Story

Azalia Smith Hackley—Musical Prodigy and Pioneering Journalist

In honor of Women’s History Month, we’re highlighting Emma Azalia Smith Hackley, a former resident of Denver and co-editor of the newspaper the Statesman. The Statesman, which later became The Denver Star, will be the first of 18 titles History Colorado is digitizing to add to the Library of Congress Chronicling America database. If you’d like to learn more about History Colorado’s participation in the National Digital Newspaper Program, please follow this link.

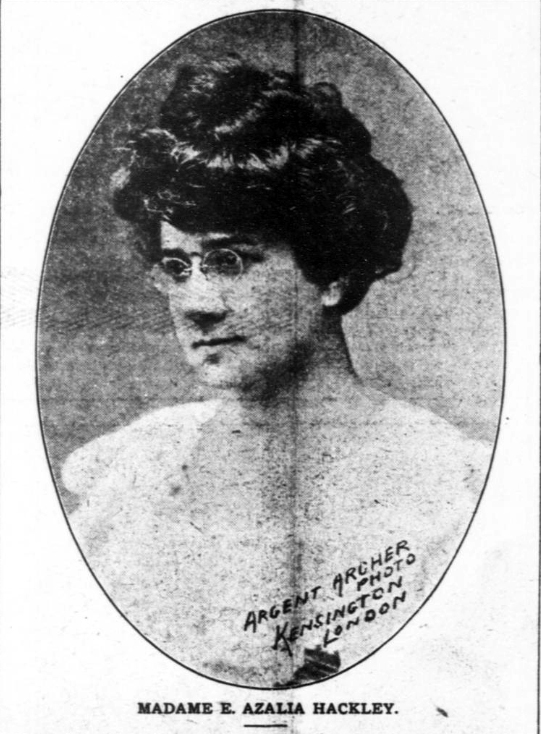

The event of the week was the recital of Mme. E. Azalia Hackley at Zion Church Monday night. Seven years have passed since she left the city yet for months talks of her coming has pervaded musical circles and spread throughout the masses and classes of the city. It is in a rare tribute to her personality and to the value of the work she did while here that so much personal interest was taken in the success of her recital. And hours before the time of opening crowds surrounded the doors of the church and standing room was all that was left by the time of the opening number.

—Statesman, June 6, 1908

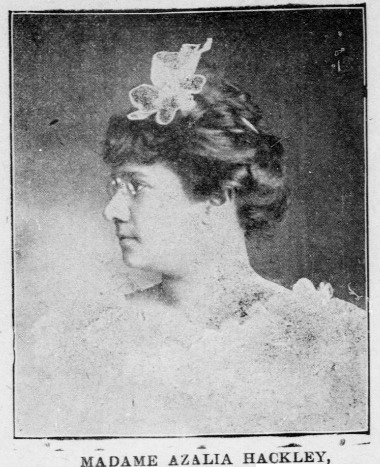

By all accounts, and there are several, Emma Azalia Smith Hackley was a remarkable woman. She was born in 1867 in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, where her mother, the daughter of a freed slave, founded a school for former slaves and their children. Forced to close the school by the white community there, the Smith family moved to Detroit, Michigan. Here, Azalia Smith, the first Black student to attend her public school, developed her prodigious musical gift—taking violin, piano, and singing lessons—and contributed to her family’s income by singing and playing piano at high school dances. She graduated high school with honors and worked her way through normal school by giving piano lessons, after which she taught in a public school, all while continuing piano and violin lessons as well as French and singing for the Detroit Musical Society.

In 1894, Azalia Smith eloped with Denver attorney Edwin Henry Hackley and returned to Colorado with him. Edwin Hackley himself was an impressive figure, particularly in Colorado politics and publishing. Edwin was a University of Michigan-educated lawyer, who besides being admitted to the Michigan bar, was the first African American lawyer to be admitted to the Colorado bar. While in Denver, Edwin joined Joseph D.D. Rivers—a former student of Booker T. Washington at the Hampton Institute—to form the Colorado Statesman newspaper (alternately known as the Denver Statesman), the first iteration of what later became the Statesman and eventually The Denver Star. Begun in 1889, with Hackley serving as editor in 1892, the Statesmanbecame the preeminent paper by which the African American communities of Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and the West could “voice their opinions, assert their rights, and demand their due recognition.” 1 Hackley also originated the American Citizens’ Constitutional Union, “designed to unite the efforts of the colored people in all parts of the country for the advancement of their rights and opportunities.” 2

The newly married Azalia Smith Hackley enrolled in the Denver University School of Music and when she graduated with a Bachelor’s of Arts from the music school in 1900, she was the first Black student to do so. The Statesman reported, “Mrs. Hackley…is the pride of the faculty and college and one of the most thoroughly educated musicians of her race.” Racial pride and activism were important to the Hackleys. Even as she pursued her music degree, and served as the choir director at her church and the assistant director of a large Denver choir, Azalia also devoted time to Black organizations. She founded a branch of the Colored Women’s League in Denver and as editor of the women’s section of the Statesman, called the Exponent, she advanced the agenda of the League. In one column she wrote:

In mapping out this program we have borne in mind the great need for thought and talk on the practical as well as cultural side of woman’s life. Our first work will be toward the education and improvement of our Colored women and the promotion of their interests. 3

Those interests, as discussed in the pages of the Statesman Exponent, included “Hygiene, Current Events, Civil Government, Importance and Compiling Facts about the Negro, English Literature and Literature on the Negro, Household Economies, Influence of Music in the Negro Home and on Youth.” 4 (It’s interesting to note that Azalia Smith Hackley, among her many accomplishments, also wrote the first etiquette book for African American women, The Colored Girl Beautiful, in 1916.) 5

All the while, Azalia performed publicly to great acclaim. The Denver Post reported:

Mrs. Hackley is considered one of the best vocalists in the city. Under her direction Denver is doing more musical work among the Colored people than any other city in the West…her concerts draw audiences that fill the churches to the door. 6

Azalia was a proponent of music as a means of advancement and promotion of racial pride and was quoted to have said: “I want my concerts to be more than a mere evening of musical enjoyment; I want to plan them so that the youth may be inspired, stimulated, and trained at the same time.” 7

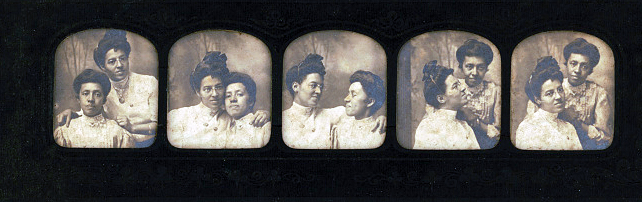

Emma Azalia Smith (wearing spectacles) with activist and educator Elizabeth Carter Brooks, 1885, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

By 1899-1900, Edwin Hackley sold the Statesmanto its next owner, G. F. Franklin, who, along with his wife and son, published the Statesman-cum-Denver Star well into the 1910s. After the sale of the paper, Edwin turned his attentions to practicing law and with the assistance of Azalia, organized the Imperial Order of Libyans, a fraternal, patriotic, racial, militant, beneficent organization which worked toward the “dissipation of social bigotry and the combating of racial prejudice, the equalization of citizenship and the cultivation of patriotism.” 8

Together, Azalia and Edwin were movers and shakers in the African American community of Denver—socially, politically, and culturally. However, in 1901 Azalia left Edwin and moved to Philadelphia to continue her career as a notable choral director, particularly of the 100-member People’s Chorus (later known as the Hackley Choral) and later moved to Paris to study voice under a well-known opera singer and vocal coach. 9

Azalia Smith Hackley’s celebrated return to Denver in 1908 encapsulates the significant role she played in nurturing the arts and culture among both the Black and white communities of Denver as well has her tireless advocacy on behalf African Americans in the West. Likewise, Denver had an important place in Azalia’s professional and personal development:

With Denver has come breadth and real living. Before it there was no assurance of serious, purposeful work. To Denver, I owe much—to its schools, its churches, its people…10

Emma Azalia Smith Hackley—musical prodigy, teacher, newspaper editor, community organizer, author, and activist—spent her life promoting Black music and training Black musicians. She founded the Vocal Normal Institute in Chicago and organized the Folk Songs Festivals movement in African American schools and churches throughout the South. She traveled far and wide, even visiting Tokyo, where she introduced Black folk music to an international audience at the World Sunday School Convention. 11 Azalia died in 1922, in Detroit, where the E. Azalia Hackley Collection of African Americans in the Performing Arts was established in her honor in the Detroit Public Library.

Sources

- Davenport, M. Marguerite. Azalia: The Life of Madame E. Azalia Hackley. Boston: Chapman & Grimes, 1947, 77. (March 16, 2017.) https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b3247480.

- Castle Rock Journal, December 16, 1891. (March 16, 2017.) https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/cgi-bin/colorado?a=d&d=CRJ18911216.2.16&srpos=1&e=

- Davenport, 93.

- Ibid., 93-94.

- Hackley, E. Azalia. The Colored Girl Beautiful. Kansas City, Mo.: Burton Pub. Co., 1916.

- Davenport, 87.

- Davenport, 88.

- Davenport, 94

- “Hackley, E. Azalia Smith (1867–1922).” Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Encyclopedia.com. (March 16, 2017.) http://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/hackley-e-azalia-smith-1867-1922.

- Davenport, 85.

- “Hackley, Emma Azalia (1867-1922).” BlackPast.org. (March 17, 2017.) http://www.blackpast.org/aah/hackley-emma-azalia-1867-1922

The Colorado Digital Newspaper Project has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the human endeavor.