Story

Artworks that “Captivate the Viewer Quietly”: Colorado Artist Bernard Arnest

(25 minute read)

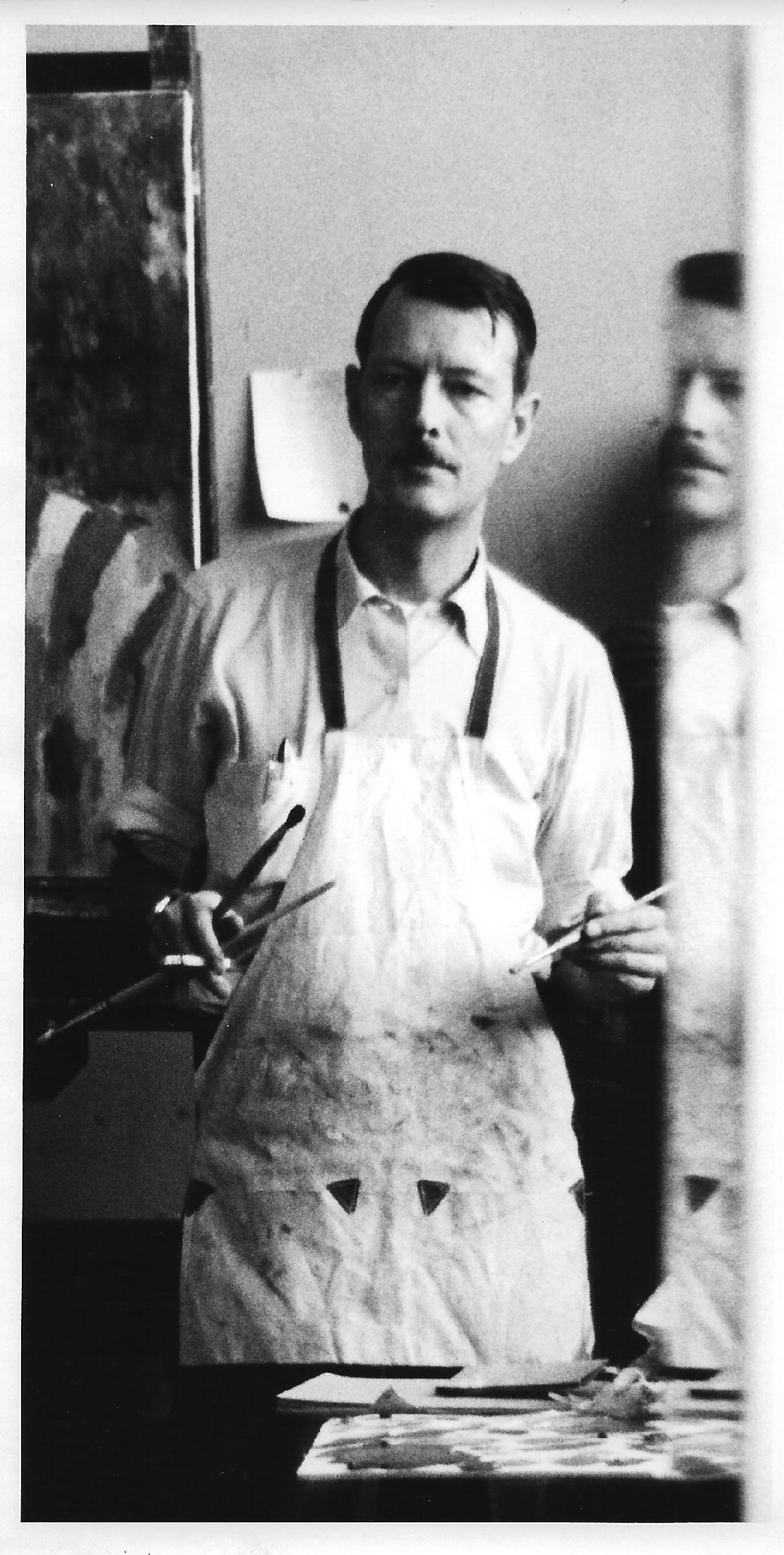

Over the past two centuries Colorado’s scenic and atmospheric qualities dominated by the Rocky Mountains have inspired many visiting and resident artists, both male and female, working in a variety of styles and media. While known during their lifetimes through exhibitions and attendant press coverage, their careers subsequently have not received much attention or documentation so that some of them have all but disappeared from public memory. The exhibitions of Bernard Arnest (1917–1986) this year in Colorado Springs at the Cottonwood Center for the Arts and the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College once again put the spotlight on Arnest—who worked for forty-plus years in Colorado and outside the state—and provide an occasion to survey his notable career.

A Denver native, Arnest attended East High School, where he studied with its longtime art teacher, Helen Perry. In the early 1930s her leading students included Eugene Trentham, Ethel and Jenne Magafan, and Edward Chavez, all of whom later enjoyed successful careers as professional artists. Herself a student of André Lhote in Paris, Perry for many years maintained a high standard in the Denver Public Schools that led to a number of her students winning the Charles Milton Carter Memorial Prize annually awarded to art students in Denver’s senior high schools.

In an undated Rocky Mountain News clipping provided by his family, Arnest credited Perry with his choice of art as a lifelong career:

I had the good luck to have a very unusual [art] teacher. . . . She was a little irascible, but she was very serious about art. She also had a background that had to do with the practice of art rather than just one of art teaching, like everyone else. At that point, art looked far less demanding and much more interesting than anything else to me.

Before attending East, Arnest wanted to study music, intending to become a pianist. However, in his high school drawing class he discovered his aptitude for art. At Perry’s recommendation he benefited from supplemental instruction at the newly founded Kirkland School of Art and at the school of fine art and design operated in downtown Denver by Colorado artist Frank Mechau, recently returned from a five-year sojourn in Paris.

The initial public recognition of Arnest’s artistic talent occurred at East when he was the first-place winner of the Charles Milton Carter Memorial Prize. He signed his work “Victor Kaelin,” a fictitious name as stipulated by the contest. The prize earned him a prominent place in an exhibition—along with fellow runners-up—at Chappell House, the first home of the Denver Art Museum. In his review of the exhibit in the Rocky Mountain News, curator of painting at the Denver Art Museum Donald J. Bear augured the young artist’s future career: “Thruout [sic] Arnest’s work there is an evenly sustained facility, a variety of technics and individual personality. . . . He has observed something for himself and there is sound and sane talent behind it.”

Following graduation from East, Arnest enrolled at the Broadmoor Art Academy in Colorado Springs, where he studied with Boardman Robinson and Henry Varnum Poor. Founded in 1919, the academy became the state’s leading art school in the first half of the twentieth century thanks to generous financial patronage and a faculty of nationally known artists such as John Carlson, Robert Reid, Birger Sandzén, Randall Davey, Ernest Lawson, Frank Mechau, George Biddle, and Ernest Fiene. They attracted a diverse student body, including a large percentage of women artists, and garnered national recognition for the academy from important American art centers in the East and Midwest.

Bernard Arnest’s egg tempera portrait of Boardman Robinson from the late 1930s.

Hired in 1930 to teach figure painting at the Broadmoor Art Academy, Boardman Robinson was appointed the following year as director of its arts school, a position he held until health issues forced him to resign as director emeritus in 1947. Early on in New York he had acquired a national reputation as an illustrator, muralist, and instructor at the Art Students League from 1924 to 1930. He strongly believed that any drawing should be dealt with as a composition just as seriously as a painting, a view also characterizing Arnest’s mature work as an artist. An instructor of exceptional ability at the Art Students League, Robinson stimulated students by giving them skills and techniques with which to express themselves. While Robinson’s student in Colorado Springs, Arnest painted an egg tempera portrait of his teacher.

Robinson’s enthusiasm invigorated the Broadmoor Art Academy, which in 1936 became the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center complete with a magnificent new building designed by Santa Fe–based architect John Gaw Meem. In addition to energizing the local art community, Robinson continued the process of inviting recognized American artists to teach there in the summers, when student enrollment peaked.

He also committed to the development of a good lithography department at the center, coinciding with the widespread national interest in the medium at that time. As Carl Zigrosser noted in The Book of Fine Prints: An Anthology of Printed Pictures and Introduction to the Study of Graphic Art in the West and the East (Crown Publishers, Inc., 1956),

[A] great stimulus to the expansion of graphic art [in America] came through the spread of the dynamic idea that printmakers could find their subjects close at hand, that their own way of life, their own background and distinctive customs could furnish esthetic material of a most exciting kind.

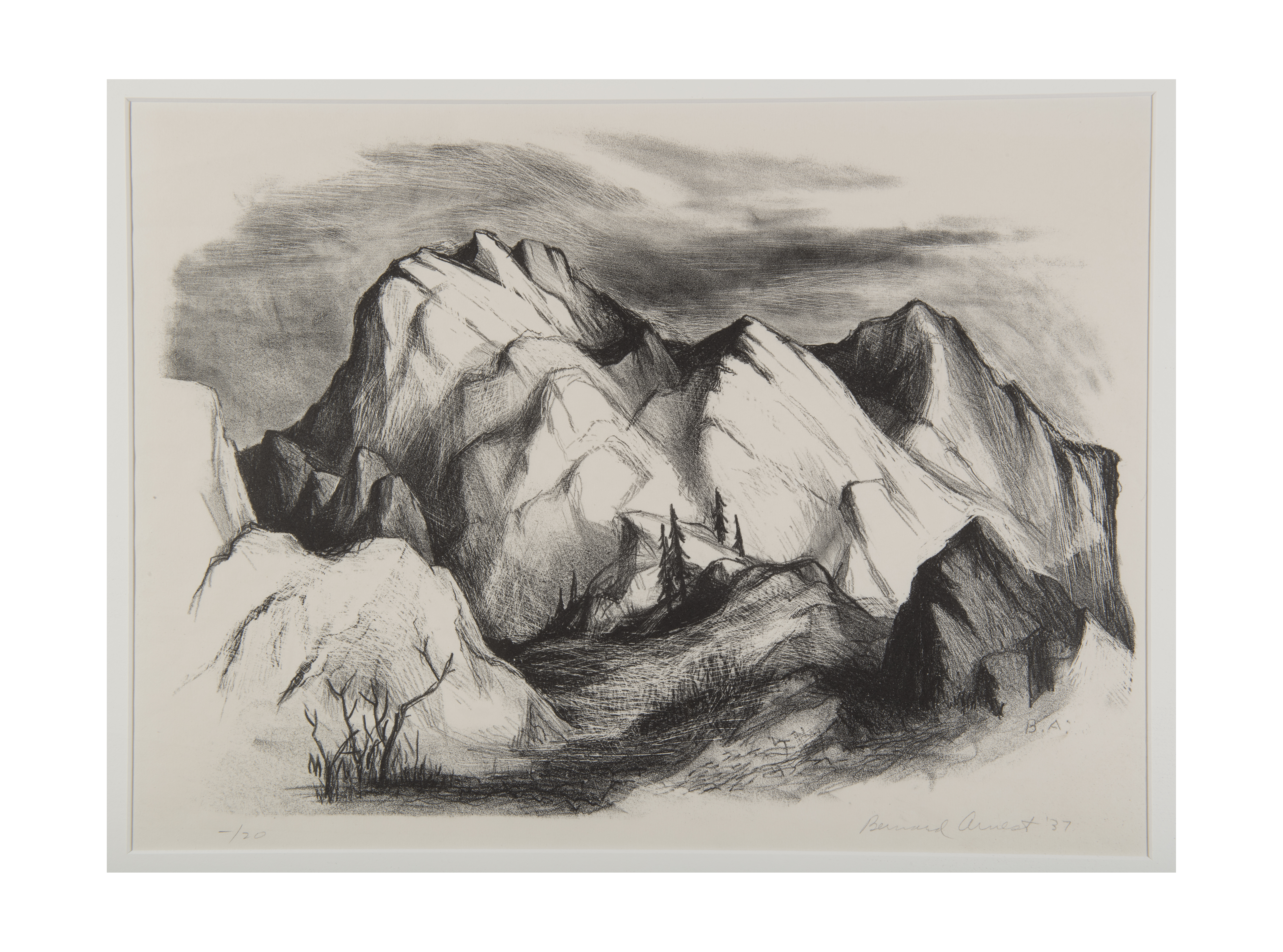

This idea resonated with some students at the Fine Arts Center, including Arnest, who studied lithography in the center’s summer session in 1936 with visiting instructor Charles Locke, known throughout the United States and Europe as one of the leading lithographers of his generation. Arnest produced several well-executed images, briefly working in the medium fourteen years later. In 1937 he created Garden of the Gods, which was printed by Lawrence Barrett, himself a former student of the Broadmoor Art Academy and a lithographer who, beginning in 1936, was an instructor in the medium. Barrett also managed the center’s lithography studio, printing limited editions of lithographs for established artists teaching there and for their students.

Robinson, who enjoyed an enviable record as a mural painter, became interested in the genre in the mid-1920s in New York and was the first to break with the mythological subjects of the Beaux-Arts school, traditionally considered the only ones suitable for public buildings. Prior to relocating to Colorado Springs, he had been commissioned by Edgar Kaufmann—owner of the Fallingwater House designed by Frank Lloyd Wright—to create a series of murals on The History of Commerce for the Kaufmann’s Department Store in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. (The Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center later acquired all of the canvases.)

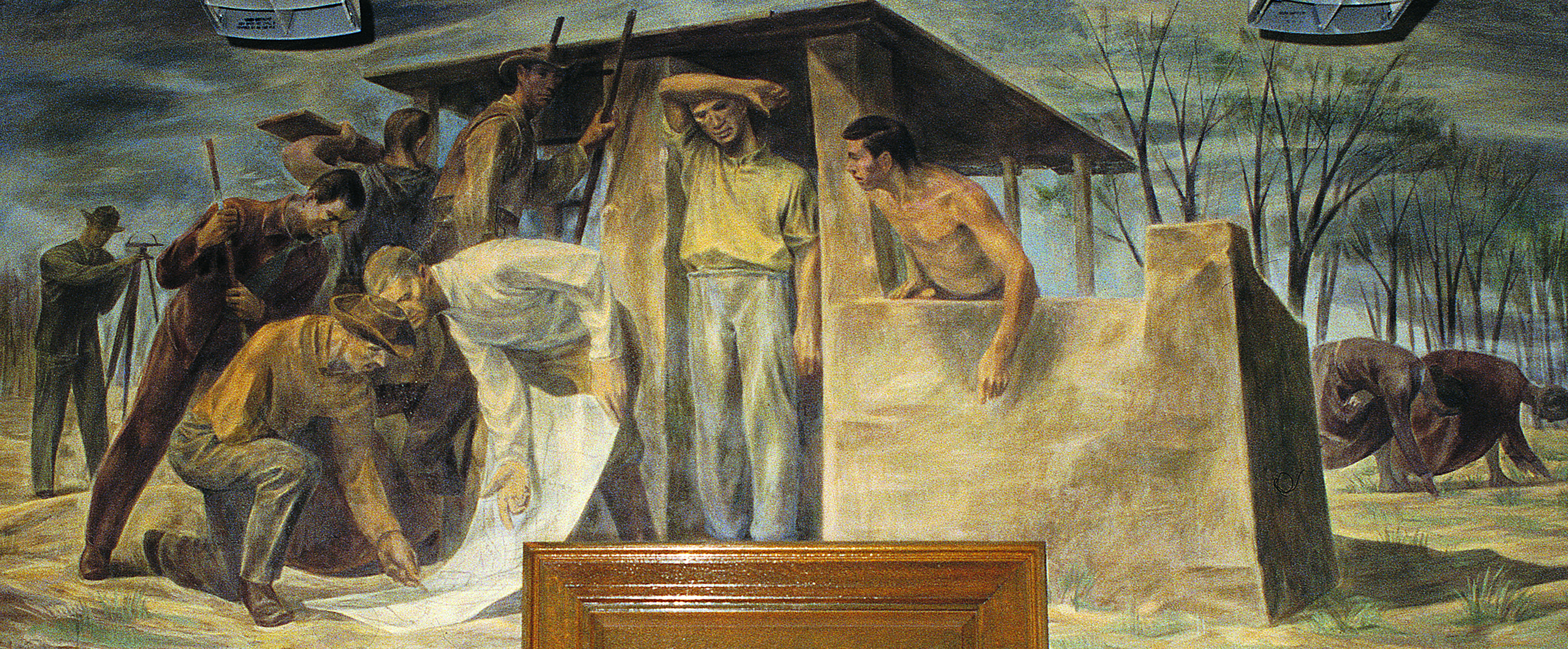

Arnest made this mural study in oil on illustration board as an exercise at the CSFAC art school around 1936 while a student of Boardman Robinson’s. Apparently, it never became a post office mural under the federal government’s Treasury Program.

Several of Arnest’s small-format paintings done as a Robinson student depict scenes of harvesting and cattle ranching , a part of western daily life. Reflecting his teacher’s preoccupation with draftsmanship, Arnest did not conceal the imagery with color and the entire composition depends not on patterns, but on the rhythmic curves and movement of the human figures and the animals.

The chosen subject matter—interpreting local scenes, vignettes from contemporary life, and historical events—characterized the contemporary realism or American Scene Painting from the 1930s and early 1940s. It distinguished the majority of murals produced for federal buildings, including post offices, under the Roosevelt administration’s Section of Painting and Sculpture (later called the Section of Fine Arts; the “Section”). It was one of the Depression-era government programs established to financially assist artists suffering from widespread economic dislocation at that time. Artists competing for mural commissions were selected from national and regional competitions to which they anonymously submitted maquettes, avoiding partiality in the judging process.

The Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, whose leading mural instructors were Robinson and Mechau, had an enviable success record in winning government mural competitions. From 1936 to 1940 forty murals by students and graduates of the center and twenty murals by current and former teachers were awarded in open competition and were executed.

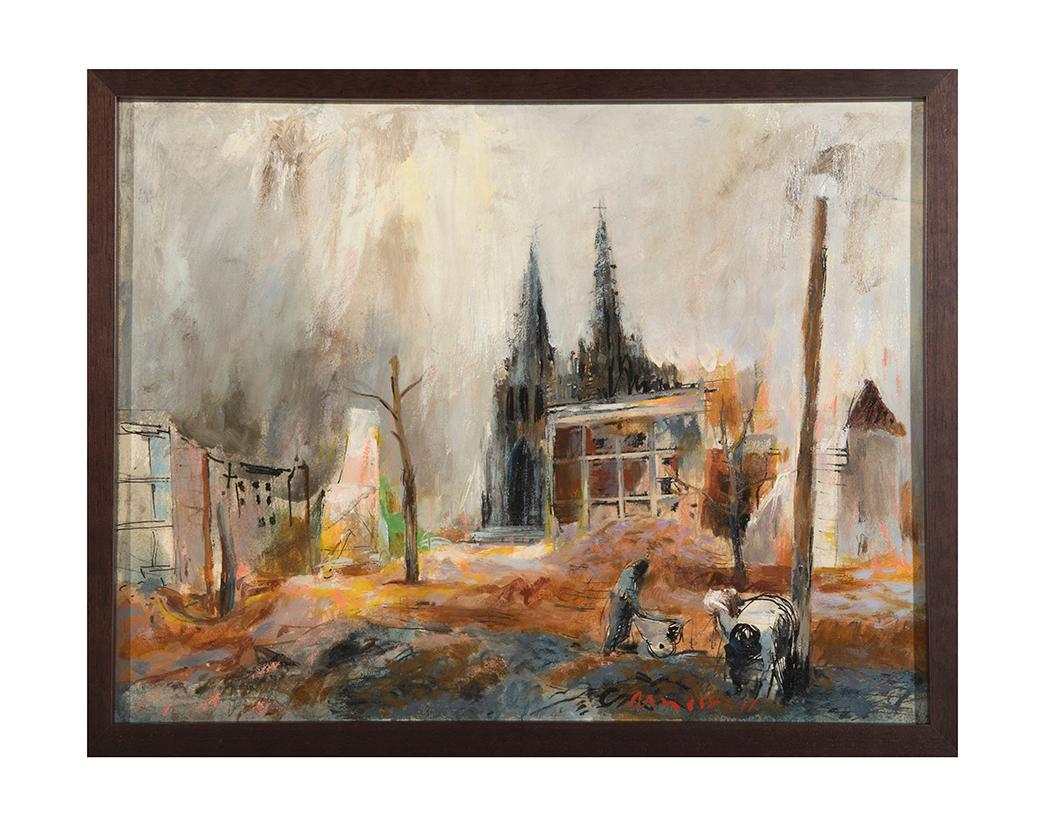

A 1940 oil on canvas, Arnest’s WPA-era mural was installed in the post office at Wellington, Texas, where it can still be seen. He painted it while in Colorado Springs in the late 1930s.

Arnest won the commission for the post office in Wellington, Texas , in 1939 and the following year installed the completed mural, where it remains in its original location. Titled Settlers on the Texas Plains and executed in a combination of tempera and oil on canvas, the mural shows a group of people building a shelter and sowing crops on the Texas plains, “fundamental activities,” in his words, “of opening and using a new land.”

He also submitted a mural design of a cattle drive in the Texas Panhandle to the Amarillo post office competition, but did not get the commission. In addition to his own mural painting, he and two other students assisted Robinson with his eighteen-panel mural for the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C., depicting portentous moments and leading figures in the history of law. After completing his studies, Arnest briefly served as Robinson’s teaching assistant.

Before graduating from the center he studied with Henry Varnum Poor, who had trained at the Slade School in London with Walter Sickert and at the Académie Julian in Paris with Jean-Paul Laurens. Poor imparted to Arnest his approach to painting, as described by New York art critic Howard Devree in the May 1940 issue of Parnassus:

Nature to Poor is the source of the beauty he seeks to convey. . . . His sparing use of details is frequently for emphasis on the fundamental form of the scene or an object, or to bring out some facet of character in a sitter and never a mere trick of adornment.

Poor’s view informed Arnest as an artist and a teacher of art after World War II.

While at the Fine Arts Center Arnest, Kenneth Evett, and half a dozen other students formed the “Off-Center Group” in 1936. They held semimonthly exhibitions of members’ work at 808 North Cascade Avenue in Colorado Springs open to the public on Sunday afternoons and Wednesday evenings. The exhibitions featured paintings, drawings and lithographs selected by Boardman Robinson and George Biddle, then a visiting instructor from New York.

In 1940 the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation—established in 1925 by Simon Guggenheim, a former US senator from Colorado, and his wife as a memorial to their son—awarded Arnest a fellowship in painting. He used it to do creative painting in San Francisco and to experience the city’s thriving art scene that included the San Francisco Museum of (Modern) Art, founded in 1935. The credits of its first director, Grace L. McCann Morley, include the Picasso retrospective in 1940, which Arnest visited. That same year the museum mounted Arnest’s one-man show, the first of a number in his professional career.

While in San Francisco he met Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Japanese American painter, printmaker, and photographer; a Guggenheim Fellowship awardee in 1935; and a visiting artist at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center in summer 1941. After viewing Arnest’s work, Kuniyoshi told him that he painted like an old man. As Arnest recalled in his “Statement from the Artist” in the catalog accompanying his Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center exhibition four decades later, Kuniyoshi’s unexpected but nonetheless forthright assessment initiated the younger artist’s understanding—later germinating in his Minnesota and Colorado work—that “a picture is also something after being a plane surface covered with colors and . . . that it contains implicit, even hidden, signs and messages that are its ultimate reality.”

Shortly before America’s entry into World War II after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the prewar military draft intervened and Arnest enlisted the previous month with the Army Signal Corps. Commissioned a Second Lieutenant a year later, he served for nine months in Iceland in 1943 and then with the Tenth Replacement Depot in England before joining a five-man team of artists in 1944 attached to the History Section of the US Army’s European Theater of Operations. It was established to collect information for use in the official American history of the war to be written and published after the end of hostilities.

Arnest served as the section’s Chief War Artist through the end of the war. While not specifically schooled for war art, he—like many of his fellow war artists—had been trained in representation, imaging, and picturing surrounded by the political and economic turmoil of the 1930s and the Great Depression, which conditioned them for recording the Western European wartime theater. Arnest worked in England, France, Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands, sketching and painting vignettes of American Army life, Buchenwald concentration camp prisoners, the meeting of Soviet and American troops at Strehla on the Elbe River in 1945, and the ruins of bombed-out towns and cities in which civilians tried to survive. He also received a Bronze Star for helping a rescue mission near a minefield in Aachen, Germany.

After the war he worked for two years in New York City, believing that every artist should spend at least one year there. During that time he began a thirty-nine-year affiliation with Kraushaar Galleries only ending with his death in 1986. In addition to acquainting himself with the new postwar developments in American art, he traveled up and down the East Coast painting scenes from North Carolina to New Hampshire.

Arnest’s "Eighth Street," late 1940s, oil on canvas. Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Julia B. Bigelow Fund, 49.8.

In 1947 as his money was running out he fortuitously received a job offer from the Minneapolis School of Fine Arts (since 1970, Minneapolis College of Art and Design—MCAD). He felt lucky to get a college teaching job with only a high school diploma and his certificate from the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. For a brief period in the late 1940s colleges inaugurated advanced art programs that included a lot of GIs studying on the GI Bill; too few MFAs existed to fully staff these programs so administrators enlisted instructors such as Arnest with other qualifications.

Shortly after Arnest assumed his new position as instructor of painting, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts gave him a one-man show of rural and urban landscape paintings and drawings of East Coast and wartime European subjects. A review in the institute’s Bulletin underscores the features distinguishing his forthcoming work in Minnesota and later in Colorado:

Neither aggressively modern nor stuffily traditional in style, they reveal a sensitive mind and an assured hand which have combined to produce a group of serene and beautifully integrated pictures. They make no sudden onslaught on the eye of the observer, having none of the bombast and none of the shrieking color by which much modern painting captures the attention. Their subtle color and unpretentious craft create a slower and more profound impression, thus making a claim upon the mind that does not loosen easily. . . . The misty quality of the air surrounding them transmits them onto a poetic plane and gives them a valor beyond that to be found in a bare translation of the elements of nature. . . . All of this adds up to pictures which have much to say and which say it in a manner that is no less forceful because it is restrained.

This version of Arnest’s "Signs" painting from 1950–51, an oil on canvas, is a good example of his referentially abstract style of the early 1950s. (The other version is at the Walker Center in Minneapolis.)

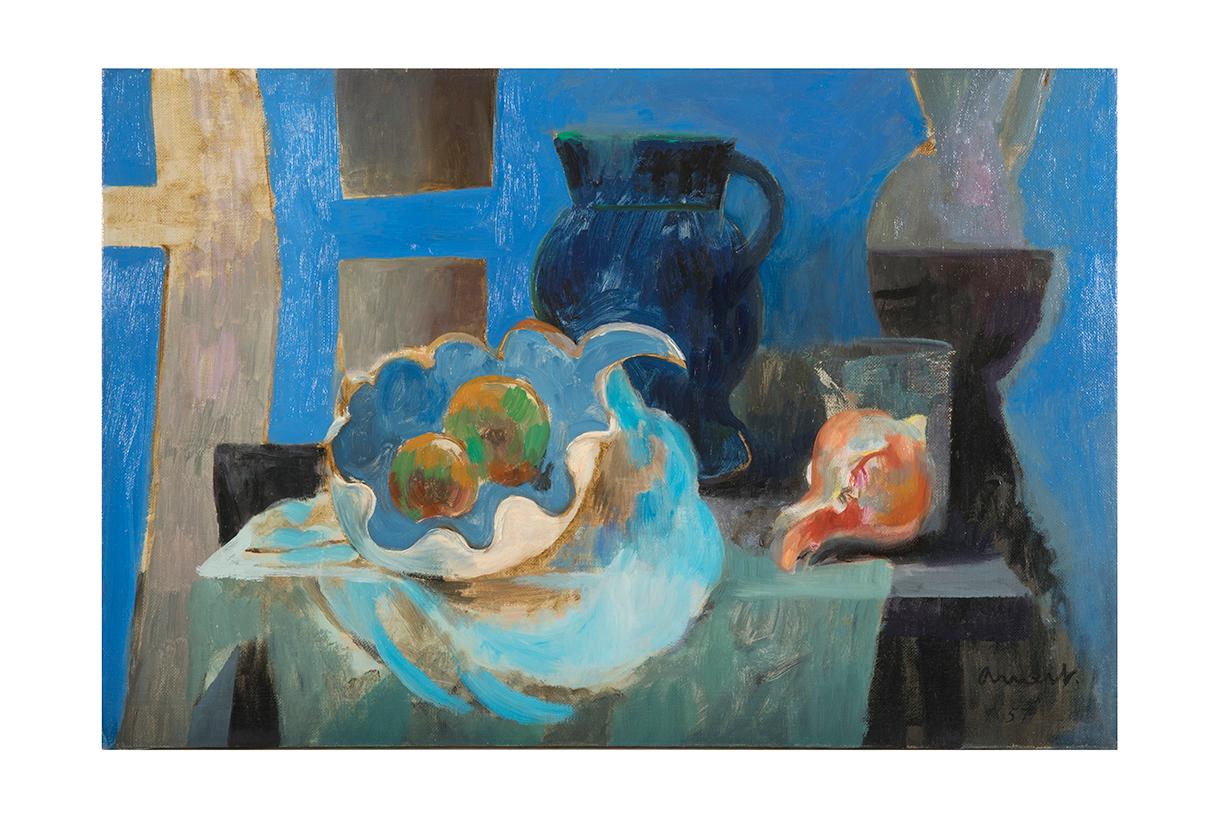

In Minneapolis he painted a number of referentially abstract cityscapes in which the buildings and other physical structures are geometrical form studies, as well as portraits and still lifes . He also produced large, self-contained abstracts along with several small-format suites whose varicolored abstract geometric shapes created depth and visual interest.

He enjoyed his excursion into abstract expressionism, the dominant art style at that time. He termed it “the most beautiful of all forms, when the painter was no longer obliged (or even interested) to picture, only to paint.” On account of his engagement with the fine arts at the University of Minnesota (instructor, 1949; assistant professor, 1950; and associate professor, 1955), he also was a lecturer in art at the Walker Art Center and the John Hay Fellows Program.

Reviewing Arnest’s solo show in 1954 at the Walker Art Center, John K. Silverman wrote in the Minneapolis Star:

Bernard Arnest is a poet in paint and there is a kind of magic in his pictures, where colors are flame and smoke. His reality is an improved reality, tinged with ecstasy. His lyric and mystic cityscapes transform and reorganize the humdrum elements about us and make them sing. . . . His color is free and aspiring yet subscribes to specific harmony in each painting. His play of forms, with their sharp and dulled edges and back-and-forth movement in depth, is endlessly fascinating.

Arnest’s service as an artist in the US Army earned him the commission in 1955 to paint a three-panel mural in the new Veterans Service Building on the grounds of the state capitol in Saint Paul, Minnesota. He based the composition on his wartime sketches and paintings with texts beneath the images excerpted from President Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. The following year the First National Bank engaged Arnest to paint an abstract mural for its bank branch (now closed) at the Southdale Center, the nation’s first indoor regional shopping mall, which opened in 1956 in Edina, Minnesota.

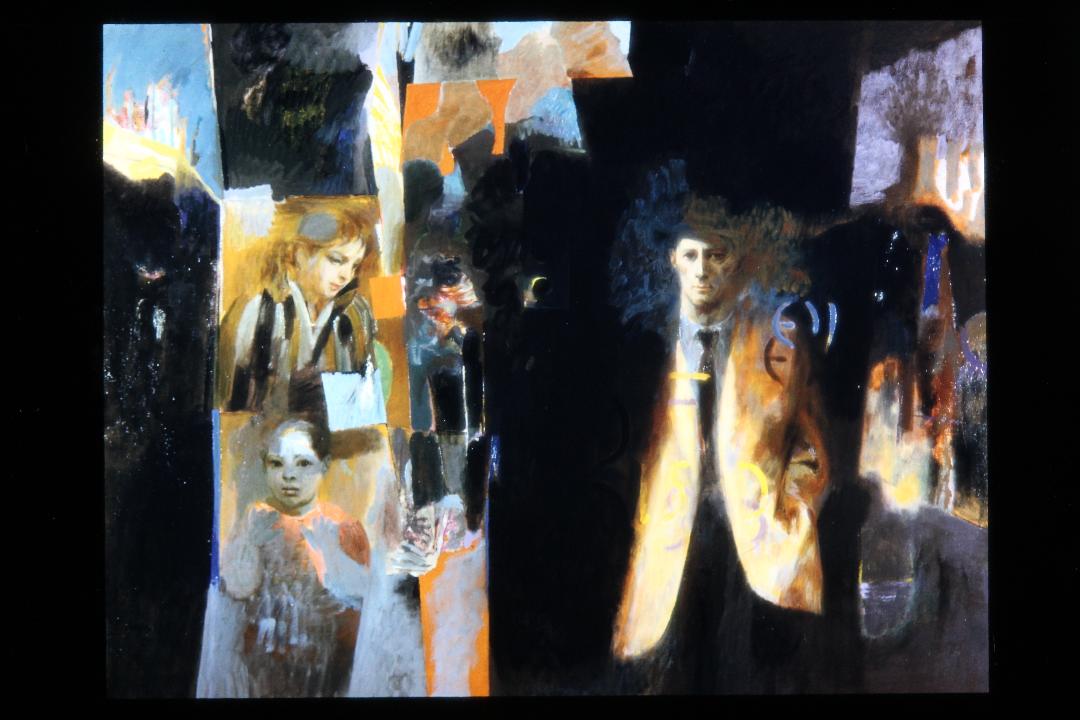

"Dark Reflection/Dark Window" was shown in the sixteenth annual Artists West of the Mississippi exhibition at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center in 1957.

In 1957 he submitted Dark Window (Dark Reflections) to the Sixteenth Artists West of the Mississippi exhibition at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. The large-format entry was part of his small genre on the subject from the 1950s, about which he wrote: “The ‘reflections’ and mirrored images attempt to picture the confusion of thought and the ambiguities of identity, the detachments and evasions that experience causes in us.”

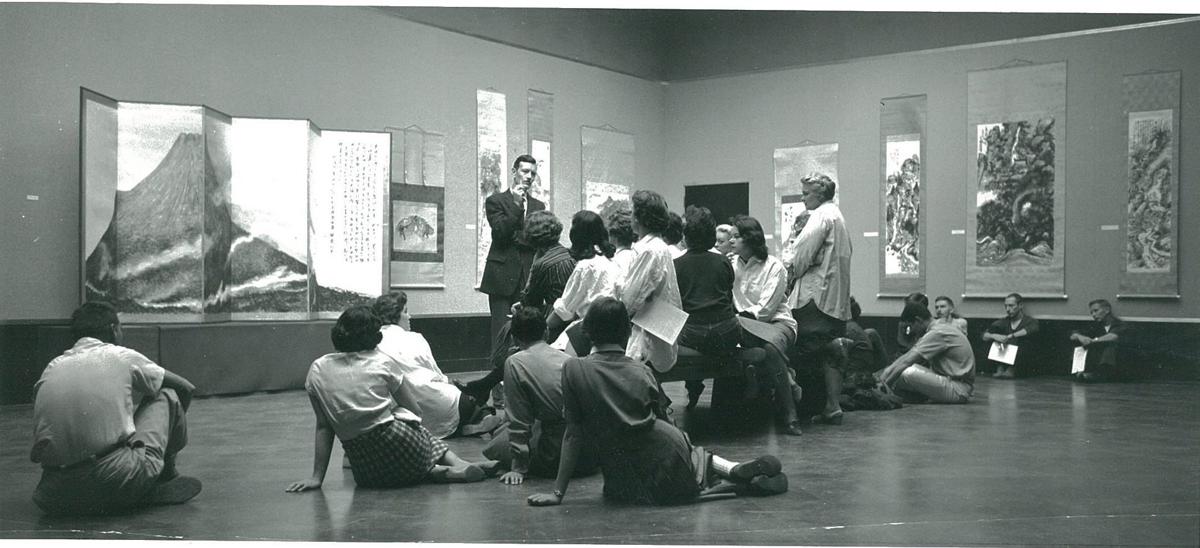

Boardman Robinson’s students at the school of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center assist him in the mid-1930s with his murals collectively titled "Great Events and Figures of the Law." The murals were installed at the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C. The student on the ladder is Bernard Arnest; standing is David Fredenthal. Photo by Laura Gilpin.

After completing the spring semester at the University of Minnesota in 1957, Bernard Arnest—over his wife’s objections—relocated their family to Colorado Springs. With three young children to support he found it hard to resist the attractive salary Colorado College offered him to join its faculty as professor and chairman of the art department after the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center had closed its fine arts school. As an art educator he likewise was a principal consultant for the Advanced Placement in Art program developed by the College Entrance Examination Board. In the early 1960s he also served as a consultant on college and university art programs at Stanford University, Pennsylvania State University, and the Ford Foundation.

These activities resulted in his serving in 1960 as a US Department of State consultant for its international educational/cultural exchange program and receiving a grant to depict the landscape and people of Afghanistan under the auspices of the US Embassy in Kabul. There, he lectured in English before select groups and also traveled around the country making field sketches. The paintings he did in the country formed his solo show that year at the American Exhibition at Kabul’s Afghan National Fair. Those works he brought back with him and the pieces he finished after returning to Colorado Springs later were exhibited at the Design Center and Art Galleries in Denver.

By the early 1960s abstract expressionism began to wane, prompting him to note:

The narrowing of mental life in the art world, the isolation of reference and the limiting of concern, has evidently played out and it may now be possible to recover things that have been lost without our noticing. Among these is something that can be thought of as fiction (not fantasy) with the empathies and sense of comprehension that is fiction, “the lie that helps us understand the truth,” has the power to give. Another is the recognition of the deep ambivalences we share. And always these things that cannot be named, but only imagined, painted.

A drawing from Arnest’s "Scenes from Life" series (1974–75) depicts his reaction to all that was happening in American society during the Nixon era.

In Colorado he painted subjects similar to those he previously created in Minnesota, chief among them landscapes, which he termed “appreciations and escapes from any metaphysical cargo.” He similarly continued with portraits and still lifes “made in the belief that there is a reciprocity between observation, as distinct from imitation and imagination.”

The war in Vietnam and the Watergate scandal in the late 1960s and early 1970s occasioned fifty-one drawings collectively titled Scenes from Life , shown at the Denver Art Museum in 1977 and now in the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center collection. A motif departing from Arnest’s typical tone and subject matter, Scenes represent his effort as an artist to distance himself from the era’s “silent majority” whose inaction condoned the incalculable harm being done to others at that time. Scenes, in his words, “critique the passivity and indifference of the fortunate and comfortable, the unthinkingly and conventionally cruel.” They recall Francisco Goya’s Los Caprichos series whose eighty prints constitute an enlightened, tour-de-force critique of eighteenth-century Spain and humanity in general. After the dark outpouring of Scenes from Life, Arnest revived himself with landscapes, economic and without intense detail but somewhat nostalgic.

One of Arnest’s favorite paintings, "Night Music" (oil on canvas, 1980) commemorates the old jazz days in Denver. It depicts the group Worthy Constituents at Josephina’s in the late 1970s. Visible are Mark Arnest, Bernard’s son (guitar), Michael Shea (piano), Michael Sweeney (flute), Rob Dando (bass), and Charles Ayash (drums).

"Rock Group with Drum," oil on canvas, about 1972. Arnest’s son Mark is the dark guitarist, David Booth the blond guitarist, Gregg Johnson the drummer, and Eldon Moore the nearly invisible bass player. The Arnest family’s Colorado Springs house at 1502 Wood Avenue had been Boardman Robinson’s home.

In the 1970s he painted scenes of musicians that he regarded as allegorical fictions of the ideal human community. He also made sketches of his son Mark’s high school rock ’n’ roll band , which practiced at full volume in the Arnest family living room, resulting in fifteen images with color and marvelous composition.

On the occasion of Arnest’s retrospective exhibition at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center in 1980–1981, its curator of fine arts, Charles Guerin, summed up the essence of his art:

Bernard Arnest has demonstrated throughout his long career a continuing ability to produce works of art which are unique. Unlike so many artists whose paintings are simply a logical progression of the work of other artists or an eclectic combination of current or past styles, Arnest’s pictures are highly personal and intuitive statements. They seem to possess a contained energy which emanates from the work and creates a sense of presence which is unmistakable. The works cannot be ignored. They captivate the viewer quietly as they demand consideration.

Arnest retired from Colorado College in 1982 as professor emeritus of art, a step he felt he should have taken some forty years earlier. While he enjoyed teaching , he welcomed the lack of schedules and deadlines, leaving him free to paint and do a little writing.

Although not very nostalgic, he could look back with satisfaction on a career as a distinguished teacher and as a participant with other leading American artists juried into important and prestigious national annual/biennial exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the National Academy of Design, both in New York; the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia; and the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh.

In 1984 the City of Colorado Springs awarded Arnest its Medal of Distinction for his outstanding contributions to the arts. On that occasion he shared with readers his uncomplicated creative formula in Scott Smith’s interview with him published in the Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph:

First, you have an idea—and where ideas come from nobody knows. I guess a lot of mine come from the environment. I make notes. And after the idea, then you have to have the desire to paint. To do that, the artist has to enjoy the instruments of his art—just like everyone else.

For Further Reading

The author thanks the artist’s son, Mark Arnest of Colorado Springs, for sharing his father’s archive, facilitating the preparation of this article. Mark and his sister, Lisa Arnest Mondori, kindly read the text and offered helpful comments. A good introduction to Bernard Arnest’s life and work, and the source of most of the artist’s own reflections in this essay, is the exhibition catalog Bernard Arnest, Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, December 5, 1980–January 25, 1981 (Williams Printing Company, 1980). His World War II art is discussed and reproduced in a large-format printout, Bernard Arnest: Art from World War II Europe, Commentary on the War Art Program, issued by Colorado College, Colorado Springs, in 1982 for the Art Program on War, Violence, and Human Values. The era of the Broadmoor Art Academy/Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, where Arnest studied, is discussed in Stanley L. Cuba and Elizabeth Cunningham, Pikes Peak Vision: The Broadmoor Art Academy, 1919–1945 (Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, 1989); and Stanley Cuba, John F. Carlson and the Artists of the Broadmoor Academy (David Cook Fine Art, 1999). Also of interest are Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center: A History and Selections from the Permanent Collections, published by the center in 1986; Archie Musick, Musick Medley: Intimate Memories of a Rocky Mountain Art Colony (Creative Press, 1971); and Robert L. Shalkop, A Show of Color: 100 Years of Painting in the Pike’s Peak Region, An Exhibition in Honor of the Centennial of Colorado Springs, 1871–1971 (Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, 1971).