Story

Winning Spirit

Each year, the Miles and Bancroft Awards highlight exceptional historical projects in Colorado. Here’s what last year’s winners have been up to.

What makes a year eventful? Challenges overcome? Accomplishments made? For cultural heritage institutions across Colorado, the answer is likely a little of both—and then some. The annual Miles and Bancroft Awards presented by History Colorado recognize a few of the most eventful historical projects across the state. Named for former Colorado Historical Society Volunteer President Josephine Miles and local Colorado historian Caroline Bancroft, the awards gift up to $1,000 to winning projects. As applications open for 2022 and the June 1 deadline approaches, we thought it was time to read about last year’s winners for a little inspiration about the innovations Colorado institutions have made in telling our state’s history.

Creating the Racism at the Lafayette Swimming Pool - 1934 exhibit at The Collective Community Arts Center in Lafayette

How They Did It: While museums and organizations large and small dealt with several challenges stemming from the ongoing pandemic, it was far from the only matter driving change and adaptability in how history is told. The murder of George Floyd in police custody in May 2020 turned much of the nation once again toward issues of race in America. Many cultural heritage institutions have been actively seeking ways to further collecting, exhibition, and community engagement in a way that includes historically marginalized groups, a goal that has only become more urgent over the past year and a half.

The Arts and Cultural Resources Department of the City of Lafayette discovered its own need to tell more diverse stories in history as early as 2017. In preparation for an exhibit hosted by the University of Colorado Center for Ethnic Studies and Boulder County Latino History Project, the Lafayette Historical Society learned that their collections sorely lacked material relating to the local Latino community. With the extensive help of local historian and longtime Lafayette resident Frank Archuleta, the City of Lafayette developed its own exhibit, Latinos of Lafayette Photo Exhibit that traveled to several different sites around the city in 2019.

While gathering photographs for the exhibit, Frank heard and collected stories from Lafayette’s Latino community that dated back several decades. One particular story about the local swimming pool, that took place in 1934, stood out as an open secret among many residents—one with great importance both then and today.

In 1933, Lafayette began construction on its first public swimming pool with funding and assistance from the community. Contributors to the pool’s construction included many members of Lafayette’s Latino community, who had settled in the area to work as coal miners, ranchers, and farmers—making up around 20 percent of the community’s total population. Like much of Colorado in the preceding 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan was also prominent in Lafayette. With them, prevailing racism was directed at non-white and Catholic communities.

By the early 1930s, white supremacy and Klan influence still thrived in the area, which became evident by the time the pool finally opened in 1934. Despite involvement from multiple Latino families in donating money and resources, they were ultimately barred from using the pool. The Lafayette Volunteer Fire Department, to whom the mayor and city council had leased the pool to make it privately owned, placed a “White Trade Only” sign outside its entrance shortly after opening.

Refusing to have their Fourteenth Amendment rights denied, Lafayette’s Latino community challenged the ban in 1934. The effort, which included twenty-six Latino families, was led by Rose Lueras, a thirty-four-year-old mother (she and her husband, Santiago, had donated ten bags of cement for the pool's construction). They sued the City of Lafayette in Boulder District Court on August 13, 1934, prompting the city to close the pool shortly after the case was filed.

The city’s attorneys actively filed motions to have the case dismissed, which dragged it out into 1935. Meanwhile, Lueras and her family were subjected to intimidation by the local Ku Klux Klan chapter. A burning cross appeared on their front lawn at 304 East Chester Street, which led Lueras to leave Lafayette for Santa Monica, California, with her thirteen-year-old daughter, Rosabelle.

A descendant of Rose Lueras poses by a panel in the Racism at the Lafayette Swimming Pool–1934 exhibit at The Collective. The pool at Lafayette’s Bob L. Burger Recreation Center, which is not far from the city pool where Rose and other Latinos were barred from entering, was officially renamed the Rose Lueras Pool on December 17, 2020.

Tragically, Lueras passed away before she could formally appear in court to make her case. (While staying in Santa Monica, she was fatally struck by a car while crossing the street.) Although the other plaintiffs moved forward with the case, the defense tried to dismiss it altogether since the lead plaintiff had died.

The case was allowed to move forward, and Lueras’s daughter, Rosabelle, testfied on her mother’s behalf along with eight other Latino plaintiffs. Rosabelle recalled the day she and her mother arrived at the newly opened pool, as well as the fire department’s stated reason for turning them away: “We don’t allow the Spanish American or Mexicans to go in to swim.” Firefighters and city officials were also questioned by lawyers, admitting a perceived need to “keep all disputes down,” a statement that referred to the barring of Latino residents. In spite of all this, the plaintiffs still lost the case. An appeal to the Colorado Supreme Court also ended with the court siding with the City of Lafayette.

Lafayette closed the pool and filled it with dirt shortly after the case concluded, effectively burying the story of Lueras and others who challenged the ban. However, Lafayette’s Latino community kept the story alive themselves, preserving to memory what was omitted from the formal history of the city. While the story long remained hidden from broader public view, Frank Archuleta and the Lafayette Arts and Cultural Resources Department saw an opportunity to finally bring Lueras’s story into the limelight.

The City of Lafayette and its partners, including the University of Colorado Center for Community Engagement, Boulder County Latino History Project, Lafayette Historical Society, and several members of Lafayette’s Latino community whose families had experienced the pool ban, joined together to create an unprecedented research initiative on Rose Lueras and the efforts she led. The end result was the outstanding Racism at the Lafayette Swimming Pool–1934 exhibit, which opened at The Collective Community Arts Center in September 2020. As Susan Booker, the Cultural Resources Department Director, recalls, “having this exhibit allowed us to make relationships happen that we might have worked for years to engage.”

The process of developing the exhibit was insightful and groundbreaking in the way it uncovered a lesser known story, but it was not without its challenges. Exhibit leads had to be mindful of past trauma in the ways that Lafayette’s history was told, and of how Lueras’s story was buried for so long. “Building relationships and gaining trust is not a one-and-done thing,” says program manager Rachael Hanson. “This is an ongoing, long term, continuous…process of showing up and doing what you say you’re going to do…listening and having really hard conversations sometimes, and feeling great rewards sometimes, and feeling real sadness sometimes.”

In the early stages of exhibit planning, Lafayette’s city council and the Lafayette Human Rights Commission held a dedication and ceremony to officially name the current community pool the Rose Lueras Pool on December 19, 2019. Living descendants of Lueras and other plaintiffs attended, standing close to the very site where their families had been banned eighty-five years prior. The exhibit expanded on this symbolic milestone by telling the story behind the pool, informing all Lafayette residents of the amazing courage involved in challenging the city’s racism and prejudice. “Hopefully, it does inspire other communities to take a look inside and not be fearful to tell the hard stories,” Rachael Hanson says. “Hard stories are scary and they’re sad, they generate a lot of feelings that are unpleasant, whether fear or upsetting feelings…but that’s important work, and it’s important to face that head on so that you can grow and heal and start the process of repairing damage that you may not even know is there.”

Digitizing and transcribing the Alfred Borah Journals with Eagle County Historical Society and Eagle Valley Library District

How They Did It: History projects can come in all different sizes, but even seemingly small initiatives can have a large impact. Eagle County Historical Society and Eagle Valley Library District proved this point with their digitization and transcription of the Alfred Borah Journals, an invaluable resource for the county and the state at large.

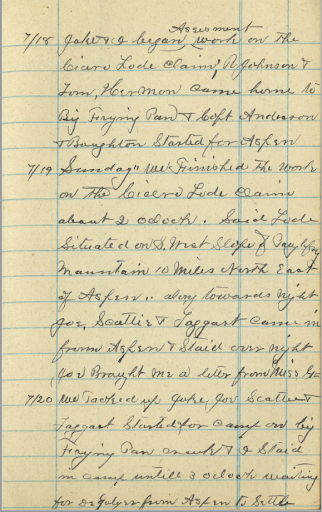

Alfred Borah and his brother Jake lived as homesteaders throughout many different areas of the state starting in 1882. They traveled constantly between Leadville, Meeker, Aspen, and Eagle, all while working as hunting guides, miners, ranchers, and businessmen. Alfred took meticulous notes of their ventures in his journal, which has survived to the present, 117 years after his last entry in 1905. “They went all over the Western Slope,” recalls local historian and president of the Eagle Historical Society Kathy Heicher. “The value of this archival item goes well beyond Eagle County….It reveals stuff we didn’t have records of before.”

Alfred eventually moved to Arizona in the early 1900s after sustaining an injury from a landslide, and the cooler mountain weather only exacerbated what may have been arthritis. The journals made their way back to Eagle County in 2017 after Kathy McDaniel, a descendant of Alfred Borah, donated them to the Historical Society. The Society worked closely with the Eagle Valley Library District, which maintains a history librarian position to manage their special collections archive, to determine the best way to preserve the journals and make them accessible in the long term. Grants from the Colorado Historic Records Advisory Board (CHRAB) and the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) helped fund the purchase of a book scanner to facilitate the journals’ fragile bindings. By early 2020, all eight journals were scanned with the help of the library’s team of volunteers.

A sample page from the Alfred Borah Journals, which were scanned and transcribed last year. It details some of Alfred’s mining work ten miles northeast of Aspen and other areas of a claim to offer a valuable firsthand account of homesteading life in Colorado.

The next logical step in the project was to transcribe what staff refer to as the “spidery” handwriting of the journals so it was more readable for researchers. However, the onset of the pandemic changed many of their original plans. Matthew Mickelson, the current History Librarian, transcribed 900 of the journals’ 1,200 total pages over the next year after the pandemic lockdown limited volunteer help at the library. “It was a very tedious process, but well worth it,” Mickelson says. “Just being able to have first-hand accounts of a lot of the stories in the county that we know have been passed down through generations...is such a great resource to have.”

Now that the journals are transcribed and available to the public (a process that was sped up as much as two years because of the lockdown), previously unrecorded events in the journals provide invaluable insight for historians of the Western Slope, including Kathy Heicher. She and Mickelson have found confirmation of events previously mentioned only briefly in local papers in and around Eagle, or consigned to oral accounts passed down generations. Even major historical figures are mentioned, bringing Eagle to the forefront of Colorado history. For example, the journals provide additional information about Chief Colorow and many Ute people continuing to trade in Colorado, their ancestral homeland, after the Ute Indian Tribe, also known as the Northern Ute, was forced from the state in the 1880s; Alfred himself traded directly with Colorow. Jake Borah was also known to have entertained Teddy Roosevelt, utilizing both his hunting expertise and social skills while Alfred took care of business in the background.

Even passing, personal stories of Alfred Borah’s life paint a detailed picture of how he and others lived around Eagle. Heicher’s favorite account is of a business trip Alfred took to Glenwood Springs, which required an express trip by train with no stops. Alfred had already bought an engagement ring in Leadville for his future second wife, and was excited to propose as soon as possible. Unable to wait any longer, he arranged for his soon-to-be fiancée to wait by the rail tracks on the train’s route, so he could literally toss the ring to her in a box from his moving train car. Personal stories like these demonstrate the human quality of a primary source, which helps people better relate to their local history. As Heicher puts it, “When people know their history, they connect to their community better.”

Both Eagle Valley Library District and the Eagle Historical Society have plans to utilize the journals even more in the future. Mickelson hopes to utilize new exhibit space at the library to better display the journals and the stories of the Borah family, while the Historical Society is already incorporating revelations from the journals into hiking tours with Eagle County Open Space to better tell the history of the county. All of the digitized journals and their transcriptions are available online through the Eagle Valley Library District’s catalog. Kathy McDaniel and other descendants of Alfred had the chance to visit other Borah family members still in Eagle to appreciate the journals over venison burgers, bringing Alfred’s journeys and his writings documenting them full circle.

Exhibits, school programs, and events at the Broomfield Veterans Museum

How They Did It: The Broomfield Veterans Museum was founded by a group of six World War II veterans in 2002 to preserve their stories of military service for the public. It first opened in an old building that used to house the local library, and has operated since thanks to a board of volunteers with assistance from the City and County of Broomfield. The first exhibit cases were constructed in a woodshop by founding board members, and there was just one room for exhibits.

The original group has expanded to a total of thirty-one active volunteers, including board members and twelve docents, as well as a curator in conjunction with Broomfield. The exhibit space has expanded into multiple rooms that occupy the museum’s lower level, each representing a different time period from the Civil War to the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Broomfield’s museum coordinator David Allison, who oversees many of the city’s local museum operations, describes the museum today as a focal point for Colorado’s veteran community and their stories, a “gathering place for individuals who have fought in war—kind of comrades in arms—so that those veterans are able to share those stories in a place where they know that people will listen to them and also be able to empathize with what they have been through and what they’ve done in their lives.”

While the Broomfield Veterans Museum has come a long way in building itself up, it has still faced several challenges over the years. The importance of preserving past veterans’ stories has become more urgent, as many World War II veterans are passing away (including two long-standing board members since 2020). Changes in technology and online communication have also warranted new considerations in how to engage younger visitors and schools, while still catering directly to veterans and their families. Many of these challenges have only been amplified during the pandemic and ensuing lockdowns. “Us growing up, literally every...family had someone who served,” recalls past board president Mike Fellows. “We’re kind of losing that connection. But that to me just means it’s more important to preserve the stories of those who did serve.”

The crowd at the Veterans Day Memorial program at the Broomfield Veterans Museum on November 11, 2020. Many of the attendees are shown wearing masks and distancing as the flag is raised.

Board member David Jamiel, a retired park ranger, avid historical reenactor, and veteran of the Vietnam War, made a significant impact in tackling many of the museum’s greatest challenges. His experience in the National Park Service gave him a perspective suited to a leadership role in a historical museum. He was a frequent speaker for the museum’s “coffee talks,” designed to let veterans speak directly with the community about their knowledge and experiences, and made great strides toward improving the museum’s educational initiatives through the development of teaching kits resembling soldiers’ footlockers. All of these initiatives, on top of day-to-day help with museum duties, made Jamiel an integral part of the museum’s team of dedicated volunteers.

Sadly, Jamiel passed away in February 2021 after contracting Covid-19. In spite of this great loss, the spirit of his work extended well into the year. The museum successfully opened two new exhibits. One is a recreation of a 1960s fallout shelter, which represents Coloradans’ fears of nuclear warfare at the height of the Cold War. Another case exhibit highlights the life of Admiral Arleigh Burke, in conjunction with the Admiral Arleigh Burke Chapter of the Military Officers Association of America in Boulder.

A Colorado native, Burke was highly decorated for his service in both World War II and the Korean War, and served as the Chief of Naval Operations starting in 1955. An entire class of Navy destroyer eventually adopted his name. Lew Roman, President of the Veterans Museum and current head of its exhibit committee, describes the latter exhibit as a good way to expand the museum’s reach outside of Colorado. “The [Admiral Arleigh Burke] Chapter even brought in two military officers from [Washington] DC,” Roman says, “and I think this is pretty good, bringing people from out-of-state to see this exhibit.”

The museum was also involved in several educational initiatives in the past year. In 2020, museum staff and volunteers developed a self-guided tour booklet for seventh- to twelfth-grade students. The guide instructs school groups to split into teams to read labels, examine artifacts, and ask questions of docents to fill out a booklet and earn an American flag lapel pin souvenir to take home.

In early 2021, a social studies and sciences history night at Prospect Ridge Academy saw 125 students partake in a variety of interactive displays on Colorado military history. Replicas of uniforms and equipment from different wars where Coloradans fought were available for students to see and try on. Another display focused on the role women played in western forts from the 1840s to the 1890s, and used historic children’s games to show how soldiers’ families lived on the Western Plains. Board member and military historian Flint Whitlock sees the museum as having an “adjunct” role with Broomfield’s public schools through these initiatives, “where individual students and their families or classes of students can come and tour the museum and gain a broader perspective of the military service that Americans, and specifically Coloradans, have devoted to the defense of their country.”

Much of the Broomfield Veterans Museum’s progress during a tough year culminated in two major events, each showing great strides in overcoming the challenges posed by the pandemic. A Women’s View of World War II featured reenactment performances depicting Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz, a French freedom fighter during the war, and an American woman speaking on the importance of correspondence with serving soldiers. With the success of these events and other initiatives, the Broomfield Veterans Museum is on track to continue much of the great work started by David Jamiel and the rest of the museum’s team of dedicated volunteers. As 2022 rolls out, the museum has even more exhibits, programs, and events to keep Colorado veterans’ stories alive for all to appreciate.

Attendees of a history hike at Trail Gulch and Brush Creek in July 2020. These outdoor history tours are offered by Eagle County Historical Society and incorporate insights from the digitized Alfred Borah Journals to tell detailed stories of his travels and Eagle County history.

Now It's Your Turn

Are you or your organization working on a historical project? Do you know local historians or other institutions who deserve recognition? You’re in luck, because applications are now open for the 2022 Miles and Bancroft Awards!

Both awards, which offer up to $1,000 for the best project, celebrate individuals, organizations, or museums in Colorado that have made a major contribution during the year to the advancement of Colorado history. Visit the Miles and Bancroft Awards website for details and information on how to apply.