Story

“Openly and with Gusto”: How Women Moonshiners Led to Denver’s First Female Cop

Emerging Historians Award

This essay is the Best Undergraduate Essay winner in the 2019 Emerging Historians Award. Additional awards went to Jacob Swisher from Colorado State University, Best Overall Essay winner for "Were They Mexicans or Coloradans? Constructing Race and Identity at the Colorado–New Mexico Border" and Don Unger from the University of Colorado in Colorado Springs, Best Graduate Essay winner for

"Historical Perspectives of the 'World’s Greatest Gold Camp.'"

The Emerging Historians Award is a program of History Colorado’s State Historian’s Council. Find all three essays and details of the 2020 award round—with a submission deadline of June 1.

In the cool evening of March 14, 1918, Sophia Videl and a Ms. Behrman rolled into Colorado in their automobile over the New Mexico border, on their way to Creede. The dusty roads were lonely, and the pair hoped that their late-night cruise wouldn’t rouse suspicion. However, the solitary car piqued the interest of Deputy Sheriff Vic Stephenson, who rushed after them and pulled them over. When he leaned down to ask for identification, he was met with two women dressed in men’s suits, clearly nervous and hiding something. Upon further inspection of the vehicle, Sheriff Stephenson found five gallons, one quart, and one pint of bootleg whiskey.

Just two years prior, Colorado had passed a statewide prohibition on any and all alcohol, and by January 1920, the entire country was dry under the Volstead Act. Both women were convicted, given a $100 fine, and sentenced to sixty days in jail. Neither gave names connected to the illegal hooch in their car, and suspicion fell on them alone for its existence. After their arrest, reports from around Creede led the judge to suspect that the pair had been independently operating their own business for some time. The couple apparently wore suits often, lived together, and operated the production, movement, and sale of their “white mule” moonshine in the southwestern towns of Colorado.

Such behavior seemed unprecedented in this small community, and the editor of the Del Norte newspaper, The San Juan Prospector, published that he’d been asked not to write about the fact that these criminals were women. But he responded that the truth of their crimes proved their guilt regardless of ideals around femininity: “Sex should make little difference, in fact, women who stoop to disgrace their sex by peddling whiskey are deserving of no sympathy.”1 Such an event shocked the local community, and the story made headlines in newspapers around Colorado. This story of two cross-dressing women creating and maintaining a booze-smuggling operation would set the pace for a decade of unprecedented shifts in social relations in Colorado, particularly around the ways women were allowed to partake of alcohol. From the midst of a strictly gender-segregated culture, women in Colorado took full advantage of the economic and social nuances that came with the illegality of alcohol to gain a better place for themselves.

Women’s Christian Temperance Union members with the Great Petition for Prohibition, 1914.

It is important to note that one of the most strictly gendered activities in the western United States in the decades prior to Prohibition was the consumption of alcohol, specifically alcohol purchased in saloons. Saloons were associated with masculinity, and were often the haunts of single, poor laborers in the early years of Colorado’s history. Over the years, this tradition led to saloons becoming associated with activities such as gambling, prostitution, and, of course, drinking. When Coloradan women gained the right to vote in 1893 many people believed that saloons enticed disenfranchised women into lives of poverty and abuse; this belief gained traction in the decades prior to Prohibition.2 These new female voters felt that by preventing women from entering spaces associated with alcohol, they were curing social ills and saving lives. Male voters at the time also agreed that drinking should be a strictly male-only activity.

These cultural objections to the mixing of women and alcohol led to a law that passed in Colorado in 1901 prohibiting women from entering saloons. Under this law, not only were women not allowed to buy alcohol, they were not allowed to work in any place that sold alcohol, or that was even next door to establishments that sold alcohol of any kind. The law, which revoked the rights of women to even buy a drink, was predicated on a society that saw women as strictly domestic-bound beings; in other words, the law was not seen by those who voted for it as oppressive, it was seen as a necessary enforcement of good morality. Beyond this law, women were not allowed to consume alcohol in public settings, and partook in drinking only within the confines of their own social spheres among other women (usually in their own homes). The only women culturally “allowed” to enter saloons were entertainers and prostitutes, and the social understanding of women and saloons came to meet that idea. Male drinkers in Denver relied on this assumption to call female reformers “whores” when they entered saloons to record the conditions of drinkers.3 Places where men consumed alcohol were often rough-and-tumble hotspots packed with billiards, cards, and brawls. Alcohol in Colorado was a man’s fare, and it was for men alone to publicly consume.

This law clearly illustrates Victorian ideals around the societal function of women. Women, according to Victorianism, should serve society by purifying it from the inside out, through good motherhood that bred morally upright adults. This ideology placed women only in the home, and put the entire burdens of homemaking and child rearing on them. Most importantly, the morally motivated reasoning behind a woman’s purpose/role in Victorian society placed them firmly in the domestic realm. The public and private spheres were inherently gendered for only men or only women, respectively, and it became culturally taboo for these spheres to cross. In order to adhere to this expectation, women did not have public lives outside the home in the way that their husbands did, and a “good woman” certainly would never have consumed alcohol in public. The 1901 law barring women from alcohol was not unprecedented; rather, it was a product of an already very restrictive and gender-divided culture.

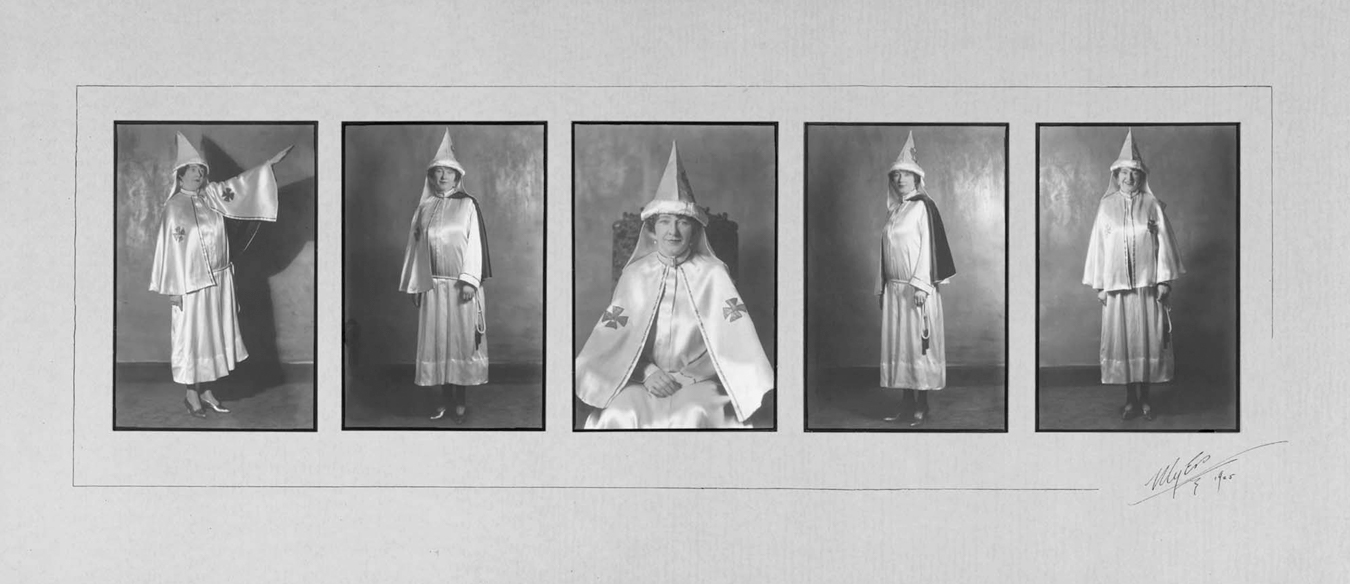

Dr. Minnie C.T. Love, called “excellent commander” of the women’s Ku Klux Klan, was also a prominent member of the WCTU.

It was this same spirit of moral enforcement that caused statewide prohibition of alcohol to pass in 1916; Colorado went dry four years before federal Prohibition was enacted. The Volstead Act, which federally prohibited alcohol, passed on January 16, 1920, and defined “intoxicating liquor” as any beverage containing more than 0.5 percent alcohol. This decree included any and all alcohol, even alcohol for religious or medicinal purposes. One of the main reasons Prohibition was able to pass was because of the concentrated efforts of political activist groups who worked to make alcohol entirely illegal; among the foremost of these groups was the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).

The WCTU had chapters all across the United States and, as the name implies, was run exclusively by politically active women. The WCTU of Colorado was organized in Longmont April 1–2, 1880. The group’s members were open about their religious and moral reasons for wanting Prohibition, often blaming the “demon drink” for ruining lives and wrecking homes. They, along with other Prohibitionists, viewed alcohol in much the same way as something like methamphetamine is seen today; they felt that it was extraordinarily addictive, and that even a single sip could lead to a life in ruins.4 Unlike the voting populace who wished for alcohol to remain legal, the WCTU was extremely coordinated and was an organization that lived up to its battle cry to “organize [and] agitate".” It is also quite noteworthy that many members of the WCTU were also prominent members of the Ku Klux Klan in places such as Denver.5 While not every member of the WCTU was in the KKK, many women held these overlapping memberships because the sentiments behind banning alcohol were also born in great part from thoughts that were openly anti-immigrant and opposed to non-Protestant religions—beliefs that aligned with those of the KKK. It is clear that women who held a membership in the WCTU felt an imperative to purify society; those who held a membership in both organizations clearly articulated that that imperative was Protestant, moral, and intended to force a very specific kind of conformity onto society at large.6

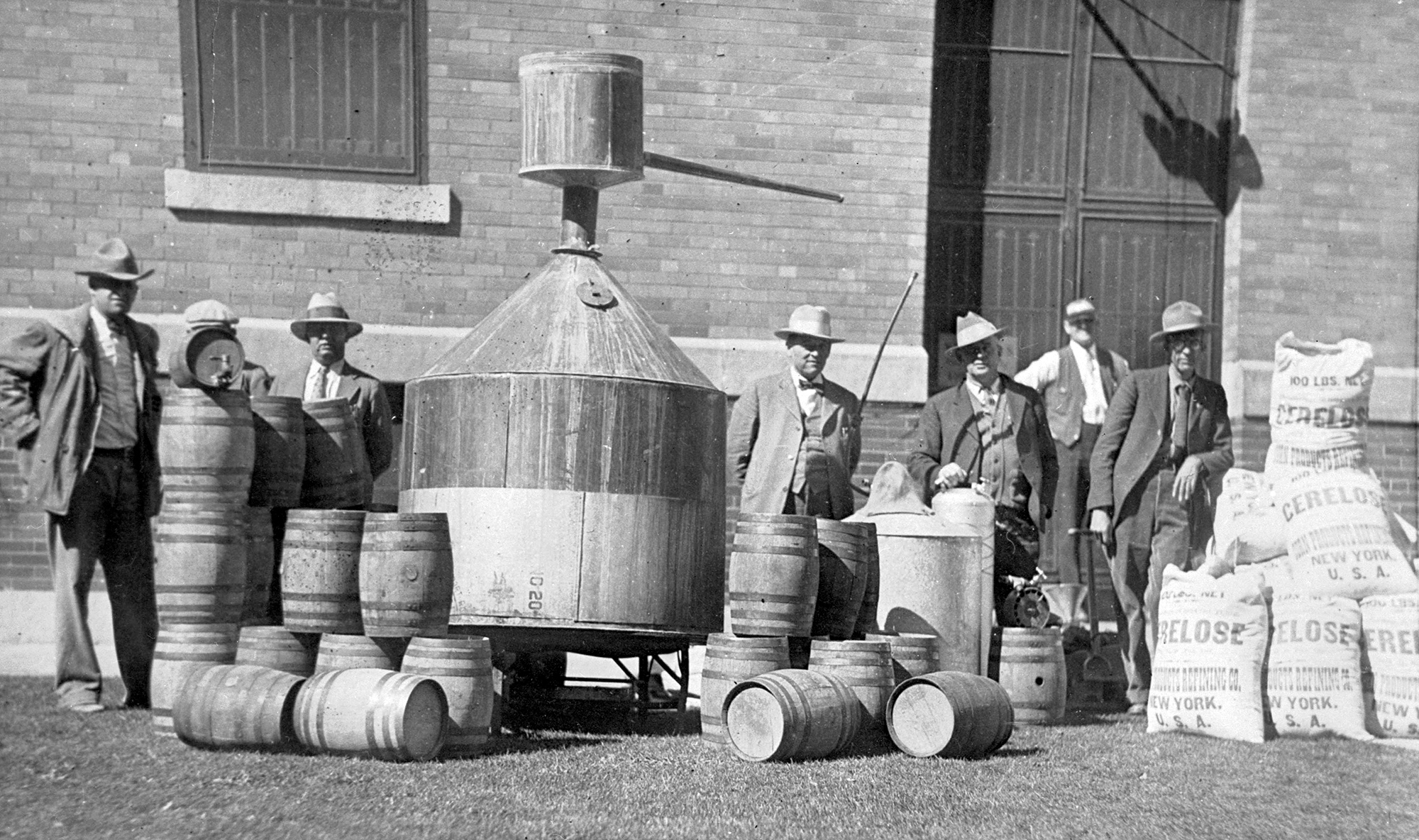

Whether they were KKK members or not, the concerted efforts of the women in the WCTU were in great part responsible for Prohibition becoming law. The Speaker of the House for Colorado, Philip B. Stewart, said when statewide Prohibition was passed that “by honorable lobbying, the WCTU placed the Prohibition enforcement law on the statute books.” Thousands of breweries and saloons went out of business in Colorado, and many scrambled to convert to other ways of generating revenue, such as soft-drink parlors. By 1917, Prohibition had closed 1,615 saloons and seventeen breweries in the Denver-metro area alone.7 Saloons that were converted into soft-drink parlors often still served alcohol, and it is impossible to know how many speakeasies were in operation, but the evidence suggests a multitude. Newspapers in Colorado during Prohibition reported police raiding booze parties at least once a week, and privately run moonshine stills were discovered and shut down almost daily. All across Colorado, a simple law seemed unable to curb a well-established cultural staple like alcohol in the lives of its citizens.

A woman sits for her mugshot after being taken in for violating Prohibition laws in Denver, 1920s.

As soon as alcohol was illegal, the black market for it came into existence practically overnight. With the demand for alcohol now extremely high across all strata of society, women were able to participate both socially and economically in making and consuming it at unprecedented rates. Culturally speaking, Prohibition allowed for women to enter into social spaces that had simply not existed before. Because alcohol was equally illegal for every person, speakeasies developed as places where both women and men could get a drink; in other words, because alcohol was illegal, women were able to create and participate in spaces where they could publicly participate in a traditional Colorado leisure culture. The inherent irony of Prohibition in Colorado is that, in essence, the Prohibition movement was started by and legally passed by the concerted efforts of the female voting population, yet it was their own daughters who ignored it in sweeping fashion.

In the 1920s women held every sort of illegal job pertaining to booze, from running the kitchen stills, to peddling the booze, to tallying sales records, to smuggling it, to driving it across borders. After the passage of Prohibition, young mothers, daughters, and socialites stood before puzzled judges to defend themselves against bootlegging charges. For example, in April of 1924 a Denverite named Lucy Dentoni, as well as her small child, were taken to the matron’s quarters of the city jail, where she awaited charges of violation of Prohibition laws. State agents raided Dentoni’s home after she had sold one of them a bit of wine the night before, and in her home, several gallons were confiscated.8 Nobody else was ever arrested for the illicit wine, pointing to the possibility that Ms. Dentoni was a single mother who sought financial security in the demand for wine within her community. Her story is relatively typical of those that the newspapers published on female bootleggers. Most took part in small-scale and personally run operations that locally sold their wares. As long as a woman had access to a kitchen, she likely had the ability to make booze, and many women took full advantage of that fact to the point that women were most likely contributing significantly to the black market.

Even women who only had a studio apartment to their name partook in making booze. On July 10, 1924, a young woman called F. Stone was arrested for operating a “pocket still” out of her small apartment at 4008 Tejon Street; it produced at a pint an hour. Instances like this prove the industriousness of women in this remarkably transitionary era. We also know that many women found great financial success by peddling booze. Anna Butler was the owner of a boarding house in Denver during the 1920s, and was caught selling alcohol to her patrons. Her record book showed that for the previous few weeks, her salary had averaged $150 per day.9 In 1924, the average (Caucasian male) yearly income in the United States was around $1,300, so a woman making $150 through illegal alcohol production points to a heavily demanded black market economy, and women were very able and eager to fill that demand.10

Left, March 6, 1921 Denver Post story about the formal jiu-jitsu and revolver training Officer Edith Barker received. Center: Barker escorts a kidnapping suspect off a train, 1931. Right: A portrait of Officer Barker in The Denver Post of June 10, 1928.

Women were also often successful bootleggers because they enjoyed a level of legal anonymity surrounding alcohol, as Victorian ideals around social purity and femininity clouded the reality that women were capable of such things. Despite those perceptions, more often than not when law enforcement was tipped off to moonshine stills, the primary laborers behind the operations were women. Women could gain significant economic freedom in Colorado during Prohibition by running small-scale stills in the privacy of their own kitchens—a realm still deemed for women only. Contrary to the intent of Prohibitionists, making alcohol illegal actually created many opportunities for people who had never before been involved in the liquor trade. Women who produced illegal alcohol took their economic futures into their own hands, manifesting a side effect of Prohibition in the form of feminism and empowerment previously unseen in Colorado.

Changes in technology during the 1920s also boosted the access women had to new economic and social opportunities, including those around alcohol. The automobile most notably redefined the rituals of dating and courting, allowing many young and/or rural people to move about, free from the watchful eyes of chauffeurs or parents.11 Youngsters with freshly bobbed haircuts in places like Denver, Greeley, Boulder, and Colorado Springs spent evenings frequenting dance halls, sneaking in flasks of liquor on garter belts and drunkenly dancing the night away. Under this unprecedented sort of illegality, Coloradans experienced the first heterosocial mixing of genders in spaces involving alcohol. A realm that was previously defined as strictly males-only was now enjoyed thoroughly by men and women of all ages, and provided anonymous spaces for variant gender expressions. Because the people choosing to participate in the illegal consumption of alcohol were diverse, folks from strict or disapproving households could find comfort in an external space where they could relax and let loose. The fact that speakeasies, for example, were illegal meant that the social norms around gender exclusion did not exist. Because of Prohibition, women could for the first time in American history walk into a space mixed with various ages, genders, and cultures of people, and order a drink. New fashions in the 1920s also lent themselves to clever ways to smuggle alcohol. Ladies meeting up for a night spent dancing the Charleston with neighborhood boys would oftentimes smuggle large flasks in oversized fur coats and avant-garde styles of skirts and blouses.12 Women from both rich and poor families were caught at dances handing out flasks to dancers—another illustration that women eagerly participated in the new culture of illegal alcohol consumption.

The Denver Post described this “New Woman” who was flooding the state, often portraying her as a cigarette-smoking, alcohol-drinking, college-educated woman interested in politics. Women had equal suffrage, the new consumer economy was booming, and the moonshine seemed to flood the streets; because of Prohibition, alcohol was no longer a man’s-only fare. Colorado women redefined their social place in the world through their participation in illegal alcohol consumption and removed the taboo that only women of bad reputations enjoyed strong drinks and danced with boys. Even though mothers and grandmothers had been busy trying to protect youth by organizing to pass statewide Prohibition, their own daughters were the ones who rejected that law in every regard—contributing to a level of female-led crime never before seen in Colorado.

Prohibition agents bust bootleg shipments and a distillery, 1920s Colorado.

In this regard, law enforcement officials were deeply confused by the growing body of female criminals. Oftentimes, especially in the early years of Prohibition, women with illegal alcohol charges were let go with minimal punishment because they were deemed unable to have committed such crimes. For instance, Catherine Mucks was caught at a dance with a flask full of whiskey in Moffat County. At her court appearance, the judge let her go because her flask had a cockroach in it (which one can assume she plopped in once she knew she’d been busted). The judge said that such a drink was not fit for human consumption, and was therefore not for illegal recreational purposes.13 Sexist assumptions also allowed women to remain more anonymous than their male bootlegging counterparts. In 1921, a Grand Junction woman, only known as “PeeWee,” eluded both Colorado and federal law enforcement for charges of bribery and peddling booze within a large alcohol ring. Sheriff Frank N. DuCray and other officials raided and shut down the bootleg ring and stills, located in Palisade, Colorado. While all the male members of the illegal operation were arrested, PeeWee was never caught or even identified.14

Like the aforementioned pair of suit-wearing women from Creede, many Colorado women gained new money-making opportunities by moving alcohol around the state—whether alone, with other women, or with their husbands. Bada Olson was arrested in Colorado Springs along with her husband, Charles, for smuggling thousands of dollars’ worth of old, pre-Prohibition packaged whiskeys and spirits in their truck.15 Hidden beneath stacks of furniture was about 340 quarts of liquor and thirty gallons of assorted alcohol. The Olsons were poorer farmers in the area who likely figured they could make a few extra bucks driving some cargo around the state. They claimed they never drank it, and didn’t realize it was illegal, since it was from a pre-Prohibition stash. According to law enforcement, they were actually connected with an international whisky-running gang operating between the Mexican border and Colorado Springs. The couple received federal charges and were sentenced to prison time for their crime, although Bada got a significantly shorter prison sentence than her husband. Meanwhile, police bragged that they had placed the various bottles of Bacardi, Pearson’s Gin, Lawson’s Old Scotch, barreled whiskey, and other “long-forgotten brands” behind a locked jail cell. While the Olsons were being held in a Denver jail before their trial, newspapers provided the interesting news that all the confiscated liquor had managed to disappear from behind the jail cell where it had been locked away. Although officials were never able to produce the liquor itself for the trial, Bada’s husband was sentenced to three years in jail for transporting it but Bada was released without charges.16

While at this point it was clear that women were just as capable as men when it came to concocting illegal schemes surrounding alcohol, they were still serving much milder sentences. Such a fact points to an ongoing cultural perception of women in Colorado through the 1920s as being incapable of making illegal decisions, or unable to make public decisions for themselves. Instead, sentences given out to women who broke Prohibition laws hearkened to the idea that they were merely victims of their circumstances, rather than active and knowledgeable participants in the illegal market of alcohol, as men were. This bias inherently allowed women to be more successful in their illegal endeavors, as suspicion and prosecution were minimally targeted against them.

On the other side of Prohibition, women also benefited from new employment opportunities around the enforcement of the dry law—especially because female police officers could aid in rooting out the elusive feminine side of the bootlegging trade. Officer Edith Barker was Denver’s first and only fully accredited woman police officer; according to the June 10, 1928, edition of The Denver Post, “officers never made a raid without taking Mrs. Barker along to deal with the women, she was fearless in the work”.17 After formal revolver training she quickly became one of the best shots in the squad. She also received training in jiu-jitsu, which she reportedly used often, as she was known for tackling bootleggers who tried to flee from arrest.18 In numerous reports from across the state, Barker was best known for seducing men she suspected of being bootleggers or “mashers,” as well as using her skills to root out female bootleggers; she was very often successful in these endeavors. For example, in 1926, law enforcement had been baffled by a certain group of Denver-based bootleggers for six months. Officer Barker eventually arrested a woman who’d been acting peculiarly on street corners—an arrest that solved a months-long riddle. Police had spotted the woman around the city multiple times, always carrying her baby; but when Officer Barker approached the woman, the blanket on the baby slipped, revealing it instead to be a gallon of whiskey she was bringing to a buyer.19 Clearly, to most police officers the image of a woman carrying a child was the furthest thing from a lawbreaker; but Officer Barker’s clever police work proved smarter than the bootlegger bargained for. Law enforcement was still catching up with the ways in which women navigated their unique and often misunderstood abilities to perform illegal actions in public.

It is important to note that the appointment of Ms. Barker as the first female police officer in Denver came through promotion by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which fundraised for her salary for the first two years of her service to the city.20 The state of Colorado withheld payment to Barker for those first two years because she was a woman. It was the political power of the tireless WCTU women that allowed her to make history, paving the way for other women to serve in policing roles throughout the state thereafter. Officer Barker spent several years working for the Prohibition squad, making important arrests, but a reprimand came when she drove her own car to Golden along with another officer during work hours. She claimed that they’d been acting on a reliable tip to find bootleggers, but because of the infraction the force demoted her to the domestic crime squad nonetheless. Barker assisted the city with domestic issues until the mid-1930s.

In many ways, Colorado women actively participated in the entire process of Prohibition in Colorado—from campaigning, to passing the law, to bootlegging, drinking, smuggling, and even efforts to repeal Prohibition. Women’s actions shifted the strictly gender-segregated social spaces of Colorado into places of increased equality for socializing and leisure. When Prohibition was finally repealed at the federal level in 1933, newspapers published headlines declaring that women were seen in public, “Drinking Beer Openly and With Gusto.”21 Women had played widely publicized roles in both the legal and illegal sides of Prohibition, yet still people were shocked that they were daring to drink in public.

Despite that shock, however, the culture around gendered, public alcohol had changed, in a way that we still see in our day-to-day lives. Not only was Prohibition unsuccessful in any intended way, it instead helped to completely transform the women of Colorado into more independent and publicly acceptable figures, allowing them greater social freedoms. With such a monumental shift in ideology, and given women’s open participation in the experiment of Prohibition, Colorado fundamentally began a cultural, statewide shift from religious-based purification of society and behavior to a more socially equitable, modern state. These shifts appeared on both sides of the coin: women forged new paths through both legal and illegal means because of the illegality of alcohol. The bravery, innovation, and, yes, gusto, with which Colorado women blazed new trails during Prohibition are remarkable for a state where it had been illegal for women to buy a drink since 1901.

The path from high-collar, strictly gendered Victorianism to the modern rights and freedoms for women that we know today has been an uncertain one, yet our state’s behavior during Prohibition shows that we have always pushed against the status quo. Colorado women in the 1920s fought: they fought against alcohol and bootleggers, they fought against Prohibition, but most importantly, they fought against cultural assumptions that they couldn’t fight against anything at all.

NOTES

1. San Juan Prospector, March 15, 1918.

2. Katherine Harris, “Feminism and Temperance Reform in the Boulder WCTU,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, vol. 4, no. 2 (Summer 1979), 20.

3. Thomas J. Noel, The City and the Saloon: Denver 1858–1916, 2nd ed. (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 1996), 112.

4. Unidentified newspaper clipping, Shafroth Family Papers, FF23. Denver Public Library, Western History Collection. Also Harry G. Levine and Craig Reinarman, “From Prohibition to Regulation: Lessons from Alcohol Policy for Drug Policy,” The Milbank Quarterly, vol. 69, no. 3, Confronting Drug Policy: Part 1 (1991), 462.

5. Gail Beaton, Colorado Women: A History (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2012), 184.

6. Elliot West, “Cleansing the Queen City: Prohibition and Urban Reform in Denver,” Journal of the Southwest, vol. 14, no. 4 (Winter 1972), 332.

7. Ernest Cherington, The Standard Encyclopedia of the Alcohol Problem, 658.

8. Newspaper clipping, April 1924. Melrose Scrapbook, Denver Public Library, Western History Collection.

9. Newspaper clipping, Melrose Scrapbook.

10. Steven Mintz, “Statistics: The American Economy during the 1920s,” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of History, accessed May 5, 2019. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/content/statistics-american-economy-during-1920s.

11. Paula S. Fass, The Damned and the Beautiful: American Youth in the 1920s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 311.

12. The Spotlight, East High School newspaper, vol. II, no. 1 (April 15, 1925), 1.

13. Moffat County Bell, vol. 6, no. 31, November 4, 1921.

14. Montrose Daily Press, vol. XII, no. 206, March 4, 1921.

15. Colorado Springs Gazette, October 13, 1924.

16. Newspaper clipping, Melrose Scrapbook.

17. The Denver Post, June 10, 1928, 13.

18. The Denver Post, March 6, 1921, 43.

19. Aspen Daily Times, January 6, 1926.

20. Cherington, The Standard Encyclopedia of the Alcohol Problem, vol. 2, 667.

21. The Denver Post, April 7, 1933.