Story

The Dirt Was Everywhere

Remembrances of a Childhood on Colorado's Eastern Plains

As told to J. Joseph Marr

Joseph P. Weibel was born at the beginning of the 1930s on Colorado’s eastern prairies, with the dust and grasshopper storms, drought, and the Great Depression. His family endured privation that is difficult to comprehend in the twenty-first century. That time—and its terrible hardships—stayed with people, like Joe, for their entire lives. Joe and I have known each other for over fifteen years and have spoken much about that time. Now ninety years old, he agreed to tell me his full story of those terrible days in a series of interviews, sharing how it was for him then in hopes that it would help others appreciate it now. The words presented here are his, rearranged and edited for clarity and sequence.

My dad, Louis Weibel, and mom, Margaret Bracktinbach Weibel, had a farm with 160 acres in eastern Colorado, about eight miles north of Stratton, near the Kansas border. When Dad and Mom got married his father gave them 80 acres, with only the down payment made. Dad wanted to be a builder, he never wanted to be a farmer.

I was born March 6, 1931, at Grandmother Bracktinbach’s house. There was a blizzard raging and a neighbor came to help Grandma. Granddad and my dad were on the way to Stratton to get the doctor. By the time the doctor got back to Grandma’s house, I was lying next to Mom and screaming. I was their third child. Their first, Justin, lived only six months and died of the “dirt pneumonia.” I had a brother, Andy, about two years older.

Our house was one story, with no insulation, no electricity, and no plumbing. It had a wood floor, but it wasn’t very good. The water was outside; you had to go to the windmill and carry back a bucket. There was no toilet in the house, so you had to run out in the cold or heat and then use [a page from] the Montgomery Ward or J.C. Penney catalog. I never heard of toilet paper. The house had three rooms: a kitchen, a bedroom, and another room where Andy and I lived along with things in storage. The only heat in the house was from the cooking stove, so we wore whatever clothes we had to stay warm. In cold weather, we heated rocks in the stove to put in the beds.

There was no icebox, but my grandmother had a pit dug at her house, with straw in the bottom. In the winter, it filled with snow and run- off water and froze. We cut ice from the pit with a saw and used horses to drag it to our house, where we put it into another pit. This was the icebox until the spring thaw. We kept root vegetables and meat that we butchered in there. Every other Saturday, the county gave away food and clothing and we were there for it.

The dust storms that began in the early 1930s were a great environmental disaster. The drought of 1888 to 1889 caused more economic damage, but it did not hold the terror and despair of the dust storms. During the Dust Bowl, more than 100 million acres of land turned into dust and the resulting clouds went up 10,000 feet in the air. For people living on the Plains, like Joe’s family, there was no warning since there was no communication. The dust permeated everything and everyone. It covered homes and fences—and both disappeared under the shifting, abrasive particles that scoured paint from homes and skin from the face. Children and adults sickened and died from “dust pneumonia.”

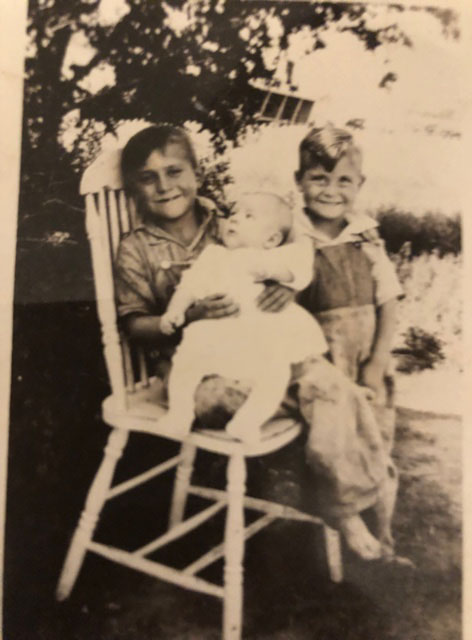

A six-year-old Joe, in 1937, holds his new brother Don, and Ken stands to the right of the chair.

My first memory of the dust storms was Mother and Dad getting quilts wet and nailing them over the windows and doors so that when the dirt came, we would not die from it. The dirt was everywhere and went into every part of our house. I remember neighbor who covered every opening to his house except the keyhole, and afterward he had about three inches of dirt in his house; it all came through the keyhole.

The dust storms came for years, and covered fences, houses, barns, and anyone left outside was buried and died. Sometimes the dust storms made static electricity. It would affect the vehicles and they would just stop. Every car dragged a chain along the road to ground the car so it wouldn’t stop running.

We had a rope tied from the house to the barn. We would hold on to it during the dust and snowstorms when we went to milk the cows. We wore masks and bandanas over our faces, and you couldn’t see anything. If you lost hold of the rope, you were lost. The dirt was in everything.

I think about 50 percent of the people left. They put everything in a truck and started to California or Oregon. Some of them stopped wherever they could get work, but most went all the way. They had a much better life out there, I think. I don’t know why some of us stayed, we had nothing—not even hope.

He stopped talking for a moment, his face hardened, and he stared past me. He had gone back there. He trembled, and looked lost, and then shook his head and looked at me.

You know...the worst thing was that we didn’t know if it would ever stop.

He paused again, stared back down at the table, shook his head, and became silent. Sometime later, he continued.

When I was about four, I remember Dad came in at lunch after plowing the field with two horses and a two-blade plow. He said, “If it’s like this next year, we’ll lose the farm and I won’t care.”

Dad planted rows of corn in the spring. One summer, because of the winter snows, the corn was three or four inches high. Then a cloud of grasshoppers that blocked out the sun flew in and ate the crop—every stalk—down to the dirt. I remember Mother and Dad standing over the field, crying. Yet the wind and dust never stopped, and the rain never came. But the bank came and foreclosed on the note.

In 1935, Mother, Dad, Andy, and I left the farm in a one-ton truck with only one seat. Mother started crying and said “What are we gonna do? We have nothing, we have no money. What are we gonna do?” Dad said, “It can’t be any worse to move to town. We will make it.” Everything Dad and Mom owned was in the back of the truck. Tied to the back of the truck was our milk cow. We drove down the dirt road toward town and closed out one part of our lives. We didn’t know what the next part would be, but Dad was right, it couldn’t be worse.

The Depression, dust storms, drought, and grasshoppers that finally ruined the farm were not an unusual story on the Colorado plains, in the Texas Panhandle, Oklahoma, or Kansas. It was a subsistence existence dependent on nature and luck, and both seemed to be against farmers at the time. There were no thoughts of the future, only surviving the present. Life for Joe and his family continued in Stratton, population of 300, but so did the dust and grasshopper storms and the crushing economics of the Depression. The only improvement about living in town was that the grasshoppers were eating someone else’s crops.

The house we moved into was the cheapest thing Dad could find, and we lived there about ten years. It was on a dirt road—they were all dirt—and it had a kitchen, two bedrooms, and a porch on each end. There was no indoor plumbing, but we had a spigot for water right off the porch, which would freeze in winter if it was not drained each time we used it to get a bucket of water.

Since we still had a milk cow, we had fresh milk, cream, and we made our own butter. There was a chicken coop in the yard and that two-holer outhouse (with a Montgomery Ward catalog inside). I remember the rats living down the hole. Dad would shoot them, and more would move in.

Everyone was out of work unless they worked at one of the stores, or still had a farm, or was a doctor. The government started a work program and Dad went to work making out-houses for the three Cs [Civilian Conservation Corps], who built roadside parks along the highways that no one used. He also worked for them in grass fields, cutting cactus and soaproot. I think he made about two dollars a day.

Mother and Dad bought 200 baby chicks from Denver each year, which were delivered by the railroad. We had to be at the train for the delivery or they would die or disappear. When I was about five or six, one morning Andy came running into the house yelling that there were rats in the chicken coop. They wanted chicken dinner! Dad said, “We gotta fix that!” He got some wire netting from the junkyard, and Andy and I dug down six to ten inches to install the wire netting. That kept the rats out.

Since we didn’t have land to plant a crop, we went to Grandma Bracktinbach’s farm, about six miles out of town, and planted potatoes. It was done on Good Friday each year, after church. Potatoes were cut up and shoved into the ground by stepping on them and then kicking dirt over them. We took care of the crop all summer and in the fall harvested the potatoes. Grandma kept some and we put ours in the root cellar for the winter. The dirt cellar was really dark and filled with spiders.

We lived right across the alley from the grocery store on Main Street. Next door to the grocery, there was a hardware store where I worked some years later. One time I found a coin that looked like a silver dollar, so I went to the grocery store and bought candy for myself, and bread, and beans, and oatmeal. It added up to a dollar. Looking back, I don’t think it was an American dollar, but the grocer took it.

It was a tough life in town, too. Every other Saturday we still went to the county garage and got some food and clothes, and we were damn grateful. We did everything to survive. My brothers and I trapped skunks and badgers and shot rabbits and pheasants for dinner. We ate what we shot and that was it. If we didn’t shoot something, then there was no dinner.

We did something else to survive that involved the whole town, and it will show you just how hard it was to live out there. There were lots of jackrabbits on the prairie; you could see them jumping around in the brush. In the spring, when the crops and garden vegetables began to grow, the rabbits would eat everything that came up. So, we had jackrabbit drives. We took snow fencing outside of town and set up a U-shaped trap—about the size of a football field—with one side open. There were fifty to a hundred people involved.

Then, the kids and people with dogs would spread out in a line that covered about half a section (about a half square mile) and we would drive the rabbits toward the fence. When they were inside, the fence was closed around them. There were several hundred of them in the trap. All the kids had baseball bats and we went inside and began to hit the rabbits. When all the rabbits were dead, we skinned them, and sold the skins for about twenty-five cents per hide. We gutted the carcasses and kept the meat. The pigs got all the rest.

Dad and us boys built a bathroom on one side of the house. We really enjoyed having this because we still had to heat the water on the stove, but we didn’t have to sit in a small tub on the kitchen floor to have our baths. At that time there was no sewer system in Stratton, so Dad said, “You boys are going to dig a cesspool.” The cesspool was about fourteen to eighteen feet deep and four feet wide.

We used a homemade winch and hand-crank pulley system to bring up the dirt. The person not digging had to dump the dirt and send the bucket back down to the digger. The digger had to go down the hole in the bucket. We all took turns. About fourteen feet down there was a foot and a half of sandbar. The drained water went into the sand and went...someplace. All the water in the house drained into it.

The constant scramble for money dominated this era. Children in their early years assumed the work responsibility of adults. Entry into school was a temporary escape that made them aware there was a world outside the Dust Bowl. It also provided sorely needed intellectual stimulus and psychological respite from the soul-deadening pressures of continual privation.

I went to the St. Charles of Borromeo Catholic School. My older brother was in fourth grade, and then I started. Each morning we would bring in a tub of water and mother would be sure our ears and faces were clean. Walking to school and home in the dirt storm was a bastard. We wore a piece of cloth for a mask and you barely could see through it. Nobody ever smiled, except when there was good weather. Then they would smile at you and say, “How’s it going? All right?” And we would answer, “All right!” But it never was.

I don’t remember much of the first school years, except, since we went to daily Mass, we ate our breakfast at school. My brother and I packed breakfast and lunch in a half-gallon syrup can (it looked a lot like a two-quart paint can). Breakfast and lunch were the same: bread and a fried egg. After we ate, we lined up at the drinking fountain for water. We paid for school with milk and cream from our cows, eggs from the chickens, and sometimes the chickens too. Anyway, I got a pretty good eight years of education there.

The school was run by nuns, and some of the nuns would slap you upside the head or hit you with that sharp edge of a ruler if you did not behave. The school had no indoor plumbing and no cafeteria. The girls had a three-holer and the boys had a two-holer. The boys had two tin troughs (metal tubes cut in half) in the outhouse for a urinal.

We had three classrooms. One room was grades first through fourth, the second room was fifth to eighth, and the third was the music—church music and Christmas music—and art room. There was no physical education, but we did have a fifteen-minute recess outside without any playground equipment. We made our own games. In the winter when it was cold, we brought water from home to put on the sloped sidewalk to freeze, so we had an upright sliding contest.

Dad finally got on with the power company and worked from 4 p.m. to midnight servicing diesel engines. That brought in some money and we bought another house just outside of Stratton. It had three bedrooms, a kitchen, and a porch but, this time, electricity and indoor plumbing. We still needed to expand, so Dad bought a deserted barn and we tore it down. We saved the lumber and straightened all the nails and built two bedrooms.

Life never really got easy. We had two cows now. They lived in the yard, and my brother and I had to take them out of town to a field so they could get some green in their systems. We took them out in the morning and staked them and brought them back in the afternoon. They were wet and muddy, and their tails would be covered in manure which would dry into a hard knot. We had to milk them when we brought them back and, while we did it, they would swing their tails around and hit you in the head with that knot of manure. I hated those cows!

I graduated from Stratton High School in 1949 and went to college at Colorado A&M in Fort Collins [now Colorado State University]. After one semester I realized I wasn’t ready for college and went back to a job I had at the Stratton hardware store. I really wanted to get out of Stratton and looked for anything that would take me away. Finally, I went to work for the Highline Electric Association. We took electricity to rural America. I helped build the power grid one pole at a time in Kansas, New Mexico, and Colorado. But when I was between jobs, I was back home again in Stratton. It seemed I could never shake the place where there were dust and grasshopper storms, the Depression, death of a brother, and poverty that kept me looking for money every day.

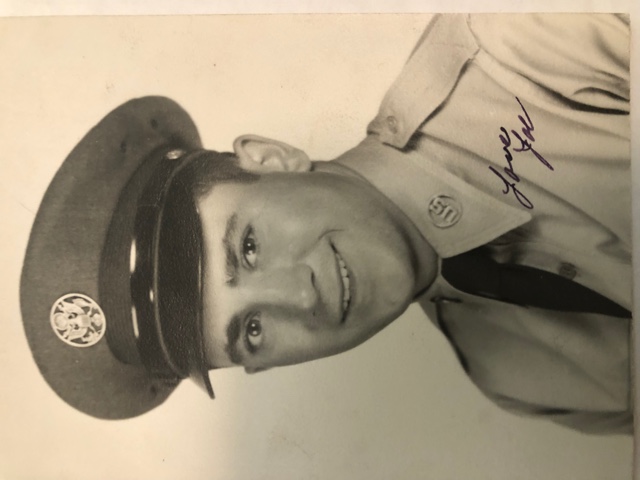

In April, 1951, the Korean War and a bus finally took Joe out of Stratton. He learned from a girlfriend, whose mother worked at the draft board, that he would be drafted soon, so he and a friend took a bus from Burlington to Denver and enlisted in the Air Force. He was sent to Tokyo, Japan, and began a new life. After thirty months, he returned to northern Colorado and worked selling oil field equipment for the next thirty-seven years. He and his wife, Dee, (who grew up near Stratton under similar circumstances) were married for fifty-five years and raised six children. Although successful in his life and work, his early years never left him.

Joe designed and built a house near Casper, Wyoming in 1980. It was a masterpiece of engineering and use of renewable energy at a time when that almost was unheard of. The house was set ten feet down into the side of a hill overlooking the North Platte River—and hidden from wind. The portion below ground kept the home at a relatively constant temperature year-round and a large solar panel provided heat. One small room was devoted to a pump and water supply from their well. The top level of the house and the garage were above ground, with a third of the garage given to a heat management system that used the solar heat to supplement a heat pump. The home was a triumph over the adversity of his early years and a reward for hard work and patience. But the memories of those years on the High Plains hovered just below the surface of his mind to emerge at unpredictable moments. Ninety years later, he has not been able to put aside the dust, drought, depression, and death on the eastern Colorado plains of his childhood.