Story

The Denver Artists Guild: How Much Do You Know About It?

Barbara E. Sternberg was a member of the Denver Woman’s Press Club who in 2011 wrote the biography Anne Evans—A Pioneer in Colorado’s Cultural History. This article is reprinted with permission from the blog Sternberg developed after this book was published. Anne Evans was a resident of the present-day Center for Colorado Women’s History at the Byers-Evans House Museum, one of the statewide Community Museums of History Colorado.

History Colorado’s lavishly illustrated book by Stan Cuba [The Denver Artists Guild: Its Founding Members; An Illustrated History, 2015] focuses attention on the 1928 founding of the Denver Artists Guild. The response of far too many people, on becoming aware of it, is, “What is the Denver Artists Guild? I never heard of it.” Indeed, an article in Westword (June 26, 2015) proclaimed that these exhibits and the book bring “an obscure chapter of local art history to life.”

If you do not feel as well informed as you would like to be about the Denver Artists Guild, now is the perfect time to remedy this deficiency and have a good time in the process. Spend a few evenings reading the new book on the guild and marveling at its profuse and handsome illustrations—reproductions of the work of many of the fifty-two founders of the Denver Artists Guild.

Foreword by Hugh Grant

[Founding director and curator of the Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art] Hugh Grant rightly points out, in his brief and informative foreword, that a 2009 exhibit at the Denver Public Library [DPL] was the effective forerunner to exhibits about the [guild] put on view at the Byers-Evans House Museum and the Kirkland Museum. Stimulated by the research of Deborah Wadsworth, a tireless volunteer in the Western History Department of the DPL, the exhibit Fifty-Two Originals featured work by many of the fifty-two founders of the Denver Artists Guild. Hugh Grant gave a lecture about the guild at the Denver University School of Art and Art History: “I think practically all of my listeners . . . were struck by the scope and quality of the 106 works of art representing forty-two artists. Because all exhibitions must end, a number of us determined to do something lasting to tangibly preserve the history of the guild. This book is the result.”

Introduction by Cynthia Durham Jennings

Information about the guild, and about the lives and work of the fifty-two founding guild members, would be infinitely less complete without the many years of patient research done by Cynthia Durham Jennings. Her research centered at first on her father, Clarence Durham, a major founding member and five-term president of the group. After his death in 1994, Cynthia began looking into his background and his long-standing membership in the guild, with a view to “writing a book about him to help preserve his legacy.”

As Durham Jennings’ research efforts became more widely known, several individuals seeking information about other founding members approached her. When she realized how little was known about the guild and its members, she resolved to widen the scope of her project. She recruited two colleagues to help her in what proved to be a time-consuming and difficult task—gathering information about as many of the fifty-two founding members as was humanly possible. Many of the original members had died or moved away from Denver; some of the women had remarried and acquired new names. On the positive side, family members, when traced, often provided photographs, biographies, and locations of artwork that was photographed. All possible sources, from old scrapbooks kept by guild members to the Internet, were canvassed.

Using the material so gathered, Stan Cuba, associate curator of the Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art, “prepared the members’ biographical entries, helped with the final selection of color reproductions and captioned them, and wrote an extensive historical overview introducing readers to the general subject of the guild and documenting the heretofore little-known story of its fifty-two founding members.”

Stan Cuba’s Story of the Denver Artists Guild

The Denver Artists Guild—renamed the Colorado Artists Guild in 1990 to better describe its area of activity—is the second oldest artists’ organization in Colorado. The oldest is the Denver Art Museum, which had its origins in the Denver Artists’ Club, founded in 1893. The guild’s original membership included many of the best-known Colorado artists of the day, including Dean Babcock, Albert Bancroft, Donald and Rosa Bear, Frederic Douglas, Clarence Durham, Anne Evans, Gladys Caldwell Fisher, Laura Gilpin, Elsie Haynes, Marion Hendrie, Vance Kirkland, Waldo Love, Albert Olson, Paschal Quackenbush, Anne Van Briggle Ritter, Arnold and Louise Ronnebeck, Paul St. Gaudens, Elisabeth Spalding, David Spivak, John E. Thompson, Allen Tupper True, and Frank Vavra.

The mission of the new 1928 organization, as described in the Rocky Mountain News (June 10, 1928) on the occasion of the opening of the guild’s first exhibit of members’ work, was: “To promote a spirit of professional cooperation and maintain a high standard of craftsmanship among the artists of Denver and vicinity, [and] to bring to the attention of the public representative works of these artists in painting, drawing, sculpture, ceramics and the graphic arts (etching, lithography, etc.).”

Development of the Denver Art Museum

In his chapter on the history of the guild, Cuba tells the story of the evolution of both the Denver Artists Guild the Denver Art Museum [DAM]. He describes how local Colorado artists were active in the DAM’s programs and played an essential role in its development. But he also makes clear that, as perhaps an inevitable result of the widening sphere of the DAM’s activities, there came a time when it could no longer fulfill the needed function of nurturing and sustaining local artists.

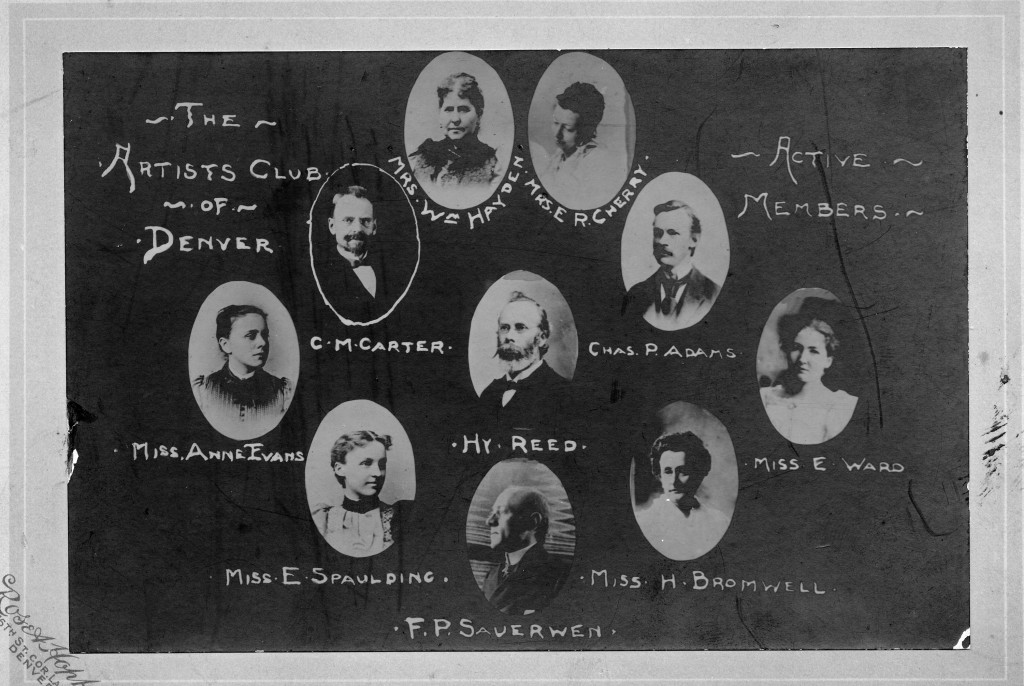

Originally the 1893 Denver Artists Club was an organization of Colorado artists dedicated both to increasing public awareness of the offerings of local artists, and to educating the public about developments in the wider world of art—nationally and internationally. The group sponsored annual juried exhibits, not only of members’ work, but also featuring well-known artists from the East and Midwest. From the beginning, the club sought associate members to augment its financial resources and to help carry out its mission in the wider Denver community. In 1917, feeling that its original name was too narrow as a description of its activities, it was renamed the Denver Art Association.

The organization began to collect the beginnings of a permanent art collection, which, until 1922, had to be displayed in galleries of the Museum of Natural History in City Park. In that year, a huge boost in the fortunes of the [Denver] Art Association came with the donation to it of Chappell House, a large mansion at 1300 Logan. Though falling short of the [Denver] Art Association’s ultimate objective—a spacious museum on the new Civic Center—Chappell House was an invaluable asset, the DAM’s first real home. In 1923, the Denver Art Association became the Denver Art Museum. It began a long journey, not only to secure its coveted place on the Civic Center, but also to become the official “art arm” of the City and County of Denver.

A Need That Could no Longer Be Ignored: The Story of the Denver Artists Guild

And so, by 1928, the artists of the growing Denver area “felt the need for a successor organization to the Denver Art Association and the Artists Club. They desired the backing of a formally constituted, democratically oriented group open to all Denver-area artists capable of sponsoring their own traveling and annual exhibitions. They also sought to encourage among the city’s artists the same mutual support and enthusiasm they had experienced as members of these two predecessor art groups through monthly meetings and lectures, sketching trips, dinners, and other social events.”

Albert Bancroft, a Colorado native and a well-known Denver artist, was the leader in the 1928 organization of the Denver Artists Guild, ably assisted by two other prominent Denver artists, Dean Babcock and David Spivak. According to Stan Cuba, “Most of Denver’s artists responded to Bancroft’s invitation to join the guild, initially paying annual dues of $15 per person—not an inconsiderable sum at that time. However, when the Great Depression began to negatively impact artists’ incomes, dues dropped to only $3 per year.”

Cuba goes on to describe in detail the structure of the new organization [and] its lively program of activities for members: weekly guild meetings, monthly dinner meetings with substantial and informative programs offered by members, sketching trips, sessions of constructive criticism of current members’ works. The guild, in addition to its artist members, “solicited twenty-two patron members. Their yearly dues of $20 provided the fledgling group with additional capital for its organizational activities, particularly promoting the artist members by funding the guild’s annual exhibitions. . . .”

In the next section of his thirty-seven-(large)-page essay on “The Denver Artists Guild: Its Founding, Activities, and Legacy,” Cuba describes the work of the guild and its members through the First World War and the explosion of unconventional modes of artistic expression, the Great Depression, and World War II. He describes the locations where the work of many members during this time, in murals, sculpture, and paintings, can still be seen—from the State Capitol to the Civic Center, and to restorations of commercial buildings like the newly remodeled former Colorado National Bank Building complete with its original murals. Also he talks of the many art projects executed under the aegis of the federal government during the Depression era, in post offices and other public buildings.

1948: A Split in the Artists Guild

Cuba describes the Colorado artists’ version of a split that had been developing locally and nationally, since the beginning of the twentieth century, between traditional painters and those exploring ever more adventurous modes of artistic expression. In Denver, the actual split started with Vance Kirkland, then an important figure on the Denver art scene and the director of the Denver University [DU] School of Art. [Kirkland] infuriated Rocky Mountain News reporter Lee Casey with a public comment to the effect that “people who don’t know anything about art should keep quiet.”

Casey responded, in a Rocky Mountain News column, “Painting, as I view it, ought to bear at least some resemblance to what it is supposed to represent, and I can’t see that surrealistic paintings—or, for that matter, the paintings of any other special school since Picasso and Cézanne botched things up—do that. . . . We are, I am confident, advancing beyond the stage when the most-applauded painting might just as well be hung wrong end up. True art is timeless, and within a few years an original Picasso or Cézanne will be valued mainly for the frame.”

At this point, artist William Sanderson entered the fray. Sanderson was a talented artist and an eloquent teacher at the DU School of Art. He was an active member of the Artists Guild, though not a founding one. His response to Lee Casey was titled “Pioneers in Art.” He wrote, “If the artist [in our society] has the temerity to deviate from the phony formula of ‘tourist painting,’ he is labeled a fake, a zany, and generally a moral leper. . . . This part of the country is proud of its pioneer tradition. . . . the term pioneer is not confined to men who rode in covered wagons. Many artists are still trekking across the arid wastes of our intellectual deserts. They have a vision, and they hope it is not a mirage. In the meantime, instead of being scalped, the modern artists could use a helping hand once in a while.”

As the guild’s vice president and program chairman, Sanderson was experiencing the group’s “underlying conservatism and some members’ disdain for modern art.” Along with Sanderson, four other members seceded from the guild to [form] a new group, Fifteen Colorado Artists, which was composed mainly of faculty members from Denver University’s School of Art.

The guild leadership was at first afraid that the split would permanently fracture the comradeship of Colorado artists. But, in Cuba’s words, “All parties managed to weather the storm. In December 1948 both groups displayed simultaneously in adjoining galleries at Chappell House. . . . The Denver Monitor reported that both shows generated unprecedented public interest, confronting their viewers with the controversial question of modern versus traditional art.” Cuba suggests that in one way the split benefited the guild: It “gained a new sense of unity it had previously lacked on account of the growing controversy within its ranks.”

Over the years, the animosity between [the Denver Artists] Guild and the Fifteen Colorado Artists softened. The guild began to feature guest artists in its annual shows whose work was far less conservative than that of most of the guild members. And in 1963, William Sanderson was invited to be one of the jurors for the guild’s annual exhibition.

Summary: The Contributions of the Founding Members of the Denver Artists Guild

It was something of a shock to read the first words of Cuba’s final paragraph in this section of the book: “Although all of the organization’s founding members are deceased . . .” A shock because I personally knew a number of those members, so this statement is quite a reminder that I have indeed “grown old”!

Cuba concludes by paying a final tribute to these artists: “. . . the art they created and their multifaceted cultural pursuits remain an integral part of the cultural heritage of Colorado and the Rocky Mountain West.”