Story

Mace's Hole: A History of Bandits, Brigands, and Beulah

Beulah is a small town in Pueblo County, nestled into the foothills of the Wet Mountains. It inhabits a quiet, tranquil, and picturesque valley. But for decades during the 1800s, this otherwise idyllic valley wasn’t known for its gorgeous mountain views, its peaceful woods, or rushing creeks. Instead, it was notorious throughout the state as a hideout for bandits.

The Legend of Juan Mace

Beulah Valley is relatively isolated. Until the highway carved a path through the hills, the only accessible entrance was through a narrow pass on the eastern end of the valley. This made entry difficult for large groups, and the pass was easily defended from the inside. But it also had easy access to the plains, and is very near several important locations: the Arkansas River is only a short ways away, and during the 1800s the main road along the Front Range passed not far from the mouth of the valley. All of this combined to make it an almost ideal location for banditry.

The first, and possibly the most famous, of these outlaws was a Mexican national who for decades lent his name to the area: Juan Mace.

Mace (or, possibly, Maes or Mez) is an enigmatic figure from the earliest days of Colorado’s colonial history. He inhabited the Beulah area as early as the 1840s, likely arriving around the same time as the construction of El Pueblo trading post.

During that time there was little in the way of settlement in Colorado. Ranches were only starting to crop up on either side of the Arkansas River, and they were isolated, far from population centers in either the United States or Mexico (which until 1848 controlled all of southern Colorado). This made them easy, and frequent, prey for bandits.

Juan Mace was one of the earliest outlaws in the territory, and he quickly became notorious after making his home in the peaceful glen now known as Beulah Valley. At the time settlers in the area had a different name for it: Mace’s Hole.

The idyllic Beulah Valley, photographed from the south. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Other than his name and his notoriety for cattle theft, very little is known about Mace. Some accounts say he worked alone, others say one or two sons accompanied him; yet others claim he had a cadre of accomplices numbering 500 or more. Tales recount his exploits, including how he tricked American ranchers, used local trees for target practice, or even participated in the tragedy that befell El Pueblo in 1854 either as attacker or defender. These stories are all varied and colorful, but also impossible to verify.

Juan Mace likely only occupied the valley for a short period. Though he left a significant mark on the region and remained a popular figure in local legend for generations, he had vacated the area at some point before 1860.

Some accounts say that he was eventually captured by the ranchers and hanged for his crimes, others claim that he went south to New Mexico, where he continued his banditry through the 1870s. “Uncle Dick” Wootton, famous Colorado mountain man, claimed that Juan Mace was one of the men who died when El Pueblo trading post was attacked in 1854 (which is almost certainly untrue).

Whatever the reason, Juan Mace was gone by 1860—but the valley didn’t stay uninhabited for long. That year, a different renegade group came to the area: the Confederate Army.

Colorado’s Civil War

The Civil War erupted scarcely a year after the Pikes Peak Gold Rush brought tens of thousands of settlers to the Rocky Mountains in search of the precious metal. Though it was still sparsely populated, the mineral wealth of the region was on the mind of both Union and Confederate strategic thinkers. Trade in precious metals could go a long way toward financing the war effort of either side, so control of the gold fields was imperative.

Almost all of the residents of the newly minted Colorado Territory came during the initial gold rush, and many of them had emigrated from the southern states. In The Colorado Volunteers in the Civil War, author William Whitford explains that the first territorial governor, William Gilpin, estimated that one in three residents of Denver was a Confederate sympathizer.

For these reasons, both sides were quick to mobilize troops in the rural frontiers of Colorado. The Union army had the advantage, as it controlled the territorial capitol of Denver as well as the major forts of the area—particularly Fort Garland, which defended entry into the region from Confederate-controlled New Mexico.

Eventually a Confederate army would attempt to breach Colorado from the south, leading to the famous battle of Glorieta Pass, but the first Confederate incursions into the territory were of a much more subtle nature.

“Action at Apache Canyon” by Domenick d’Andrea depicts Union soldiers charging through the canyon during the famous and consequential Battle of Glorieta Pass.

In or around 1860 a certain Colonel John Heffiner was tasked with gathering volunteers and recruits from among the Colorado populace, for the purpose of damaging the forts’ supply lines and eventually participating in attacks on Fort Garland.

For his base of operation, Heffiner chose Mace’s Hole.

Just like Mace before him, Heffiner found that the valley was perfect for his predatory purposes. It was secluded, easy to defend, but could easily infringe on travel between Colorado City to the north and Fort Garland to the south. This was especially useful because they had received orders from General Henry Sibley to disrupt mail service, assault Union supply trains, and attack the gold fields.

These Confederate irregulars occupied the valley for a short while. More than 600 of them had gathered by the summer of 1861, forming a significant encampment. They successfully escaped notice for some time, thanks in part to the assistance of Alexander Hicklin, a local rancher also known by his nicknames “Ole Zan” and “Ole Sessesh” (for “secession”). Hicklin provided services and supplies to the Confederates, all the while passing along misinformation to the Union troops at Fort Garland. He worked to sabotage the federal troops however he could, and even eventually defrauded them of one thousand dollars for “illegally seized cattle,” but he was never convicted of any crimes or even brought under suspicion for Confederate sympathies.

However, despite this local assistance and their rapid mustering, they were never able to carry out their mission to any significant degree. By October the Union army learned of their presence and set out to intervene.

Union forces from Fort Garland began scouting Mace’s Hole that month, spooking many of the Confederate volunteers. Soon after, a battalion from Fort Lyon arrived and marched upon the valley. A large number of the Confederates fled into the surrounding hills once the federal troops entered the valley in force, but forty-four were captured and brought to Denver for imprisonment.

Among those taken were two brothers named James and John Reynolds, who would later go on to found and lead the notorious Reynolds Gang of Confederate guerillas. Through 1864 they terrorized the territory, attacked wagon trains, and plundered food, supplies, and gold in significant numbers. They eventually met their end after being defeated by Union troops, and James Reynolds was executed without trial at the orders of Colonel John Chivington.

With the end of that gang, the last outlaws of Mace’s Hole were dead. But their legacy lives on, somewhat to the chagrin of some later settlers.

Becoming Beulah

Immediately after the war, Mace’s Hole was largely uninhabited. In early 1865 there were only four residents of the valley, and none of them permanent: two American trappers named Almon Coburt and John Root, and two mysterious but unnamed figures whom the trappers reported to be the sons of Juan Mace. These supposed scofflaw’s sons did not linger in the valley for long; by the time the first family to settle in the area arrived in autumn of that year, the Mace brothers had left for parts unknown, and like their father vanished completely from history.

This state of affairs quickly changed over the next few years. The Arkansas River valley was fertile and well-located, and as Pueblo sprang up along the riverbanks outlying communities grew rapidly as well. By 1870, there was a small but thriving village in Mace’s Hole, prospering by providing cattle and lumber to Pueblo and other nearby towns. In 1871 a one-room schoolhouse was built, and in 1873 the Mace’s Hole Post Office was established.

The year 1876 was an important one for several reasons. It was the first centennial of the United States, it was the year Colorado became a state, and it was the year Mace’s Hole became Beulah.

According to local histories, resident Reverend Gaylord disliked that the settlement was named after an outlaw, and felt that the name “lacked beauty.” He successfully organized a vote to change the name, with several names possible on the ballot. The two most popular suggestions were “Silver Glen,” referring to the beauty and natural resources of the area, and “Beulah,” a reference to the biblical passage Isaiah 62:4. The latter won out by only two votes.

Though the name is gone, and despite the antipathy of Reverend Gaylord, the legacy of Mace’s Hole lives on in the memory and history of the town’s inhabitants. The legend of Juan Mace and the history of the valley as a brigands’ hideout remains a colorful and unique part of Colorado’s small-town past.

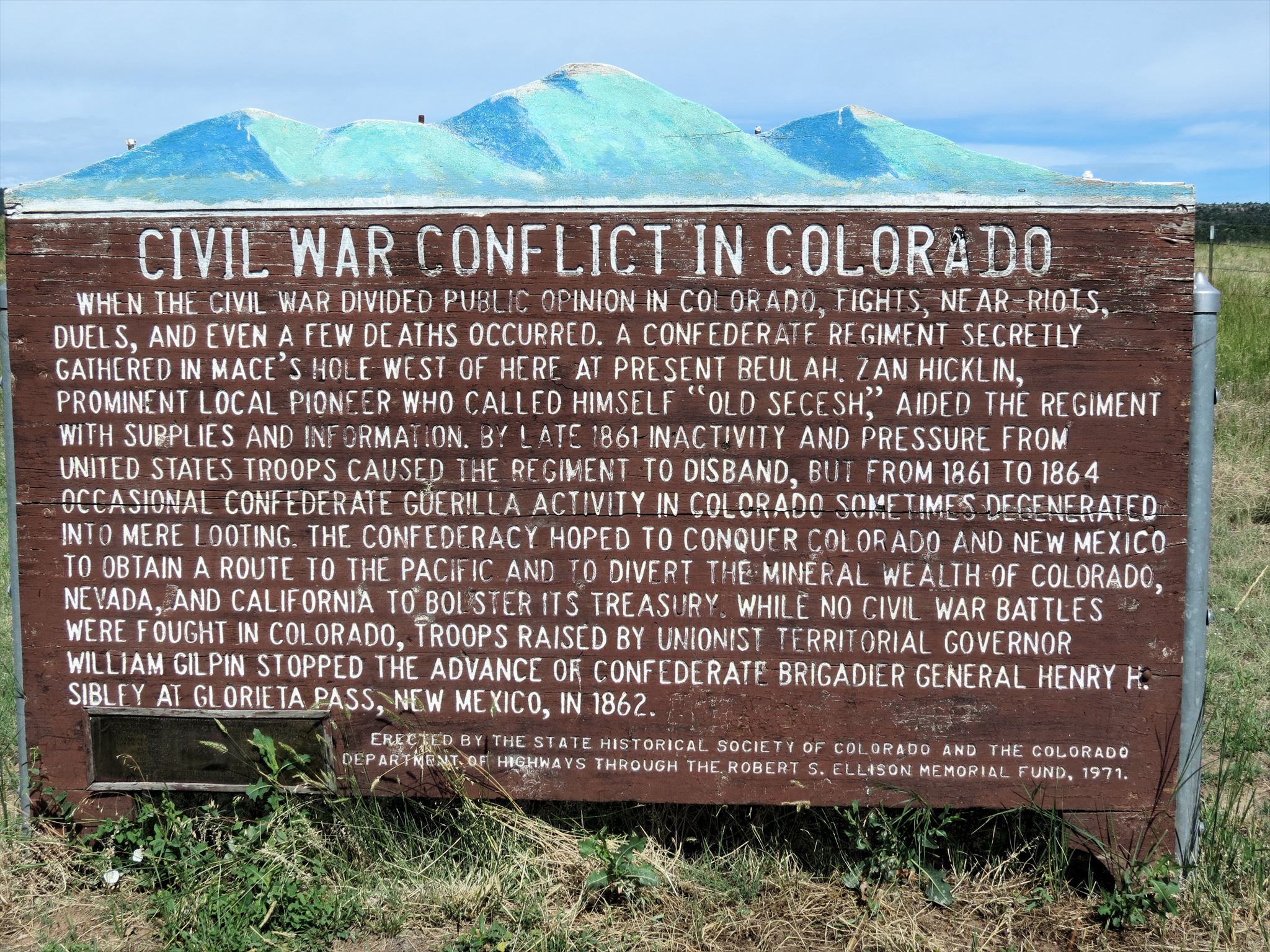

This roadside marker sits just outside the entrance to Beulah Valley / Mace’s Hole, and commemorates the activity in the area during the Civil War.

Sources:

From Mace’s Hole, the Way It Was, To Beulah, the Way It Is. Second Edition. Beulah: The Beulah Historical Society, 2000.

Bright, William. Colorado Place Names. Third Edition. Boulder: Johnson Books, 2004.

Conner, Daniel E. A Confederate in the Colorado Gold Fields. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970.

Cook, David L. and Cook, John W. Hands Up; or, Thirty-five Years of Detective Life in the Mountains and on the Plains. Denver: The W.F. Robinson Printing Co., 1897.

Whitford, William C. The Colorado Volunteers in the Civil War: The Battle of Glorieta Pass in New Mexico, March 1862. Second Edition. Glorieta: The Rio Grande Press, Inc., 1971.