A Shelter from Harsh Times

The African American Mountain Resort of Lincoln Hills

Though Colorado’s African American population avoided the most severe abuses of Jim Crow and segregation in the early twentieth century, they nonetheless experienced significant overt discrimination. They faced limited housing, employment, and recreation opportunities and lived under state and local governments controlled by the Ku Klux Klan for much of the 1920s. Still, Colorado’s African Americans flourished, building a strong community with thriving businesses.

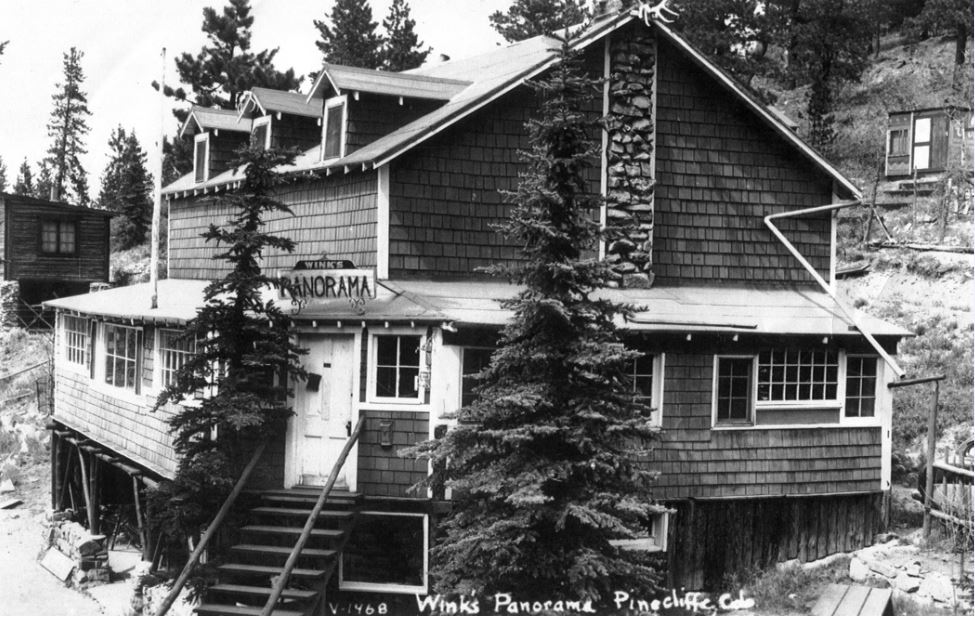

The black community’s economic strength allowed it to create Lincoln Hills, a little-known but historically important mountain oasis where they could relax and enjoy the Rocky Mountains’ natural beauty without the discrimination and segregation that permeated American life. Located in Gilpin County between the small towns of Pinecliffe and Rollinsville, Lincoln Hills offered early-twentieth-century blacks the opportunity to become landowners and participate in cultures of outdoor recreation and leisure that had historically been denied to them. The social hub of Lincoln Hills, Wink’s Lodge—a 3,100-square-foot, two-story, six-bedroom Craftsman-style building with vernacular Rocky Mountain elements—survives as the intact symbol of this enclave of African American culture.

“Lincoln Hills was a place that middle-class black people who had discretionary funds could go to vacation,” says Gary M. Jackson, a Denver attorney whose family has owned property at Lincoln Hills for three generations, in an article by Andrea Juarez in May 2007’s Denver Urban Spectrum. “From the point of view of my grandparents and own parents, this was a place of refuge, a shelter from harsh times. This was a place they could freely go and enjoy mountain life with family and friends.”

While early Lincoln Hills property owners came from Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas, New Mexico, and as far away as New York, Texas, and Florida, Lincoln Hills remained first and foremost a mountain colony of blacks from Denver, home to the great majority of Colorado’s black population. In 1920, Denver’s African American community represented a much smaller proportion of the population than African Americans in most southern cities or large northern metropolises such as New York or Chicago. Historians Stephen J. Leonard and Thomas J. Noel note in Denver: Mining Camp to Metropolis that Denver’s blacks had a significantly higher standard of living than did those in other major American cities. Colorado’s African Americans boasted high literacy rates and more than a third of its blacks owned homes, almost five times the percentage in New York State.

Writing in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s The Crisis, author and poet Jessie Fauset celebrated the state of relative prosperity and interracial harmony among Denver’s black population. “Out of the West comes the report,” she enthused in the journal’s November 1923 edition, “of 6,500 colored people who work and play and have their being side by side” with 250,000 whites, “and both races are content and happy. It is a relief, in the midst of such vexing racial problems, to read of such a Utopia.” Fauset’s article highlighted the strength of local black institutions, praised white allies of the Denver black community in government and business, and noted the achievements of blacks in white-dominated industries. “It is, however, in business enterprises manned strictly by colored people that our small racial group in Denver is to be congratulated,” Fauset wrote. The article enumerated many African American businesses operating in Denver, in diverse fields including real estate, mortgage lending, insurance, investments, mortuaries, taxi and baggage, hotels, and two “Elite Drug Stores, the only colored pharmacies between the Missouri River and the Pacific Coast,” which “enjoy the patronage of all nationalities.”

This upbeat report on the status of Denver’s black population in the 1920s belied some harsher realities. While racial segregation and inequality manifested themselves somewhat less egregiously than in other parts of the country, Colorado’s blacks faced pervasive discrimination and lived under the threat of a Ku Klux Klan–dominated government. The Klan, which The Denver Post in 1924 called the “largest and most efficiently organized political force in the state of Colorado today,” counted Denver Mayor Benjamin F. Stapleton, Colorado Governor Clarence J. Morley, and a host of other elected officials as members by 1925. Though many African Americans had settled on Larimer and Blake Streets northeast of downtown Denver in the late nineteenth century, surging white racism enforced by discriminatory real estate covenants pushed them farther east in the first decades of the twentieth century. Attempts to live outside the recognized black enclave in the city’s northeast corner often resulted in threats or violence, including cross burnings and house bombings.

Colorado passed a law in 1908 that extended to all citizens “full and equal enjoyment of . . . places of public accommodation and amusement.” However, as Moya Hansen notes in the spring 1993 edition of the University of Colorado Denver Historical Studies Journal, in practice the law was often violated. African Americans had to use segregated balcony seating at the prestigious Tabor Grand Opera House and other prominent performance venues. Although blacks in Denver had access to some public parks, swimming pools at Washington and Berkeley Parks remained off-limits. The city bathhouse and gymnasium were segregated, and African Americans were denied use of public golf courses and tennis courts. In 1932, 150 African Americans attempted to integrate the bathing beach at Washington Park in a predominantly white section of south Denver, resulting in a violent white mob attack on the swimmers, plus the arrest of ten African Americans and seven of their white allies.

It is little wonder that Colorado’s blacks sought to create a mountain Eden of their own, untouched by the bigotry and strife that tainted even their relatively tolerant state. The comparative prosperity of Colorado’s early-twentieth-century black community meant that it had the resources to make that vision a reality.

In 1922, Robert E. Ewalt and E. C. Regnier led a group of Denver black entrepreneurs in forming the Lincoln Hills Development Company (LHDC) to promote the creation of a black resort community in Lincoln Hills. Ewalt and Regnier worked in partnership with the Sayre ranching family of Gilpin County, who owned the land.

In September 1924, The Daily Camera reported that Fred Dungan, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Colorado in Boulder, surveyed “640 acres of land located two miles west of Pinecliff [sic] and six miles south of Nederland which is being made into a cottage resort for colored people to be known as Lincoln.” Lincoln Hills was subdivided into 594 lots. When lots were ready for sale in 1925, the LHDC published advertisements and brochures soliciting buyers. “LINCOLN HILLS: THE BEAUTIFUL,” read one such advertisement. “Nestled within the grandeur of the everlasting hills,” said the flyer, “bathed in perpetual sunshine and fragrant with the odors of wild flowers and the health giving pine forests, we are building a place that will attract thousands of people and at the same time show our genius and constructive ability.”

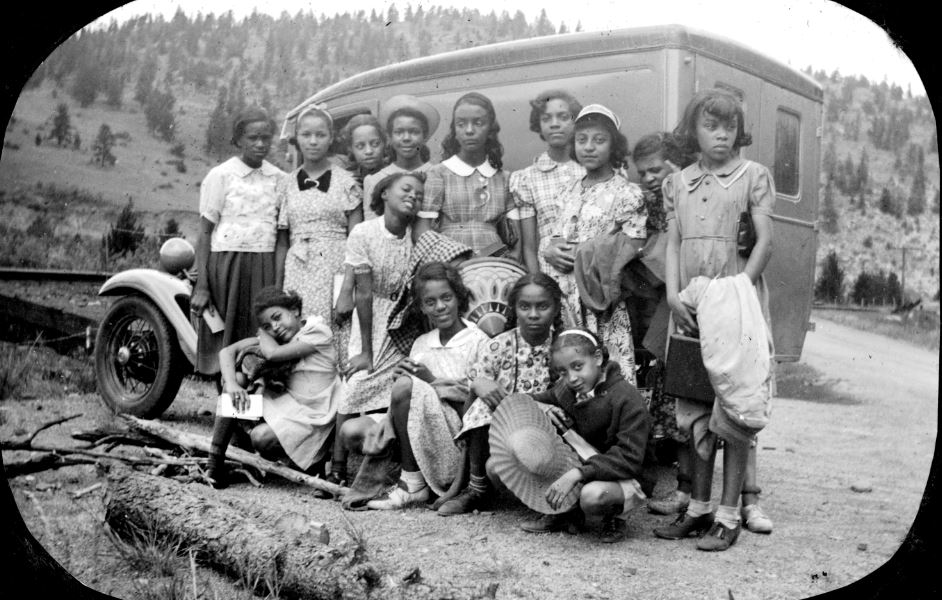

Campers arrive at the Lincoln Hills rail stop on their way to Camp Nizhoni in the 1930s.

African Americans could become Lincoln Hills landowners for as little as $50, with a $5 down payment and monthly payments of $5, reported historian Juarez for the Denver Urban Spectrum. The affordability of land at Lincoln Hills opened opportunities for Denver’s burgeoning black middle class, as well as for blacks from other parts of the country. Visitors reached Lincoln Hills either by automobile or train. The Denver & Salt Lake railroad passed through the Moffat Tunnel from both Boulder and Denver, stopping at Pinecliffe and again just down the hill from the Lincoln Hills development.

The LHDC received letters of endorsement in the mid- to late 1920s from many prominent African American and other residents of Denver, including leaders of churches and the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). “There is no segregation about it,” read a letter from Dr. J.H.P. Westbrook of Denver to Ewalt and Regnier, dated July 4, 1925, “only a chance to get a large acreage where we can go in peace and contentment, surrounded by friends and enjoy ourselves.” Pastor G. L. Prince declared in a 1926 letter that the “demonstration of our creative ability seems to me the greatest thing about this splendid project. We like the beauty, the climate, the fishing and the recreation of all sorts . . . but to point with pride to beautiful LINCOLN Hills as the product of our own creative genius is still more inspiring.”

Lincoln Hills also housed Camp Nizhoni, Colorado’s first dedicated camp for African American girls. The Phyllis Wheatley Branch of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) established the camp in 1925 and named it after a Navajo word meaning “beautiful.” Segregation prohibited the Wheatley Branch from using the camps and facilities of the Central Branch of Denver’s YWCA, and the African American girls had encountered transportation issues and hostility from white neighbors when renting other camping facilities near Boulder and Idaho Springs. The Lincoln Hills developers solved the problem by permanently deeding a tract of land with a house to the Phyllis Wheatley Branch at nominal cost, on the condition that they camp there for at least three consecutive summers. The camp typically hosted twenty to thirty girls at a time during two-week sessions each July. Campers slept in a dormitory, took six-mile hikes, sang camp songs, encountered mountain flora and fauna, and learned to “rough it” in the great outdoors.

Marie Greenwood, the first African American teacher in the Denver Public Schools system, spent almost every summer between ages fourteen and thirty at Camp Nizhoni, first as a camper and then as a nature counselor. “It was a place where we could hike, play games, swim, and learn about nature in an all-girl setting,” says Greenwood. “I loved every minute of Camp Nizhoni. I lived and breathed being outside.” Greenwood led the girls on “all-day hikes or . . . overnight outings where we slept under the stars,” she told Andrea Juarez in an interview for her 2007 article. “We’d start out early in the morning and cook a breakfast out on the trail. We’d make a fire and I’d have the girls heat the rocks then they’d blow off the ashes. I showed them how to cook bacon on the rock and then fry up an egg with the leftover grease. The girls were so hungry sometimes they didn’t care if there were ashes in their food.”

The structure on the far left appears to be the Camp Nizhoni Hotel, originally built as part of mining activities at the Pactolus Placer. In 1924, Camp Nizhoni began using it for staff lodging and a visitors’ hotel. In all, five of the mine buildings were repurposed for the camp.

As historian Modupe Labode describes in the June 2002 issue of Colorado History NOW, Camp Nizhoni operated throughout the 1930s and into the 1940s despite budgetary strain from the Great Depression and World War II. In the early 1940s, the Colorado YWCA began reexamining its segregation policies. In 1943, the Central Branch of Denver’s YWCA began integrating Camp Lookout, near Golden. By the summer of 1945, twenty-nine African American girls attended Camp Lookout along with their peers of white, Asian, and Hispanic origin. To save on maintenance expenses, the YWCA sold Camp Nizhoni in 1946. However, its legacy remains an important part of the larger Lincoln Hills story. A dirt road in Lincoln Hills is named Phyllis Wheatley Way, and several buildings associated with Camp Nizhoni survive today. Though the remaining buildings possess less historic integrity than does Wink’s Lodge, the area encompassing the lodge and camp buildings has been considered a potential National Register of Historic Places historic district.

According to census records, Obrey Wendall “Wink” Hamlet was born to Rosa Patton in Tennessee on April 27, 1893. By the time he filled out a draft registration card in June 1917, Hamlet lived at 2100 Arapahoe Street in Denver’s historically black Five Points neighborhood. According to Hamlet’s niece, Linda M. Tucker KaiKai, her uncle was an ambitious, hardworking youth who ran errands, cut grass, and did odd jobs to earn money. As he grew older, he worked as a bartender and a carpenter, skills that would prove useful later in life as builder and proprietor of Wink’s Lodge. Hamlet became a successful Five Points entrepreneur, owning an icehouse business, coal company, and moving company.

Hamlet, an original Lincoln Hills landowner, expressed his enjoyment of the mountain lifestyle in a January 24, 1928, letter to the developers:

It’s the keenest pleasure I have ever experienced. It thrills and fills me with love for the out-of-doors. My own cottage, built by my own hands, painted orange and trimmed in brown, nestled amid the evergreen trees, away from the smoke, noise and confusion of the city and where the air and water are always pure, fulfills my every desire for rest and recreation. I appreciate my lots and my cottage so much that I cannot but write you and express my appreciation of your efforts in supplying to me and our group of people the most wonderful mountain resort I have seen in Colorado... It is just what we want.

Beyond relishing his small cottage, Hamlet saw an opportunity at Lincoln Hills to create a dignified African American retreat. Beginning in 1925, Hamlet built his lodge with help from friends and relatives over the course of three summers. He used timber, stone, and other materials on hand at Lincoln Hills, as well as those salvaged from other structures including pressed metal ceiling tiles and wainscot from the original Denver Post building. Wink’s Lodge, also known as Wink’s Panorama, opened in 1928 and served for the next four decades as a weekend getaway for Denver’s black community, a destination for black travelers, and an informal nexus of African American culture.

The Great Depression hit Lincoln Hills hard. The LHDC’s scheme to make mountain land ownership affordable to a new demographic ran into trouble when many buyers became unable to keep up with the costs of owning a vacation property and abandoned their lots. However, Wink’s Lodge remained open, preserving the original vision of Lincoln Hills. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Hamlet advertised in Ebony magazine. A 1952 issue of Ebony featured Wink’s as part of a “Summer Vacation Guide” of destinations friendly to its readership. Vacationers could enjoy trout fishing, mountain climbing, and horseback riding at the daily cost of $3, including meals. Such national exposure drove interest in Wink’s African American oasis and brought more visitors from the eastern United States.

Alberta Hamlet and an unidentified friend pose, probably at Lincoln Hills. The building behind them is often mistakenly identified as Wink’s Lodge.

Visitors reaching Lincoln Hills by train enjoyed a relatively safe and dignified travel experience. Moya Hansen’s article reports that “Colorado railroads did not discriminate against blacks and the short trips they offered attracted black patronage.” For those who lived just thirty-four miles away in Denver, family car trips to Wink’s united different generations in a shared journey.

The hospitality at the lodge elevated it above and beyond a mere staging point for mountain recreation. As Barbara Lawlor details in the July 18, 1996, edition of the Nederland Mountain-Ear, “Wink” Hamlet welcomed visitors by often personally picking them up at the Lincoln Hills train station and driving them to the lodge. After socializing in the main floor living room, guests savored the renowned cooking of second wife Melba Hamlet. They could visit the dining veranda at their leisure and order fried chicken raised in the mountains behind the lodge, fresh trout from nearby South Boulder Creek, peach cobbler, and other delicacies from Melba’s kitchen.

For children, Wink’s Lodge opened a window to the natural world. In the 1950s, Hamlet’s niece and nephew often played guide to urban children visiting the lodge with their families. Linda M. Tucker KaiKai remembers:

Most of the children had never been to the mountains. They were not used to being out of their parents’ sight or going into the woods or getting dirty. . . . My brother and I . . . helped teach them not to be afraid of bugs and dirt and out-houses. We shared with them the joy of running up and down steep hills and finding pretty rocks with fool’s gold and listening to the birds and watching minnows in the stream and listening to the wolves and the owls at night. They would never forget the feeling of quenching that dry thirst with cold, sweet water from the river or of satisfying that deep mountain hunger with Aunt Melba’s fried chicken and honey biscuits. For these children, the holiday at Wink’s Lodge was probably the most enchanting experience they had ever had.

Wink’s Lodge also offered nightlife for adults, hosting cutting-edge musical and literary artists from the 1930s through the 1950s. Touring Big Band musicians who performed in Denver at venues such as Benny Hooper’s Casino Dance Hall on Welton Street and the Rainbow Ballroom on Fifth Avenue between Lincoln and Broadway often avoided the city’s segregated accommodations by staying at Wink’s. According to oral tradition, notable guests might have included musicians Duke Ellington, Lena Horne, and Count Basie, as well as writers Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. Spontaneous late-night jazz performances and private readings by Harlem Renaissance writers often enthralled Hamlet’s guests. After Camp Nizhoni closed, he bought one of the camp’s buildings and turned it into “Wink’s Tavern.” The tavern, just 100 yards down the road from the lodge, had a jukebox that played the latest 78 rpm records for a nickel and functioned as an informal performance venue for the traveling jazz musicians. Revelers danced, played cards, and drank beer or soda until 2 a.m. According to Niccolo Werner Casewit, a researcher for the Wink’s Lodge Advisory Board, “Wink’s Lodge has been likened to the literary salons during the Harlem Renaissance. Except this one is nestled in the mountains.”

Wink’s wife Melba Hamlet and Vivian Hooper pose at Wink’s Lodge, 1957. Melba’s fried chicken and peach cobbler were legendary among visitors. Vivian was the wife of Benny Hooper, owner of Benny Hooper’s Casino Dance Hall, a vital gathering place for jazz aficionados at 2637 Welton Street in the heart of Denver’s Five Points district.

Paradoxically, the demise of segregation meant the end of an era at Wink’s Lodge. Visitor traffic to Lincoln Hills declined as the Civil Rights movement demanded integration of whites-only facilities; in parallel, the appeal of an African American enclave faded. Wink Hamlet died in 1965, and by 1971 his wife had sold all of his Lincoln Hills properties. Longtime Lincoln Hills visitor John Scott recalls, “Lincoln Hills was old school to the younger generation who went to new areas like Vail. When Wink’s died, interest in Lincoln Hills died.” Only a few African American families kept their cabins after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 toppled the barrier of legal segregation.

While many Lincoln Hills structures fell into disrepair and were eventually razed, a series of owners preserved Wink’s Lodge, one of whom succeeded in adding Wink’s to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. In 2006, the Colorado State Historical Fund awarded a grant to the nonprofit James P. Beckwourth Mountain Club to purchase the lodge. The group, now known as Beckwourth Outdoors, intends to rehabilitate the property and reopen Wink’s Lodge as an outdoor education and events center that highlights the significance of the mountain retreat for African Americans during segregation.

The rustic appeal of Lincoln Hills and Wink’s Lodge endures for the African American families who came to vacation in peace. “I felt like royalty being able to rent a mountain lodge that set [sic] amid clusters of other cabins rented by colored people,” recalls Eugene Washington in a February 19, 2006, Denver Post article by Sheba R. Wheeler. Washington brought his family from the Mississippi Delta to experience the Rocky Mountain lifestyle. “We did not have to worry about entering and exiting under dubious, unfounded circumstances. We were going to WINKS, and that was all we needed to know.” A shelter in both the literal and symbolic sense, Wink’s Lodge stands as a reminder of the segregation era and the spirited, creative responses of Colorado’s resilient black community in the years before the Civil Rights movement’s decisive triumphs.

For Further Reading

For more about Lincoln Hills, Wink’s Lodge, and Camp Nizhoni, see Andrea Juarez’s “Lincoln Hills: An African-American Monument in Colorado’s Mountains” (Denver Urban Spectrum, May 2007), Modupe Labode’s “Off to Summer Camp” (Colorado History NOW, June 2002), and Moya Hansen’s “Entitled to Full and Equal Enjoyment: Leisure and Entertainment in the Denver Black Community, 1900 to 1930” (University of Colorado Denver Historical Studies Journal 10, No. 1, Spring 1993: 64). To learn more about the challenges African Americans faced in travel and leisure during the segregation era, see Jearold Winston Holland’s Black Recreation: A Historical Perspective (Chicago: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002), Perry L. Carter’s “Coloured Places and Pigmented Holidays: Racialized Leisure Travel” (Tourism Geographies 10, No. 3, August 2008: 265–84), Mark S. Foster’s “In the Face of ‘Jim Crow’: Prosperous Blacks and Vacations, Travel and Outdoor Leisure, 1890–1945” (The Journal of Negro History, Spring 1999), and Cotton Seiler’s “‘So That We as a Race Might Have Something Authentic to Travel By’: African American Automobility and Cold-War Liberalism” (American Quarterly, December 2006). For a contemporary look at blacks in 1920s Colorado by an NAACP activist, see Jessie Fauset’s “Out of the West” in The Crisis 27 (November 1923).