Story

Taking Colorado Day by Day

In conversation with author Derek R. Everett

In March of 2020, History Colorado and the University Press of Colorado published a new kind of book about Colorado’s past: Colorado Day by Day. In it, author Derek R. Everett, who teaches history at both Metropolitan State University of Denver and Colorado State University, looks at a key piece of Colorado’s past for every day of the year—366 days in all.

Everett is also the author of The Colorado State Capitol and Creating the American West. With the publication of Colorado Day by Day, I sent Derek a number of questions about his new book and its particular way of framing the people and events of Colorado’s past. By the time he could answer them—and given the sudden shift to teaching his students virtually for the remainder of the semester, and the historic nature of events that had ensued—a few of those questions had taken on a new kind of resonance.

March 4, 1847: The birthday of Casimiro Barela—by century's end, the most prominent and powerful Hispano in Colorado

Why did you decide to use a this-day-in-history approach for a book about Colorado, and who’s it for?

There’s something curiously compelling about realizing that some big event or famous person took place on whatever date you find yourself occupying on the calendar, back in the mists of time. It’s as if there’s some extra-special connection between the present and the past on such anniversaries, which often lead to celebrations or commemorations, thinking not only about what happened in the past but how those people and events affected the world in which we live. That doesn’t reflect reality, of course—one’s birthday is just another day in the year, ultimately. But the coincidences that reverberate when a date comes up that had something big happen in the past, whether for yourself personally or for the world at large, seems to make the experience all the more real, reminding you that the past was once the present, and our present will someday be the past.

I’ve long been fascinated by this-day-in-history writing, for example when the Rocky Mountain News and Denver Post would print such lists when I was growing up. The thought of writing a book about Colorado in that format was long simmering on the back burner of my brain, and eventually one day I just started pushing forward on it. My intention was to write a book that was enjoyable and accessible to a wide audience, offering snippets of Colorado history that would be as appealing and useful to someone whose family has lived here for many generations as someone who moved to Colorado last week. Think of it as a chocolate box of Colorado history, tasty in individual bites but easy to polish off all at once, too.

It’s a unique approach—unique in the sense that nobody's ever done it before on this scale. What sort of insights came out of the process of looking at Colorado’s past out of order, as it were?

Colorado Day by Day is a kind of Centennial State mosaic, with lots of individual pieces coming together to tell a broad, diverse, complicated, rich story. Even with 366 days (counting Leap Day), there were plenty of mosaic tiles that didn’t make it, for various reasons. For me the most enjoyable part of this project was seeing the ways in which individual stories, people, places, or events stood on their own while linking to others as well. For example, through this project I gained an even greater appreciation for the impact the Sand Creek Massacre, perhaps the worst day in Colorado history, had a century and a half ago and how it continues to reverberate through Colorado. Every story in the book has ties to others, and in a sense I might be better served to use a tapestry as a metaphor rather than a mosaic, considering how interwoven all of these tales have proven to be.

June 15, 1941: Red Rocks Amphitheatre hosts its inaugural concert. Here, the New York Philharmonic performs in the summer of 1960

Any surprises? Revelations?

Many of the stories, people, and so on that appear in Colorado Day by Day were already familiar to me in one sense or another, but I was able to appreciate them even more through the production of the book. Condensing major aspects of Colorado history into a couple brief paragraphs per day forced me to concentrate my efforts in ways that were helpful and useful, not only in this project but for me as a writer and historian in general.

One goal I set for myself from the very beginning was to ensure that stories from each of Colorado’s sixty-four counties appeared in the project. Denver so often dominates the narrative of Colorado history, and for good reason considering its economic, political, and social influence. But if this was going to be a book about the state as a whole, I wanted to demonstrate how stories from across our invisible rectangle interact with each other and reverberate across our boundaries regionally, nationally, and internationally. Denver shows up a lot in Colorado Day by Day, as one would expect, but I believe I’ve shown how important and interesting tales from the plains, peaks, and plateaus alike come together to tell the broader story of the Centennial State.

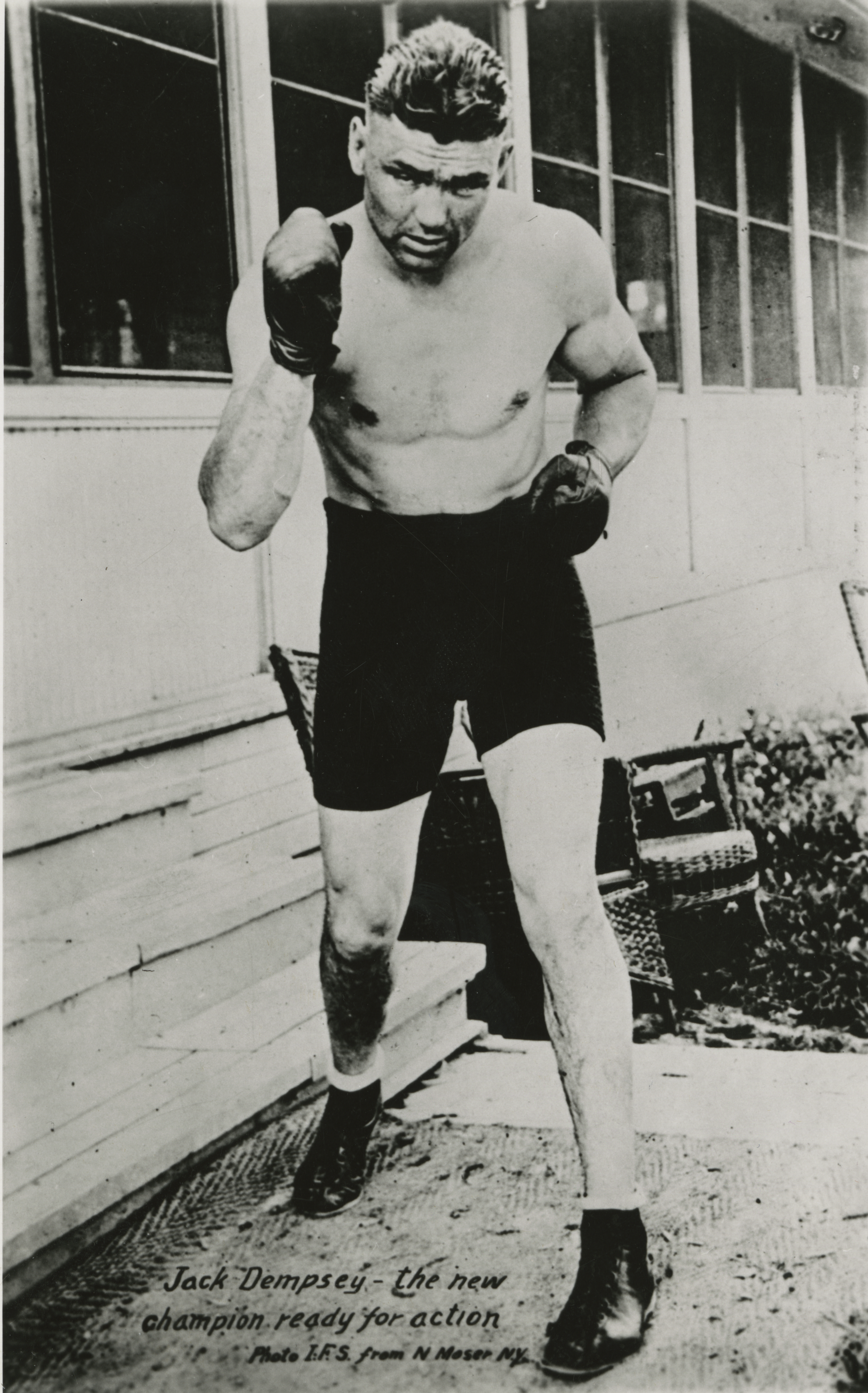

September 6, 1920: Jack Dempsey, the "Manassa Mauler," defends his title as world heavyweight champion

We tend to think of history as a series of currents, of events one rolling into another into another. Did this project change your own view of history?

Researching and writing Colorado Day by Day felt at times like being a chef, figuring out which ingredients to add to make the most delicious, satisfying stew of Colorado history. At other times, I felt like a detective, searching out puzzle pieces to fit together to understand a bigger story, while recognizing that plenty of pieces weren’t going to fit in the picture (or a book less than a thousand pages long). I tell my students at MSU-Denver and CSU that history is a blend of the fundamentals (who, what, when, where), context, and significance, and trying to cover those bases in entertaining and informative ways in relatively short entries put my skills as a historian to the test.

In a feature article in the spring issue of our Colorado Heritage magazine, you (and fellow historians Steve Leonard and Duane Vandenbusche) shared insights about how the 1918 flu outbreak can inform the times we’re living in. What other vignettes in Colorado Day by Day might have lessons, or resonance, for our times?

There are many entries in Colorado Day by Day that resonate in the moment, both in regards to the coronavirus pandemic as well as the civil rights protests that have swept the country and the world since George Floyd’s death in Minnesota in late May 2020. There’s an entry for the Spanish influenza, of course, as well as issues of segregation and racism in Colorado’s history with particular impact on African Americans, Latinos, American Indians, Asian Americans, and immigrants of many different ethnicities. Beyond those, I think the format of the book is a useful reminder as we ponder how our own times will be interpreted by future historians. Scholars ask questions of the past, and the questions we ask are shaped in large part by the world around us, so there will undoubtedly be new ways of thinking about and interpreting the past that come from the pandemic and the protests that have become such central factors of life in Colorado and beyond in recent months.

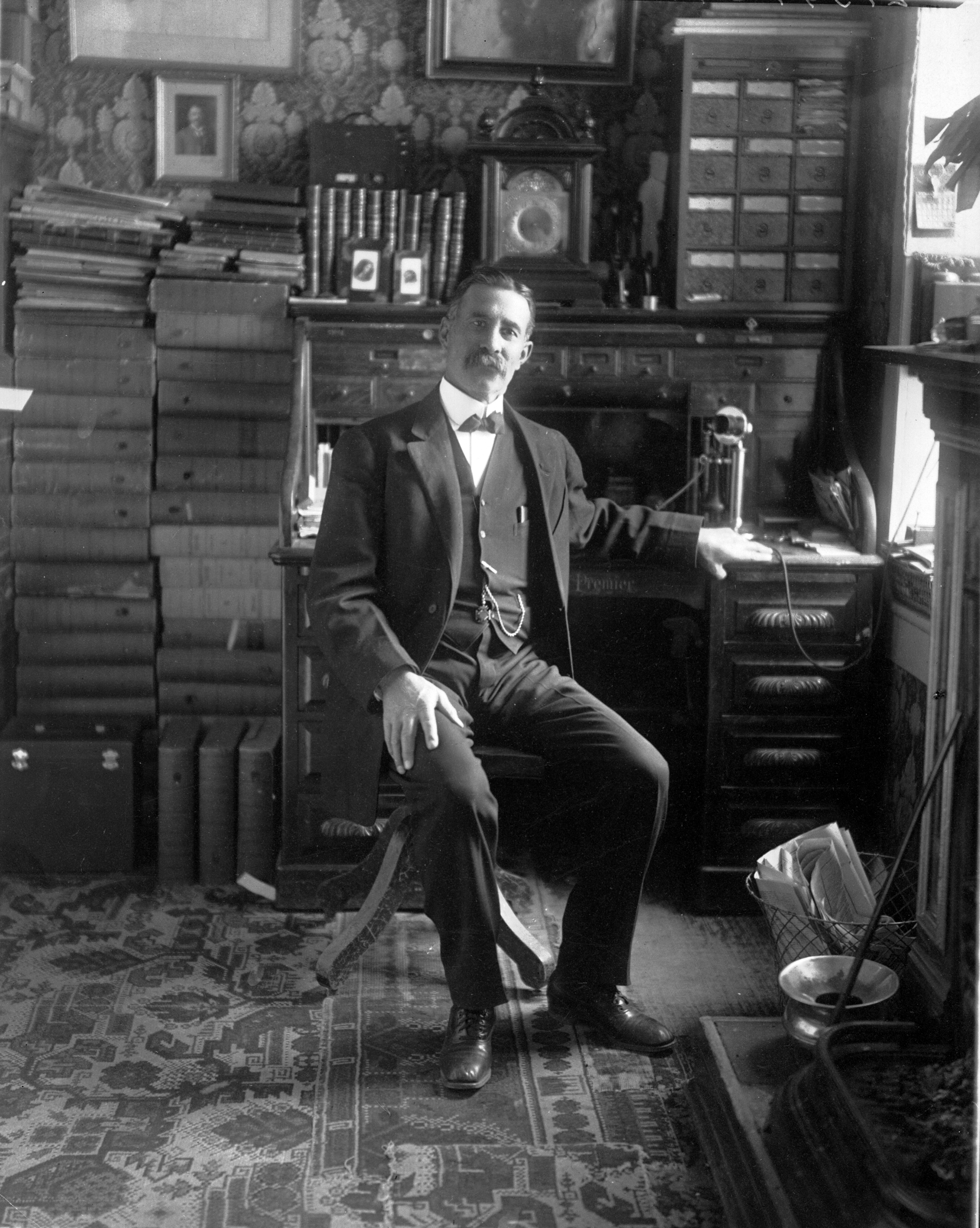

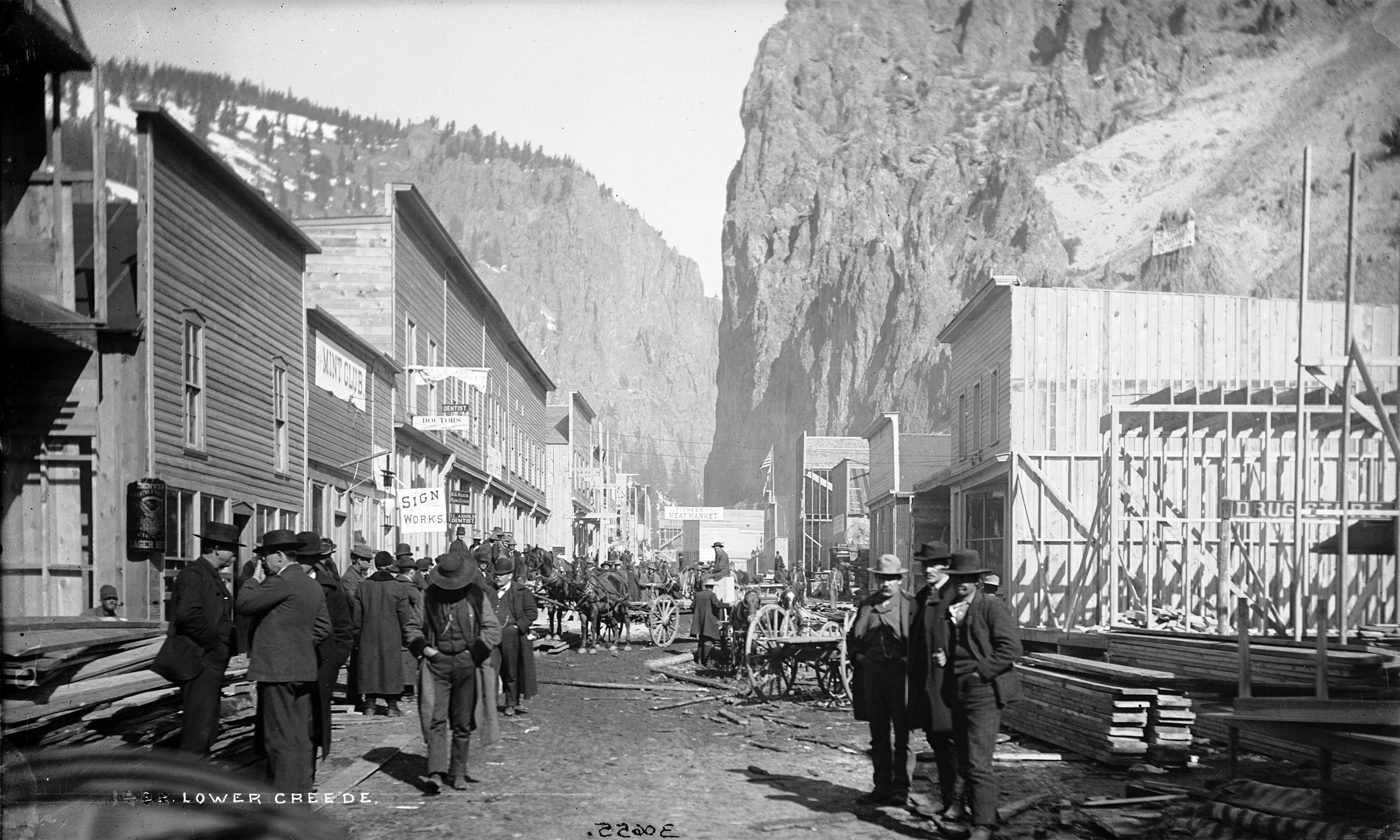

October 2, 1889: Two prospectors clamber down a hillside in today's Mineral County and strike a vein of ore, launching Colorado's last great silver rush. Shown here is the town of Creede, still building in the boom days of the early 1890s

History is rarely tidy, so there must have been some key events that happened on the same date of their respective years. Did you have to make any painful cuts? Did you cheat?

It took me about four or five years of work to put this book together, starting with the compilation of a timeline and then writing entries for each date. As I researched and wrote the entries, there were times when I realized I had an event or person on the wrong date, and if I wanted to include their story that usually involved a massive amount of reorganizing, changing other dates and reassigning them to different days on the calendar. Going back to the tapestry metaphor, every time I tugged on a thread, seventeen others came loose, and it was a devil of a time to reassemble everything. For that reason, I like to say that Colorado Day by Day was the most enjoyable project I’ve ever done, and I’m thrilled beyond belief that I’ll never have to do it again.

There were a lot of challenges in making the timeline, both initially and as I proceeded with writing and tweaking. A good example is April 20. There are two events in Colorado history associated with that date, the Ludlow Massacre in 1914 and the Columbine High School shootings in 1999. A book like this couldn’t include one but not the other, but only one event could claim April 20. For several years Columbine held that spot, while Ludlow was recognized two days later when the first relief parties arrived at the site in Las Animas County. But in one of those many thread-pulling experiences, it eventually came to pass that I had to put the Ludlow Massacre back on April 20. The Columbine shootings couldn’t just pass without acknowledgment, though, so I found a new home for them on August 16, the day classes resumed at the high school nearly four months later. In the end, I came to like that arrangement better—Columbine’s story was associated with a more optimistic, hopeful day than April 20, and Ludlow carried the burden for one of the darker dates on the Colorado calendar.

I hesitate to say that I cheated on any entry, but there was a little massaging in places to accommodate the tapestry of interlocking dates and stories. For example, there are some events—like Colorado being awarded the 1976 Winter Olympics, which we later refused to hold, and the closing of Fannie Mae Duncan’s Cotton Club in Colorado Springs, an iconic example of racial interaction—that appear in the book on the day those stories broke in the newspapers in Colorado rather than the exact date they really happened. I consoled myself with the knowledge that I was recognizing the days that Coloradans would have learned the stories, so that would suffice.

October 11, 1873: Arthur C. Peale discovers ancient plant fossils from a prehistoric lakebed in today's Teller County, leading to the preservation of several dozen petrified tree stumps as Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument

In only one case did I take a little historical license. I needed to cover Charles Autobees and the Arkansas River valley, but every specific date I could find related to his story was already used by an event I couldn’t move to a different date without completely disintegrating the tapestry. I knew that Autobees had moved onto his land claim in what’s now Pueblo County on February 20, 1853, but I had something for February 20 that couldn’t be relocated but couldn’t be tossed entirely either. So I took some poetic license, and assumed that Autobees and his pals were probably tired when they arrived, and so started the real work of building their ranch the next day, February 21, the date it holds in the book. Please don’t judge me too harshly.

When I started Colorado Day by Day I was daunted at the prospect of finding 366 stories to tell, but as the project went on I discovered how incredibly few opportunities that really is, and how many tales fell by the wayside. There were many, many, many painful cuts to the timeline as the book unfolded, and there were even a few complete entries written that had to be abandoned because other, more essential stories cropped up and something had to fall on the chopping block. (Interestingly, the non-fatal beheading of Mike the Headless Chicken wasn’t one of them. In fact, his was the very first entry I wrote for the book, and my author’s photo on the back is of me standing next to his statue in Fruita. I have a special place in my heart for Mike.) I have a list, safely hidden deep in my electronic files, called “The Didn’t Make Its,” which has all the stories that for one reason or another had to fall by the wayside. If I really want to test my sanity someday, I could write a second edition incorporating those stories and more that happen in the meantime or are exposed to the light of day through new research and interpretation. The more time passes, the more I’ll forget the pain of weaving this particular tapestry and might be open to making a new one. For the moment though, I’ll live with the scars and nightmares and content myself with my untold-story list of shame.

How are your students seeing these times we’re in? Do you want to talk about the challenge of teaching history remotely? Or...do you not want to?

I teach at MSU-Denver and CSU, two very different schools with, in their own ways, diverse and engaging students. Plans for the spring semester were tossed in the blender around spring break, when schools began closing down due to the coronavirus pandemic. I told my classes at each institution before we departed please to be patient as we all worked our way through this, since faculty and student alike were flying by the seat of our pants. My eight courses overall this spring became all online ones, which lacks the dynamic potential of face-to-face teaching, so that definitely affected the experience. I’m teaching online courses through both universities this summer, and will be almost entirely online in the fall, with one Civil War course at CSU held in the student center ballroom to accommodate the class size in a safely large space. I’m grateful that the administration at CSU recognized how important a Civil War history course is right now, as we’re reckoning with historical memory in such powerful ways.

More than anything, I want to say how impressed I’ve been with the flexibility of my students, with their ability to develop critical thinking skills and incorporate the past and the present during the twin situations of pandemic and protest that have roiled our world in recent months. The adaptability and capability of my students has been an inspiration, and I’m exceptionally proud of them. The generation that’s in college right now grew up in the shadow of 9/11, the war on terrorism, the Great Recession, the myriad controversies of the Trump administration, the most widespread global disease outbreak in a century, and more. These are some tested, tempered young women and men, and I have great confidence in their generation as they emerge to play an ever more engaged role in world affairs. They’re going to do great things, of that I’m confident; after all, they already are.

After reading your book, which looks at Colorado’s past non-chronologically, is there a bigger something you’re hoping the reader will take away?

December 5, 1913: Colorado starts digging out from its biggest blizzard ever

Perhaps my fondest wish for a reader of Colorado Day by Day is to recognize both the forest and the trees, as it were, the individual stories that make up Colorado history as well as the broad narrative made up of these threads, these pieces of the mosaic. If knowing that something important happened on a specific day—your birthday, anniversary, or the particular date on the calendar you happen to occupy at the moment—helps develop your appreciation not only of that individual story but of the broader tale, I’ll consider my efforts a success.

Lately, I’m finding a sort of comfort in reading the classics. They help me keep the long view—the sense that come what may, we endure. What are you reading these days?

I like to dabble in classics as well; like with Colorado Day by Day, they help ground us in the present by reminding us of our roots in the past. That being said, most of my reading right now is research materials rather than pleasure reading. For someone who teaches in two university history departments, usually eight or nine courses a semester, the coronavirus pandemic sequester is the closest I’ll ever come to a sabbatical. I’m doing my best to get research and writing done during the hiatus, and have been more productive in recent months than I have in the past few years. My wife, Heather, and I read to our nine-year-old daughter Louisa every night before bed, so that certainly counts as pleasure reading. We’ve been rereading what I’d consider modern classics—the works of Roald Dahl—and I’ve been introducing her to some more weighty, thought-provoking pieces. This week we’ve been working our way through George Orwell’s Animal Farm, which I hadn’t read since high school. It’s a sobering book, one that has proved exceptionally useful in exposing Louisa to complicated and controversial issues in an engaging way. We’ll probably turn to Mark Twain soon, some Tom Sawyer or Huck Finn.

You’re always writing. What’s next? “Travels with Louisa”?

My daughter Louisa is my constant traveling companion, although that’s been curtailed this year by the coronavirus pandemic of course. There are more than a few books in our adventures, to be sure. I have a couple projects in the hopper at the moment. I’ve been associated with the Colorado State Capitol as a guide and researcher of its stories since 1997, and have an ongoing project in the works there with the capitol’s architect, Lance Shepherd, about its recent restoration and historic preservation work. I’m also working with friends in Wyoming on a coffee table–style book about their recent capitol restoration project, a marvelous triumph in Cheyenne.

The research and writing project demanding the greatest amount of my time and attention right now is one that I’ve fiddled with for about a decade now. It’s an investigation of Colorado’s thriving beet sugar industry (which shows up several times in Colorado Day by Day) and its dependence on ethnic and immigrant labor in the early twentieth century. The arguments about race and economics that roiled Colorado communities a century ago echo today, as does the occasional eruption of nativism that lurks like a shadow throughout American history. I’m hoping to make some big progress on this project, tentatively titled Bittersweet, while most of my teaching is done online this year. I’ve made more headway in the past few months than I have in the past few years, and hope to keep the momentum going. It’ll get a lot easier when I’m allowed into libraries for research again; I haven’t broken into any closed by the pandemic yet, but if you see headlines about a guy arrested at a university library for breaking and entering, trespassing, and unauthorized use of a microfilm reader, you’ll know it’s me.

Find Colorado Day by Day at your local independent bookstore or order from the University Press of Colorado.

Top image: January 29, 1906: After years of trying, a group of ranchers inaugurate the National Western Stock Show, an ongoing annual tradition with an optimistic future. History Colorado, 10051839