Story

“Nobody Should Go Unremembered”

Locating the 1921 Pueblo Flood Mass Grave at Roselawn Cemetery

Near and dear to the people of Pueblo is Roselawn Cemetery—a place of family and community connections that holds so many memories of Pueblo’s past. The State Historical Fund recently supported a project to find the exact location of the mass burial that followed the catastrophic Pueblo Flood, prompting reflections on the meaning of tragedy, closure, and remembrance.

Roselawn Cemetery Executive Director Rudy Krasovec and Roselawn Cemetery Association Chair Lucille Corsentino.

“My family is all buried here, my grandparents on both sides of the family, my dad,” says Rudy Krasovec about Pueblo’s Roselawn Cemetery. Growing up, he visited loved ones at the cemetery and cared for the grounds with his family.

“All my family is buried here,” says Lucille Corsentino. “I will be eighty years old in August,” she adds, “and I can remember coming to Roselawn. It was like a weekly ritual with my family. I’d come out with my dad and we’d mow the lawn and we’d trim, plant flowers. I lost my husband twenty-two years ago and he is buried here, so Roselawn is the place where my heart is. I just feel very connected to it.”

In their current roles as chair and executive director of the Roselawn Cemetery Association, both Lucille and Rudy continue to care for the cemetery today.

As the association’s chair, Lucille and other contributors wrote the book The Hearts and Souls of Roselawn in 2018. “It is a collection of stories of people who have their loved ones buried at Roselawn,” she says. “Many of the stories are about the 1921 flood. It sparked a lot of interest.”

Hundreds died in the 1921 Pueblo Flood, one of the deadliest natural disasters in the state’s history. Many, but not all, were identified. Where are those unidentified victims buried? Oral history relates that the unidentified victims went into a mass grave at Roselawn.

“We first learned of the mass graves years ago from our executive director, Kevin McCarthy,” Lucille recounts. “He passed away in 2019. He had always shared a story about his great grandfather T.G. McCarthy. He was the coroner at the time of the 1921 flood. The story goes like this: They had 2 to 300 bodies that they couldn’t identify. They didn’t know what to do with them so they took them to Roselawn and they dug a mass grave. Well, Kevin and I...narrowed it down to blocks 27, 26, and 25 in our Historical Area, which was originally the pauper’s area of the cemetery, where they put the people who they thought were the least of their brothers.”

Today, the Historical Section of the cemetery is an area with minimal landscaping and few headstones.

In 2019 Lucille reached out to the History Colorado State Historical Fund about grant opportunities to locate the potential mass grave. The Roselawn Cemetery Association applied for and was awarded a grant to utilize non-invasive geophysical survey techniques. Team members from Alpine Archaeology and the Colorado School of Mines’ Center for Gravity, Electrical, and Magnetic Studies looked for evidence of the mass graves from the 1921 Pueblo Flood, the 1904 Eden train wreck (a disaster north of Pueblo that claimed roughly 100 lives), and the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic.

Principal investigator Michelle Slaughter of Alpine Archaeological Consultants, and Sigourney Burch and Hannah Haugen of Colorado School of Mines

Alpine Archaeologist Michelle Slaughter thought determining the resting place of the unidentified victims could easily be determined from funeral home records. Three funeral homes existed in 1921, but she found that none of their records remain: one of the homes was destroyed in the flood, another’s records were destroyed in a fire, and the last didn’t retain files after a 1960 change in ownership.

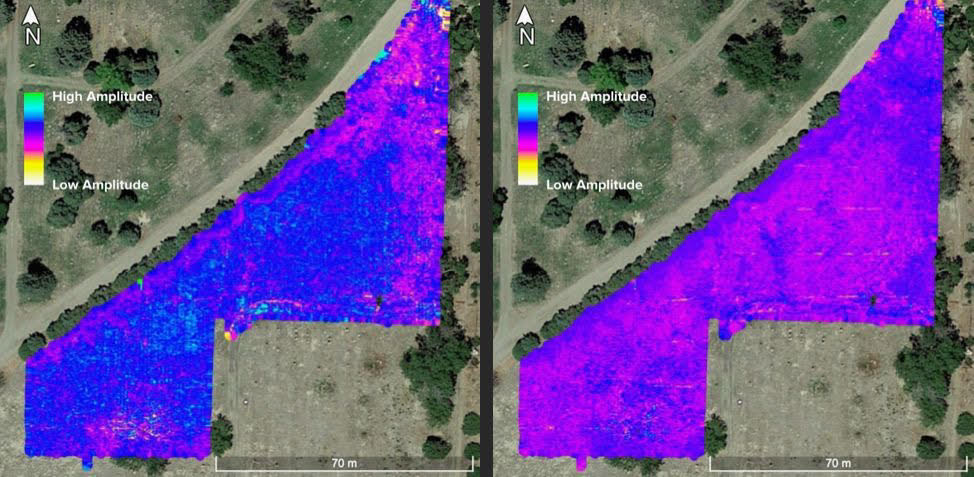

The Colorado School of Mines students launched the project in 2020 only to be stalled by the Covid-19 pandemic. Those students graduated before the research could be completed. Senior Sigourney Burch took up the project in 2021, conducting a ground-penetrating radar survey of large swaths of Historical Sections 25 and 27. Ground-penetrating radar is a non-intrusive method of mapping the sub-surface using radar reflections. The data collected was challenging to interpret, as the headstones didn’t align with reflections that indicated burials. She and her professor, Dr. Richard Krahenbuhl, realized that what they presumed to be background noise in the data was actually evidence of human remains—a lot of individuals.

Ground-penetrating radar data overlaid on aerial image of Roselawn Cemetery. Data is collected linearly. Lines of data are computer processed and sliced horizontally to create these “slice map” images. The images are like cake layers, showing common reflections for large areas at different depths.

The team knew that the free cemetery area was heavily utilized, but the extent of use surprised them. Roselawn records indicate that up to fifteen individuals were buried in a 15-by-15-foot block. Michelle Slaughter explains that “the area they were looking at is the pauper’s section…. Even though the graves are not marked, there are a couple thousand people crammed in a small area.”

“It was very interesting to not only learn about everything that Pueblo went through in the early 1900s,” Sigourney Burch adds, “but also [to] truly understand the loss of life associated with these events, how impactful these great tragedies were. When you are standing in that field and recognizing how many folks are buried out there.” That density of people has led the team to believe that most, if not all, of the people in these free sections were buried in shrouds, not coffins.

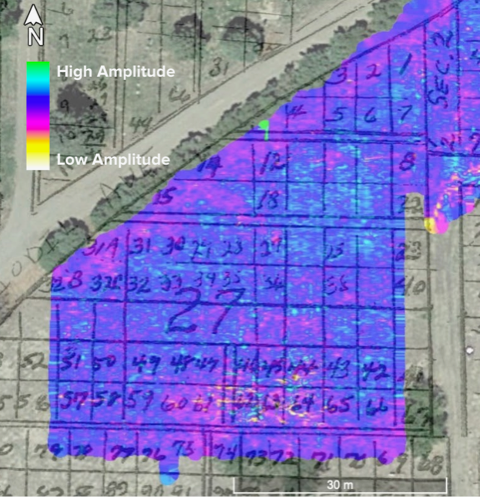

The 1913 map of Roselawn Cemetery is overlaid with the ground-penetrating radar data and an aerial map. The row without any lot numbers was labeled “Beech Lane” on the 1910 map. The radar data shows no discernable change between Beech Lane and the numbered lots, indicating that people are buried throughout the lane. There are no known burial records for Beech Lane. Researchers hypothesize that this is the location of mass graves at Roselawn Cemetery.

Armed with these new findings of dense burials, the team compared the data with historic cemetery maps. They noticed that in 1910, Section 27 was bisected from east to west by Beech Lane. Today, no evidence of that road remains. Although there are no recorded burials in the mapped Beech Lane area, the ground-penetrating radar data indicate a high density of burials. The team’s working hypothesis is that the former road is the location of mass burials for the three Pueblo tragedies.

As Sigourney Burch explains, “The fact that we have a section that looks exactly the same as where those dense burial areas are happening, but it doesn’t have any historical records associated with it, led us to the conclusion that this is probably our area of future work. More historical research needs to be done to really determine if this is the site of a mass grave.”

Roselawn’s Historical Section is the original “pauper’s area” of the cemetery, and today has few tombstones and minimal landscaping.

This research also highlights Pueblo’s diverse community. The Roselawn Cemetery was founded as Riverside Cemetery in 1891, and the name was changed to Roselawn in 1905. It was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2017 for its association with the development of Pueblo, for its representation of Pueblo’s culturally rich community, for the craftsmanship of the headstones, and as a sample of the early twentieth century’s “lawn-park” cemetery movement. Archaeologist Michelle Slaughter states that “Pueblo has and had such a diverse population from so many different places. When you look at the known burials in known graves you’ve got all of these other ethnicities and I think it is sobering knowing that if that mass grave is out there that probably the majority of the people in it are from ethnic groups that are not white. Probably a lot of immigrant folks that they couldn’t identify because they were here alone or immigrant families without bigger community ties.”

She adds, “I think it is very poignant thinking that there are all these people lost, and they have been lost to time in some respect due to their ethnicity and their socio-economic status.”

School of Mines student Sigourney Burch relates that she “grew up in Colorado, but a lot of this stuff doesn’t get talked about very often. It wasn’t in any of my high school classes.”

Colorado School of Mines students conduct the ground-penetrating radar survey at Roselawn’s Historical Section.

These stories are important to tell. As Roselawn Cemetery Association chair Lucille Corsentino puts it, “Nobody should go unremembered. Everybody deserves to be remembered.” In May, the association received a second History Colorado State Historical Fund grant to remember the unnamed lost in the flood. The grant is funding the production and installation of fifteen storyboard signs throughout the cemetery. One will tell the story of each of the three Pueblo tragedies and their corresponding mass grave sites at Roselawn.

With the hundredth anniversary of the 1921 Pueblo Flood in June 2021, it is fitting to be doing this work now. Michelle Slaughter reflects that this “is such an important project to try and help provide not closure, but at least try and provide some additional information for something that has been so open-ended and tragic for so long.”

Roselawn Cemetery Executive Director Rudy Krasovec and Roselawn Cemetery Association Chair Lucille Corsentino point out the location of Beech Lane, the area of the mass burial.

Project Collaborators and Credits:

Roselawn Cemetery Executive Director Rudy Krasovec

Roselawn Cemetery Association Chair Lucille Corsentino

Alpine Archaeological Consultants Principal Investigator Michelle Slaughter

Colorado School of Mines (CSM) Center for Gravity, Electrical and Magnetic Studies

CSM senior Sigourney Burch, with support from Professor Richard Krahenbuhl

CSM seniors Hannah Haugen, Paul Bonn, Arsya Kadyanto, Dylan Mayes, and Emily Moren

CSM master’s student Tannor Ziehm,

CSM Geophysical Department equipment manager Brian Passerella

ISC Geoscience Principal Geophysicist Ryan North

Rocky Mountain Tree Ring Research Dendrochronologist Dr. Peter Brown

Archaeologist and culturally modified tree specialist Marilyn Martorano