, Far View did a poor job of meeting Mesa Verde’s growing needs. Not only is it far from the park entrance in a location that’s at risk for wildfires, but it’s also not designed to store artifacts gleaned from archaeological research at the park; the facility had never been intended for much more than an interpretive space with exhibits. A new visitor center and research facility was completed at Mesa Verde in 2012 to greet a new generation of park visitors and fulfill the evolving role of the modern visitor center.

According to a 2012 article in the Cortez Journal about the grand opening of the new visitor center, Mesa Verde intended to continue the maintenance and plumbing at Far View and keep the electricity running to save the building from decay; however, the Park Service released no plans for reuse, and today the building still sits stagnant and out of use.

Evaluating Mission 66

Completed in 1967, the Beaver Creek Visitor Center in Rocky Mountain National Park was a Mission 66 project.

It can be difficult to point to just one metric to measure the success of the Mission 66 program. The program’s success must be evaluated from multiple angles, including from the perspective of the Park Service itself against the metrics it designed for the program. Mission 66 visitor centers did arguably streamline the National Park experience and make the parks’ natural beauty more accessible through improved infrastructure, services and interpretation. But this success breaks down a bit when we analyze the program from a long-term point of view, from which we can see that over the past sixty years, budget cuts made it difficult for some parks to provide the building maintenance and staffing that was necessary to creating the intended visitor experience.

Park Superintendent Jesse Nusbaum (center) tending a campfire at Mesa Verde National Park with Eric O'Brian (left) and wife Aileen Nusbaum (right) with a dog. The photograph was taken by George Lytle Beam, circa 1924

The notion of success breaks down even further when considered from the viewpoint of a modern environmentalist. While improved infrastructure and staffing made national parks cleaner, the accessibility it enabled encouraged a volume of visitors not anticipated by park officials. Many large national parks see heavy traffic and crowded campsites. Conversely, other national parks suffer from a decreasing visitorship and are at risk of being closed. Admittedly, many factors contribute to park visitorship. Nonetheless, it is important for us to recognize that both the way the public experiences the parks and the capacity of the parks to accommodate the public can be traced back to the Mission 66 program.

Mission 66 visitor centers are visual representations of a paradigm shift in the National Park Service that took place in the 1950s and 1960s; they symbolize the ambitious drive to standardize the national park experience and make the parks more accessible. The legacy of Far View is an example of the unique way places and structures represent the stories and collective memory of American culture.

Preserving Place

Just because Mission 66 wasn’t overwhelmingly successful doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be remembered. It goes without saying that recounting the history of the Mission 66 program—however fraught with delays, budget cuts, ambition and controversy— starts a conversation about decision-making and critical thinking that can apply to our historic resources today. Unfortunately, the best visual representations of that history are at risk. Some of the visitor centers constructed under Mission 66 have not been maintained or can no longer serve the high number of visitors, programs and functions for national parks. Most of these centers have reached their fiftieth year, making them eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. However, instead of preserving them and treasuring the heritage they represent, park officials are deciding to phase out, tear down or demolish these historic centers. Rendering the buildings obsolete is a tempting way out of rehabilitating these structures for sustainable reuse, but doing so also erases an important part of national park history and our collective memory.

The Dinosaur National Monument Visitor Center closed in 2006 after being plagued by more than 50 years of deficiencies resulting from bentonite in the soil composition beneath the structure.

Park officials encounter difficult decisions about maintenance on a daily basis, but conversations with visitors, volunteers and officials reveal one constant factor: no one takes for granted the resources and opportunities that national parks provide, and everyone is concerned about their protection. The future of the parks depends on a call to action to educate the public about the condition of the parks’ historic resources and how we can support their sustainable reuse. I urge you to contact to your local, state and national representatives to let them know that these parks and their environments, both built and natural, are important to you. For many national park enthusiasts, erasing a part of park history is not an option, even if Mission 66 lacked flawless execution or foresight. Just because a visitor center has not been maintained does not mean it, or the history it represents, is obsolete.

The new visitor center and quarry exhibit at Dinosaur National Monument opened in the fall of 2011 after being closed for a five-year rehabilitation.

A Logical Legacy

As a historic preservationist, I believe our first priority is saving these buildings for rehabilitation. Not only are they a valuable part of the history and memory of Mission 66 and modern architecture, they are actually still standing. When looking at cost and economic benefits alone, rehabilitating these structures instead of demolishing them is a logical solution.

According to the Economic Power of Heritage and Place, a 2011 study of the economic benefits of historic preservation projects in Colorado, preserving historic structures and landscapes has direct economic benefits, from creating jobs to strengthening heritage tourism. A 2011 study by the National Trust for Historic Preservation revealed that heritage tourists on average spend $994 per trip, compared to $611 per trip for all US travelers. In Colorado, 50 percent of travelers are heritage tourists.

Designed by the modernist architect Richard Neutra and his partner Robert Alexander, the visitor center at the Gettysburg National Military Park housed a 360-degree cyclorama painting of the battle at Gettysburg by the French artist Paul Philippoteaux. Named after the painting, the Cyclorama building was a deemed cutting edge when it opened in 1962.

One of the most environmentally friendly development practices is the decision to repair and reuse an existing building, rather than replace it, especially when considering the overall life-cycle cost and energy use of the building. The National Trust study stated that the cost of a rehabilitation project is roughly the same, if not less, than new construction and that approximately 25 percent of materials being added to landfills is demolition and construction waste.

There are benefits other than cost savings to preserving historic Mission 66 visitor centers. If you have ever sought out specialized location-based activities or visited a historic place on a vacation, you have engaged in heritage tourism and likely value activities that authentically represent the stories and people of the past and present. Mission 66 structures and centers are tangible contributions to a more complete understanding of our story as a recreating nation, not to mention that their modern design is funky, unusual, fun and elicits that perfect amount of nostalgia and familiarity.

Government officials decided to raze the Cyclorama in 2013 in order to rehabilitate the landscape to its bucolic, 1860s state to best meet the park objectives of protecting and preserving cultural and natural resources.

Preserving Mission 66 visitor centers is a logical, tangible and unique way of presenting and interpreting the story of one of the nation’s most ambitious and ubiquitous projects. They represent both the optimism and turbulence of a nation on the verge of tremendous change. Why demolish our legacy when we can celebrate and learn from its complexity?