Story

“X,” “XX,” and “X-3”: Spy Reports from the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company Archives

The Colorado Fuel & Iron Company operated fifty-three coal mines throughout Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico, and Oklahoma. For much of its history, these operations made CF&I the largest company and the largest private landowner in Colorado.

Much of the fuel produced at Colorado’s mines provided the raw materials for CF&I’s steel works in Pueblo—the largest and, in the years preceding World War II, the only such facility in the western United States. The mill manufactured 2 percent of all the steel products in the country, and it normally employed a workforce of 6,000 to 6,500 men. The state’s coal-mining activity centered around two main coalfields: the northern field in Boulder and Weld Counties, and the southern field in Huerfano and Las Animas Counties—CF&I’s stronghold. Serving as the hubs of the southern field were Walsenburg and Trinidad, and surrounding each were dozens of coal camps, including Aguilar, Walsen, Segundo, and Valdez.

Of the three men pictured here (presumably state militia), the only one identified is the very tall man—“Shorty” Martinez—who wields a Tommy gun.

Despite the importance of CF&I to the economy of Colorado and the entire American West, the firm is probably best known for its bad labor relations—most notably the Ludlow Massacre of April 20, 1914. On that day, the Colorado National Guard attacked a tent colony of strikers and their families north of Trinidad, killing at least twenty-five people. Among the dead were two women and eleven children, who suffocated in an underground pit when the colony was set ablaze. The massacre at Ludlow severely damaged the company’s reputation and that of its controlling shareholders, the Rockefeller family.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., managing the wealth of his retired father, first bought into the company in 1903. By 1907, the family and its partners controlled CF&I in its entirety. Nevertheless, the Rockefeller interests were so diverse that John Jr. did little to influence the day-to-day operation of the firm. After Ludlow, when he and his family were subject to immense public disapproval, this situation changed.

At Rockefeller’s behest, CF&I implemented a company-sponsored union at the CF&I mines and mill in the years following the Ludlow Massacre. The plan was designed to give workers a voice in the way the firm operated and in the way they did their jobs without allowing workers to bargain collectively through outside unions. The plan proved so successful that by 1920 the United Mine Workers of America (UMW), the largest mine workers’ union in the country, gave up trying to organize CF&I’s miners.

The CF&I Archives include this photograph of “IWW Strike Agitator Leaders in front of IWW Hall, Walsenburg.” Signs in the windows announce the strike and a meeting to be held that night. Likely for purposes of creating individual ID photos, the principals have been carefully isolated and identified: 1. Nick Mavroganis; 2. Frank Mendas; 3. A. S. Embree; 4. Alberto Martinez; 5. Tom Garcia; 6. Nenesio Adillo; 7. John Maes; 8. unnamed; 9. Paul A. Sidler; 10. John Mariega; 11. A. K. Payne; 12. Gumersindo Ruiz; 13. Walter Chatterbock; and 14. Jose Villa. Embree (number 3) figures prominently in the CF&I spies’ reports, and “Sidler,” or Seidler (number 9), was a key strike leader who had been jailed in World War I as a suspected German spy, according to the CF&I memo on page 32. The photograph shows the racial diversity in the IWW leadership; racial egalitarianism was a hallmark of the organization.

Then, another trade organization stepped in to fill the void. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or the “Wobblies”) was among the most radical organizations ever to arise in the United States. Formed in 1905, the group dedicated itself to creating a new communal society by overthrowing the capitalist system of production. Because of the organization’s opposition to World War I, the U.S. government arrested nearly all of the IWW’s leaders in 1918. This nearly destroyed the organization, and the IWW would never again be as strong as it was before the war. Nevertheless, the group did engage in a few major labor actions during the 1920s.

Despite CF&I’s success in keeping the United Mine Workers out of its mines, the Wobblies’ organizing efforts meant that CF&I had to remain vigilant. In order to prevent IWW infiltration, the company hired labor spies. In the years before the New Deal, many companies spied on the unions that wished to organize them. But few such firms were willing to admit to this activity. In 1924, CF&I told an industrial-relations consulting firm that it had given up spying. While this may have been true at the time, either CF&I resumed using spies at some point in the next few years in the face of a major organizing campaign, or it never really ceased this practice.

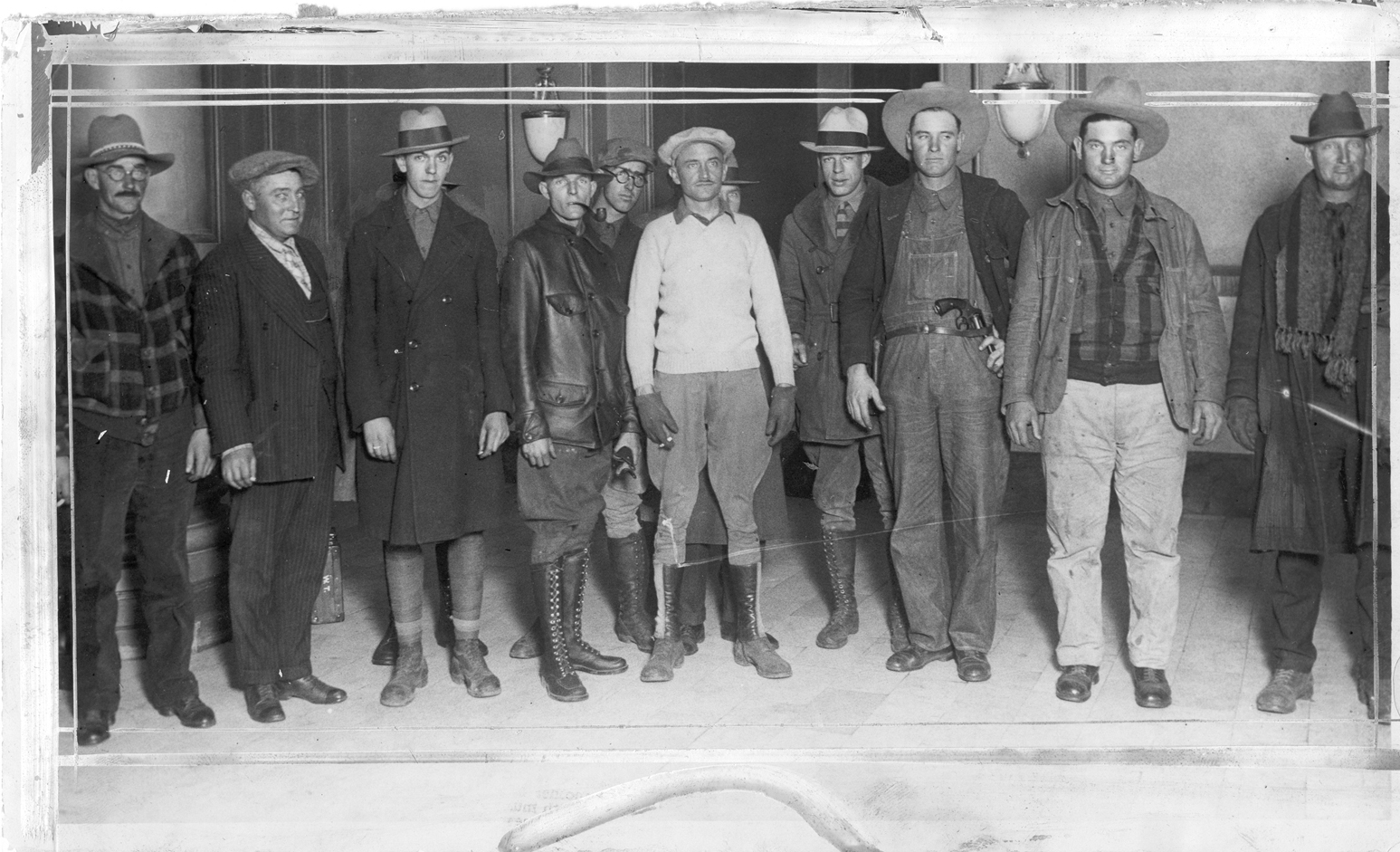

A notation on this group ID photo in the spies’ reports reads, “1. Marian Stemovac 2. John Chavez 3. Joe Whitmore 4. Ed Munden. State Police in rear.”

Because firms that employed labor spies did not want the objects of their espionage or the general public to know what they were doing, actual labor spy reports are a rare commodity for historians. Nevertheless, many such documents survive in the CF&I Archives.

The majority of the spy reports found in the archives thus far pertain to the statewide coal strike of 1927–28. Wobblies in Colorado slowly gained members from 1919 to 1927. Then in August 1927, the union shut down mines across Colorado for two days in a dry run for a larger strike. The Colorado Industrial Commission], a state body charged with mediating disputes like this one, declared that such a strike would be illegal because the meeting that authorized the strike call did not adequately represent miners across the state. On October 18, 1927, the IWW struck anyway.

The union had twenty-one demands in total for CF&I and the rest of the Colorado coal industry. The most important of the demands concerned higher wages, but miners also wanted Saturdays and Sundays off, a six-hour workday, a rent freeze on company housing, free first-aid kits, the abolition of physical examinations, “no discrimination on account of age,” and that labor organizers “be allowed to come and go in company owned camps.” The IWW did not believe that employers would meet all (or perhaps any) of these demands, but it did feel that an extensive list of demands would serve as a good recruiting tool among long-suffering miners.

Officers of the state militia prepare to leave for a strike area, November 7, 1927.

Anticipating trouble, CF&I hired at least three spies in the weeks, months, or years before the strike in order to stay abreast of the Wobblies’ activities. The most prolific of these undercover agents were known as “X,” “XX,” and “X-3.” As it stands, the records are silent about these men’s true identities. The reports give no indication as to whether the spies were hired from private detective agencies or whether they had worked for the company before. Based on the situations described in their reports, it is clear that each spy was employed before the strike began.

The reports not only offer an irreplaceable record of how labor spies affected the course of a major industrial conflict, they provide rare firsthand observations of how the IWW carried out its work. The spies sent or sometimes phoned in their reports from towns with large concentrations of miners, and CF&I’s Pueblo administrative offices transcribed the reports for distribution to key executives. The reports seem to have served a number of ends: to glean intelligence on the Wobblies’ strategies and tactics, to sow disinformation, to disrupt meetings and pickets, and to expose weaknesses in the IWW organization, finances, and leadership.

The first reports excerpted here came in before the strike started, and the last one describes its aftermath.

XX Reports October 11th.

Trinidad Colorado

October 12, 1927I learned that there would be three national Organizers of the IWW [who would] meet at Pueblo Sunday the 16th, and consolidate with the steel mill workers and the agricultural branch of the IWW in northern Colorado. That Svanum [see sidebar] would be the head of all the IWW but he would be subject to the orders of the Strike Committee (state) after the conference held in Pueblo on the 16th.

I also gained information that a speaker and publicity man for the IWW would be sent to Colorado from New York on the 12th of this month to gain the sentiment of the public for the coming strike of the IWW.

Svanum stated that he had put in over $600.00 of his private funds to finance the IWW here in Colorado, stating that he was supplied with this money from a higher power; that he was working for a peaceful revolution of conditions in the U.S?A. [sic] I tried to cause him to say what this power was but could not do so. He said that the IWW was broke and that they could not give aid to the miners when on strike only as it was donated from the outside.

XX’s claims to get his information directly from the “head of all the IWW” in Colorado indicates just how deeply he managed to infiltrate the union. However, it also show’s his failure to fully understand his target. The IWW always demonstrated an aversion to central control over any of its activities. This would explain why a strike committee existed to oversee Kristen Svanum’s activities. Even then, the existence of a leadership committee and a single strike coordinator does not necessarily mean that miners actually took commands from that leadership; many joined the strike for their own reasons rather than to bring about a revolution.

XX Reports Oct. 12 – 8 AM.

The IWW expect to hold a meeting in Walsenburg for the purpose of lining up for the Strike Conference in Pueblo Sunday. If officers could be placed in front of the hall early in the evening, say 6:30 and remain there, it would have a great influence in discouraging the attendance of members as they dislike very much to be seen by a company marshal.

This report shows how spies like XX could hurt a strike even before it began. The strike conference in Pueblo was one of four meetings held across the state during which striking miners endorsed the strike planned by the union leadership for the next day.

By intimidating miners from showing up at the endorsement meeting, CF&I probably discouraged some of the miners from joining the next day’s picket line. In fact, fewer miners showed up for the Pueblo meeting than the meetings organized for miners working at other mine companies in the northern coalfield

But this was not the only form of intimidation directed against striking miners.

XX Phones from Walsenburg

9:30 AM

Trinidad Colorado

October 17, 1927Late Saturday night a delegation of citizens of Walsenburg headed by the Mayor raided the IWW hall, broke the windows and took the furniture, fixtures and literature out in the street and burnt them up. No one was in the hall but Kitto [see sidebar] and he escaped thru the backdoor and made his way up to the C&S [Colorado & Southern] depot where he hid in some shrubbery until train time and then went on to Pueblo. The citizen delegations took the guns . . . in the hall.

Sunday morning the Aguilar and Walsenburg delegates met in front of the hall and went on to Pueblo to attend the conference. Neither Svanum or Franzine [see sidebar] or any of the other leaders were there when we got there. I was appointed temporary chairman and the meeting was called for 1:30 PM. About 12:45 PM, Svanum, Seidler [see sidebar] and Edilla and the balance of the leaders came in and the meeting was called to order. Svanum was chairman.

All the Northern Colorado delegates fought to avoid the strike but Seidler, Edilla and the delegates from Walsenburg and Aguilar over-ruled. Onle [sic] one man from Aguilar tried to avoid the strike. This was Razansky. Smith and myself circulated thru the crowd trying to get them to postpone the strike but without any success and when the vote was called it was unanimous for the strike, even the Northern Colorado delegates voting for it.

About half the miners in Colorado answered the strike call on October 18. The action affected every coal-mining firm in the state to some degree, but the size of the impact varied widely. The strike was strongest in northern Colorado, where CF&I’s competitors employed most miners. More than 50 percent of the miners in Walsenburg walked out, but only seven and a half percent of the miners in Trinidad failed to report to work. At this point, the IWW used pickets and “flying squadrons”—small, coordinated groups of workers who traveled quickly and deployed secretly to miners’ homes to convince men to join the strike.

The activities of the Walsenburg citizens’ group that broke up the union hall were typical of anti-labor organizations during the 1927–28 strike. Yet other antistrike groups helped intimidate strikers in nearby Aguilar at the same time. In late December, a group of citizens would take action against strikers in Trinidad.

Trinidad Colorado

October 21, 1927XX made the following report over phone at 11:50 PM last evening . . .

Svanum told them tonight to get their women out to picket and to pay no attention to the guards; that the guards had instructions not to molest them. The pickets work under sealed orders, that is, they do not know where they are going until after they have gotten into the car just what place they will be sent to. They pretend to search them for firearms before they go out but it is understood that they will not find any if they have them in plain sight.

Since coal miners inevitably lived in housing owned by their employer (no other entity would build housing in the isolated areas where precious minerals could be extracted), mine strikes affected workers’ families as much as they affected the breadwinners. Even if the families were not evicted from their homes (as the women and children who died at Ludlow were), managing family life with no income was never easy. In this instance, since the strike had just started, women were probably joining the picket line knowing that they were less likely than their husbands to be beaten up by company guards.

This report is particularly interesting, as it suggests that the labor organizers understood that their security was compromised and were taking precautions to thwart intelligence leaks.

XX reports by phone 8:50 AM Friday AM:

The A-P and Denver Post reporters think I am a dyed-in-the-wool wobbly and have tried to interview me. In speaking about the alleged carload of arms and ammunition I did not deny this “hokum” but intimitated [sic] that if there was any violence it was against the principles of Svanum and myself and the more select class of “wobblies” but that there was an awfully rough element of “reds” coming into the field and that we might not be able to hold them in hand. Do not know if they are gullible enough to absorb this kind of stuff but can tell better when this afternoon[’]s papers come out. If they play up strong that there is likely to be violence it might hasten action on part of state authorities.

Strikers and their families marching to the mines in the Huerfano County District and calling out ‘scab’ workers, 11/3/27

Up until the 1930s, when government bodies at both the state and federal levels became involved in strikes, they almost always sided with management. This happened at Ludlow and during many other Colorado mining strikes before this one. Knowing this, XX is trying to plant hints of future violence with reporters and thus to scare Governor William H. “Billy” Adams into calling out the state militia before such violence began. Governor Adams resisted this kind of pressure, to a point. He never called out the state militia, but he did send in a group of state law enforcement officers headed by a veteran of the Ludlow Massacre to oversee the strike and intimidate the union.

Emphasizing the ideological elements of the Wobbly agenda only heightened public fears, since the public at this time largely believed that most, if not all, communists were violent criminals.

Walsenburg, Colorado

November 2, 1927“X” REPORTS:

Pickets are to travel in two’s and three’s during the day and make calls at the houses in the camps and around town. Eight men living on Main Street, Walsenburg, near the bridge were intending to go to work but were scared out by the threats. One of these men came to the IWW hall and said if they did not get support they would have to go to work. He told them he had eight in the family and that it would take $30.00 per week to support them. The Financial Secretary offered him $2.00 per day and he said he could not live on that. The Secretary told him then if he would stay away from work he would see that he got $30.00 per week, but that he would have to be active on the picket line.

Ed. Valdez who lives on 7th Street and who works at Cameron Mine will have a delegation of IWW’s at his house tonight to stop him from going to work…

XX Reports by Phone from Walsenburg at 8:30 AM – 11-4-27

They sure knocked the Wobblies over at Walsen Camp this morning. 25 gunmen with Winchesters met them at the gate and held them back. J. B. Childs [see sidebar] and a Greek named George, and another man was arrested for picketing.

If you can get hold of Harris [see sidebar] and Orr [see sidebar] today and have them arrested this will surely bust them up, as they are getting short of good leaders . . . .. . . The flying squadron is actively at work, intimidating women in the houses, telling them to keep their men away from work or it will be the worst for them.

These reports describe the Wobblies’ attempts to keep their colleagues on strike and the actions of local vigilantes to counter these efforts. Note that XX identifies the union’s weakness as a lack of “good leaders.” Because the union inevitably dealt with the worst-paid, least-educated workers, this was a constant problem for their organization. Its loose organizational structure did not help, either.

Strikers and Sympathizers marching through the camp of Walsenburg Colorado, 11/3/27.

X . . . Cr. Butte 11-8-27

We got into the meeting last night just in time to hear Gibb say lay down your tools and strike, already for a vote[.] [T]hen I interrupted Gibb by addressing him as chairman and suggested that I would like to hear from Ross. Ross in the beginning of his talk made Gibb admit that they were representing IWWs[.] [H]e then attacked the IWWs and told them that the organization was not a legal organization and that no corporation in this country recognized them and that the strike was illegal as stated by the attorney general and the industrial commission declaring it so he urged the men to pay no attention to the IWWs and continue at their work[.] [A]fter Ross talked perko Alias Parko took the floor attacking the CF&I and John D Rockyfeller [sic]. [F]ollowing him I took the floor[.] I informed Parko that Rockyfeller was not guilty of what he accused him of and that he knew Rockyfeller was not guilty and he also knew that the statement he made was false and that I had been with the CF&I for thirty years and the statement regarding John D Rockyfeller spending ten thousand dollars for booze for getting petitions signed was false[.] I appealed to the men to pay no attention to the IWWs as they were an outlawed organization.

Walsenburg, Colorado

November, 15, 1927

Unlike XX, who reported from within the IWW leadership, X was not interested in the union. His job was trying to convince his colleagues not to join the strike. His speech at this strike meeting in Crested Butte echoed the press’s denunciations of the IWW wherever the union appeared. The fact that the strike leaders who came to this meeting did not readily acknowledge their membership in the IWW indicates that many of the striking miners were not Wobblies, or even sympathetic to their ideology.

As a longtime CF&I employee, X’s support for Rockefeller, the owner of the company, is understandable. The firm likely hired a man with X’s seniority for this task in the hope that respect for his experience would make his case more convincing to wavering strikers. Despite X’s work, Crested Butte’s miners voted to join the strike at this meeting.

“X” REPORTS:

They sent word from Old Mexico to Russian Council to finance money to support Colorado Strike. Word came back to representative of Russian Government that he could use $50,000 at the present time to go ahead with the strike. This money did not go through bank or post office, but was received by committee in Eagle Pass and was personally delivered from there to communists in Denver.

They are getting out a bulletin which is to be sent to all parts of the country and the world to get in touch with all the unions.

Money is coming in pretty fast but is going out just as fast. Thousands of dollars going out every day.

The notion that the Russian government supported the IWW would have appealed greatly to CF&I’s management. Since it was widely assumed that communists posed a threat to the stability of the United States, this would put the company on the front line of the battle for freedom.

However, remember the report of October 12, excerpted above: The idea that a worker who confronts and denounces IWW members at an open meeting would know exactly where their money comes from is hard to believe. This report is interesting because of the attitude it reveals rather than the information it might contain.

On November 21, state policemen killed six pickets and injured dozens more when the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company reopened its Columbine mine in Weld County. The victims, part of a crowd of four or five hundred strikers, were shot while retreating from a barrage of tear-gas bombs. Despite the fact that the violence was the fault of the state police, Governor Adams used the so-called “Columbine Massacre” as an excuse to call out the National Guard to restore order throughout the state. With soldiers on guard at mine gates, mass picketing ceased and more and more miners returned to their jobs. The strike continued, but it lost considerable momentum.

X-3 Reports – Trinidad – Meeting Night December 20th, 1927.

Two delegates last night. One of them was our one eyed delegate whom I understand is the Regular Secretary of the City Local . . . .

The other delegate was an old man. I could not get his name but he came from Walsenburg with the one eyed delegate today. He claims he has belonged to the I.W.W. for 25 years. He is not grey-headed yet but is an old man. I would say about 58 years of age and his face is al [sic] wrinkled. He addressed the crowd with stay with it – stand pat – Don’t give up the fight not until the last man, nor give any cause for arrest, because if you are arrested without a cause they will have nothing against you. He also told the crowd that this woman delegate in Chicago would address another meeting some time next week in order to build the relief committee. He says that this is necessary in order to raise money to feed about 13,000 or more strikers out on strike. He said three fellow workers were touring the Country in order to help the same cause. One fellow worker named Embree [see sidebar] was in Ohio some place. One fellow worker named Kitto was in California and one was in Washington, by name of either Faundy or Founty. This name I could not get right. They are all working for the same cause; to help win the strike.

Here X-3 is describing IWW efforts to use its national organization to help Colorado miners. Despite national publicity, whatever outside help the union brought in was not enough.

By late December, the State Industrial Commission began to collect testimony from striking miners describing their grievances against their employers, especially CF&I. At the same time, and perhaps in response, state and local officials began to accelerate their efforts to break the strike. Most notably, from December 24 to December 27, Trinidad police raided the local IWW hall three times, searching for weapons and arresting its occupants. Faced with this onslaught, support for the strike began to wane.

On December 27 Trinidad’s acting mayor, Dr. James Espey, put out the call for a citizens’ antistrike force, asking volunteers to gather that night for commissioning as “special police officers.” Many signed up and, as historian Charles J. Bayard writes, “On the next day they lashed out at the remaining core of the strikers in Trinidad. The citizen band took more than forty captives and marched them with arms overhead to the jail. The remaining strikers fled from the area . . . .”

Walsenburg, Colorado,

December 30, 1927

“X” REPORTS:Tulin says they must have more action, picketing and fights so will get on first page of news papers, or they will be unable to collect much more money . . . .

X-3 Reports January 1st, 1927.

The news is that twelve men have deserted the Trinidad Local and have scattered around to try and get jobs. There were thirteen cars at the local house yesterday. I heard that some of these had come down from Segundo to clean up on the relief that was down in the Old Local House as they haven’t been able to get relief up there for sometime.

Without food money or monetary relief from the union or other sources, some strikers were compelled to return to work. By the beginning of February, the union was realizing that the strike was lost.

X REPORTS – February 9th, 1928.

Rozanski went to Denver tonight to take up with the Secretary Board in regard to calling the Strike off. The Strike Committee of all districts in the Southern Field are to meet tomorrow and make arrangements to see whether or not they should call the strike off. Conrado Avillar [see sidebar] was here today with a note from Svanum, which was written in the jail and [a] copy of which was made on typewriter by Avillar, saying he could not see anything but to call the Strike off, but he wanted the organization kept up. Says if the men get back to work, they can organize, and that he himself will be around and they will have organization here, so that by next fall they will be well enough organized and be in shape financially to close the mines in Colorado down tight. The rank and file are expecting this as a number of them have made remarks that the strike was going to be called off and they will be left the goats, and then none of them will be able to get jobs. Who ever has to tell them that the strike is called off may not look the same after he gets through telling them, although they do want to get back to work and most of them are getting mighty hungry.

Despite falling support, this report indicates that many strikers in Crested Butte (where X worked) wanted to continue the walkout. Nevertheless, ongoing defections and increasing hunger among the strikers took their toll.

“X” Reports – February 10, 1928.

The Strike Committee met today, Conrado Avillar was elected Chairman and Frank Anaya Secretary, Shepherd saying he could not be there on account of his wife being sick, but the whole Strike Committee agreed that it was because he did not want to be there.

Meeting was called to order and discussion started on what should be done with the Strike. Everyone there was in favor of a plan whereby they might call the Strike off, if relief could not be had. Tomas Garcia opposed it and said they were all crooks and traitors or words to that effect, and finally Garcia was ordered out of the room and told that he had no business there in the first place as he was not a member of the Strike Committee. The whole Strike Committee is sore at Garcia for the stand he has taken, and after Garcia left it was decided that the Secretary should write to the State Executive Committee and ask them to send somebody hear [sic] to hold a convention, when things could be brought to a show-down, and asked that this convention be held as soon as possible, that the rank and file was very uneasy.

Aguillar [sic], Trinidad and Valdez are in very bad shape for relief. A committee from there today said that something had to be done at once, that the rank and file were breaking, that fifteen or twenty at the Aguillar Branch had gone out looking for work. The Trinidad soup kitchen had no coffee this morning. They got a little money from Shepherd to buy coffee with. Also took two sacks of potatoes from the Walsenburg Kitchen . . . .

Another reason the strike ended was workers’ fears that they would be unable to get their jobs back. As one miner told the Colorado Labor Advocate on January 26, “Try and get a job in any mine now. They’ll tell you they have full shifts and they have. They’re getting ready to lay off men—they have so many. Operators are filling all orders. We’re not striking because there ain’t no strike!”

On February 7, miners at Aguilar, Trinidad, and Valdez voted to return to work, pending the report of the state Industrial Commission. Other miners soon followed.

X Report Feb. 18, 1928.

Word was received from the Committee in Denver that a vote had been taken in Fremont County to go back to work pending a decision of the Industrial Commission, and that not wanting Fremont County to go back ahead of the rest, they sent ballots to the Southern fields today and the vote will be taken on it Tomorrow Sunday at eight o’clock. The rank and file have already had orders to go out Monday morning and secure jobs, but Epstein says for everyone to try and get a job at CF&I mines, and if they can’t get work that they will take it up with the Industrial Commission.

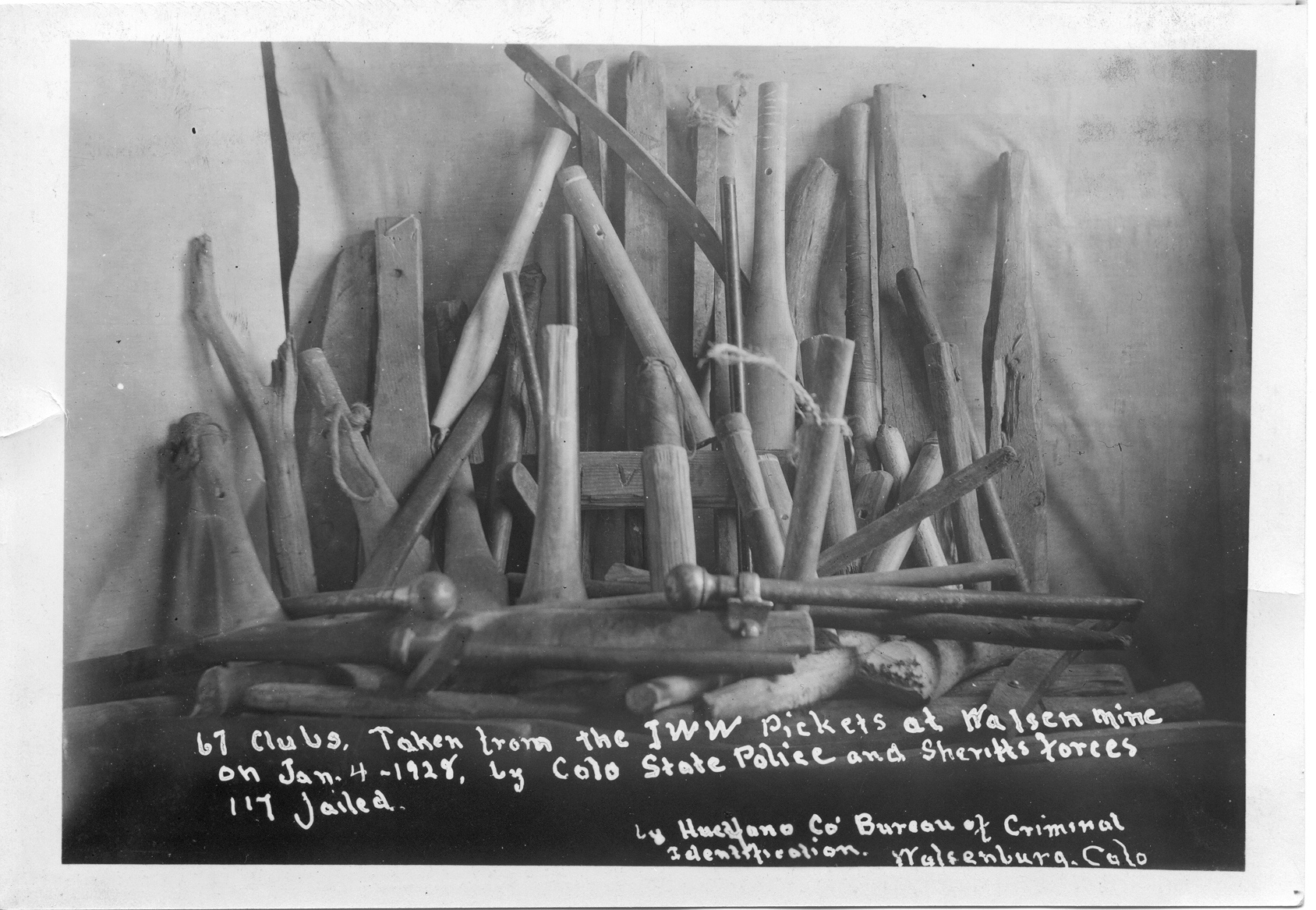

Clubs and sundry weaponry were seized from the more than one hundred picketers arrested at the Walsen mine in January 1928, in the final days of the strike.

The strike ended on February 22, 1928, with each local technically suspending the strike (rather than officially ending it) in anticipation of the state Industrial Commission report. The IWW took credit for two wage increases—one implemented before the strike and the other during—that originated with CF&I and spread throughout the Colorado fields. However, most of the Wobblies’ pre-strike demands were not addressed. The state Industrial Commission delivered its report on the strike on March 20. The commission was surprisingly sympathetic to the miners’ cause, concluding that many of their demands were justified and that “some system of collective bargaining should be used.” The IWW continued to try to organize miners after the strike ended, and CF&I’s labor spies continued to report on the union’s activities.

X Report Feb. 25, 1928.

Things have been very quiet at the hall the last two days. Leaders say things will be quiet until the first of the month at which time the State Police will be taken off, and they will have free rein and be able to do as they please around the District.

The Strike Committee decided today that there would be only two meetings held a week aside from one business meeting. The soup kitchen will be closed tomorrow night. There is notice posted in the kitchen to this effect . . . .

. . . A letter from Tuling advising everyone to get ready to strike again in the near future. He said to make each member a organizer and asked that each member get at least one scab to join the Wobblies, and if they did this they could call another strike at once.

The IWW never had a chance to strike Colorado’s mines again. Days after the Colorado Industrial Commission’s report denounced the industry for not providing adequate collective bargaining, the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company issued a statement expressing its willingness to sign a contract with the United Mine Workers. A conservative mainstream trade union, that company reasoned, was a better bargaining partner than the Wobblies. The contract with Rocky Mountain Fuel Company encouraged the UMW to organize at other firms across the state, including CF&I.

With the help of the National Labor Board, a government agency created by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act, CF&I’s miners voted to abandon the company union that had been in place since the aftermath of the Ludlow Massacre and join the UMW in 1933. Shortly after that vote, the company signed a contract with the union. The United Mine Workers reaped what the Wobblies had sown.

For Further Reading

The reports excerpted in this article come from records in the Colorado Fuel & Iron Archives in Pueblo. Because these records are inventoried, they are open to researchers under the terms of Steelworks Center of the West’s access policy. Because they are also unprocessed, exact box and folder numbers are unavailable.

Overviews of the 1927–28 strike can be found in Donald J. McClurg, “The Colorado Coal Strike of 1927,” Labor History 4 (winter 1963), 68–92, and Charles J. Bayard, “The 1927–1928 Colorado Coal Strike,” Pacific Historical Review 32 (August 1963), 235–50. The author relied heavily on McClurg, “Labor Organization in the Coal Mines of Colorado, 1878–1933” (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, 1959), and John Thomas Hogle, “The Rockefeller Plan: Workers, Managers and the Struggle over Unionism in Colorado Fuel and Iron, 1915–1942” (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Colorado–Boulder, 1992). See also John R. Salter, “Embree, A. S.,” Encyclopedia of the American Left, Second Edition, Mari Jo Buhle, Paul Buhle, and Dan Georgakas, eds. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998): 207–8.

The author thanks Rocky Mountain Steel Mills, previous owner of the material excerpted in this article, for allowing him access to it. Thanks also to the Steelworks Center of the West, Janet Boyd, Janelle Abeyta, Adam Hendren, and Crystal Wold.