Story

To Protect the Community and Preserve Cultural Ways

Restoring Healthcare Equity in Indian Country

The Covid-19 pandemic has been especially deadly for American Indians and Alaska Natives. With the arrival of the vaccine, the executive director of Denver Indian Health and Family Services feels the urgency of protecting tribal communities and culture—and sees reason for hope.

The early morning darkness is quiet and calm. Coffee is brewing as I open my laptop to address emails that dawn a very productive day. I am the executive director of Denver Indian Health and Family Services, Inc. (DIHFS) and a member of the Hopi tribe of Shungapavi, Arizona. These early mornings allow me to meditate, reflect, and strategize all the decisions of running a health care center, immersing emergency response from Covid-19 into its regular practice.

The clinic is contracted under Title V of the Indian Healthcare Improvement Act, providing services to American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) individuals in the Denver area.

President Nixon sitting between tribal leaders during the development of the Self-Determination Act.

In the '70s, my father worked at the Coalition of Indian Controlled School Boards in Denver when a lawsuit against President Nixon's administration succeeded by releasing impounded Indian education funds. The outcome of this lawsuit funded back into Indian-controlled school districts and allowed tribes to begin the development of their educational institutions. The coalition is credited as the reason the “638 law” is entitled The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, or Public Law 93-638. Like my father, my siblings have dedicated their careers to working in Indian Country, providing equitable healthcare services, and advocating health policies across the United States.

The legacy of my family's social and political work has instilled resilience that has allowed me to continue the hard work required to run a health center addressing health disparities for AI/AN individuals. One year into the pandemic has brought on new challenges and insights into the future of DIHFS. Reflection of history brings forward a new direction in healthcare and new beginnings of serving the AI/AN community.

American Indians/Alaska Natives have been vulnerable to diseases and epidemics going back to the fifteenth century, when European interactions resulted in a cataclysmic disease in Indigenous populations. The lack of healthcare infrastructure was profound in death and extinction, while AI/ANs died in massive numbers from smallpox, influenza, tuberculosis, measles, and many other health factors. Indigenous people had no immunity to these diseases, and thousands of AI/AN lives were taken.

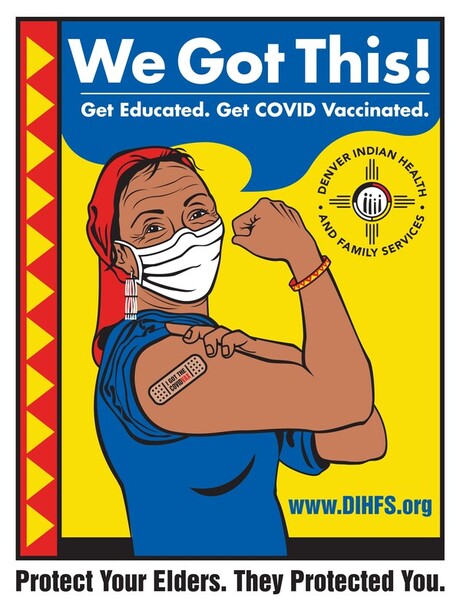

A Denver Indian Health and Family Services poster for their vaccine services.

Among the most vulnerable for Covid-19 are AI/AN individuals due to long-term inequalities, high poverty rates, and high rates of underlying medical conditions. When the virus entered tribal communities, it created a surge and took many AI/AN lives. Healthcare infrastructure is still lacking and cannot keep up with the demand needed to address this health crisis. Access to mental and behavioral health services is now more critical than ever. If more resources are not provided, the high level of health needs for AI/AN that already exists will become even greater.

For this reason, our local governments’ support is essential in addressing the devastating impact of historical trauma carried through the Covid-19 pandemic. Rebuilding trust and collaboration in the aftermath of trauma is vital to restoring hope for our AI/AN communities. The Colorado Commission of Indian Affairs has provided a sounding board to hear community leaders' struggles as they navigate these challenging times. A communication campaign developed through the commission’s Health and Wellness Committee allowed an opportunity to communicate to the AI/AN community through channels that are not threatening to the AI/AN population.

At DIHFS, we have embraced a new platform of healthcare. Telemedicine has become an ideal and essential constituent to care delivery to our families. Mobile health is on the horizon, which will eliminate barriers in getting to our clinic.

Now, DIHFS is receiving Covid-19 vaccine supplies from the Indian Health Services. The Urban Indian Health Institute surveyed vaccines in urban areas and determined that "the primary motivation for participants who indicated willingness to get vaccinated was a strong sense of responsibility to protect the Native community and preserve cultural ways."

DIHFS has partnered with Denver Indian Center and set up a vaccine clinic in their gym. Partnerships with the center and 9Health, a community nonprofit focusing on improving health, provide the infrastructure needed to vaccinate up to 300 individuals at each event.

Vaccinating elders and their families will allow us to preserve our culture and restore trust in our community. Those who have passed took history with them; prioritizing those still with us is crucial. Seeing elders enter our door brings joy to our staff. Hope of seeing their loved ones again is gleaming in their eyes. Trust is being restored.

As I enter the DIHFS clinic's doors at 2880 West Holden Place in Denver’s Sun Valley neighborhood, I am prepared to take on new challenges in the future of health delivery. Blueprints of clinic expansion lay upon my desk; hand sanitizer, disinfectant wipes, and face masks are scurried in different corners of my office to ensure best practices are in place. I look at a photo on my desktop monitor of my dear mother, who passed away in October, reminding me of courage, strength, and love. We’ve got this! Get vaccinated!

Gina Cammarata gets the first round of a Moderna COVID-19 vaccine at the Denver Indian Center, part of the second wave of prioritized shots in the city. Jan. 8, 2020.

This article is part of a series through a partnership with the Colorado Commission of Indian Affairs to elevate Indigenous perspectives and reflections. For more in The Colorado Magazine:

Vision and Visibility

Kathryn Redhorse, director of the Colorado Commission on Indian Affairs, reflects on 2020 as a potential turning point in American Indian and Alaska Native communities’ long struggle for visibility, acknowledgment, and social justice.

Collective Loss, Collaborative Recovery

Ernest House, Jr. (Ute Mountain Ute) comes from an extremely long line of environmental stewards. In times of environmental disaster like Colorado’s wildfires of 2020, he sees opportunities to work together. “The threats to our lands are intertwined, but so are the benefits of protecting them,” he notes.

The Crisis Affecting Indigenous Women

Indigenous women face some of the most shocking statistics of violence of any group. Monycka Snowbird shares the historical trauma that haunts Indigenous women to this day.