Story

The Colorado Women of the Ku Klux Klan

Editor's note: In this article, originally published in Denver Inside and Out (History Colorado, 2011), Betty Jo Brenner illuminates the history of women's roles in sustaining white supremacy in the early twentieth century.

In the 1920s, from Maine to California, in the cities and in rural communities, large numbers of men and women joined the Ku Klux Klan to promote the cause of 100 percent Americanism. They believed the United States needed to be saved from the influences of recent immigrants, African Americans, Catholics, and Jews. In Colorado, Klan membership numbers reached as high as 35,000 men and 11,000 women.1

Little has been written about the Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK) in Colorado or the organization’s leader, Laurena Senter, who later became a pillar of the Denver community until her death in 1986. From the 1940s through the 1970s, Mrs. Senter served as the president of clubs and organizations, including the Colorado Federation of Women’s Clubs, Colorado State Federation of Garden Clubs, and Women’s Club of Denver. She was a certified professional parliamentarian who attended the University of Denver and Barnes Business College. From collections acquired from worldwide travels she created the Senter Friendship Christmas Tree, with its 1,000 lights and 4,000 glass ornaments. The tree was displayed for public tours in her home at Christmas time and later at Kathy’s Import Chalet on South Broadway.2

Three members of the KKK stand near a burning cross at night.

Mrs. Senter’s husband, Gano Senter, was also a high-ranking member of the Klan. He served as the Great Titan of the Northern Province (which meant half of Colorado) of the Colorado Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.3 Together, the Senters immersed themselves in the Klan movement. Laurena’s meticulous attention to recordkeeping and preservation of Klan records reveals much about the inner workings of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan in Colorado.

According to historian Nancy F. Cott, the quest for women’s suffrage was embraced by most women, uniting women for the first time.4 Their progressive ideals were closely tied with suffrage, temperance, and social work. As women asserted themselves in what Estelle Freedman calls “institution building,” they sought their own networks to nurture their culture and well-being. Women’s fraternal organizations and clubs came into existence in the late nineteenth century. Many were formed as auxiliaries to men’s organizations, which emerged during the same period.

Historian Robert Goldberg points out that women’s goals could be progressive and racist at the same time.5 Such was the case with the Women of the Ku Klux Klan, which came into being on June 10, 1923, in Little Rock, Arkansas. Lulu Markwell, the first Imperial Commander of the WKKK, was an Indiana native living in Arkansas while presiding as president of the Arkansas chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). Starting with 125,000 members, the WKKK spread quickly to thirty-six states, increasing its membership to more than one million women nationwide by 1924.6

Ku Klux Klan members march down Larimer Street in Denver, 1926.

The men’s and women’s Klans grew in much the same way. Women recruiters, called “kleagles,” were sent out to spread the message of patriotism and Protestantism. At first recruiters summoned wives, mothers, daughters, and sisters of Klansmen. In time the recruitment effort expanded to include Protestant women seeking to uphold Christian principles and virtues of “true womanhood.” Many women’s patriotic societies eventually folded into the WKKK, including the Ladies of the Invisible Eye, Dixie Protestant Women’s Political league, Grand League of Protestant Women, White American Protestants (WAP), and Ladies of the Invisible Empire.7 Women’s historian Kathleen Blee writes that the Klan lured members by professing to defend morality: “The Klan ranted against the victimization of white Protestant women by Jewish businessmen, sexually sadistic Catholic priests, and uncivilized black men.”8 Women’s Klan chapters often described their mission in self-righteous terms, such as safeguarding public virtues and keeping “the moral standards of the community at a high place.”9

In 1925, as Imperial Commander, Mrs. Senter traveled the state performing rituals and initiations of membership. Women were eager to join the WKKK, partially because of the lure of ritual and mystery and partially because joining clubs was a form of camaraderie for women in much the same way it was for men who joined fraternal organizations. People in rural areas were especially vulnerable to fears of change to the American identity and threats to traditional values. In Pueblo, for example, immigration of laborers into the area from southern and eastern Europe accounted for a significant increase in the Catholic population.

The Colorado WKKK separated from the national affiliation in 1925 due to rumored immorality and corruption in the national leadership. While legal entanglements were growing for Colorado Klan Grand Dragon John Galen Locke, a joint klonklave was called to show support for his leadership. Mrs. Senter presided at this joint klonklave on June 30, 1925, as more than 50,000 Klanswomen and Klansmen gathered at Cotton Mills Stadium (located at Evans and Mariposa in Denver) to decide Dr. Locke’s fate.10 The minutes of the meeting describe the pomp and circumstance frequently played out in the ritualistic order:

The bugle call announced the arrival of the Grand Dragon and his party. The audience arose spontaneously to its feet and began to cheer. The most remarkable demonstration ever given to any living person in the state of Colorado followed. It was the cheers of loyal Colorado Protestants voicing their loyalty and devotion to their great leader.11

The Arkansas-based national WKKK sued the Colorado organization for taxes and fees collected after the breakaway but only succeeded in forcing the Colorado Klanswomen to change their name. Settlement of the lawsuit was not delivered until 1929. The Denver Post reported on April 18, 1929: “Federal Judge J. Foster Symes so ordered that the Colorado organization be entitled to retain $10,000.00, which the women of the Ku Klux Klan of Arkansas had demanded as fees and taxes. Mrs. Senter, Colorado Imperial Commander, said the money will be given to charity.”12

According to Senter’s diary of appointments, there were as many as thirty-five chapters of the Colorado Corporation of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan, based in communities ranging from big cities to small rural towns.13 The list indicates a much broader statewide involvement than historians have heretofore believed. Membership cards indicate there were 11,000 members in the WKKK of Colorado in 1924 and 1925. Most of the members lived in Denver and along the Front Range, but the Akron chapter (Klan #23) in eastern Colorado shows 127 names, while the Alamosa WKKK had 99 registered members.14 Many small towns had chapters, but Denver Klan #1 was the largest Klavern.

KKK women prepare to distribute Thanksgiving dinner baskets to needy Denver families. The baby pictured is Master Richard, an orphan adopted by the group.

Klanswomen believed charitable impulses and benevolence to others defined their role. They delivered Thanksgiving baskets to needy Denver families and gave financial support for the adoption of an orphaned child named Richard. Membership also involved a lot of pomp and ceremony. Colorado Klanswomen participated in parades in full regalia, often unmasked. On occasion they joined the men on Ruby Hill (Denver) and Table Mountain (Golden) to light the cross and proclaim the highest ideal of their order: to keep the United States for white Protestant Americans. Ladies were told not to patronize downtown Denver’s Neusteters Department store because it was “run by Jews” who had publicly stated that Klan trade was not welcome there.15

The ceremonial rituals of “klankraft” took place once a week at the People’s Tabernacle at 1120 Twentieth Street in Denver. Klan headquarters were located at 219 Central Savings Bank Building. Initiation fees of $10 and membership dues of twenty-five cents per week paid for office space as well as a stipend of $150 per year to Mrs. Lillian Baxter for being the Kligrapp, which was the Klan name for secretary. Records indicate that the club was able to amass $15,000 in Cotton Mills savings bonds designated to build a Protestant boarding school for orphans next to Cotton Mills Stadium.16 This orphanage was meant to keep orphan children out of Catholic-supported orphanages.17

The Women of the Ku Klux Klan of Colorado had a constitution, bylaws, memorial ceremonies, a creed, and a list of ideals and beliefs. Their stated purpose was not to inflict physical harm on anyone in the “alien” world but to present themselves as good, charitable, white Christian American women. Their creed was to “avow the distinction between the races of mankind as decreed by the Creator, and to be ever true to the maintenance of White Supremacy and strenuously oppose any compromise thereof.”18

In February 1926, the Colorado WKKK broke from the national organization. For four years it continued as a secret society, meeting at the Pythian Hall on Glenarm and Fourteenth Streets in Denver and eventually at Crystal Hall on 220 Broadway. In 1929 the national WKKK forbade the Colorado women to use the name “Women of the Ku Klux Klan,” so they changed the name of their organization to the Colorado Cycle Club. Laurena Senter described the meaning of the name:

As Webster defines it, it is a revolution of a certain period of time which recurs again in the same order. Our first Cycle was the time of the Revolution of our forefathers standing for liberty, the second cycle was the organization of the Klan in the south, standing for a united government, the third cycle was the Klan as we knew it in 1924–25, and the fourth cycle is the club that we now represent.”19

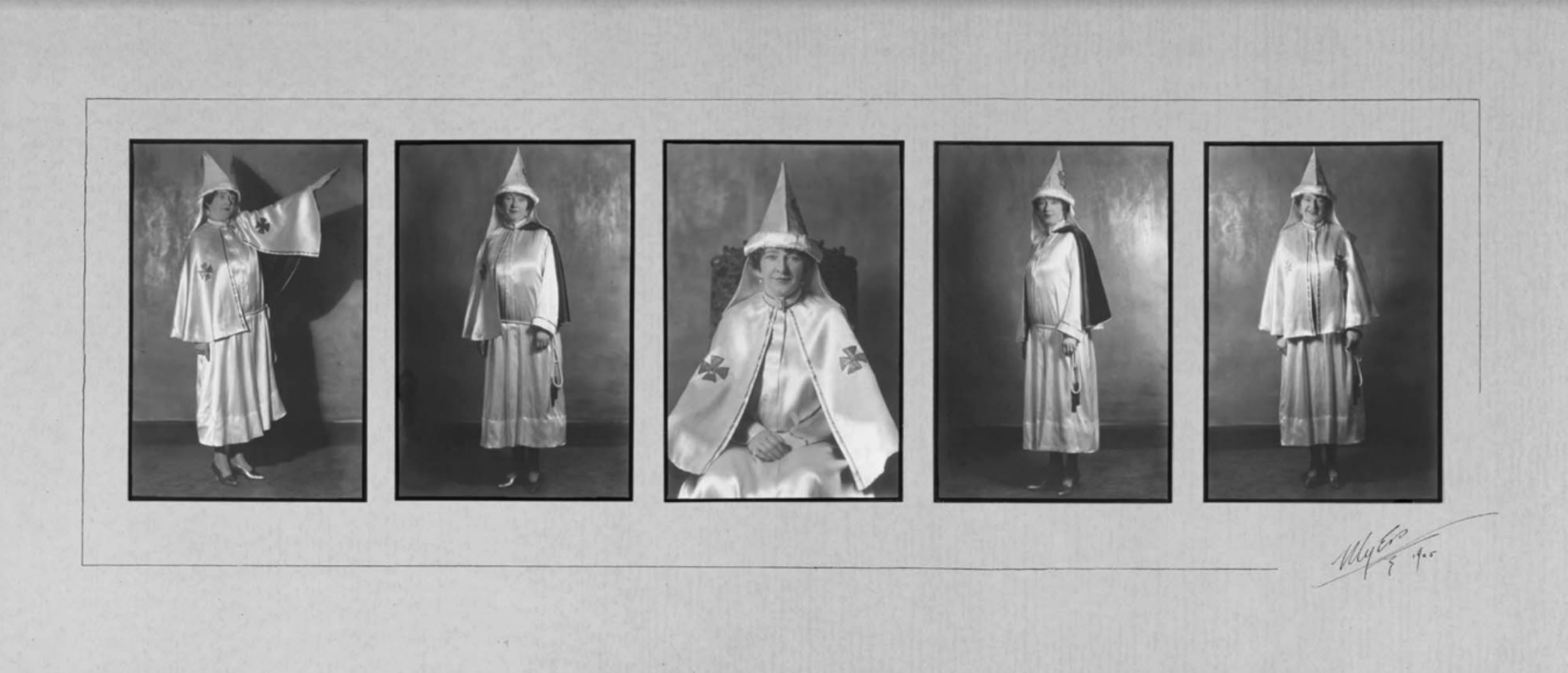

Studio portraits of Laurena Senter in 1925, when she was Imperial Commander of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan in Colorado.

Many people, understandably, thought the name referred to two-wheeled recreation. When a notice of one of the Cycle Club’s meetings appeared in the social columns of the Sunday newspaper, two men appeared seeking admission to what they thought was a bicycling event.

In the wake of the separation from the national WKKK, some Colorado chapters drifted back to the national organization, but for the most part Denver Klanswomen remained loyal to Mrs. Senter and Denver Klan #1. Even without the name, the women of the Klan in Colorado maintained cordial relations with the men’s organization.20 Under the new Colorado Cycle Club moniker, the state’s WKKK continued as an organization until 1945. Eventually the membership roster dwindled to twenty ladies who met at Laurena Senter’s house at 1145 South Logan Street. Dropping the white robe and helmet, they dressed instead in white dresses for special occasions. They met for weekly renewal of friendship. At this time, Laurena pursued her interest in parliamentarian procedure and club work.

In 1929 Laurena Senter wrote an entry in her diary reflecting on the years past and her association with the Ku Klux Klan. Referring to her years as Imperial Commander of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan as “being in the harness,” Senter called those years a “cycle of sorrow” in which she found only work and heartache for her share in the cause. “The order,” she said, “was one of sorrow, and hatred, with ideals of beauty, but too far above the selfish horde that flocked to its portals, hoping for personal gain and glory. We all followed blindly because the cause and ideals were beautiful, and reflected beauty to leaders who were otherwise entirely of mud.”21 In this statement, Laurena Senter laments the failures of the Ku Klux Klan leadership, not the ideological foundations that defined it.

Historians have concluded that the 1920s Ku Klux Klan was a social movement. What is disturbing is how mainstream the ideology was. Newspaper articles reported on club meetings as if they were newsworthy and of interest to everyone. Women paraded unmasked through the streets of Denver, proud to collectively display their unity and stance on patriotism, Protestantism, and purity of race. There were many women’s clubs and fraternal orders before the WKKK. Most were directed at social work, but some were just about camaraderie. It is true that the WKKK belief system was in lockstep with the philosophy of the men’s KKK, but they organized independently while supporting the cause. They executed their objectives in different ways, in keeping with their gender expectations of the time.

In addition to tapping into fear of change, the movement grew in almost every case because of charismatic leaders. Laurena Senter was that leader in Colorado. Even after the Klan disbanded, she never acknowledged her years in the “harness,” as she called it. Her deep involvement was not discovered until her death in 1986, when the family donated her papers to the Denver Public Library.

The question still remains: Did the women who paraded down the streets of Denver in white robes and pointy hats remain white supremacists their entire lives or did their hearts change? Did they keep the secret to themselves and feel ashamed? Or did they feel, as the women in Indiana told Kathleen Blee, “terribly misunderstood”?

Notes

1. Senter Family Papers, WH988, Western History Collection, Denver Public Library, Box 37.

2. Ibid., scope and content.

3. Ibid.

4. Nancy F. Cott, The Grounding of Modern Feminism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987), 59.

5. Robert Alan Goldberg, review of Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s, by Kathleen Blee. Journal of Social History (Fall 1993).

6. Kathleen Blee, Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 28–29.

7. Ibid., 26.

8. Ibid., 71.

9. Ibid.

10. Phil Goodstein writes in South Denver Saga (New Social Publications, 1991) that the Cotton Mills Stadium was originally built in the area west of the Platte River in 1890 by entrepreneurs seeking to create an industrial suburb. Three other mills were built alongside the cotton mill. The area, called the Manchester area, was a failed adventure because Judge Ben Lindsay exposed the business for using child labor. The mill went into receivership in 1904. The Ku Klux Klan bought the cotton mill in the 1920s for massive rallies and outdoor initiations. When the Klan collapsed, the city gained the property for taxes. The Cotton Mills building still stands today, its smokestack bearing the name CUBUSCO.

11. Senter Family Papers, Box 36, FF10.

12. “Klan Women Win $10,000 Suit, Must Change Name,” The Denver Post, April 18, 1929.

13. Senter Family Papers, Box 44, FF10.

14. Ibid., Box 44, FF12.

15. Ibid., Box 36, FF6.

16. Ibid., Box 36, FF14.

17. Ibid., Box 36, FF10.

18. Ibid., Box 36, FF23.

19. Ibid., Box 36, FF19.

20. Ibid., Box 36, FF10.

21. Ibid., Box 44, FF8.