Story

A Moment in Time

We asked Coloradans one question: If you could have been an eyewitness at a historic event, which one would you choose?

There are moments in your life that you might be able to recall with precision. The first, thundering cry from a newborn. What it felt like to say goodbye to a grandparent. The squeeze of a friend’s hand after a long day at work. The warmth of the summer sun on your face; the chill of winter’s wind.

The past two years have left plenty of indelible marks on our collective memories. But instead of focusing solely on the contemporary, it made us ponder—as we often do—the past. If we could cast back in time, what historic moments would we have liked to witness? There are plenty to choose from: listening to the first Red Rocks Amphitheatre concert, marching with Corky Gonzales, and attending the first Juneteenth celebration, to name a few. But that’s just the start. To broaden our search, we asked Coloradans to send us their responses, which inspired, educated, and encouraged us to learn more. Come, take a step back in time with us.

The Moment: Governor Ralph Carr’s time in office

A moment in history I would have liked to witness was 1942. This was a horrible time for our country and for our state. I do not wish to witness all of the awful things that were done to the Japanese and Japanese Americans in our state and in our nation, but I would have liked to witness the character and principle of Governor Ralph Carr. He was a man who stood up for the rights of the American citizens of Japanese descent when no one else would. As someone whose grandfather, great-uncle, and great-aunts were incarcerated during this time, this period in our history resonates greatly with me. My grandfather was incarcerated at Tule Lake (California) but my great-uncle and aunt were incarcerated at Amache (Colorado’s incarceration camp for Japanese and Japanese Americans). Because of the work that Ralph Carr did, they were able to leave Amache and go to the University of Denver to finish their schooling. They have been forever grateful to the man who stood up for their rights when no one else did. I wish I could have seen this honorable man in person and thanked him from the bottom of my heart for standing up against injustice and fighting for the rights of all American citizens. —Sara Moore, Executive Director, Colorado Dragon Boat Festival

Three Japanese American women at the Granada Relocation Center in Amache on December 13, 1942.

The Moment: The 1980 State Spelling Bee

This one’s a bit niche, but as a former two-time Colorado State Spelling Bee champion, I would’ve loved to see Jacques Bailly win the state spelling bee in 1980. He won the national bee that same year and has since become the Scripps National Spelling Bee’s official pronouncer and an unparalleled icon in the spelling world—most importantly, an unparalleled Colorado icon. Lots of people don’t know that the person pronouncing the words on national TV every year grew up in Colorado, but he did! He was possibly the biggest celebrity of all to me as a kid, and I’d personally consider him as much an icon of Colorado history as anyone. —Simon Lamontagne, former Colorado Spelling Bee Champion and student at Dartmouth College (class of 2024)

The Moment: The creation of the root beer float

Mining towns of the mid- to late-1800s housed both substantial hardship that came with being in the working class, and increased avenues of luxuries and entertainment that grew much more accessible than they once were for the average American. One such phenomenon was the creation of the “Root Beer Float,” which was inspired by the snow-capped peaks of Cow Mountain. Frank J. Wisner, who owned the Cripple Creek Cow Mountain Gold Mining Company and Brewery, gazed upon the snowy mountain peaks one cool August evening in 1893. He saw the light of the full moon over them, faintly resembling what he thought was a perfect scoop of vanilla ice cream floating atop a glass of dark soda (Myers Avenue Red Root Beer, to be exact). He named his creation the “Black Cow.”

This event is one that resonates with me because it engenders a feeling of liberation among the working class. It informed an evident casualness to their pleasures and created a carefree and fun loving sentiment that has carried into today’s Cripple Creek, now a prominent tourist and outdoor recreation destination. Oh, and the event furthermore resonates with me because, well, I quite like root beer floats. —Vishal Balaji, Program Facilitator and Oral History Indexing Volunteer

The Moment: Formation of Glenwood Canyon

I would love to travel back three million years ago to see the Colorado River just begin to carve Glenwood Canyon, nearly half a mile above the river’s location today. After two consecutive years where we have witnessed—and Colorado Department of Transportation crews have responded to—devastating natural disasters, the chance to see the canyon in its infancy would be a powerful reminder of the change Mother Nature is capable of making to our landscape.

In dozens of visits to Glenwood Canyon, I’ve gotten to learn more about the stunning geology that is right before our eyes as we pass through. The Colorado River has exposed rock formations as old as 1.7 billion years, and in the rockfalls that hit I-70, we see various rock types that span this immense time frame.

While I-70 through Glenwood Canyon is a challenging stretch of road that faces growing threats from climate change, it offers us an unequaled look back into our ancient past that never ceases to be breathtaking. The next time you’re a passenger traveling through, I hope you admire that beauty and history. —Shoshana Lew, Executive Director of the Colorado Department of Transportation

The Moment: When the Ute people discovered hot springs in Glenwood Canyon

As a science nerd, there are many times I would like to travel back to. However, if I could only travel back in time to one place I would love to be present when the Ute people first discovered the natural hot springs in what is now Glenwood Springs. I cannot imagine how bizarre it must have been. Traveling through the beautiful, awe-inspiring Glenwood Canyon and finding spots of very hot water. Some areas are over 100 degrees Fahrenheit. From the first discovery, to the first soak, to the first sweat in the vapor caves. How amazing that must have been. —Autumn Rivera, Colorado’s 2022 Teacher of the Year; sixth grade science teacher at Glenwood Springs Middle School

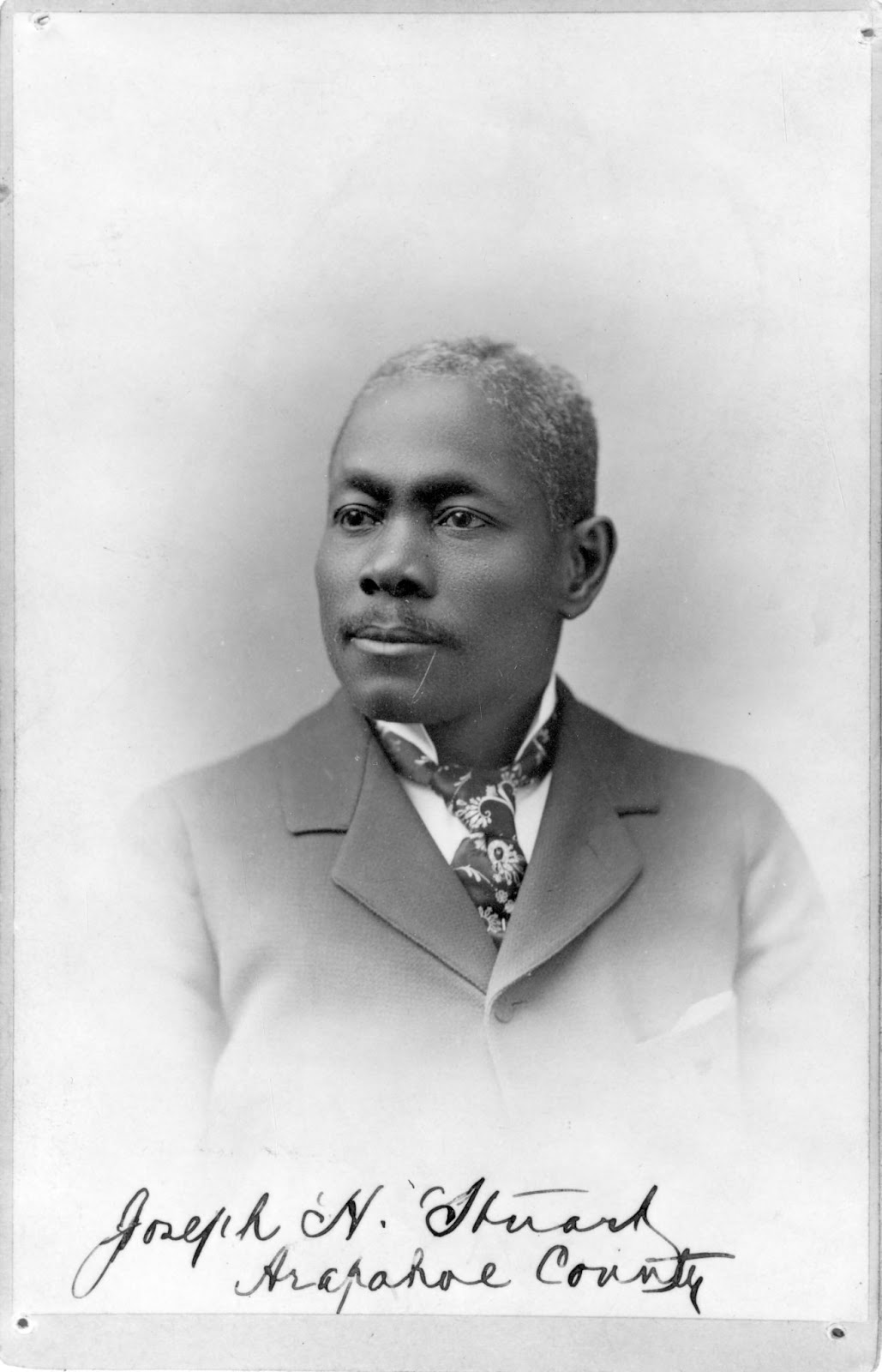

The Moments: Civil rights milestones and a barbecue riot

Once my time machine functions properly, there are three moments in Colorado history that I’d love to have witnessed. The first moment is an extended one. From 1865 to 1867, a group of African American men launched a sustained, and ultimately successful, civil rights campaign to include their right to vote in the state’s constitution. The second moment is April 1895 when Colorado State Representative Joseph Stuart, an African American, successfully sponsored a civil rights bill that had the same legal framework as the federal Civil Rights Act passed in 1964. Stuart’s bill passed and was enacted with no opposition. Third, was the spectacle I call “The Great Barbecue Riot of 1898.” Columbus B. Hill, an African American and prominent barbecue cook, oversaw a VIP barbecue dinner to help persuade key influencers to keep the Stock Show in Denver. The original guest list included a few thousand people and a menu that promised to barbecue almost every animal imaginable. However, more than twenty-five thousand people showed up for free barbecue. As you can guess, it didn’t end well. The crowd pressed to get some food and a riot ensued. The farce garnered national headlines, and Hill’s reputation took a temporary hit. It would have been quite the sight to behold and a feast to savor. —Adrian Miller, food writer, James Beard Award winner, and certified barbecue judge

The Moment: The creation of the Colorado State Highway Courtesy Patrol

As I reflect on the long history of the Colorado State Patrol, I would have liked to have been around in the spring and summer of 1935 to see my agency created. In April, the legislature passed a bill creating the Colorado State Highway Courtesy Patrol. This was at a time when horse-drawn wagons were as common as an automobile, and roads were often just dirt trails. This was still twenty-one years before funding for the Interstate Highway System was approved.

On September 23, 1935, out of 7,500 applications, forty-four men reported to Camp George West to begin their training. They lived in tents for twenty-eight days before graduating on October 20, 1935. Nowadays, cadets receive twenty-eight weeks of training. Armed with only a .38 caliber revolver, these patrol men set out patrolling our roadways. Seventeen of them were on Indian motorcycles. Having been a motor officer for several years, riding on a modern motorcycle on today’s roads, I struggle to imagine them trying to start those temperamental machines, riding them on the vast number of unimproved roads year-round, with only a leather coat and cloth hat to keep them warm. The patrol men who developed the foundation our agency would be built upon were truly made of different material and I wonder how I would have measured up to their grit and determination. —Lieutenant Colonel Barry Bratt, Colorado State Patrol

The Moment: Labor movements of the early 1900s

The fight for workers’ rights has been an extensive and important part of United States history. In my junior year AP US History class, I wrote a research paper analyzing the effects of the Haymarket Massacre of 1886—a peaceful labor rights protest in Chicago that turned into a deadly shootout after an unknown source threw a bomb. The event was followed by a series of legal proceedings that sentenced prominent figures who supported the protest to death. Years following, there were continued setbacks in labor movements around the country as strikes were crushed, unfair trials proceeded, and there was a lack of a change in legislation to provide fair working environments. In our own state of Colorado, there was a long enduring battle for workers’ rights that often remains untold. In 1914, the Colorado coal strike climaxed in an event known as the Ludlow Massacre in which at least nineteen people were killed.

I would want to see the nationwide response to this event and how it still took decades to achieve justice—as it wasn’t until 1938 that payment in scrip wages and child labor became illegal under the Fair Labor Standards Act. —Arman Kian, high school senior at the Kent Denver School

The Moment: The Civil Rights era

The moment in history I would most like to witness is the Civil Rights era. I am a student and a beneficiary of these trailblazers, who, going as far back as the Tuskegee Airmen, broke barriers, marched, or even refused to give up their seat on a bus so that everyone who came after them, and not just those at the time, would have greater equality and new opportunities. Every experience I have, personally and professionally, as an African American in Denver and Colorado is informed by the courage and sacrifices of those who stood up and demanded change. And when you look at what we are still determined to achieve today, whether it’s equity, greater social justice or securing voting rights, we must continue to champion these causes because these heroes passed the baton to us. We have a responsibility to history and to future generations to pick up that baton and carry it forward. —Denver Mayor Michael Hancock

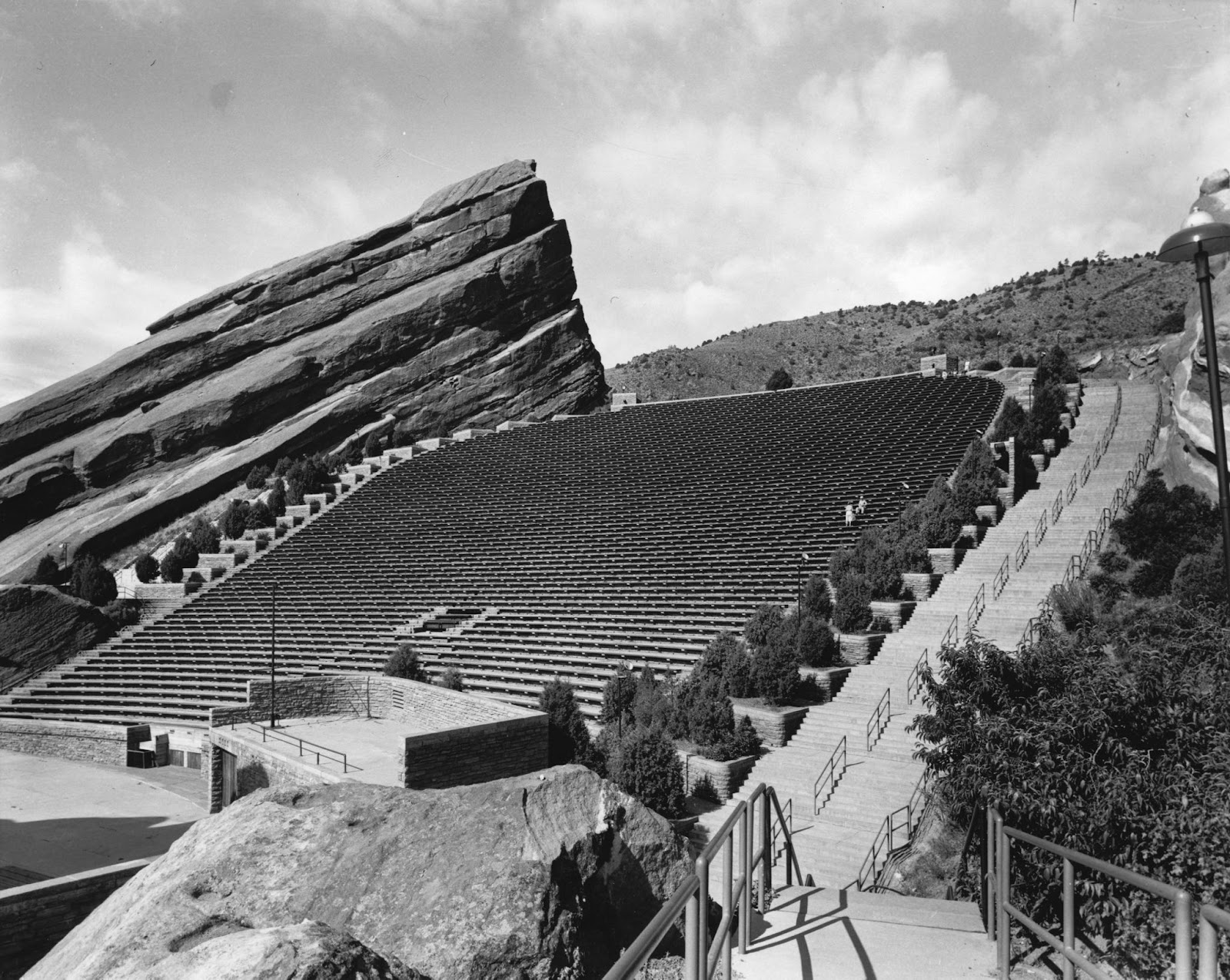

The Moment: The Beatles at Red Rocks Amphitheatre

Imagine, standing within row after row of stone, stretching on tiptoes to catch a glimpse as the screams of 7,000 fans collide. The lights go out. Suddenly the first bars of “Twist and Shout” burst forth, turning the roar into a fever-pitch. Even in my dreams, watching The Beatles play at Red Rocks Amphitheatre (1964) is spectacular, but oh, to have lived it.

During this time, the Vietnam War escalated abroad, violence continued with race riots across our nation, and only a month prior, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law. With civil unrest still plaguing our country, I would have been honored to witness Coloradans come together to celebrate the joy, music, and message of The Beatles in the most beautiful and acoustically pleasing outdoor concert venue in the world (I’m only a little biased). It not only represented a microcosm of pop culture in 1964, it secured the status of a beloved Colorado venue. It also foreshadowed the vibrant arts and culture scene in the Denver metro area, of which I am so proud. Was it profoundly important? Perhaps. Was it endlessly cool and indicative of the rock-on Colorado spirit we still exude today? Absolutely. —Katherine Rose Rainbolt, Chief Marketing Officer, Tattered Cover Book Store