Story

The Role of Toys in the Archaeology of Self

In early 2008 I visited my childhood home in North Carolina with my wife Laurie and oldest son Andrew. Laurie was pregnant with our younger son James. Having children was already making me feel nostalgic about my own childhood, but something else emphasized it on that visit.

Recently a bad rainstorm had washed out a large area of topsoil in the backyard. As an archaeologist, I always seem to be looking at the ground for artifacts, and one evening after dinner, I noticed something sticking up out of the ground. It was grey, green, and black plastic and looked somehow strangely familiar. Upon closer inspection, I realized it was the partially exposed forward portion of a model plane— a British jet bomber called the Avro Vulcan, to be specific. Almost instantly, memories from more than thirty years past came flooding back to me. I had buried the model plane myself sometime during the mid-1970s, and something in my memory told me there was more to be found.

I quickly spotted a few more items, and of course, the first thing I wanted to do was excavate. I humorously suggested to my parents that I was going to conduct a formal excavation in their backyard, to which they promptly replied “no way!” So I settled for quickly digging up what I could see. I ended up recovering the remains of more than a dozen plastic model toys. It was a scale model graveyard of ships, planes, cars, and spacecraft.

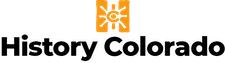

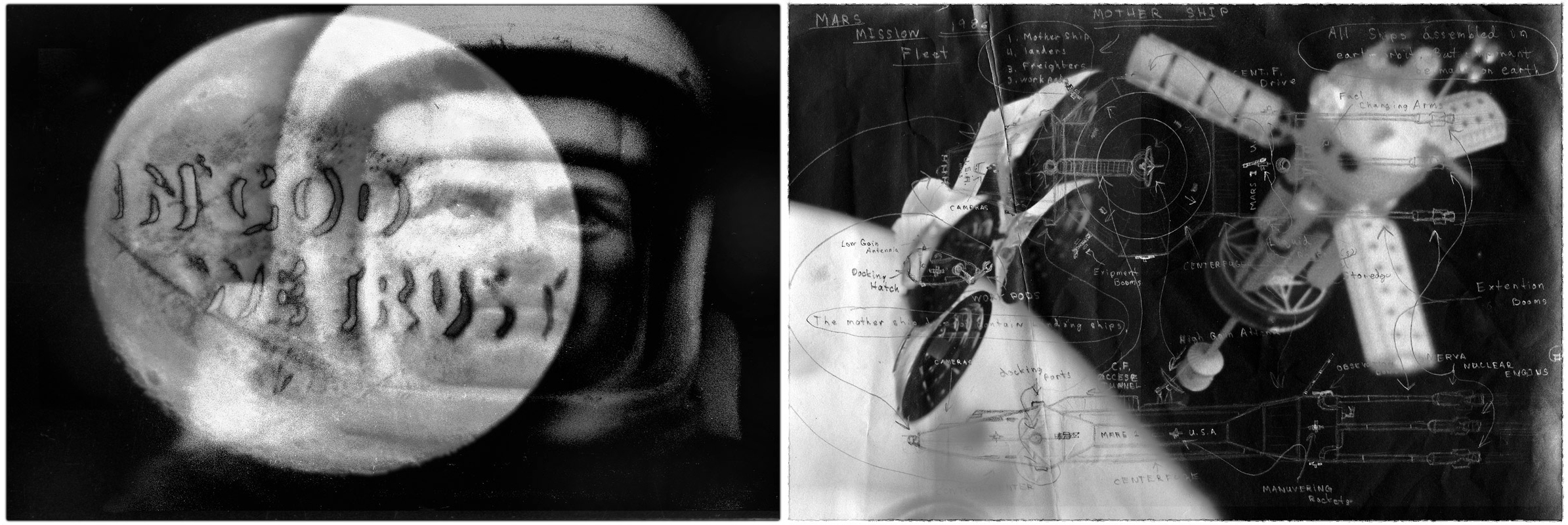

Later I found another collection of models and old toys in my parents’ attic. These were the ones that I had saved and were kept in my room until my parents redecorated. I photographed each item as I excavated the site (read: as I explored the attic), but I didn’t photograph the items in a technical fashion, as my archaeologist self would. These discoveries appealed more to my artistic side, so I photographed them in a documentary fashion. I titled the series of photographs “Fragments of the Past”.

It was a fun and fascinating process, and it raised many questions about my childhood. Why had I done this? Was there some long-term intent? And why hadn’t I given it any thought over the past three decades? Interestingly, I found the answers by looking into a relatively new branch of anthropological study called the archaeology of self as well as examining a study of toy artifacts from archaeological sites and learning what they can tell us about childhood’s role in society.

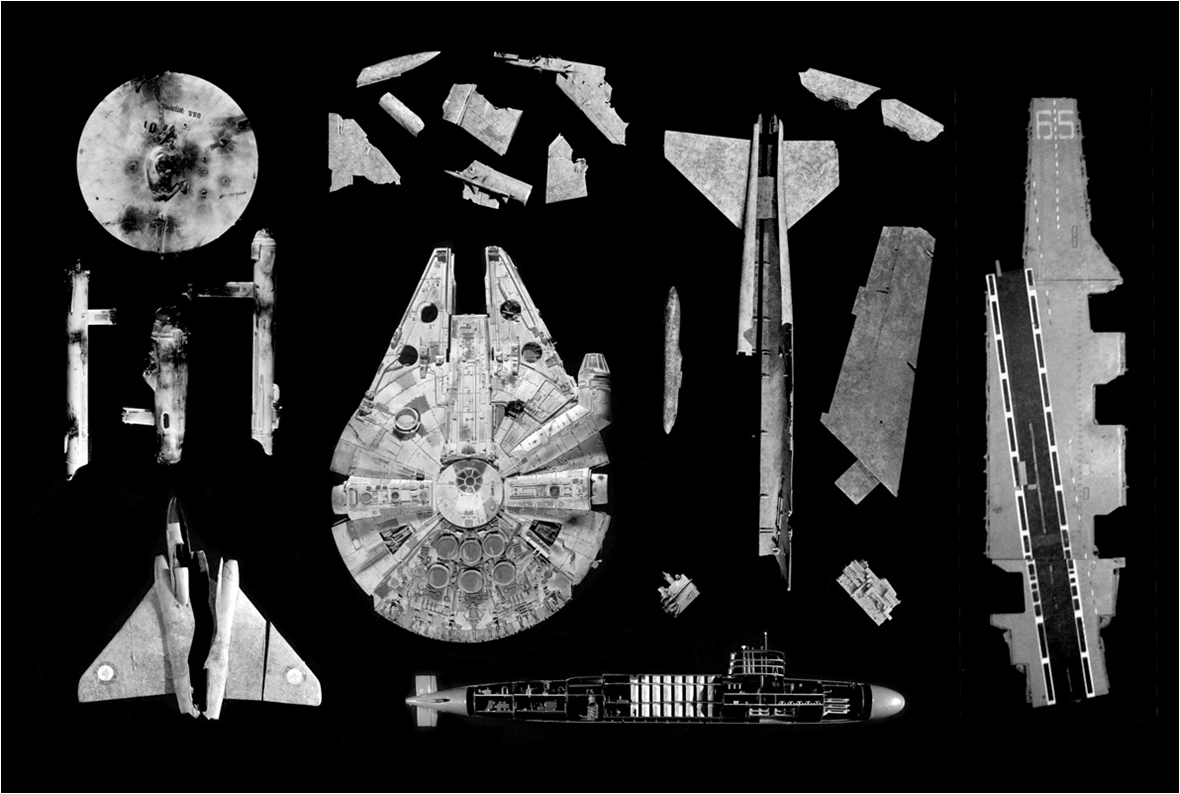

So how does my personal story connect to Colorado archaeology? The answer lies in a historical archaeology project at the Grenada War Relocation Center in southeastern Colorado, which started in 2008 and was led by Professor Bonnie Clark from the University of Denver. More commonly referred to as Amache, Granada Relocation Center was one of ten World War II relocation camps where thousands of American citizens of Japanese descent were interned throughout the course of the war. In the summer of 1942, entire families from the West Coast were required to collect a handful of belongings, give up their homes, and move to an internment camp. Hundreds of children were included in this forced relocation, and many called Amache home for the three years.

After the war, most of the buildings at Amache were dismantled or moved, but the overall site was basically left alone, and this isolation protected the archaeological integrity of the site. The site was surveyed and mapped in 2003 with funding from a History Colorado State Historical Fund grant and designated as a National Historic Landmark in 2006. Since 2009 History Colorado has helped support Dr. Clark’s research at Amache with State Historical Fund grants. While all aspects of Dr. Clark’s research is intriguing, one of the most fascinating and relevant discoveries was her identification of artifacts associated with children. Additionally, Dr. Clark consulted former Amache internees as part of her research efforts. Because the internment program occurred more than seventy years ago, today the only living survivors are those who were children when they lived at Amache.

Fragment of a toy truck (1) and a complete example from another collection (2)

DU graduate student April Kamp-Whittaker focused her thesis on the topic of childhood at Amache, and in 2009 her work resulted in an exhibit at the University of Denver Museum of Anthropology titled, “Through the Eyes of a Child”. The exhibit featured artifacts associated with childhood activities, such as household chores, games, and toys. Through their studies, DU researchers found that while the conditions at Amache were very disruptive and different from their traditional Japanese American lives, families strived to maintain a degree of normalcy—especially for their children. Former internees told the researchers that because of the extremely cramped living facilities, children were encouraged to play outside, with boys wandering further from home than girls. Former internees shared stories about how they had to leave most of their belongings behind, including most of their toys. But some may have brought toys with them; at the site, archaeologists found a fragment of a plastic truck that was only manufactured prior to WWII, suggesting the possibility that it had been brought to Amache by a child. How cherished must that toy have been to have been included in the one suitcase of belongings allowed?

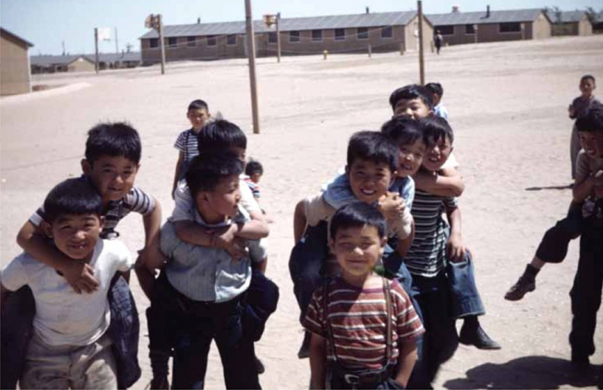

Marble games were also popular, and many lost marbles were found during the excavations. Other toy artifacts that were found include a Disney Mini Mouse charm, a rubber ball, fragments from a Depression glass tea set, and glass candy containers in the shapes of military planes, tanks, and ships. Archaeologists even found evidence of a scale model building in the form of plastic parts and a glass bottle of modeling glue. The presence of so many war-related toy artifacts reinforces the historical narrative that suggests that internees generally supported the US war effort and went to great lengths to show their patriotism. A good number of toy artifacts were found in the excavations at the site, and the overall distribution of traditional boy toys versus traditional girl toys reinforced the idea that boys tended to play farther away from home than girls. This brings me back to the question of what toy artifacts can tell us about childhood roles.

Archaeologists and anthropologists have suggested that in traditional cultures, toys represent a gender-specific type of miniature role playing. It can easily be argued that Japanese Americans still maintained something of a formal tradition pertaining to family roles, with girls playing with domestic activity-themed toys and boys often playing with war-themed toys. But while this reflects some degree of structure, it is generally seen as random and unpredictable in the archaeological record and does not affect the formation of sites in a deeply meaningful way.

Some anthropologists, such as Laurie Wilkie, suggest that toys are more than analogous ways to introduce children to adult roles. She proposes that toys become “contentious objects in dialogs of control and resistance.” Her research on Southern plantations suggests that children were acting independently of their parents in the creation of their own special places. Indeed, this type of behavior would very likely manifest itself in the archaeological record. Her suggestion brings me back full circle to my personal archaeology of self as evidenced by the scale model graveyard in the backyard of my parent’s home, and it puts me in a unique position for drawing conclusions.

Since I am at the same time the child who created the artifacts and the archaeologist who is trying to understand what they mean, I can tell you that I was in fact doing exactly what Wilkie suggests: I was creating an imaginary place where all of these different scale models came together to participate in battles and stories in my mind. These battles often involved destruction that was absolutely not allowed in my home—battleships and starships on fire and exploding, planes and cars crashing from the roof tops, giant boulders crushing unsuspecting vehicles. Thinking back, I realize this was clearly a form of childish recklessness and protest. I was the good child—I was the one who never disobeyed my parents!—and yet I was the one who blew things up.

Fortunately, in the long run I clearly favor creative energy over destruction, as evidenced by my academic and artistic efforts. In addition to being an archaeologist, I am also a trained artist and photographer, and I’ve spent much of my career trying to examine archaeology from both scientific and artistic perspectives. Finding these “artifacts” from my own youth prompted me to delve deeper into my own past, to conduct archaeology on myself. I especially wanted to explore my artwork from the same time period as the buried artifacts. Luckily, I had saved many of my old negatives and drawings from the 1970s and ‘80s. I began digitally scanning them and thinking about what I had intended for them when I was young. I realized that I had high ideals for what they represented as creative expressions of science fiction, horror, and fantasy from literature and film, but at the time I was unable to fully realize them given my limited skills and the technological limitations of the era.

In the summer of 2008 our son James was born. He was healthy but also had colic and kept us awake many nights. I would pass a lot of that time looking at my old artwork, and as I examined it, I began to visualize better realized expressions of the youthful efforts I had sought. By 2010 I had created a series of black and white collages that combined many of the photographs and drawings. I titled the series “Excavating Childhood” and started showing my work at galleries in Denver. The series represents a synthesis of my youthful artistic intent as well as my nostalgia looking back as an adult—or at least, this is the impression I hope they convey. Being informed by this archaeological look at myself and a photographic journey to document remnants of my childhood has made me excited to see how my two boys will experience toys and what lessons they will carry with them as they grow up. I haven’t noticed them burying anything yet, but I do find Indiana Jones Lego all over the place.

Want to learn more about the archaeology of self? Other archaeologists and anthropologists have pursued these types of personal studies through the forms of fiction novels, historical documentary, sculpture, and more. Examples include forensic anthropologist Kathy Reichs’ fiction novels and British archaeologist Christine Finn’s Leave Home Stay project about her family’s seaside home in Deal, Kent. Similarly, creative artists have turned themselves into anthropologists to study topics relating to childhood and nostalgia. Check out Fred Pirone’s Archaeology of Self project and Beverly Moxon’s Childhood Archaeology project for some strong examples. A good scholarly text on this topic is Ancient Muses: Archaeology and the Arts edited by John H. Jameson, Jr., and a good popular book on the topic of self archaeology is Keri Smith’s How to be an Explorer of the World: Portable ArtLife Museum.