Story

Agnes Wright Spring

Author. Historian. Advocate.

During my years in public life I always worked harder than my staff and tried to justify the confidence placed in me by the nine governors whom I served, regardless of politics. I thoroughly enjoyed my work for more than half a century in a Man’s World—or since I worked in Wyoming and Colorado perhaps I should say—in a Women’s World, too!

—Agnes Wright Spring

Agnes Wright Spring was an author, a suffragist, and a historian. On one hand, her impressive career can be attributed to her tireless work in the fields of applied history and the history of the American West as an author and education advocate. On the other hand, as a woman who refused to be defined by the gender stereotypes of her day, her tenacity and determination served her well in these and other endeavors. Among other roles throughout her career, Spring held the positions of State Librarian of Wyoming, director of the Federal Writers’ Project in Wyoming, and State Historian of Colorado. Additionally, she authored over 500 articles and twenty-two books on topics surrounding the history of the American West.

Her efforts represent the dedication of a well-educated, socially in-tune woman who wanted to change the trajectory of history—as well as history as a discipline. As a woman studying and writing about history in the early twentieth century, Spring challenged the boundaries of traditional “Man’s World” practices, forged a path for other women in the field, and shaped the public’s perception of western history for years to come through educational programs and written publications. But her work has garnered relatively little recognition.

The Wrights’ two-story log home, about 1909.

Agnes Wright was born in Delta, Colorado, in 1894. She was the second of four daughters born to Gordon L. Wright and Myra May Dorset Wright. Her parents were wholesale fruit shippers, and Spring remembered riding in wagons full of apples. In 1903 the Wright family moved to Little Laramie River, Wyoming, and operated a stagecoach stop from a two-room log building. Myra and her daughters helped run the stage stop by greeting travelers and arranging household affairs. Spring specifically was in charge of raising chickens and cutting ten-cent portions of tobacco to sell to travelers.

The Wright family and their neighbors near the stage stop petitioned for a post office in the vicinity. Gordon Wright “wrote to Washington,” asking for authorization to set up a United States Post Office on his property. Granted permission, he named it the Filmore Post Office and appointed his wife, Myra, as postmistress. The tiny post office was barely large enough to hold packages. Spring referred to it as a “doll’s house” in her 1974 publication, “Stage Stop on the Little Laramie.” After a few years, Gordon built a two-story log home for his family and expanded his business to include dude ranching.

With the stagecoach stop, post office, and ranch, the Wrights now had plenty of company. It was through her interactions with their visitors that Spring developed her love of narratives and writing; travelers always had stories to share, and Spring recorded them in her journal. In her book Near the Greats, she looked back on these memories with fondness. She credited those evenings with inspiring her as a writer and instilling in her an appreciation of the West.

Spring could read from a young age and enjoyed learning in school. She and her older sister, Lucille, went to grade school in Laramie and boarded with local families during the academic year. Spring excelled academically, starting school at a third-grade level and quickly moving up to preparatory school—the same year as her sister, who was two years her senior. According to records in the Wyoming State Archives, after only three years of taking high school level classes at the Laramie Preparatory School, Spring submitted an application to the University of Wyoming. The university accepted her, and she started college courses at just fifteen years of age. Though it was not uncommon for students to take university courses at younger ages at that time, Spring's ambitious study habits propelled her forward into a four-year degree.

Young Agnes Wright and her sister, Lucille.

At this point in her life, Spring was determined to become a topographical draftsman and enrolled in engineering courses, becoming the first woman to do so at the University of Wyoming. She had been introduced to mapmaking by a traveler at her dad’s stagecoach stop, and was interested in the process of charting land. However, Spring quickly learned that being a woman and doing field work did not mix conveniently. The tools of the trade did not complement Spring's attire, as she soon realized that her steel corset caused the compass to give incorrect readings. Though she persisted in her courses, fellow classmates dubbed her “Old Ironsides.” She adjusted her outfits for her engineering classes, and continued on with her major.

Spring was able to pursue engineering because diverse educational paths were more readily accessible to women in the West. She enrolled in engineering college courses with ease, even though it was a male-dominated field at the time. All it required was proof of her prerequisites from preparatory school. Spring found ways to get around the socially accepted dress code for women while doing field studies. She was not forced to withdraw from the course based on her sex and the gender stereotypes of the time. Opposingly, women in eastern states did not enjoy access to courses and occupational training in fields that were deemed masculine. Women in the East were barred from most engineering, law, mathematics, and science courses because of their gender and the understanding that their place was in the home and not in a professional field.

Spring was fortunate to grow up in two western states that allowed women the right to vote in larger numbers than their eastern counterparts. Wyoming granted women the right to vote and hold public office in 1869, before it gained statehood. (Honorable mention goes to Utah. Although Wyoming Territory was first in the nation to grant voting rights to women in December 1869, Utah Territory did so several weeks later, on February 12, 1870. Since Utah held municipal elections and a territorial election before Wyoming did, Utah women earned the distinction of casting ballots first.) Other territories, such as Utah, Colorado, Washington, and Montana, followed close behind by letting women vote in different capacities. When Wyoming was added to the Union in 1890, it became the first state to allow women to vote. Colorado, coming in second, held a referendum and passed a women’s suffrage law in 1893.

Though romantic ponderings of the West rarely conjure progressive images, Colorado and Wyoming were radical in their decisions to allow women voters before 1900. Suffragists across the country, including Susan B. Anthony, noted that “men in the West were more chivalrous than men in the East.” Spring grew up in a society that largely viewed men and women as legal equals, which was not the case in the majority of other states. This is not to say that women had achieved equality in Colorado or Wyoming—far from it. However, during the late 1890s and early 1900s when Spring was growing up, Colorado and Wyoming were relatively progressive states.

Spring's understanding of women’s equality was shaped by the environment in which she grew up, and it greatly affected her perception of the world. Along with many women in the West after the 1890s, she believed she had the legal right to do anything a man could do. While this had societal limitations, it did not hold her back from entering male-dominated courses or professions. Spring was passionate about mapmaking and writing, both positions that were typically filled by men. She did not really perceive herself as breaking barriers, though, because she had the legal right to work alongside the men in her fields, and her position of equality allowed her to pursue her interests as she believed all women should be able to do. However, as Spring would later find out, this was not the case across the nation.

While in school, Spring continued her love of story-sharing by working in the campus library and writing for the Wyoming Student, a university publication that featured student authors and campus news. After publishing a few articles, Spring was introduced to the editing process by a fellow student author. She became heavily involved in editing the publication until she finally took over the position in the fall of 1910, becoming its first female editor. As a freshman, Spring was hired as an assistant librarian at the University of Wyoming by Dr. Grace Raymond Hebard. This four-year position, and the mentoring that came with it, changed the course of Spring's future. Dr. Hebard was the library’s founder and head librarian. She was also a professor at the university, a Native American historian, and a suffragist. As assistant librarian, Spring gained practical experience and formed a personal relationship with Hebard, who encouraged her to pursue her affinity for story-sharing, writing, and history.

Spring's experiences at the University of Wyoming essentially prepared her for two very different careers. While she passed the Civil Service Examination in 1913, which certified her mapmaking abilities, Spring found herself torn between the world of story-sharing and the world of charting. Interestingly, both options could be considered as ways of remembering. Mapmaking gathered tales of people and growth through distances and destinations, and presented them in a visual landscape. Nonfictional writing also featured collected stories, but presented them in much different ways. Spring decided to follow her research instincts, and Hebard’s advice. This choice changed the trajectory of her life’s work.

After working a few years in the Wyoming Supreme Court Library, Spring went on to accept a spot in the 1916 class at the Pulitzer School of Journalism at Columbia University. She moved to New York City and was recruited for the suffrage movement. Her mentor, Grace Hebard, was a well-known suffragist and helped Spring get connected within the group. When she didn’t have class, Spring knocked on doors, distributed pamphlets, and collected petition signatures. She wrote about having witnessed wildly different reactions to the idea of women’s suffrage, from doors being slammed in her face to having several women hug her. One day, Spring was knocking on doors when a woman yelled, “I hope you never get the vote!” Spring replied, “I have the vote. I am from Wyoming.” These contrasting reactions left their impression on Spring, who grew increasingly aware of the society in which she was now living—a less equal one than she had known.

Having grown up in the first two states that allowed women to vote, Spring was consequently unprepared for how different life was in New York. In the late 1890s and early 1900s when Spring was growing up, she had never questioned her legal right, or her civic duty, to participate. Spring had, no doubt, heard about suffrage movements in other states through her education; but being aware of something and experiencing it are two very different things, as Spring found out.

Two stories best exemplify Spring's formative experiences with gender discrimination. During her first year of journalism school, Spring wanted to take a constitutional law class so she could write articles about the suffrage movement. She went to the dean of the law school’s office at Columbia University, where she waited patiently and watched for more than three hours as male students were called in. Then, the secretary came out from behind the desk and said it was closing time, locking up the office as Spring sat there. Spring came back the next day and, after waiting for another two hours, demanded to be seen. When she was finally allowed to speak with the dean, she informed him that she was very interested in joining the constitutional law class. He curtly replied, “My dear young woman, we have not yet reached the enlightened stage of admitting women to our law school.” Spring left very disappointed in the state of affairs at Columbia University, and the experiences that followed did not help the situation.

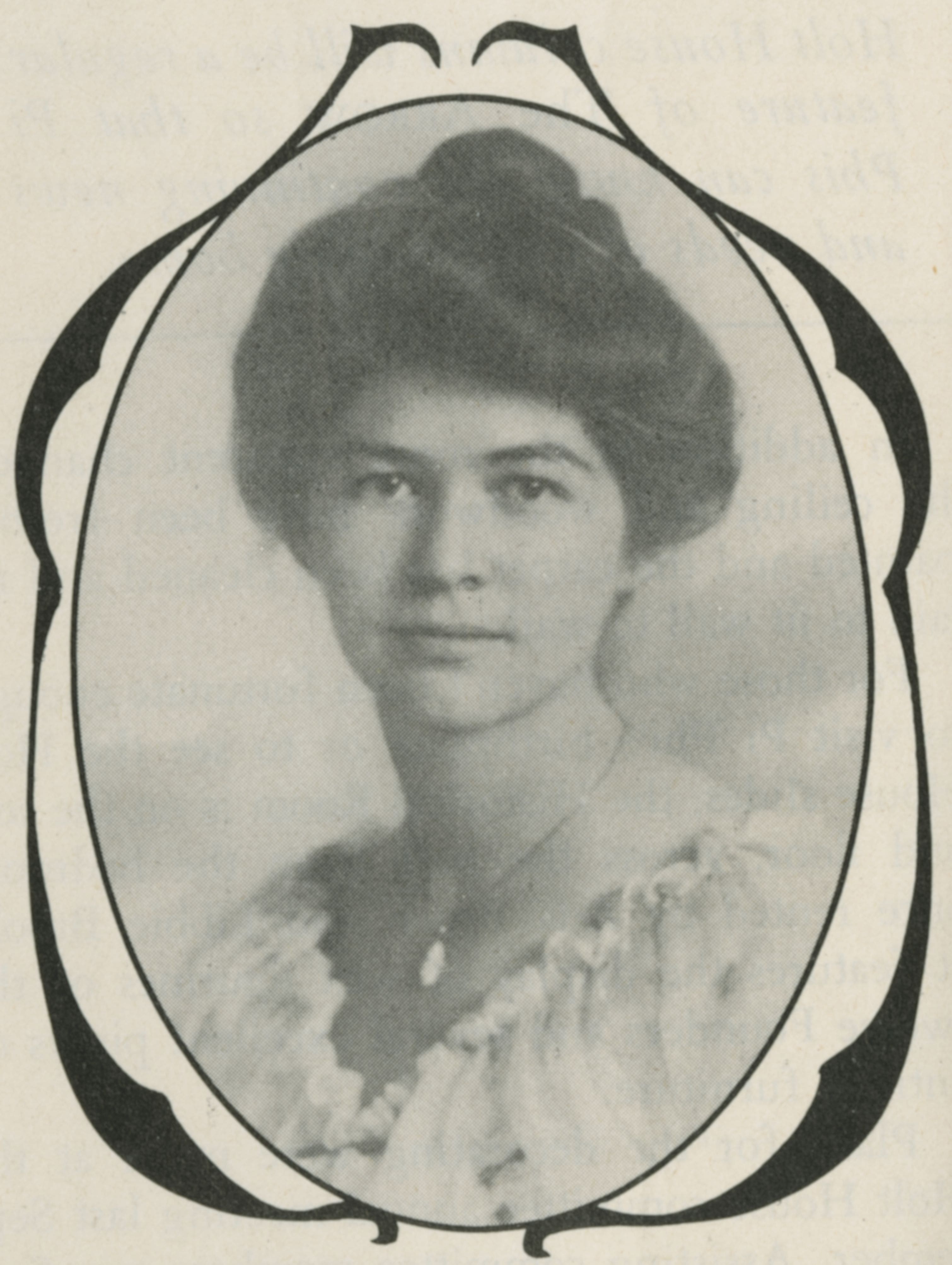

Agnes Wright Spring as a young woman.

In 1917, a male colleague of Spring's was offered a job at the New Bedford Standard but couldn’t accept the position because he was called to war; he recommended Spring for the job and sent her to interview. Prior to her interview, he gave her all the details of the position, including his promised pay. Spring, who was more than capable, interviewed and was offered the job—but at ten dollars a week less than her male counterpart. She was outraged. Spring refused the position and told the hiring manager that she was going back to the West, where they treated women the same as men.

Spring indeed returned to the West. She never completed journalism school, but her experiences there changed her. She brought what she learned back to Wyoming, where she was hired as the State Librarian in 1917 and appointed as State Historian in 1918. As Wyoming State Historian, she was known as a woman of “tireless efforts” who “devotes herself to literary detective work.” Her main job was to record the movements of Wyoming servicemen during World War I. She held the position until 1920.

Over the next twenty years, Spring refused to let her career get sidelined. In 1921, she married Archer “Archie” T. Spring, a geologist from Boston, and moved with him to Fort Collins, Colorado. At twenty-seven years old, she was older than most brides, and in her writings she recalled how she decided not to follow the housewife lifestyle. Both Spring and her husband continued their careers after their marriage and never had any children. During the 1920s, Spring published nearly seventy-five magazine articles and many short stories in publications such as the Wyoming Stock-Farmer, The Post, and Sunset Magazine. She focused more on stories about pioneers in western history, and found that they sold more regularly than her previous work. Spring also published her first book, titled, in the language of the times, Caspar Collins: The Life and Exploits of an Indian Fighter of the Sixties, in 1927. Collins, as Spring understood it, “played a great part in the settlement of the West” by commanding Fort Laramie during the Civil War and contributing to the study of Indigenous tribes and their languages. The book was a success, showing that Spring had mastered her writing style.

Drawing gaily bedecked Indians riding down imaginary trails was a favorite pastime of the boy, Caspar Collins…. Little did he dream, as he drew or painted, that some day a fort, a frontier town, a mountain and a stream in Wyoming would bear his name….

—Agnes Wright Spring, Caspar Collins: The Life and Exploits of an Indian Fighter of the Sixties, 1927

Only the Great Depression could slow Spring's momentum. Many publishing houses struggled during the 1930s. The Works Progress Administration (WPA), created to aid struggling workers during the Great Depression, initiated the Federal Writers’ Project in 1935 to help underemployed authors and historians. Each state set up a Federal Writers’ Project headquarters within the WPA state office, selected a director, and started hiring researchers, ethnographers, and writers from across the state. The purpose of the project was to put professional writers to work by paying them to write histories and guidebooks for their state. These books aimed at rejuvenating tourism to help the country bounce back from the Depression.

Dr. LeRoy Hafen, Colorado State Historian, was named director of the Federal Writers’ Project in Colorado and wanted Spring on his team. He had been following Spring's work over the previous few years, and the two ran in similar social circles. Hafen wanted to hire researchers and writers who were willing to go the distance to capture stories from every part of the state. He knew Spring was thorough and hardworking. In the fall of 1935, Hafen called Spring out of the blue and offered her a research position with the Colorado Federal Writers’ Project. Spring was thrilled and immediately accepted. However, her bubble burst when the State notified her that she was ineligible for the job. According to the State of Colorado, Spring was not poor enough to receive the aid, as it was a WPA-funded position. Hafen was frustrated by this setback, but his hands were tied.

Spring was disappointed but not out of hope or options. She utilized her whole network to sell her written work and brainstormed more ambitious pieces. Records in the Wyoming State Archives indicate that she compiled a proposal for a comprehensive narrative of Wyoming’s history—one with topics no one had ever studied before. She wanted to study the women of Wyoming, who, as she wrote, “accepting equality as a matter of course, have taken their place side by side with the men in building up a great western empire. Theirs is a story of courage, of isolation, of struggles and privations, of political intrigue, of initiative and leadership, of national recognition—filled with romance and color.”

Spring drew up a brochure on this idea and dropped it off at every academic institution she could think of, including the State Library of Wyoming. She happened to be visiting the library to do some research for another article when a new librarian, who did not work under Spring when she was State Librarian there, saw potential in the pitch. The librarian passed the brochure on to the Wyoming Department of Education, where the education committee and the Wyoming State Librarian reviewed it. Both parties agreed that Spring's project was important and well-developed enough to be part of the Wyoming Federal Writers’ Project mission.

Three weeks later, after the WPA had reviewed the Wyoming State Librarian and Department of Education’s plea to hire Spring for the Wyoming Federal Writers’ Project, Spring received an appointment notice. Not only was her book proposal accepted, but she was also being offered the position of director of the Federal Writers’ Program in Wyoming. Elated and a bit surprised, Spring readily accepted. She did not downplay her excitement or pride in having been offered an equal position to that of her colleague, LeRoy Hafen, a career shift that she did not take for granted.

Spring moved to Cheyenne in the spring of 1936, where she pursued her research goals and fulfilled other requests from the State with a team of eager researchers, writers, historians, and artists. Together, they compiled a list of counties, towns, cities, historic sites, and points of interest in Wyoming per the instructions from the national WPA office in Washington, DC. She admitted to deviating a bit from the national Federal Writers’ Project instructions, though, as she found them too limiting for her research aims. Instead, she arranged for researchers to scour the archives and libraries in Cheyenne and Laramie for existing information about pioneers, statehood, women’s suffrage, ranching, and historic battles. She then instructed the researchers to piece together what they did not know by conducting interviews and oral histories all over the state, gathering firsthand accounts from several communities that were historically underrepresented. Spring's team produced three books, The WPA Guide to Wyoming: The Cowboy State, Wyoming: A Guide to Its History, Highways, and People, and Wyoming Folklore: Reminiscences, Folktales, Beliefs, Customs, and Folk Speech. All were published in 1941, after which Spring set her sights on publishing more of her own writing and working with educational institutions.

We simply could not believe our eyes. None of us had ever thought much about folklore and when we received an index to folklore subjects listing “Animal behaviors and meanings, such as rooster crowing, dog barking, cattle lowing, etc.,” we thought it was the biggest piece of malarkey we’d ever seen.

—Agnes Wright Spring, circa 1936, quoted in Wyoming Folklore

Soon after, Spring moved back to Denver, when she accepted a position as assistant librarian at the Denver Public Library. Her time in the library reignited her passion for history and historic collections, and Spring published three books: William Chapin Deming of Wyoming: Pioneer Publisher, and State and Federal Official: A Biography, The Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage and Express Routes, and Seventy Years: A Panoramic History of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association. Spring also started collaborating on articles for The Colorado Magazine and eventually became editor of the publication in 1950. She was the first woman to do so.

The Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage and Express routes [carried] thousands upon thousands of passengers, tons upon tons of freight and express, and millions of dollars worth of treasure.

—Agnes Wright Spring, The Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage and Express Routes, 1949

The network of historians that Spring regularly worked with was steadily growing. They respected her detail-oriented research and audience-friendly writing style. Though Spring's books and articles were considered easy reading, they did not lack responsible and thorough research. LeRoy Hafen, then the State Historian of Colorado, recognized the promise of Spring's career. He and Spring had previously collaborated on The Colorado Magazine, and he asked her to take over for him as State Historian while he was away on a year-long fellowship at the Huntington Library in California. She accepted and became Acting State Historian of Colorado in January of 1951. Through this opportunity, Spring became the first female State Historian of Colorado, where she oversaw the functions of the State Museum (at that time located at Fourteenth and Grant Streets in downtown Denver), edited and published The Colorado Magazine, maintained the historic collections of the museum, and helped run the Colorado Historical Society (today’s History Colorado). The opportunity catapulted Spring into the public gaze, and she worked diligently to do her best and prove herself.

I think it is fine that you can write the fiction stories, too, but to my mind the true stories outshine the fiction these days.

—Agnes Wright Spring, in a letter to Colorado Pen Women, circa 1959

Because she was Colorado’s first female State Historian, Spring cared about how she was perceived by the public. Following World War II, the nuclear family ideal gripped the United States. Highly educated women were not the norm. According to the US Census Bureau, only 3.8 percent of women earned or were earning college degrees in the 1940s. Having a woman in a public and academic position was even more unusual. As State Historian, Spring consulted with many Colorado legislators about budget decisions and statewide events. She was required to advocate for the Colorado Historical Society and the importance of history to the state, and she kept those discussions and propositions as politically neutral as possible.

Regardless of her efforts, Spring had to navigate highly politicized topics, such as funding for history programs that welcomed all races and petitions to expand the staff by hiring more women, with authority figures who sometimes questioned her ability because she was a woman. In one instance, Spring had to petition for her own ability to oversee a mail order filmstrip program she, herself, had designed. Spring did not want to be petty, but also wanted to stand up for herself. She penned a pointed letter to the president of the Colorado Historical Society, James Grafton Rogers, and made copies for legislators who supported the program’s funding initiatives. She eventually was given the go-ahead to manage the program.

Additionally, as State Historian, Spring received dozens of letters from the State Capitol addressed “Dear Sir,” even after she had been announced in the position. Nonetheless, Spring persevered. She worked hard to respond to all public requests, whether it be to review a book in The Colorado Magazine, find a photo for someone’s family tree research, or oversee a budget for an important event. (Once, second grader Anna Hawthorne of the Cheyenne Mountain School wrote for help with a history project on Bent County. Spring replied with fifteen pages of information and nearly a dozen copies of photographs.) As a result, Spring was well received by the public and her colleagues.

Executives at the Colorado State Museum and the Colorado Historical Society, such as historical society president James Grafton Rogers, appreciated Spring's work ethic. They created the Executive Department of the State Historical Society, which oversaw the financial and program planning of the museum. With this new department came a new position, Executive Assistant to the President. Following LeRoy Hafen’s return as State Historian in September of 1951, Spring was chosen as the executive assistant. She left the position in 1954 when she was unanimously chosen as State Historian.

During the years that Spring served as State Historian (1954 to 1963), she advocated for the expansion of history curriculum in Colorado schools. She used her position to collect historic artifacts and photographs that would benefit visitors to the State Museum and students. She worked with the Department of Transportation to add bus lanes next to the State Museum in order to allow schoolchildren to safely unload. Spring also oversaw a program called Junior Historians, in which students of all ages submitted short written pieces about something in history they had studied, whether it be a topic in school or an artifact at the museum. Spring helped the students conduct responsible research and edited their writing, selecting a few to publish each year in the Gold Nugget. This student-authored publication was well-supported by Colorado teachers, who advised their students to submit pieces.

Additionally, Spring was a believer in the inclusion of technology in history and schools. As State Historian, she helped fund a project that created dozens of filmstrips of Colorado artifacts that were exhibited at the museum and lesson plans to accompany them. Through the mail, these filmstrips were available to schools across the state for a small rental fee. Her goal was to reach as many children as possible, including those who couldn’t come to the museum, and to encourage them to write about history. She accomplished this through the filmstrips but also through television and radio programs. Spring participated in several educational TV programs that took viewers on a special tour of the State Museum’s exhibits. She was also featured in dozens of radio interviews on local Denver stations about new exhibits, museum events, and The Colorado Magazine. She informed teachers about these broadcasts in hopes that they would assign listening to the radio or watching the TV program for homework; she worked hard to encourage the inclusion of more history into the state’s school curriculum.

Though Spring's overarching goal was to expand historical learning for all students, she sometimes found it necessary to emphasize that this included female students. One notable example of this happened live on the air during her time as Colorado State Historian. In a 1958 radio interview on KFG Radio the host, known as “Sergeant Y,” asked Spring if she had any advice for boys hoping to write their own stories. Although transcripts of interviews alone cannot bear witness to the host’s tone or intent, Spring's response made everything clear: “I encourage all students to keep their interests alive by writing often and reading western history.” Without being too harsh, Spring advocated for female students among the hopeful future writers. It would have been easy for her to let something like this go, but she did not.

Spring was not only an advocate for girls becoming historians and writers, she was an example of it. From the 1940s to the 1970s, she published sixteen books while also contributing articles to the Denver Woman’s Press Club, the National League of American Pen Women Inc., the Colorado Authors’ League, the Western Historical Association, and the Western Writers of America. Somehow she fit research trips and writing time into her State Historian schedule. After she retired from her role as State Historian of Colorado in 1963, Spring continued to write and publish books, and she remained on advisory boards for the Colorado State Historical Society. Spring was inducted into the Cowgirl Hall of Fame in 1973 for her work on the history of the American West.

Writing for the Cheyenne Eagle, a young reporter once wrote that at 5’2”, Agnes Wright Spring was “one of the human landmarks of the Rocky Mountain Region.” Spring successfully connected history across state lines and professional fields, blending her career as an author with her career as a historian of the American West. She shaped her career to include her passion for history and writing. As author of twenty-two books and well over 500 articles, Spring was able to keep doing what she loved while also greatly contributing to the history of the American West, a powerful figure in Colorado in so many arenas.

Agnes Wright Spring was an advocate for women, history, and education. Programs she created as State Historian still exist today at the History Colorado Center. Collections she curated in Colorado and Wyoming still enlighten curious minds. She passed away in 1988, but her life’s work lives on in the extensive records she left behind and the impact she had on so many budding historians’ careers.

For Further Reading

Readers can get a sense of Agnes Wright Spring’s research and writing style by finding her earliest books, Caspar Collins: The Life and Exploits of an Indian Fighter of the Sixties and The Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage and Express Routes. See also Near the Greats, Agnes’s own record of her life through the lens of interviews she conducted.

Interested readers may enjoy Buffalo Bill and His Horses and William Chapin Deming of Wyoming: Pioneer Publisher, and State and Federal Official—A Biography. Many of Agnes’s oral history interviews are available online through the American Heritage Center, Laramie, Wyoming. Unfortunately, many of Agnes’s other works are out of print.

More from The Colorado Magazine

Understanding Amache: The Archaeobiography of a Victorian-Era Cheyenne Woman Composed around 1870, the photographic portrait of Amache Ochinee Prowers is a window into her complex world.

The Hues and Textures of a Lived Life: Bitterroot Memoir Wins the Barbara Sudler Award

“We Will Go Wherever We are Needed and Do Whatever Comes to Hand” the disCOurse is a place for people to share their lived experiences and their perspectives on the past with an eye toward informing our present. Here, a member of the Volunteers of America team recognizes an organization that’s provided more than a century of compassionate aid to communities in need in Colorado and throughout the nation.