Story

Letters Colorado’s Women’s Suffrage Leaders Probably Didn’t Want You to Read

The campaign for the women’s vote in Colorado was one of letters. Organizers traded views and information regularly in private letters. Many of those letters are now in History Colorado’s collection, offering us a behind-the-scenes look at the campaign - even a few things they might not have wished to preserve for posterity.

One of the benefits of digging in the archives is that you get to read other people’s mail.

Emails and social media posts have become our primary way to communicate with the world. People in the past were just as snarky, shy, and judgmental as we are—they just communicated by slower means. Political and business leaders were as concerned that their “real” views would get out, and spin doctors and media savvy people were called in when something went wrong. When this happens in today’s world, the Twitterverse blows up and careers are made or ruined in the space of 280 characters. In the pre-internet world of letters, a cutting remark was as likely to result in hurt feelings, but unless someone leaked it to the newspapers, it was generally just a personal beef between enemies.

Ellis Meredith, an up and coming reporter, author, and the Corresponding Secretary of the Colorado Equal Suffrage Association during the 1893 Colorado women’s suffrage campaign, shared her papers with History Colorado in 1925. She gathered and curated these letters so that future generations could understand the campaign and the events surrounding it. She just didn’t know how similar they would still be to our present political online discussions.

You will notice in some of the entries below that the letters are addressed to Mrs. Stansbury. In her professional writing life she was always Ellis Meredith, even though in her personal life she may have used her married name. Yet another example of women’s shifting identities in a political and social world.

You can read each of the full letters below by following the link in the photo caption and downloading the pdf file from the bottom of the catalog record.

Politics Has Always Been About Who You Know (Especially Your Dad)

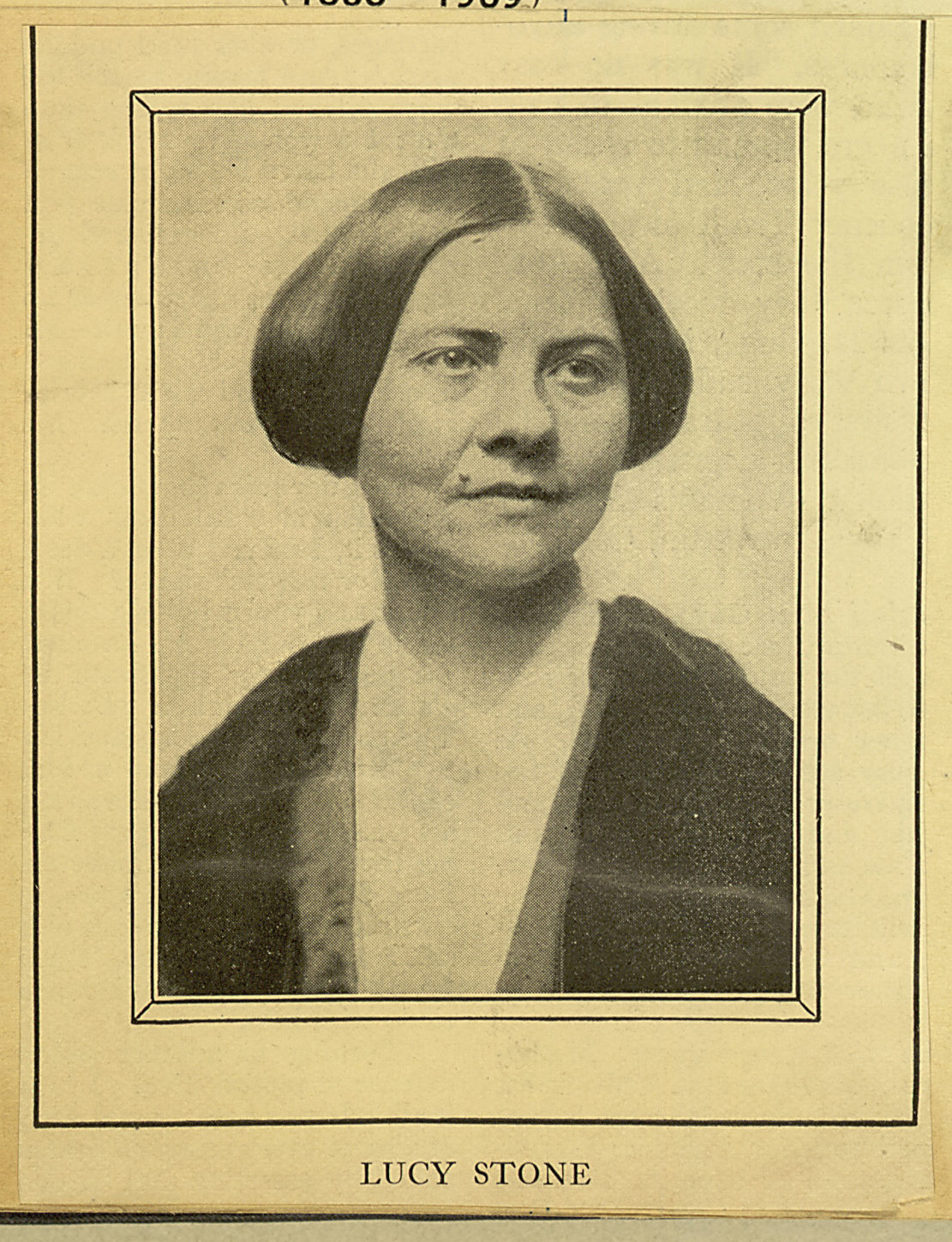

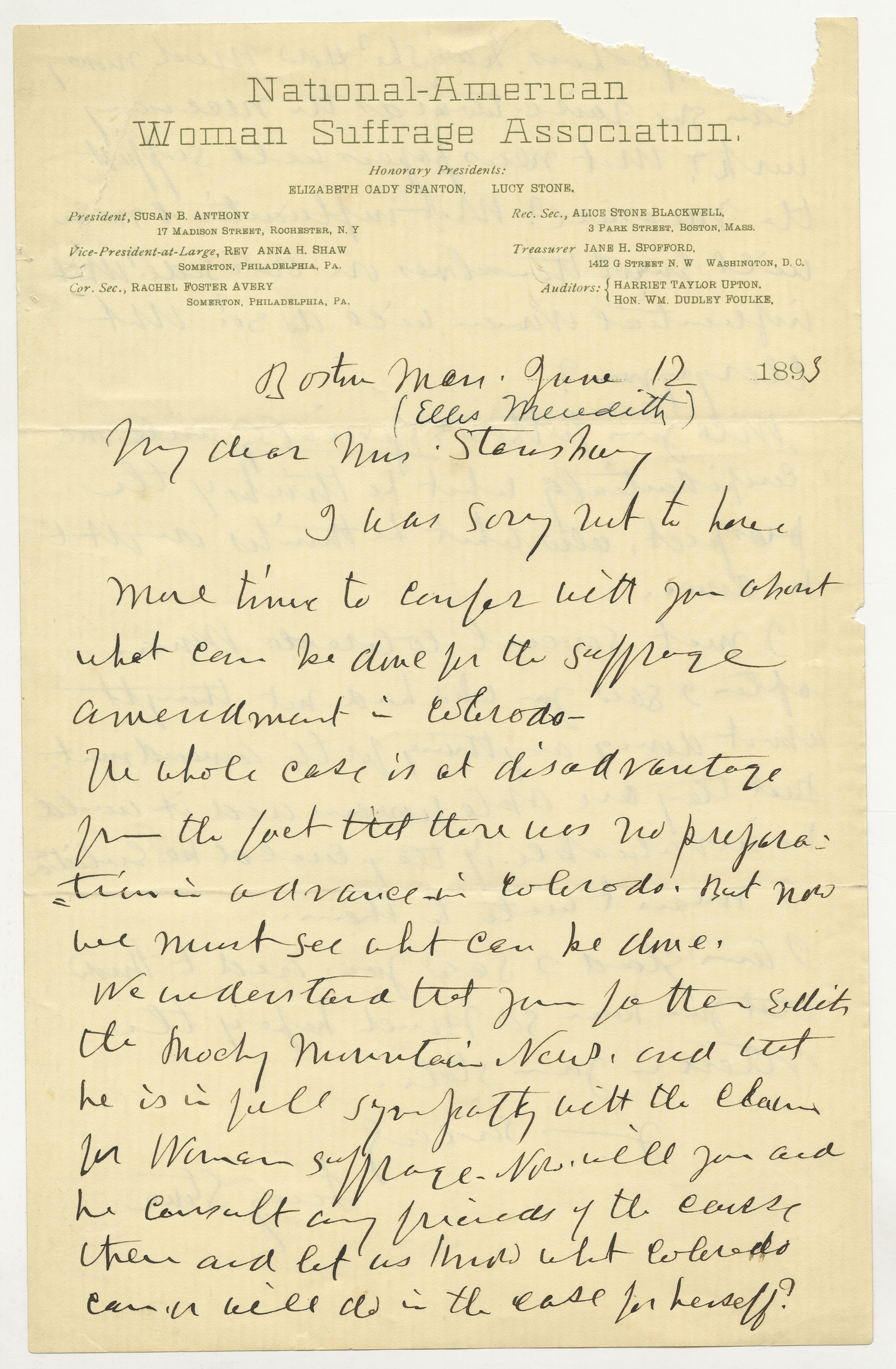

June 12, 1893 - Lucy Stone to Ellis Meredith

When Colorado suffragists started working toward putting women’s voting rights on the November 1893 ballot they contacted some national leaders for help. One of them, Lucy Stone, wrote back in June of 1893. The letter to Ellis Meredith was probably written after Stone and Meredith met at the World’s Fair in Chicago. This event seemed to be the kickoff to the campaign, as organizers had been working behind the scenes through their social networks but didn’t want to alert the anti-suffrage forces, particularly the brewing industry, to their plans. The breweries were often opposed to women’s suffrage because of many ties to the Women’s Christian Temperance Union—something Ellis and the Colorado suffragists were wary of, but also willing to use.

After assessing that the campaign was at a disadvantage because the groundwork had not been laid in advance, Stone asked Ellis if her father had any advice for the campaign because he was the editor of the Rocky Mountain News, one of the leading newspapers in Colorado. Stone also said that there were some women who she met that were not yet participating in the suffrage campaign, but that she would write to them to ask for their help.

Here’s an excerpt of the transcript:

Boston Mass. June 12 1895 - My dear Mrs. Stansbury, I was sorry not to have more time to confer with you about what [should] be done for the suffrage amendment in Colorado. The whole case is at a disadvantage from the fact that there was no preparation in advance in Colorado. But now we must see what can be done. We understand that your father edits the Rocky Mountain News, and that he is in full sympathy with the cause for Woman suffrage. [--] will you and he consult any friends of the cause then and let us know what Colorado can and will do in the case for herself?”...

Will your father especially write me confidentially what he thinks of the prospect, also what he thinks ought be done.

I am glad I saw you... [and] that you have so much hope of the voters in your state. Yours Sincerely, Lucy Stone

“Probably you will think us Maniacs” (Snark Never Goes Out of Style)

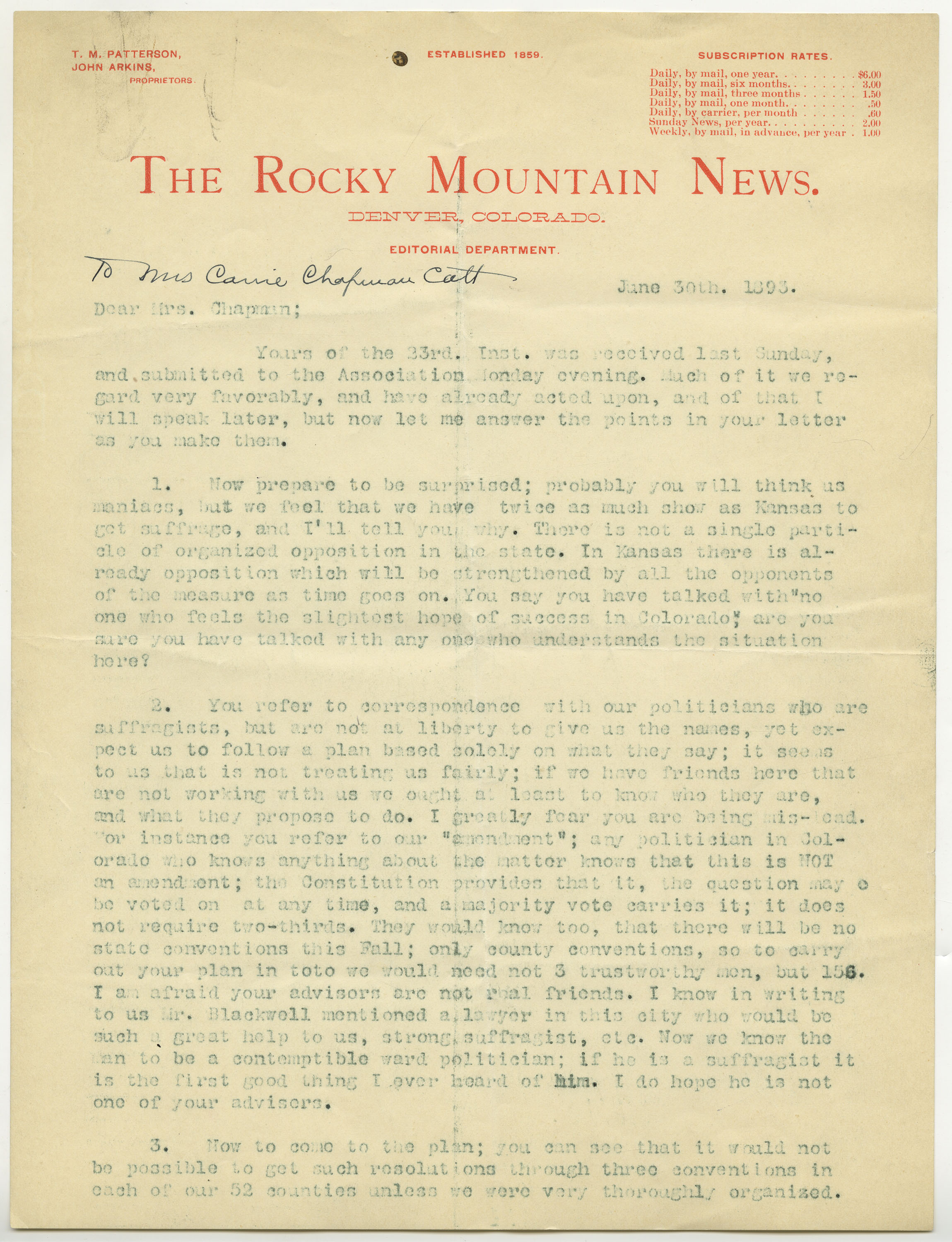

June 30, 1893 - Ellis Meredith to Carrie Chapman Catt

The political campaign was still being laid out in mid-1893, when Ellis Meredith wrote a lengthy letter to Carrie Chapman Catt of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), a frank, no-holds-barred assessment of the campaign and who the suffragists could rely upon.

The letter covers many other topics, but has been extracted here for clarity. Obviously this sort of strategy document would have been a gold mine to opponents if published in the anti-suffrage newspapers at the time. Among the zingers in this letter informing NAWSA of the situation in Colorado are takedowns of local politicians:

I know in writing to us Mr. Blackwell mentioned a lawyer in this city who would be such a great help to us, strong, suffragist, etc. Now we know the man to be a contemptible ward politician; if he is a suffragist it is the first good thing I ever heard of him. I do hope he is not one of your advisors.

We wish we knew what lawyer Ellis was referring to, but it’s lost to time. Meredith was careful not to reveal the name of the lawyer she was slandering (perhaps aware that private words in print have a habit of becoming public one day), but she was less cagey when it came to her dismissal of two speakers from Kansas whom Catt had suggested. Mary Elizabeth Lease and Annie L. Diggs had risen to political prominence in a campaign that led to the formation of the People’s Party in 1890. Lease was known to urge Kansas farmers to “raise less corn and more hell,” and Diggs was a harsh critic of capitalism involved at that time in a scheme to promote a new utopian society on Colorado’s Western Slope (which became today’s town of Nucla). Meredith doesn’t mince words about the pair:

Neither Mrs. Lease nor Mrs. Diggs would do here, I am told; they are ultra, and say very ill-advised things.

She also commented on the relationship between the suffrage association and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, noting that while they shared the goal of winning the women’s vote, it was not a fully aligned partnership. Perhaps looking forward to toasting the campaign’s success with an unprohibited beverage, Meredith noted:

We have already asked help from the W.C.T.U. and they have promised to make suffrage the dominant issue, but prefer to work by themselves; it is better that they should, than that they should try to ring in prohibition on us.

And she laid out what would become the dominant strategy based on the lessons learned from the campaign in 1877:

Now let me explain as well as I can what we mean by a “quiet campaign”: Do you remember Mrs. Nicholls? She was a wheel-horse in 76-77; so was Judge Bromwell and some other people that we have consulted; they say work among your friends, get votes for it; many who would vote against it will never discover it on their ballots unless you tell them.

“If Your Sex Were As Well Endowed With Intelligence as Yourself” (Be Mindful of What You Put in Print and How it Might Look in Hindsight)

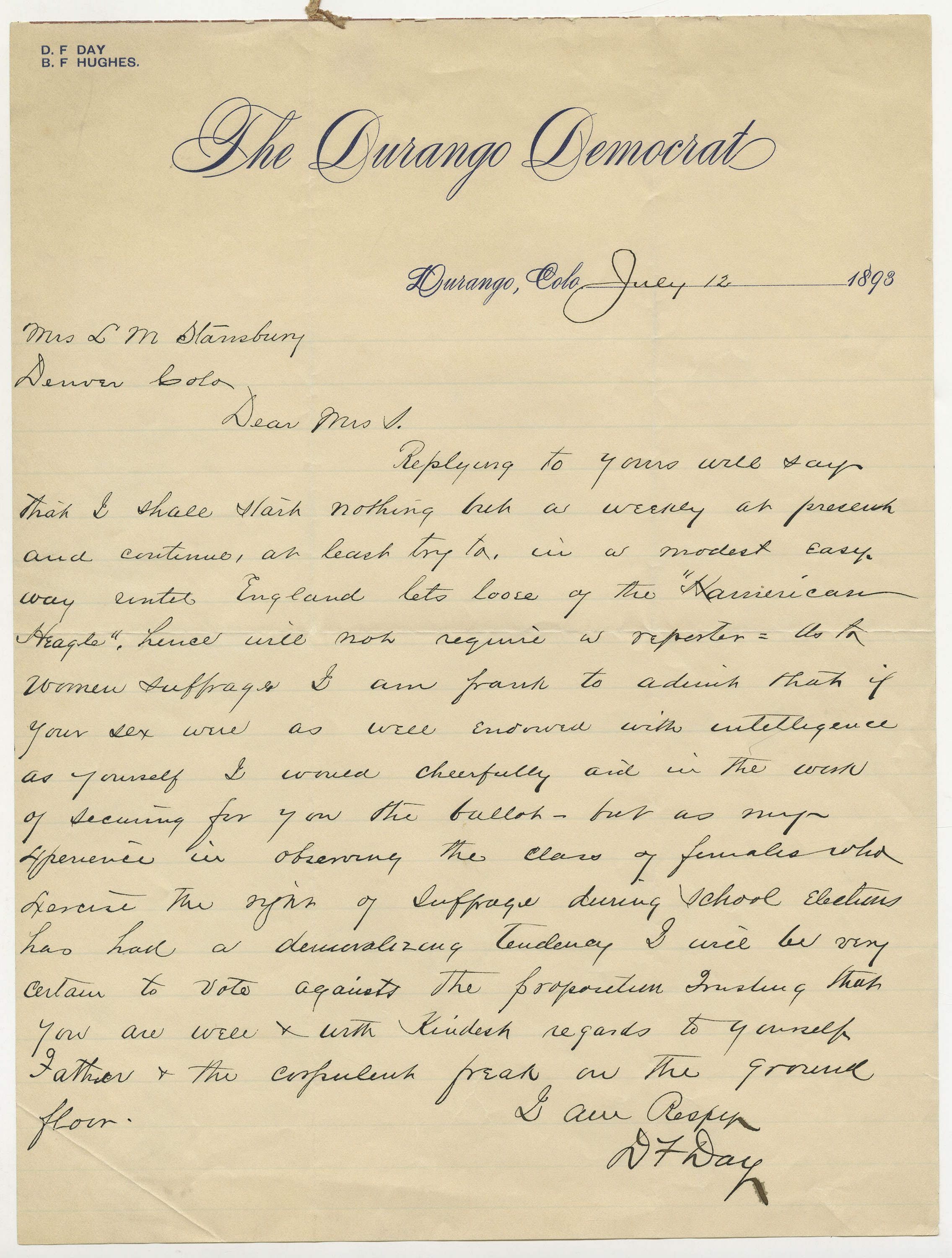

July 12, 1893 - D.F. Day to Ellis Meredith

Ellis and the other members of the suffrage association embarked on a letter-writing campaign to local newspapers throughout the state. Knowing how poorly the 1877 campaign had gone in southern Colorado, they especially wanted support from those newspapers. Unfortunately, D.F. Day, the editor of the Durango Democrat said he would not support the cause. He explained, “my experience in observing the class of females who exercise the right of suffrage during school elections has had a demoralizing tendency,” in the nineteenth-century equivalent of a resurfaced tweet that the author will now never outlive. Ellis knew Day, probably because of his connection to the Colorado newspaper publishers. He ends the letter in an informal way, as he clearly knew Ellis personally, yet leaves no clue as to the identity of the “corpulent freak” at the Rocky Mountain News he so fondly mentions.

"The Durango Democrat \ Durango, Colo July 12 1893 Mrs. LM Stansbury Denver [---] Dear Mrs. S. Replying to yours will say that I shall start nothing but a weekly at present and continue, at least try, in a modest easy way...As to women suffrage I am frank to admit that if your sex were as well endowed with intelligence as yourself I would cheerfully aid in the work of securing for you the ballot - but as my experience in observing the class of females who exercise the right of suffrage during school elections has had a demoralizing tendency I will be very certain to vote against the proposition. Trusting you are well and with kindest regards to yourself, Father and the corpulent freak on the ground floor. I am Respectfully DF Day

Who’s Left Out (Exclusion Isn’t a Good Look)

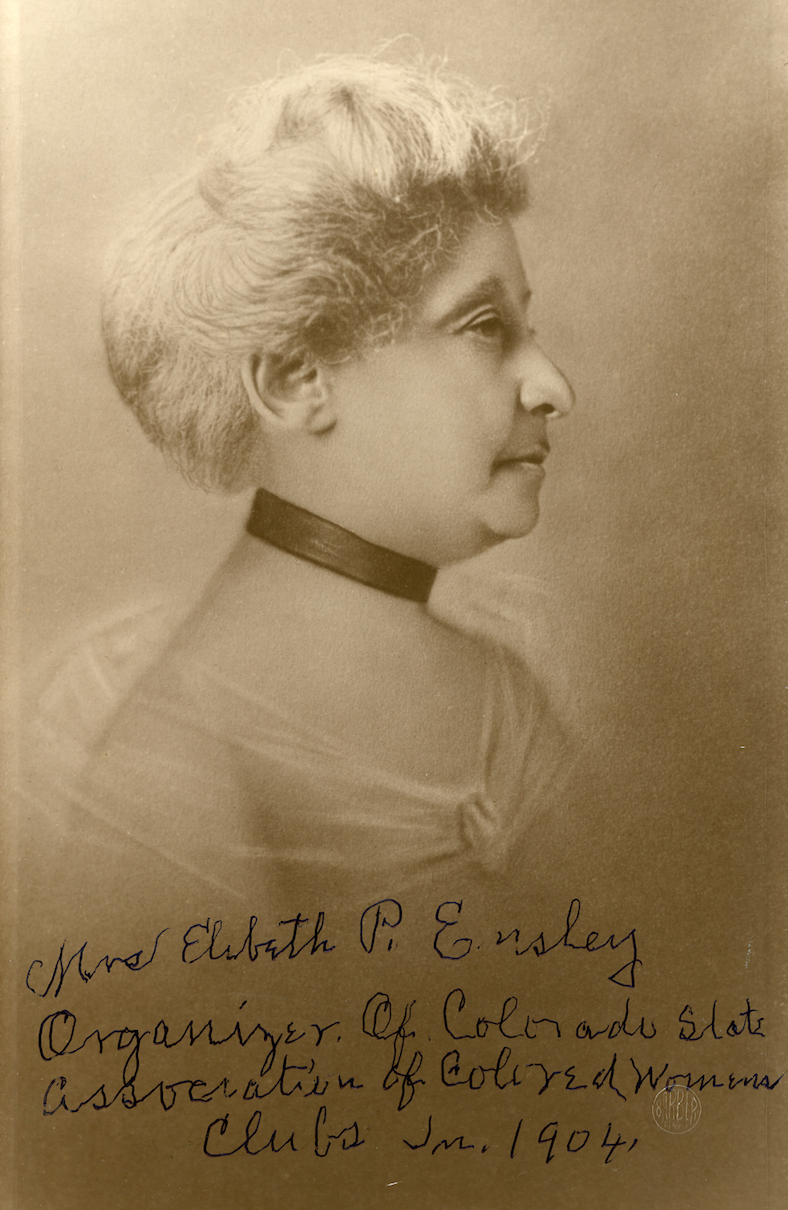

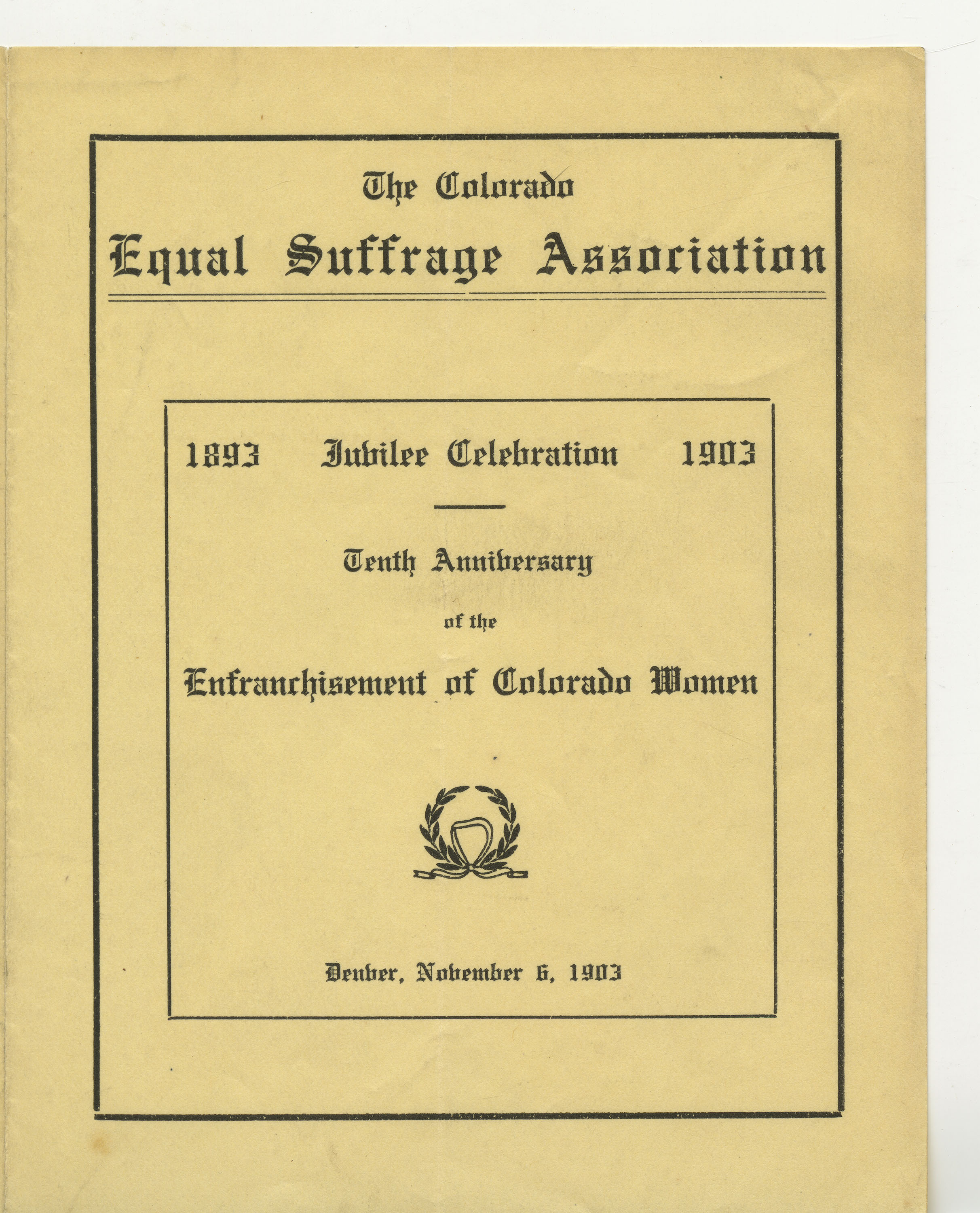

1903 Jubilee Celebration Program

Ten years later, however, in 1903 a dinner celebration was held to commemorate the victory. Several board members from 1893 were presenting. Mrs. Ensley, who by this point was the State Organizer of the Colorado Colored Women’s Clubs and who was serving on their national board, was left off the speaker’s list. It turns out white female politicians weren’t all that different than men. They knew which way the wind was blowing and were willing to use racism and bigotry to elevate their causes. Ensley’s exclusion may have been explicitly because of her race, but it may also have been because of who else was coming to power in Denver at the time.

Minnie Love, who was on the board of the Denver Suffrage League in 1893, had a much more limited role in the suffrage campaign but was given prominent placement at the 1903 event alongside Denver’s mayor and a couple of former governors. By this point, Love was one of the founders of the project that became Children’s Hospital, as well as the State Industrial School for Girls and the Florence Chittenden Home. She would go on to be the head of the Women’s Auxiliary of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s.

We don’t know if it was overt racism on behalf of the rest of the organizing committee, or merely an omission, but it’s not a good look to our present eyes.

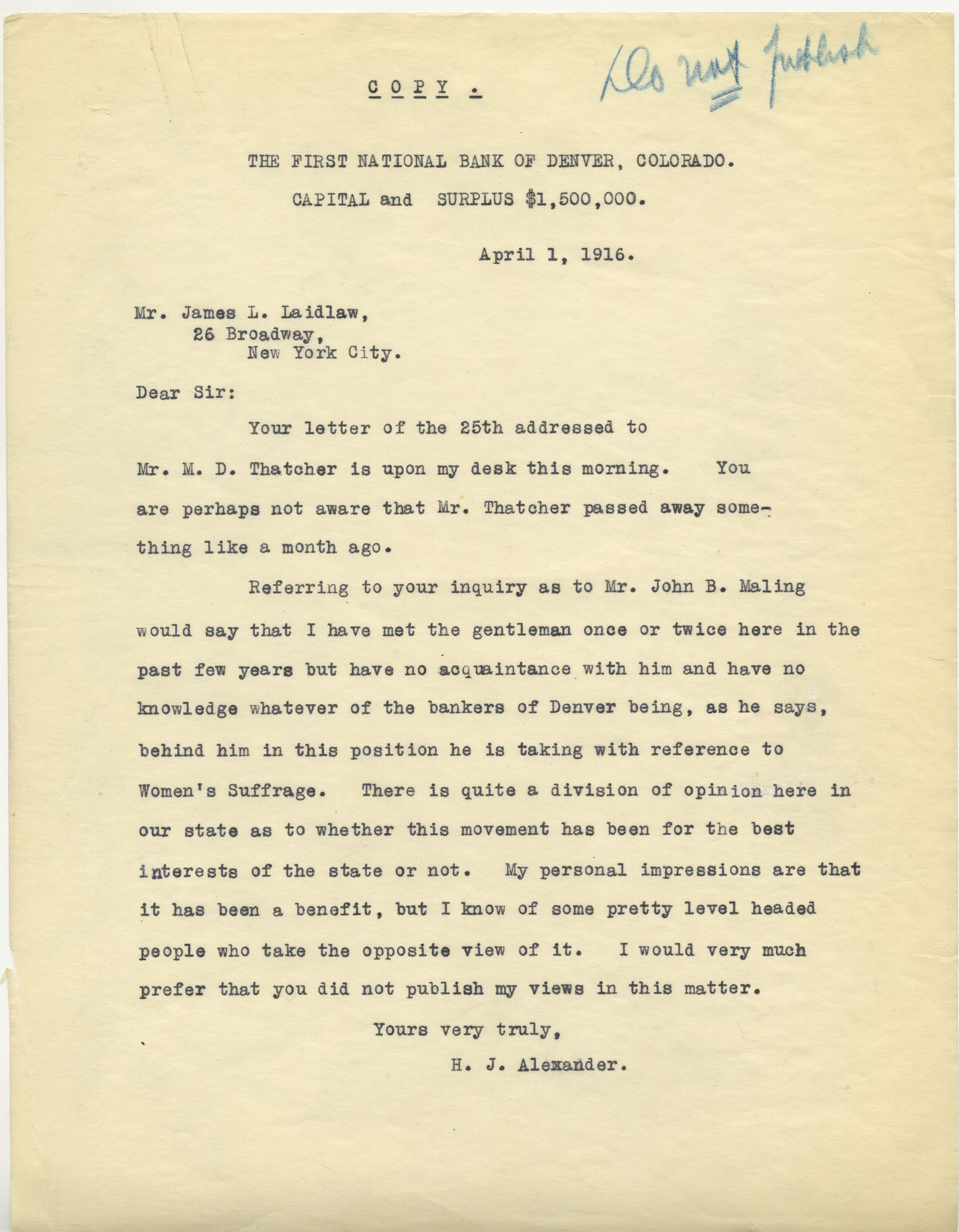

“I Would Very Much Prefer That You Did Not Publish My Views” (Don’t Count on Things in Writing Staying Confidential)

Letters on suffrage from Colorado bankers, 1916.

Because Colorado was an early adopter of suffrage, as the issue continued to grow throughout the country the state became the subject of scrutiny as to how women had impacted politics. A minor scandal was caused by one J.B. Mailing, who claimed to be associated with the business community of Denver. He blamed Colorado’s labor strife, including the Ludlow Massacre, on women voters. Suffragists on the national scale reacted quickly, soliciting letters of support from various “leading men of Denver.” Among the seventeen pages of supporting letters, some specifically say not to publish them. In the nineteenth-century equivalent of “please delete this text,” Hugh J. Alexander of the First National Bank of Denver said that he didn’t know of Mr. Mailing well, and that:

There is quite a division of opinion here in our state as to whether this movement has been for the interests of the state or not. My personal impressions are that it had been a benefit, but I know of some pretty level headed people who take the opposite view of it. I would very much prefer that you did not publish my views in this matter.

He wasn’t alone, but his carefully held political views in support of suffrage were still helpful to the national association, as they knew they had another friend in Colorado.

More from The Colorado Magazine

Cycling into Spring Susan B. Anthony claimed that bicycling “has done more to emancipate women than any one thing in the world.” One bicycle on display at the History Colorado Center offers insight into the pedal-powered campaign for the women’s vote in Colorado.

A Big, Complex, and Incomplete Story of the Vote In the fall of 2018, Jillian Allison started working on plans to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. As we mark this occasion on August 26, what she thought would feel like an ending to this work feels like just the beginning.