Story

Race to the Clouds

For the 100th Running of the Broadmoor Pikes Peak International Hill Climb, we take a closer look at the famous road race’s history.

On a late summer day in 1922, the sun peeks through towering trees at the base of Pikes Peak. The breeze is chilly and gray cumulus clouds tease nearby. With luck, the dry weather will hold out just a bit longer. The smells of gasoline and pine mix in the air as a bright yellow vehicle rumbles, raring to run like a stocky mechanized racehorse and chomping at the bit to GO! With the wave of the green flag, the Yellow Devil is ready to use its frenetic horsepower to break away from the starting line.

Spencer Penrose’s 1918 Broadmoor Special, nicknamed the “Yellow Devil,” on display in downtown Colorado Springs, 1926.

Today, the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb (PPIHC) is as riveting as it was in its infancy, when Spencer "Speck" Penrose's Pierce-Arrow touring car—nicknamed the “Yellow Devil”—blasted up the gravel road to ascend Pikes Peak in search of the summit and soon became a Hill Climb icon. Many elements have changed since those first motor races to the top of “America’s Mountain,” but the competition is still on the bucket lists of many a car and motorcycle racer, mechanic, and spectator, all hoping to have their own rip-roaring experience more than 14,000 feet above sea level.

This year, when the race runs for the 100th time, more stories will be added to the history of this thrilling, often heart-stopping, event. So we took the opportunity to look back at some moments from its past and present to understand how one person’s savvy marketing idea turned into a sensational international event.

Rugged Beginnings

Beginning as a toll road to offset the cost of construction, the Pikes Peak Highway offered drivers a way to traverse the scenic passage from Cascade to the summit and back for $2.50 per person when it opened on August 1, 1916. Spencer Penrose, the philanthropist and businessman behind many of Colorado Springs’s well-established amenities (including The Broadmoor hotel), dreamt up the car race as a way to advertise his new highway. The first running of the event, soon known as the “Race to the Clouds,” was on August 10–12, 1916, and was covered by more than 650 news outlets nationwide. Driver Lea Rentz won with a run that clocked in just under 21 minutes and sent him back home to Spokane, Washington, with $2,000 in his pocket.

Rea Lentz and his Romano Special in 1916, his one and only—and victorious—attempt at the motor race.

Keen to be a part of the action, Penrose had his personal luxury car modified into a race vehicle and the hand-painted lettering on the side of the car spelled out “The Broadmoor Special.” Easily recognizable in its bold livery, between 1922 and 1932 the Yellow Devil made eight lively attempts to win, but never placed higher than fourth in the Open Class category.

While Penrose was clearly a fan, he never drove the car himself: His chauffeur Harry McMillan, along with Broadmoor master mechanic Angelo Cimino, took turns speeding full-on up the winding curves and switchbacks of the mountain. Although neither racer ever managed to run fastest and thereby earn the coveted King of the Mountain title, the fact that they came in fourth place on two occasions in the heavy, not-designed-to-be-raced vehicle is rather remarkable. And so it has been since the famous race’s inception: Machines, not necessarily designed to be pushed this hard at high altitude and gasping in the thin air, battle to reach the crest, with and against humans who are in an epic endeavor to do the same.

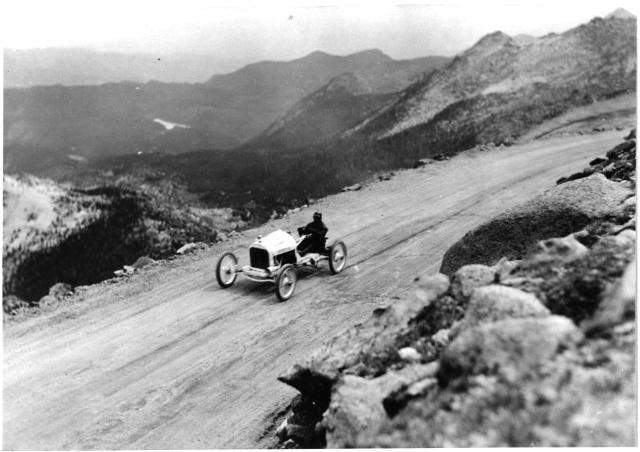

Noel Bullock races his Ford Model T Special up the dirt course in the 1922 Pikes Peak International Hill Climb.

Perilous Climbing

If you have ever driven the road to the summit of Pikes Peak, then you can no doubt imagine how speeding (literally) to the top may not be without significant risks. The highway’s own website offers a guideline for safe driving tips when navigating one of the highest roads in the United States and the maximum speed limit on the road is thirty miles per hour. And as anyone who has spent time in Colorado can attest, the weather can change from pleasant to perilous in a matter of minutes. Now visualize doing all of this above tree line as you try to stick to the road around hairpin turns and blind corners, blazing the straightaways at well over 100 miles per hour—a single vehicle in a race against the clock and the conditions to make it to the top.

While the Hill Climb has always been a hair-raising endeavor, it has actually become more dangerous for drivers in recent years, borne out of the need to better protect the environment. In 1998, the Sierra Club sued the city of Colorado Springs, which was awarded the responsibility of maintaining the Pikes Peak Highway upon Penrose’s passing in 1939. The lawsuit alleged that erosion of the dirt highway was leaving inches of gravel on adjacent forest floors and polluting nearby water sources, which violated the Clean Water Act.

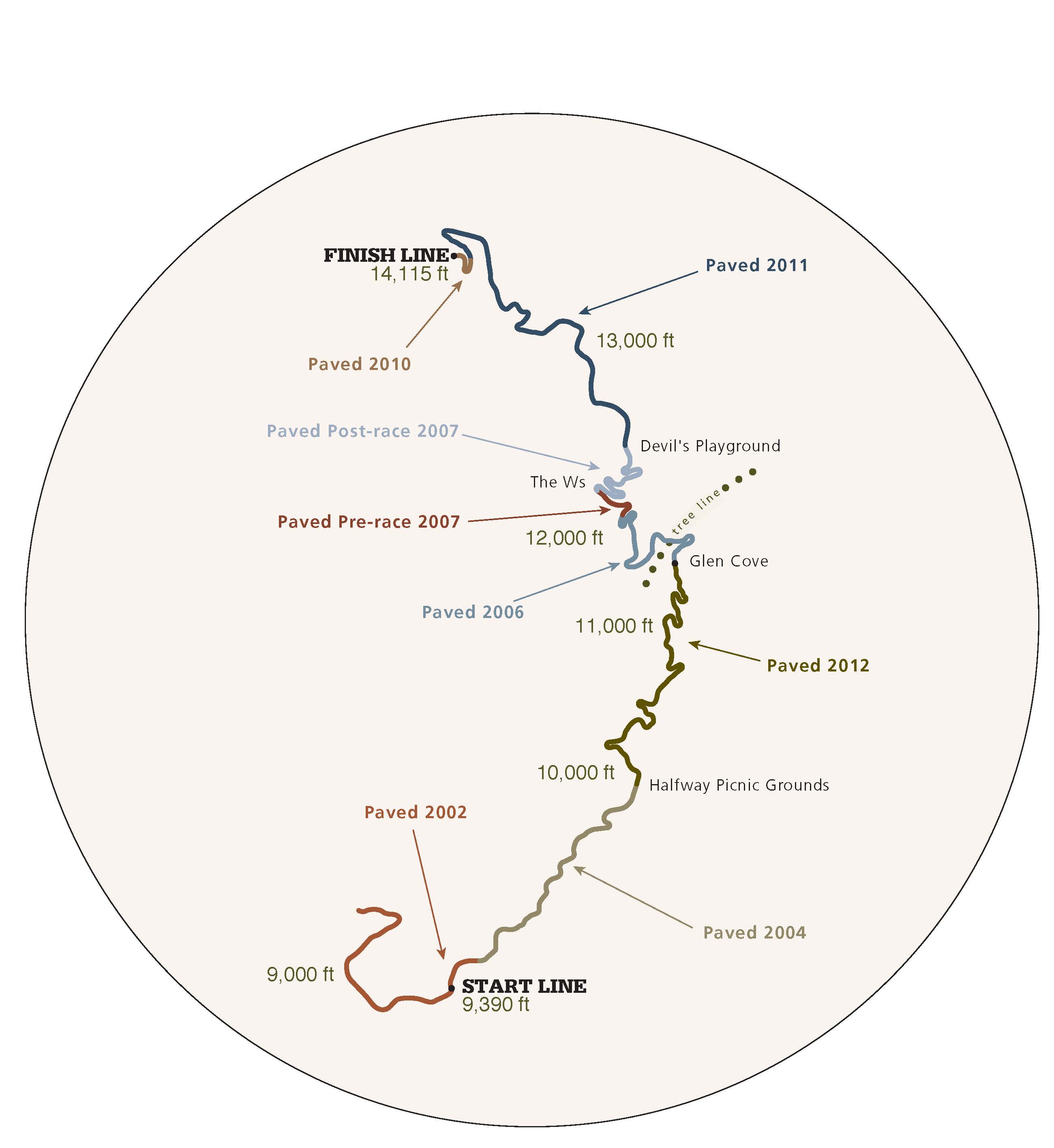

Timeline demonstrating the systematic pavement of the Pikes Peak Highway, starting in 2002.

A settlement was reached between the city of Colorado Springs and the Sierra Club, and the solution was to pave the entirety of the Pikes Peak Highway. The work began in 2002 and, section by section, over the next ten years the dirt was replaced with tarmac in time to make the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb (PPIHC) of 2012 the first to be run on an all-pavement road.

Fortunately, this seems to have improved environmental conditions, but drivers—especially Hill Climb racers—need to be more aware of road conditions than ever before. The tarmac is a faster surface than dirt, which creates obvious challenges on a road with no guard rails. In addition, moisture on the tarmac creates a more slippery surface; the top portion of the track is above tree line and extremely susceptible to adverse weather. These days, race crews at the starting line try to assist in generating as much tire grip as possible by wrapping vehicle tires in warming blankets just before the race, but that cannot account for every condition change a driver will encounter during their twelve-mile quest to reach the top unscathed.

Speed Racer

A sleek red car, emblazoned with the number “62” on its nose, speeds around a corner as a cloud of dust is kicked up behind it. Purple mountain majesties watch from the horizon. The driver sits upright in the open vehicle, laser-focused on the narrow track wrapping around the rocky brown hillside ahead as the road falls away (as in, down) on his right. His gear—white helmet, jacket, face mask, black goggles—are obvious in front of the single roll bar as the camera captures the scene.

This captivating Hill Climb image is one of the first color photos to appear inside an issue of Hot Rod magazine, the oldest magazine about hot rod car culture, first published in January 1948 and still in print today. The image so aptly captures the dirt track, the speed, the colors, and no doubt the imagination of many race admirers. And according to William Taylor, president of the automotive and motor sport library Auto-Archives, the image is a story unto itself. The photo was actually taken the year before it appeared in the September 1962 issue, because at that time, it took too long to process color images for them to be included in a monthly publication. “In those days, they had to do color separations….So they did this real early, and we didn’t know they were even doing it,” chuckles Frank Peterson, who drove that car when the historical photo was captured, and who lives in Lakewood today. Both car and driver did indeed compete again in the race the following year, which coincided with the color photo's debut in the magazine.

Frank Peterson, who oversaw the 2015 restoration of Spencer Penrose's Broadmoor Special, explains how the race car's radiator is comprised of thousands of quarter-inch-diameter copper tubes (5,598, to be exact) separated by 16-gauge wire to facilitate cooling of the vehicle.

Frank Peterson and his wife, Kaye, have become practically synonymous with racing around Colorado. Now in their eighties, the Petersons still work full time at their workshop, Lakewood Manufacturing, near Morrison. I visited the Petersons to learn more about the Hill Climb, cars, and other races, like those at Bandimere Speedway (which they can see—and hear!—from their front door). Frank told me more about that color photo, and the red rocket he was zipping up the track with. It was a Bocar Stiletto, designed by Bob Carnes.

Some twenty-three Bocars are said to have been hand-built by Carnes at his shop that used to be in Lakewood, near Fourteenth Avenue and Harlan Street, until a fire decimated the shop and, not long after, the company. Local lore suggests that at the time of the fire, there were several outstanding orders for the unique fiberglass cars, including from the likes of Augie Pabst, race car driver and member of the Pabst Brewing family, and Lee Iacocca, who became the CEO of the Chrysler Corporation.

Through it all, the Petersons said that the Hill Climb built community. As Frank put it: “Oh, we used to share tools, and parts too. If someone’s car broke, then we would give them a part, or they’d lend one to us.” Kaye added, smiling: “All of the wives used to play together, and the kids too.”

Racing Right Through the Glass Ceiling

The first woman to compete in the PPIHC was Joyce Thompson in her Austin-Healey (Sports Car division) in 1960. While she didn’t win that event, she was the first of numerous women over the years to race, joining a legion of even more female crew members, inspectors, marshalls, and organizers. Kaye Peterson, who operates Lakewood Manufacturing with her husband Frank, has been a mainstay at all of the races her family has participated in, often serving as a welding inspector or some other type of volunteer. She says that although Frank always encouraged her to try her hand at driving, she really enjoys taking part in all of the other aspects of fabrication.

In the century of Hill Climb races, more than fifty women have driven or ridden to the checkered flag. The first female to win her class was French driver Michéle Mouton in her Audi Quattro in 1985 (Rally division), becoming the first woman to be crowned Queen of the Mountain (the winner with the overall quickest time of any class). According to Sarah Woods, Curator of Historic Properties & Archives for the El Pomar Foundation, there will be several women drivers racing for the title again this year, including Loni Unser, the newest—and second female—member of the stellar Unser racing family to vie for the title.

Other past notable women competitors include Katy Endicott, who became the first woman to race an electric car up Pikes Peak in the race’s inaugural Electric Car class, and German motorcycle racer Lucy Glӧckner, who became the first female to finish in under ten minutes, which earned her the title of the fastest woman on Pikes Peak. Yet she was not the first woman to race up the peak on a motorcycle. That honor belongs to Annie Brokar, who did so in 1997 at sixty-one years of age.

Winners in High & Low Tech

Pikes Peak has made a name for itself a proving ground for many new technologies in the transportation industry (including when General Electric conducted testing of airplane engines on the mountain). It is little wonder that, considering the challenging environs on offer at any given moment, “America’s Mountain” provides excellent opportunities to put new ideas to the test—especially when running full-throttle against the elements and the clock.

Motorcycle competitor David Korth races past spectators at the 1976 Pikes Peak International Hill Climb.

Perhaps surprisingly, beyond the rapid-fire thinking and reaction times of the drivers, the race itself also relies on very human-powered technologies. The twelve-mile challenge may be inherently dangerous, but safety is and always has been a crucial consideration. It takes more than 100 volunteer race officials and another 100 volunteers in other positions to run the motor race. And one role is that of a “corner watcher,” which is far more important than it sounds. Although the highway does have cameras lining the road, corner watchers at every one of the 156 corners along the route notify race control immediately of weather changes, stationary vehicles, spectators—or even wildlife—that can pose a danger to race participants.

Another job that makes this gripping race run efficiently? Those who are in charge of timing the race. Sure, the cars have electronic transponders which mark competitors’ times, but there are also hand timers who provide backup in the case of electronic malfunctions, which could mean the difference between winning and losing. The volunteer hand timers at the Hill Climb are incredibly accurate. Alex Feeback, Event Coordinator and Competitor Liaison for the PPIHC, explained that last year they decided to compare the times noted by hand timers with the telemetry data provided by the electronic transponders. As it turns out, the hand timers were an astonishing 99.9% accurate when comparing the data side by side!

Believe and Drive Fast

The tremendous efforts to ensure safety and accuracy for the race mean that its participants can train and come to the mountain prepared to compete to the very best of their abilities, pushing their vehicles, and themselves, to the limit. It is a special breed of racer who receives the coveted invitation to race in the PPIHC, let alone to return to compete year after year, and even generation after generation. Legacy friendships and legacy families are as much a part of racing to the clouds as the cars—perhaps even more so.

King of the Mountain is the title bestowed upon the fastest driver in the Hill Climb each year, and Bobby Unser earned that crown an impressive ten times—more than any competitor in nearly 100 years of racing on Pikes Peak.

The Vahscholtzs, Dallenbachs, and Donners are familiar names to PPIHC fans. And folks will be watching for Rod and Rhys Millen: Father and son will be competing individually in their classes, each of them already holding King of the Mountain titles. The Indianapolis 500 and the PPIHC are the oldest and second-oldest motorsport competitions in the US, respectively, and racing families like the Unsers have been mainstays of both events since practically the beginning. This year, the Unser family will be rallying around PPIHC rookie Loni Unser, the 26-year-old daughter of Johnny Unser who will be climbing the mountain in her 2019 Porsche GT4 Clubsport.

While other drivers may not have famous names in motorsport or hold the crown for the fastest time, being a bucket list event means that there are other drivers out there competing for things besides sponsorship or family titles. I learned from Alex Feeback that invitees from all over the world make up the fifty to sixty competitors (about seventy all together when motorcycles are racing) who come each year and put the “International” in PPIHC—and that over 40 percent of drivers invited to compete in this year’s 100th Running are Colorado residents, maintaining that “local race” feel.

Catch the Race

You can watch, follow on social media, and even listen to this year’s 100th Running of the Broadmoor Pikes Peak International Hill Climb on Sunday, June 26, 2022. Downtown Colorado Springs will also host Fan Fest on Friday, June 24, which draws more than 30,000 visitors and race fans annually.

The rugged terrain surrounding the race course is evident as race driver and vehicle speed past a hairpin turn and continue their ascent.

There are many talented (or, shall we say, driven?) entrants to watch for, including father and son Dan and Trevor Aweida of Boulder, who found enough replacement parts to piece their cars back together after being affected by the Marshall Fire, and Ralph Murdock, who turned eighty-two in May and will be competing for the title in a 1991 Chevrolet IROC Camaro, which was driven in last year’s Hill Climb by his son Kevin.

With so many familiar and local people involved, it is a special thing that this race, which occurs practically in our backyards, has such a broad following. I can only imagine how Spencer Penrose would feel about his racing enterprise now. As Nobihuro “Monster” Tajima, the first racer to break the 10-minute barrier said, “That’s the only secret—believe and drive fast. There is nothing else.”

Which brings us back around full circle to the origins of the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb. While Spencer Penrose’s Yellow Devil was one of the original race vehicles to establish the thrills, spills, and pageantry of this unique event early on, the race itself has continued to inspire participants of all sorts ever since. Racers like the Unsers, who built their cars at home using parts they found in the local junk yard and managed to create a family racing dynasty, to racers like Rea Lentz, who won their first and only race, and never raced again. Then there is the Yellow Devil, whose image helped to catapult the race into the history books, and whose legacy is kept alive by many dedicated custodians including the Penrose Heritage Museum, celebrating its eightieth anniversary this year, and the likes of Frank Peterson, who oversaw the restoration of the Yellow Devil to working order in 2015.

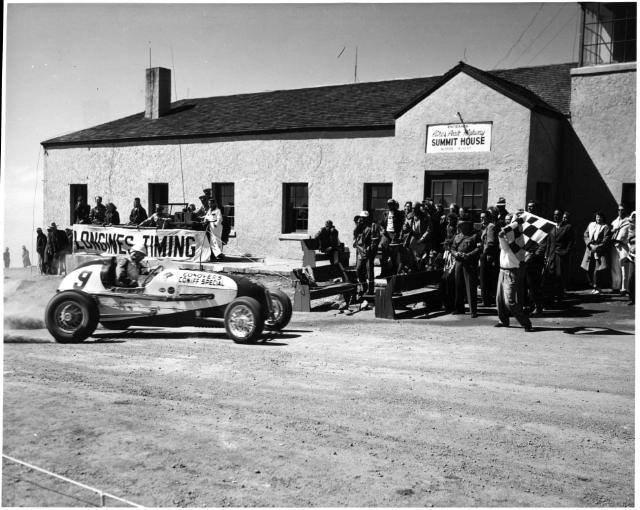

Al Rogers races his Coniff Special toward the checkered flag during the 1949 Pikes Peak International Hill Climb.

One man’s lofty dream, plus the combination of unpredictable weather conditions, fierce acceleration and braking, twists and turns that challenge vehicle handling and tire viability, and the thin air of the peak’s altitude have, over 100 years, created breathtaking practice grounds for car and other manufacturers, as well as the perfect setting for competitors to pit themselves against machine, against nature, and against time—always at the mercy of the mountain. But to me, the enduring charm of the hill climb lives in the stories of the many people who have brought this endeavor to life, and continue to inhale the challenge and exhale the adrenaline that keeps it going.

Correction: The Pikes Peak Highway is one of the highest roads in the United States, not the second highest mountain in Colorado. The article has also been updated to reflect that the city of Colorado Springs and Sierra Club reached a settlement out of court over the pavement issue.