Story

In Starkville, a Small Certified Local Government with Big Hopes

Sitting deep in southern Colorado, the former mining town of Starkville—like so many other mining communities—has seen its share of booms and busts. Although the town is far smaller than it was during its once-lively and industrious mining period, the people of Starkville see their past as something worth preserving. They recently formed a CLG—a Certified Local Government—to help them preserve the town’s remaining historic buildings.

Certified Local Governments are recognized by the National Park Service, and enable local communities to gain access to preservation tools like tax credits and grants. These tools can help communities keep their historic buildings standing and in use for future generations.

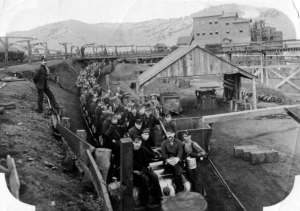

Founded in 1865 as San Pedro but later renamed for a local mine owner, Starkville was once a coal camp for a succession of mining industry companies. In 1896, Colorado Fuel & Iron (CF&I) leased the mine from the Santa Fe railroad. CF&I’s holdings and operations were a strong industrial and economic presence that stretched across Colorado, and the company was responsible for operating many mines and camps. At one time, the company employed more people in Colorado than any other organization.

Throughout this rich mining period of the late 1800s and early 1900s, Starkville boasted a thriving population. Thanks to CF&I’s operations there, the camp—which became a town—was an important site of economic and labor activity. Throughout the West, mills and smelters were fueled by coal drawn from Starkville’s mines and coke ovens.

Although mining camps and towns could see a lot of turnover in their population, the community in Starkville was stable enough that it required a school for the children of the workers.

“We have a school house project here, built in 1881. It’s a stone building. It was in use up until 1965,” Starkville Mayor Crick Carlisle said. Central Starkville School served the community’s kindergarten through eighth-grade students, including the children of the laborers during the town’s busy mining period. It’s this building that’s currently the focus of the Starkville CLG’s preservation efforts.

Although the coal industry brought economic opportunity here, it also brought disaster and controversy. Throughout the years, Starkville was often the site of labor disputes and the struggle between organized labor and corporate mining interests.

As early as 1881, Starkville miners were striking to gain an increase in wages. In May of 1884, the miners went on strike again in solidarity with their fellow workers of the Knights of Labor. This attempt met with failure, however, as they broke the strike and received a reduction in pay. In April of 1894, Starkville miners joined the nationwide Marching Strike in order to secure living wages and improve working conditions in the mines. Eventually the miners agreed to return to work, but without winning any concessions.

Such protests and strikes were not uncommon at the time, as workers organized and began to assert their political and social influence to improve their situations.

Starkville was no stranger to disaster, either. In 1888, an explosion at the mine sent logs flying high into the air. Only two men were killed, but many more could have died. That deadly potential was realized twenty-two years later.

On October 8, 1910, the mine exploded when a spark from a short circuit ignited the ever-present coal dust in the air. Fifty-six miners lost their lives in the tragedy. The explosion wasn’t the only danger. “Afterdamp” is a deadly combination of gas and dust that is essentially a blanket of carbon monoxide. When rescuers opened up parts of the mine that had been cut off in the blast, they found bodies surrounded by empty pails. As the miners had waited for rescue, they sat down to eat a meal. One by one, they died from the effects of the afterdamp.

In the following years, mining operations began to draw down—so too did Starkville’s population.

“At one point in time we had 3,000 people in Starkville,” Mayor Carlisle said. “But now we’re down to about 100.” Official census numbers put the population at even less than that.

“When I came into office, we had $0 in our bank account. There was talk of disbanding the local government and going back to county control.”

Mayor Carlisle wanted to find opportunity for the future of Starkville. After attending a preservation “roundtable” event sponsored by History Colorado, he realized that opportunity lay within Starkville’s historic resources.

At the roundtable event, he learned about the economic opportunities and incentives for historic preservation, such as tax credits for work on historic properties, getting historic properties listed in the State or National Register of Historic Places, grants from the State Historical Fund, and more.

“We were advised that a CLG was the shortest path to get more funding. We could apply for funds from more foundations.” Those funds could go to revitalizing the historic buildings that Starkville still possesses.

After Starkville earned its Certified Local Government status and recognition from the National Park Service, Mayor Carlisle and other volunteers began to take steps to preserve their most prominent resource—the Central Starkville School building.

The Starkville CLG applied for and received a grant from History Colorado’s State Historical Fund in order to conduct a Historic Structure Assessment, or HSA, to evaluate the physical condition of the school. A Colorado-licensed architect and/or a structural engineer, working in consultation with a historic preservation specialist, conducts the HSA to help determine what restoration and maintenance is appropriate for a historic property. They completed the HSA of the school, and also received $40,000 from the Department of Local Affairs to conduct a feasibility study. Now, with construction documents, a technical manual, and a set of architectural plans in-hand, the Starkville’s CLG—and the people of Starkville—are one step closer to saving their school building.

Although Starkville’s built environment may not be extensive, Mayor Carlisle wanted to form the CLG to give his community the opportunity to save what it still had. “We tried to set up our CLG so that people with homes that were fifty years old or older had the opportunity to try and get them designated as historic.”

Another treasure from the town’s mining past might be next.

“When I found out we could get an acquisition grant [through the State Historical Fund], we looked at the possibility of acquiring the old mining assayer’s office,” Mayor Carlisle said. “The building had something to do with the mining company. It’s a very interesting building made out of stone that we’d like to save from dying.”

The people of Starkville have proven that, no matter how small a community may be, its history is still worth preserving.