Story

The Search for the Silver Queen

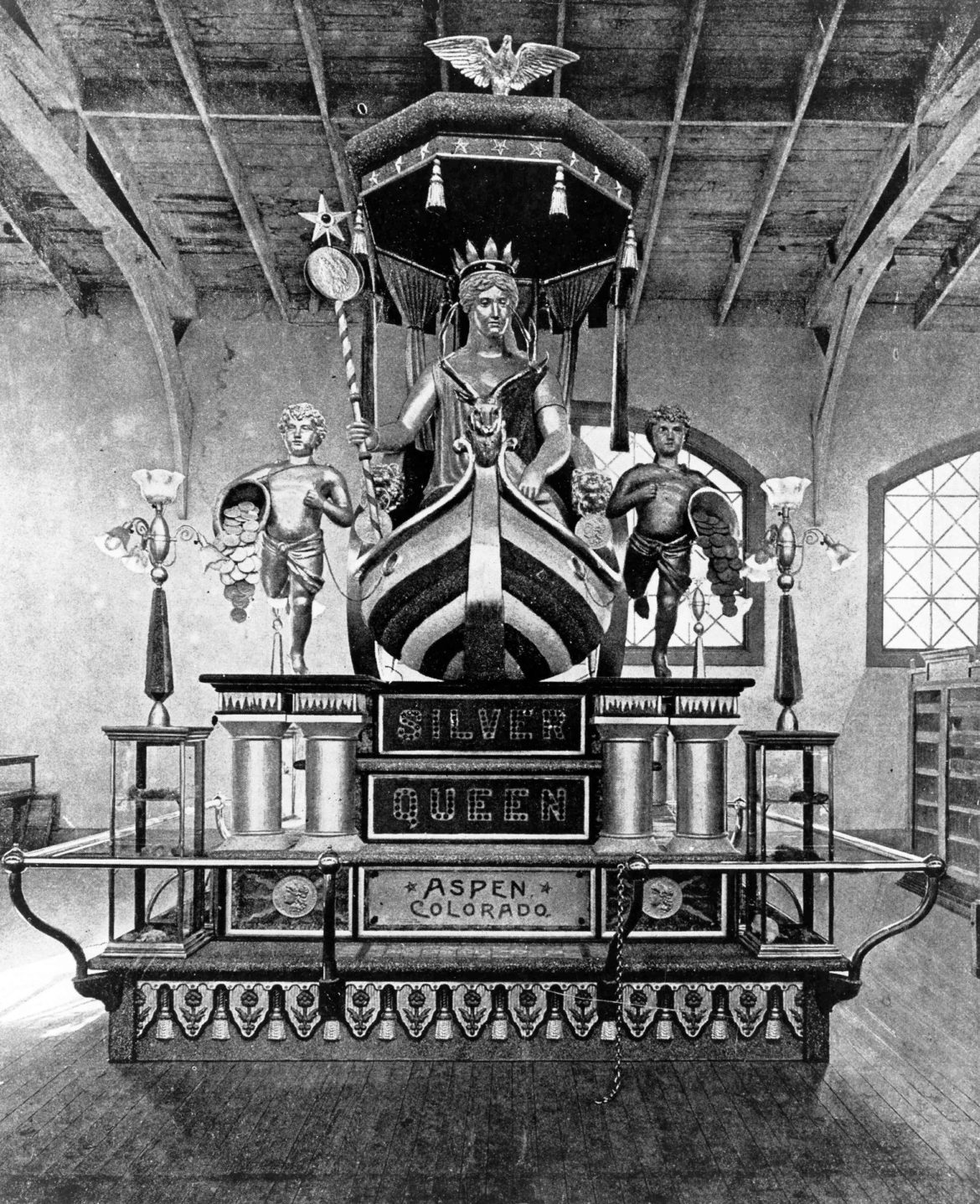

The Silver Queen of Aspen was once the crown jewel of the Colorado Mineral Palace in Pueblo. Along with her consort, King Coal of Trinidad, she reigned over a glittering kingdom of gems and precious metals, at the center of a vast display of our state’s mineral wealth.

But in 1939, the Mineral Palace closed its doors for the last time. And the Silver Queen was never seen by the public again. To this day, nobody knows exactly what happened to her.

The operators of the Mineral Palace commissioned local Pueblo artist Hiram Johnson to create two statues. King Coal was funded by Trinidad and was completed first, being installed in the Palace shortly after it opened.

The Silver Queen was much more expensive, and it took a few years to raise the necessary $7,000. She wasn’t completed until 1893, and was first displayed at Aspen before being brought to the Chicago World’s Fair. After the fair ended, she was permanently displayed at the Mineral Palace until its demolition, when she seemingly disappeared from history.

The Colorado Mineral Palace was a massive exhibition hall constructed in 1891 in Pueblo, but it had a long and troubled history. It was eventually condemned and torn down in 1942. The Mineral Palace Gardens park still bears its name.

The story of the Silver Queen has long fascinated many all across the state, especially in her hometown of Aspen where the question of her disappearance has become something of a local legend.

“Every city, county, state, or nation for that matter picks out certain items in its history and sort of focuses on those,” said Larry Fredrick, a long-time volunteer with the Aspen Historical Society. “The Silver Queen is part of the legend of Aspen.”

Fredrick has volunteered with the Aspen Historical Society for almost four decades. He describes himself as an “ad hoc historian,” spending much of his free time going through old records and documents to find the real history of his town. And for much of his time with the society, one of the most recurring questions in the community has been “Where is the Silver Queen?”

That question has been asked for a long time—basically since she first “vanished”.

In the 1950s, only a decade after the Mineral Palace was demolished, an Aspen daily newspaper was already demanding answers regarding the Silver Queen.

Even within a few years of the demolition, the story was already unclear. Nobody was certain whether she still existed or not, or where she had last been seen. Some newspapers even reported that she had been moved to city hall (which is almost certainly not true).

In the seventy years since, many different stories have arisen to explain her vanishing act.

The Silver Queen of Aspen was not made of solid silver, as some stories claim. Instead she was a polished surface over a copper or iron frame. However, some of the adornments of the statue- including the elk prow, the eagle, and the coins- were at least coated in precious metals.

One of the most popular legends is that the Silver Queen never returned from the World’s Fair in Chicago. Some say she was either stolen by corrupt fair officials, or that she was destroyed in a fire and there was some kind of cover up. These stories sometimes claim that the statue on display at the Mineral Palace was a plaster replica, and point to photos showing pieces of the Queen missing, or even the entire statue absent from the Palace.

This story is almost certainly untrue, and the proof is in those photographs themselves, according to Larry Fredrick’s detailed research.

The photographs depicting the Mineral Palace without the Silver Queen are easy to explain—they all date from between 1891 and 1894. The Silver Queen was only displayed at the Mineral Palace after the World’s Fair, and during the years leading up to that she, of course, was absent.

As for the photos in which she is missing pieces—specifically the coins flanking her, and the elk head at the prow of her chariot—those images all date from after 1935. That year the city of Pueblo closed the Mineral Palace for repairs and refurbishment, including to the statues inside. Photos showing the Silver Queen from between 1894 and 1935 show her to be complete and whole until these repairs took place.

Others hold out hope that the Silver Queen might still exist somewhere, hidden in some basement or lost in storage. But that is unlikely as well.

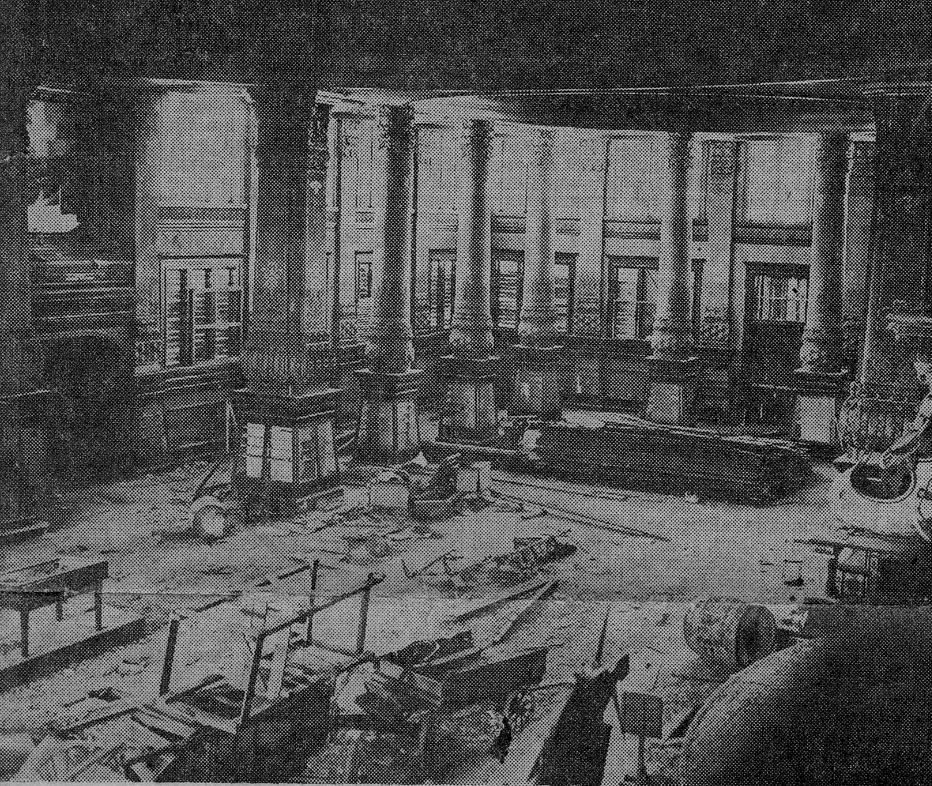

The last known photo of the Silver Queen is also possibly the last photograph of the interior of the Mineral Palace, dated October 6, 1942. City officials had condemned the building by this point, noting the danger it posed to the public. And in the lower right corner of the photograph sits the Silver Queen on her chariot.

This photo of the Palace interior dates to October 1942, either at the beginning of the demolition or just before it began. The remains of the Silver Queen can be seen on the right edge of the frame.

She is heavily damaged, with holes visible in her silver “skin.” According to newspaper articles dating from not long after the palace’s destruction, vandals who broke into the building during its closure gravely damaged the King and Queen of the Mineral Palace. During the process of salvaging the mineral exhibits for relocation, the Palace’s curator reportedly declared the statues to be unsalvageable and ordered them destroyed.

And so it seems almost certain that the Silver Queen was destroyed with the Mineral Palace, and that nothing remains of her. But the seventy-year search is not quite over. A newspaper article is almost damning, but isn’t one hundred percent conclusive.

Until official records are found showing that the Silver Queen was ordered to be disposed of, the search will no doubt continue. Perhaps someday soon, some long forgotten scrap of evidence will be uncovered, and the city of Aspen will finally know for sure, one way or the other, what became of their famous Silver Queen.