Story

The Post-NAGPRA Generation

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), Thirty Years On

Reader, I have struggled to complete this reflection on the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

I’ve struggled because NAGPRA is a complicated piece of legislation to describe. I have struggled because the historic relationship between archaeologists and Native peoples in the United States has been one of harm and distrust. I have struggled to write this because I truly love archaeology and believe that it can be a force for social justice. I have struggled to write this because I know how often archaeology and archaeologists fail to be that force. I have struggled to write this because I wanted to write about how far we have come even when I know how far we have yet to go. Just today High Country News reported how a relatively recent excavation on Bureau of Land Management land by a public university in California failed to properly notify, or return, Indigenous remains to their descent communities. Our crimes of the past continue.

In 1990, when the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was passed, there was a lot of fear in the archaeological community that it would be detrimental to science. NAGPRA requires federal agencies, museums, universities, and other cultural institutions receiving federal funding to return human remains, funerary objects, and culturally significant items to the associated tribes. These human remains and sacred items had been collected for centuries: counted, weighed, boxed and stored. While there were researchers who collected data from the graves they excavated, many did not.

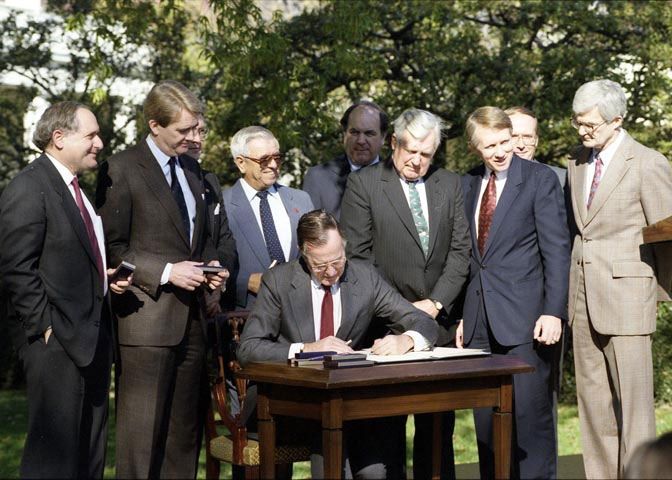

President George Bush signing the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act in 1990

As archaeology is a destructive practice, there is a strong commitment to holding on to artifacts in perpetuity—forever. There is a sense of responsibility instilled in us to preserve items for some unknown future researcher. This was a central argument against returning human remains: in case someone else wanted to study them. Another primary argument of the anti-NAGPRA archaeologists is that the retention of human remains is necessary for important scientific inquiry. The truth is that archaeologists had the opportunity to gather data from these remains, and for the most part, they never did. Remains had been hoarded, in some cases for decades, without anyone pursuing research. In the 1980s and 1990s researchers were just having the conversations around the appropriateness of excavating human remains at all, and of what role tribes and descendant communities should have in decisions around excavation and investigation. Before that debate could mature, there was public outcry over sensational episodes of grave robbing, such as Slack Farm in Kentucky, where 450 graves were looted. How the legislation came to focus so thoroughly on federal agencies and museums is a different story, although it does speak volumes that the United States Congress could see professional archaeologists and amateur treasure hunters in the same broad lens.

Seemingly overnight NAGPRA became an important piece of civil rights legislation. While the law is fairly narrow in scope only affecting federal agencies, those who receive federal funding, and federally recognized tribes, it is probably the most widely recognized law pertaining to Indigenous material culture in the United States. Because returning ancestors to descent groups is not a passive or one-way activity, NAGPRA is often a touchstone that nurtures relationships between tribal professionals and western researchers. Returning ancestors to their descendants requires engagement, consultation, and collaboration with tribal governments, Elders, and tribal cultural professionals. While some anti-NAGPRA archaeologists were alarmist that NAGPRA was the first step to emptying museums, that has not occurred. Over the last thirty years what we have seen, instead of an emptying of museums, is a thoughtful collaboration between all these entities. We consider how to move forward together, what needs to be returned immediately, and how museums can be good stewards on behalf of tribes for other objects.

Panelists from the 2019 Saving Places Conference on the Bent Tree Controversy. These kinds of collaborations have grown out of relationships built from NAGPRA consultations.

NAGPRA has been central to interrogating the relationship between white science and descendant communities. While NAGPRA specifies how the remains of Indigenous people are to be treated, it hasn’t been lost on archaeologists and museum professionals that perhaps these respects should be extended to other remains as well. Social movements such as Black Lives Matter have only amplified these practices, increasingly pushing reluctant institutions to empty the collections of all human remains. These conversations around what the role of a museum is or what our responsibility is to the descent communities, has become mainstream. It’s part of the activist discourse, artistic critique, and even pop culture. There were few people who could watch the opening scenes of the 2018 film Black Panther without feeling some schadenfreude when Killmonger executed a daring heist of a Wakandan artifact.

For post-NAGPRA researchers, those of us who were educated in the new world the law created, NAGPRA has fundamentally changed the way we think about our work compared to our predecessors. Most importantly, it has changed our definition of community. At the same time that NAGPRA has been maturing, an increasing number of archaeologists come from the communities that were once seen only as laboratories of study. Collaborations between researchers and descendants are increasingly de rigueur for archaeological and museum projects. NAGPRA has challenged all of us to consider what our priorities should be as scientists, and what it means to do good work. There are still struggles. To date, nearly 70,000 individuals have been returned home. But it is estimated that another 130,000 ancestors are still lingering on museum shelves, waiting to be returned to their descendants. While some institutions have repatriated all the Native remains in their collections, others have yet to begin. Thirty years on, not everyone is sold on the legislation and debates still rage around the effects of returning human remains. Personally, I am embarrassed at the colonial practices of collecting bodies. I can’t prioritize the needs of some hypothetical future researcher over the flesh and blood people I stand next to today.

A generation ago, very smart and compassionate archaeologists, Native activists, and museum professionals transformed the way we do archaeology in this country. The transformation isn’t yet complete. Incidents such as the University of California-Davis case highlighted in the opening paragraph illustrate why NAGPRA is vital to ethical work. But we’ll get there. I struggle to believe that we can’t.