Story

What does Equal Suffrage mean?

Who was included and excluded in the 19th Amendment

For the last year, History Colorado, along with the Governor’s Women’s Vote Centennial Commission and great collaborators across the state, has organized discussions and events to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment and deepen our understanding of voting rights and women’s history.

Through these conversations and collaborations, we have grappled with the questions of who was included in this historic moment and who was not. As we approach Women’s Equality Day, which commemorates the ratification and certification of the 19th Amendment, we think it is important to explore the simple and complex answers to these questions.

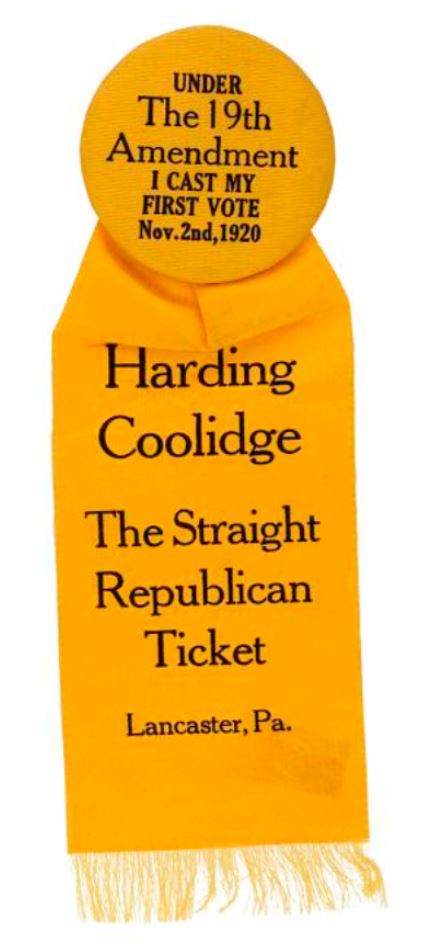

Badge celebrating the passage of the 19th Amendment with a vote cast for the Harding-Coolidge ticket

National Women’s Suffrage

The 19th Amendment states simply that US citizens could no longer be prevented from voting based on their gender. The actual language of the amendment clearly states: “The right of the citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

In the political rhetoric of the time, the eradication of gender discrimination in voting was labelled as equal suffrage. While the 19th Amendment made great strides in expanding voting rights to technically include half of the adult population, it did not address other forms of voter discrimination. Some of these voter exclusions existed in 1920 and some were invented along the way.

Voting access is a constant tension in US history. For example, the 19th Amendment didn’t exclude Black women but Jim Crow laws and the Jim Crow South used a number of policies along with violence and intimidation to keep African American men and women from voting. Also, since voting was tied to citizenship in both the 15th and 19th Amendments, those in power changed and manipulated the definitions of “citizen” as a way to prevent people from voting, while English-only ballots also excluded voters.

We can better understand the history of racist prohibitions on voting through a timeline of both exclusionary laws and acts designed to eradicate discriminatory policies. Here are a few historic laws—enacted post-19th Amendment—that illustrate these disenfranchisements:

- 1922 Supreme Court rules that people of Japanese ancestry are not eligible to become naturalized citizens.

- 1943 The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prohibited citizenship for people with Chinese ancestry, is repealed in an effort to strengthen World War II alliance between US and China.

- 1946 The Luce-Celler Act allows Filipino Americans and Indian Americans to naturalize and become US citizens; the Act also establishes quotas that allowed 100 people from India and 100 people from the Philippines to immigrate to the US each year.

- 1952 The Walter-McCarran Act grants to all people of Asian ancestry the ability to become citizens.

- 1965 The Voting Rights Act of 1965 suspends literacy tests in the Deep South and provides federal enforcement of voting rights in an effort to eradicate Jim Crow Laws designed to limit African American voting.

- 1970 The 1970 Voting Rights Act prohibits literacy tests in twenty states.

While Indigenous peoples and tribes practiced self governance before American colonization, the path for Indigneous voting rights in America is fraught with obstacles and prohibitions. Here are few dates to illustrate this complex history:

- 1887 The Dawes Act pushes for assimilation by allotting land individually to Native Americans in exchange for citizenship (after 25 years). The Act required Indigenous Americans to assimilate to the larger American culture and turn away from his/her tribe. The Dawes Act has a number of harmful effects, including the ways it severed tribal control of two-thirds of tribal lands.

- 1924 The Indian Citizenship Act acknowledges US citizenship for all Native Americans regardless of whether they remain on tribal lands or have relinquished tribal membership. Technically, this citizenship should have also enfranchised Native American voters. However, many states use their power in defining voting laws to prevent Indigenous access to voting.

- 1962 New Mexico becomes the final state to enfranchise Native American voters.

In the face of these policies and exclusionary maneuvers, it is important to note that Indigenous women played a notable role in the national suffrage movement. This recent article in The New York Times explains.

Colorado Women’s Vote

In Colorado in 1893, male voters received a simple ballot that asked the question, “Equal Suffrage: Approved or Not Approved.” This historic vote—the first enfranchisement of women voters by popular referenda in American history—specifically removed gender discrimination, but did not remove other forms of discrimination. Colorado’s women’s suffrage bill begins: “That every female person shall be entitled to vote at all elections in the same manner in all respects as all male persons are.”

Women’s suffrage in Colorado addressed gender discrimination but did not eradicate other forms of disenfranchisement. There are a number of key historic figures and dates that illuminate what the women’s vote meant for women of color in Colorado.

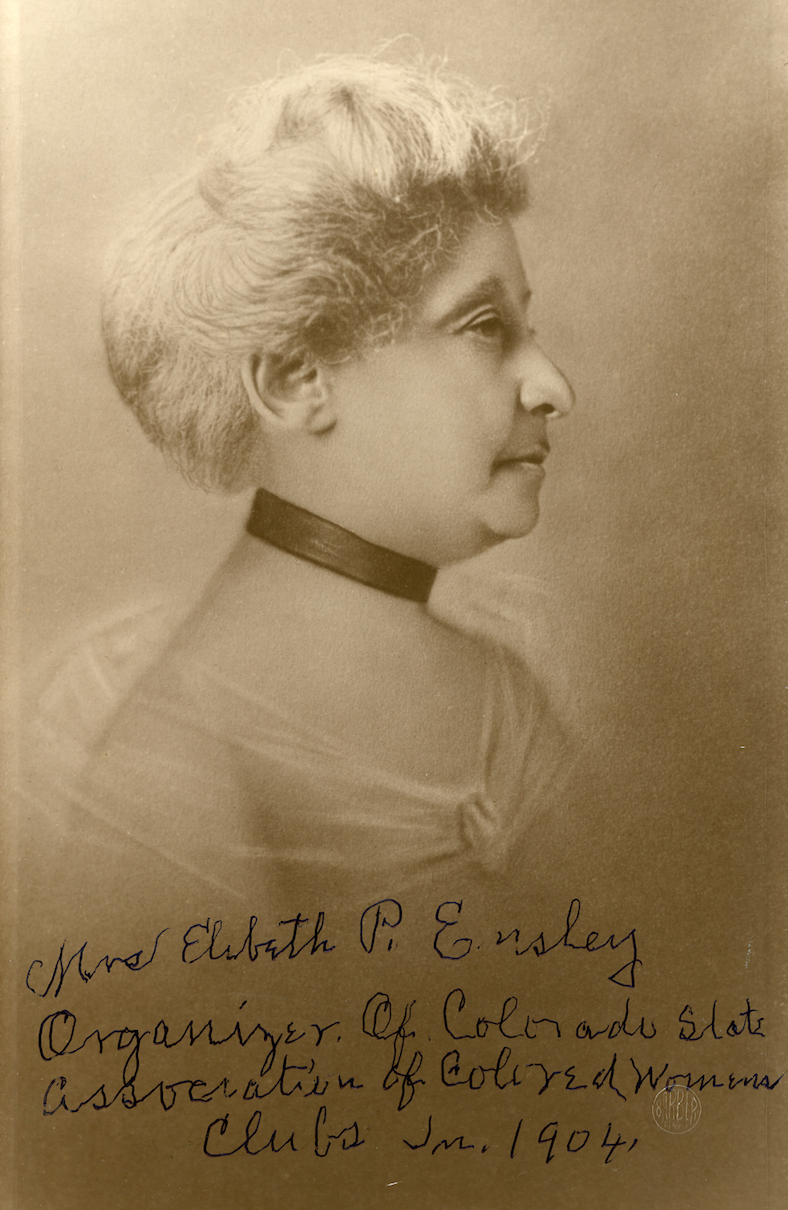

- To understand the access Colorado's African American women had to voting, we learn much from the biography of Elizabeth Ensley. She was a Denver-based African American suffragist who was a leader in Colorado’s successful equal suffrage movement, including serving as the Treasurer of the Colorado Equal Suffrage Association. She recruited other Black women into the suffrage movement and lobbied African American men to approve the ballot issue. Once Colorado women were enfranchised, Ensley founded the Colored Women’s Republican Club to connect other Black women to full participation in their new rights.

- Hispano women weren’t excluded in Colorado’s 1893 law but their enfranchisement is connected to definitions of citizenship. Parts of southern Colorado were Mexico until the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848. For Mexican citizens who suddenly lived in the United States, they had the option to declare citizenship to the US or Mexico. The Treaty presented even more complications for the women who lived in these lands formerly recognized as Mexico because Mexican women had more rights than American women. Citizenship and the rights of the resident women in these lands remained in flux for some time following the Treaty. All of this would have impacted who was enfranchised by the 1893 law. Economic class also played a role in voting access. Wealthy Latina landowners—like the New Mexican women in this Smithsonian article—had a more defined sense of citizenship than Latina farmworkers. It is important to note that two Hispano southern Colorado men—Senator Casmiro Barela (Las Animas County) and Agapito Vigil (Huerfano County)—were early and vocal proponents for Colorado women voting.

- While the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act granted Native Americans citizenship, Colorado did not recognize the voting rights of its Indigenous residents. Here are specific examples:

- In 1936, Attorney General Byron G. Rogers wrote a letter stating that “Until Congress enfranchises the Indian, he will not have the right to vote” (in Colorado).

- In the 1960s, according to the book American Indians and the Fight for Equal Voting Rights, Colorado's Attorney General and legislature reaffirmed the disenfranchisement of Indigenous people living on tribal lands in Colorado by declaring them residents of federal reservations and “not deemed to be ‘residents’ of the State of Colorado for the purposes of elections.”

- Tribal members who lived on reservations could not vote in Colorado until 1970.

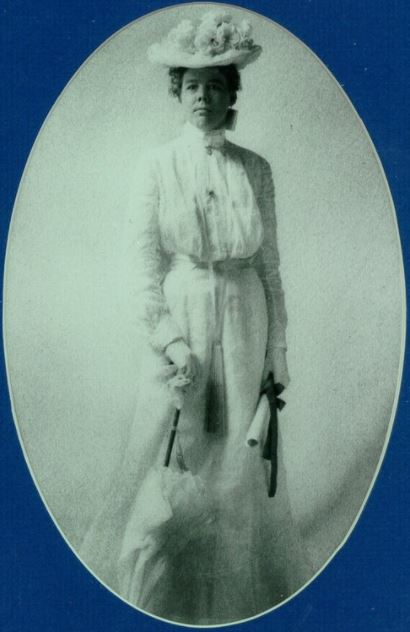

Eliza Burton "Lyda" Conley (Wyandot), the first Native American woman lawyer in the US (1902) and first to argue a case before the US Supreme Court (1909)

The Voting Rights Act and subsequent voting rights legislation expanded access to Indigenous voters, in the same way it did for African American voters. However, Colorado Ute tribal members still faced obstacles to access, including a lack of voter registration sites and permanent polling stations until the early 1990s.

For all of these reasons, today’s scholars and activists warn against framing the 19th Amendment as “equal suffrage.” It is a great and important expansion of voting rights, but many people continued to be excluded. The 19th Amendment was an important moment and a beginning. It changed how we envision the full expression of freedom and who all should be included as active agents in our democracy.