Story

Final Round

A Look Back at How Prohibition Shaped Hop Happy Colorado

John Hanson was greeted with cheers from his fellow detainees when the cops deposited him in the bullpen of the city jail on January 1, 1916. He’d been picked up downtown at Sixteenth and Market Streets for drunkenness. That wasn’t so unusual for a Saturday in a city well-known by then for its raucous saloons. What made Hanson’s arrest newsworthy was that—as of midnight—Coloradans were supposed to be quite sober. He had earned the honor of being the first person picked up in Denver after Prohibition became the law of the land in Colorado. And his hero’s welcome reportedly included a prime spot in the cell where he could sleep it off.

Jailbirds were not the only ones applauding that day. Colorado’s cadre of anti-alcohol reformers were surely celebrating (soberly) as well. Their victory was hard won through force of conviction and grinding effort. Statewide prohibition was on the ballot a number of times prior to 1916, and each time, campaigners failed to expand the ban from dry cities like Fruita, Fort Collins, Greeley, and Boulder to the rest of the state. It was only through on-the-ground political organizing, zealous appeals to religious values, and determined campaigning that the “drys” (as prohibition advocates were known) finally got Colorado voters to ban booze in 1916, doing so four years before the rest of the country followed suit with the Eighteenth Amendment.

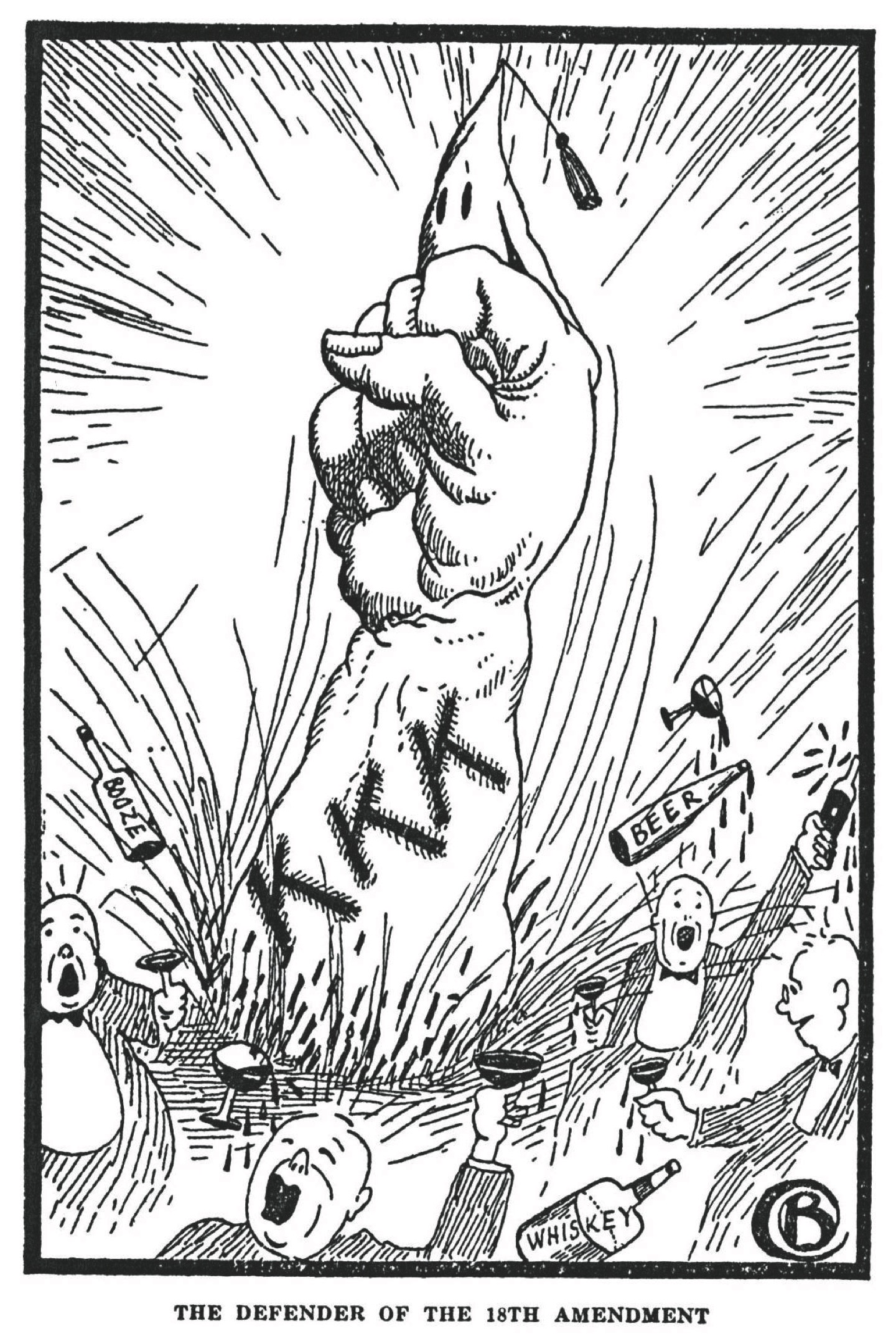

A century later, it seems incredible that a state boasting more than four-hundred breweries (and counting!) helped lead the way towards a booze ban. But looking backward in time through the lens of a pint glass reveals a misunderstood era that’s often obscured by mental images like glitzy jazz-age flappers and speakeasy spirits. In fact, those eighteen dry years were anything but carefree. They saw the rise of organized crime, the resurgence and fall of the Ku Klux Klan, the beginning of the Great Depression, and whiplash-inducing swings in the social role of alcohol. Even the flavor of American lagers today and the current craft beer boom can be explained by looking at the attitudes and habits forged during nearly two decades of Prohibition.

The dry times can seem hazy and distant, and we often overlook the historical forces that made imposing such drastic limits on personal liberty seem like a good idea. Few of us today think about Prohibition when we order our favorite pints at our local brewery or open a cold one at home.

But maybe we should. After all, results of banning alcohol can still be felt in Colorado—from the brewery to the voting booth, and everywhere in between.

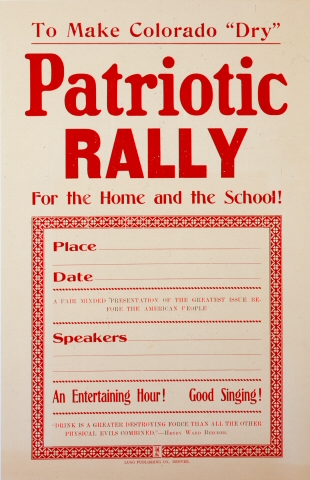

"To Make Colorado 'Dry', Patriotic Rally for the Home and the School! An Entertaining Hour! Good Singing! Drink is a Greater Destructive Force than All the Other Physical Evils Combined."

Demon Saloons

America is beer country. We drink an awful lot of beer here. Our rate of consumption alone proves that we love the stuff. And except for a brief period in the early twentieth century, we’ve always loved it. But never more than in the years leading up to Prohibition.

Industrialization and a massive wave of immigration turbocharged American beer drinking in the late 1800s. Historian and author Daniel Okrent estimated that, as a nation, we were drinking about 36 million gallons of beer a year in 1850. By 1890, he figured that number had increased to 855 million gallons per year. Here’s another way to think about it: in those forty years, America’s population almost tripled while the nation increased its beer consumption rate by twenty four times! By 1914, when beer consumption hit its pre-Prohibition peak, Americans were annually consuming an average of twenty gallons of beer per person. This staggering rise of beer’s popularity in the middle of the nineteenth century wasn’t a simple shift in consumer taste. It reflects the ways immigrants reshaped America.

Millions made their way to the United States around the turn of the century. Racially biased immigration policies meant that most were from European nations where beer culture was deeply ingrained in the fabric of society. The arrival of so many who knew how to make beer—and others for whom beer was an expected part of everyday life—propelled it past cider, whiskey, wine, and rum to become America’s adult beverage of choice. By the twentieth century, the country’s love affair with suds had, in the view of temperance advocates, pushed the nation’s tipplers past a tipping point and painted a target on the saloons where it was consumed.

Beer-pouring saloons were prominent symbols of overdrinking, and so easily became the subjects of political propaganda for pro-dry campaigners. Cities like Denver were nearly covered with saloons. It was almost possible to stumble from one to another clear across downtown in those days. For dry campaigners, their sheer numbers, along with the usual slate of problems associated with overdrinking, made saloons popular symbols of what was wrong with society. And they flogged the issue whenever they got a chance.

One sociologist studying “the liquor problem” in Chicago concisely summarized pro-dry opposition to the saloon in a speech to the city’s ethics committee: “The popular conception of the saloon as a place where men and women revel in drunkenness and shame, or where the sotted beasts gather nightly at the bar, is due to exaggerated pictures, drawn by temperance lecturers and evangelists, intended to excite the imagination with a view to arousing public sentiment.” And arouse public sentiment they did, especially among a new generation of economic and political elites who moved to Colorado in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

When the well-known New York newspaper publisher and utopian idealist Horace Greeley followed his own advice and headed west, he was shocked by what he found. Greeley envisioned the West as a wide-open landscape where Americans would be forged by liberty and opportunity into God-fearing salt-of-the-Earth farmers. They were to be the patriotic and morally-upstanding backbone of America.

But arriving in Denver in 1859, Greeley was sorely disappointed. He found the residents “Prone to deep drinking, soured in temper, always armed, bristling at a word, ready with the rifle, revolver or bowie knife, they give law and set fashions which, in a country where the regular administration of justice is yet a matter of prophecy, it seems difficult to overrule or disregard.”

William Byers, publisher of the The Rocky Mountain News in Denver, agreed with Greeley’s dim view of the city’s early inhabitants. But Byers more directly pinned the source of Colorado’s problems on its listless citizens and its saloon culture: “The throngs of men who line our streets and fill our concert saloons are pursued by infirmity of purpose which drives them from the active ranks of life, and makes barroom fixtures out of them who might adorn society under better circumstances.” Like other journalists and public thinkers in the late nineteenth century, Greeley and Byers equated poverty, unrest, violence, and homelessness with alcohol. The saloon-going man, it was widely understood, was a victim of predatory alcohol peddlers, erosion of social mores, and his own lack of personal fortitude.

By the 1910s, more and more Coloradans were starting to approve of banning saloons and the beers they poured. But growing enthusiasm for Prohibition wasn’t just a result of drunkenness. Saloons were also represented America’s growing ethnic diversity and were becoming flash points in simmering labor disputes.

From their earliest days, Colorado’s labor unions met in saloons. Especially in far-flung coal camps, saloons were often the largest buildings in town, and some of the few locations where laborers could get together away from company men and the job site. Moreover, many were associated with particular ethnic identities or nations of origin. For many folks born elsewhere, saloons and their beers were a little taste of home. In a place like that, laborers could feel free to express their daily frustrations to fellow countrymen in their native language. So when violent labor disputes broke out, saloons (and especially their foreign-born, beer-enjoying patrons) were often cast as the source of the poison in the well.

With saloons representing such a diverse mixture of threats to those controlling Colorado’s levers of political and economic power, they were again obvious targets for divisive political campaigns, this time suggesting that beer causes labor unrest. This impulse to blame beer was callously on display in a 1914 article published across the state describing the context of the Ludlow Massacre. In the article, tellingly entitled “Insurrection in Colorado during the years 1913–1914,” the author and editor of Boulder’s Daily Camera newspaper L.C. Paddock, comes to the defense of the Colorado National Guard who had recently caused the deaths of at least nineteen people. For Paddock, the only “ruthless attack” at Ludlow was the one muckraking journalists made on the brave guardsmen who were simply standing up against anti-capitalist anarchists “declaring loudly against the rights of property.” Paddock’s article emphasized that miners had met in an Italian-American owned saloon adorned with “the red flags of anarchy” to “drink beer and think of blood.”

As the state approached the second decade of the twentieth century, the saloon was being blamed for nearly every social and political problem under the bright Colorado sun. Mistrust of immigrants, labor disputes, perceptions of drinkers’ low moral character, and stark class divisions all manifested in ever-more strident calls to ban beer and the places where it was served. In Colorado, as elsewhere in the country, these sentiments were mostly born out of anxiety over social changes wrought by immigration and the Industrial Revolution. The economic and ethnic divisions between saloon patrons and their critics hardened opinions on both sides of the saloon doors, and discouraged any search for meaningful conversations or compromise.

But just as the miners were not necessarily drinking beer and thinking of blood, temperance reformers were not the anti-worker xenophobic zealots that pro-saloon factions sometimes made them out to be. For lots of temperance advocates, the dry crusade was an urgent response to the very real problem that alcoholism posed in America, as industrialization made beer and other alcoholic beverages cheaper and more widely available than ever before.

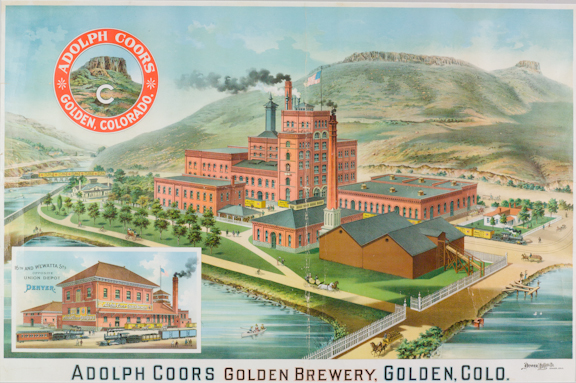

The Coors Brewery in Golden in About 1900. Adolph Coors had become one of the state’s biggest brewers by 1900 when this illustration was made. Steam-powered industrial breweries like his were pumping out thousands of barrels of beer each year.

A Question of Moral and Physical Health

With saloons dotting what may have seemed like every street corner and the nation awash in beer, alcoholism was becoming an increasingly pernicious problem in American society. Beer’s increasing popularity drove a growing sense of alarm. Temperance societies, whose popularity and membership roles had ridden the waves of American religious revivals during the 1800s, found memberships surging across the nation after 1900.

Initially beer was less of a concern. Drys saw it as a compromise— a less-intoxicating alternative to the harder stuff. But as awareness of the very real issues caused by excessive consumption increased, brewers dug in on counter-messaging, insisting that drys were overreacting. The public largely didn’t see it that way, and so brewers found themselves out of step, missing the chance to distance their lower-alcohol products from stronger liquors. As a result, dry campaigners targeted beer along with spirits and wine.

Increasingly strident calls for total prohibition focused on the ways in which substance abuse destroyed individual lives, harmed innocent children and spouses, and frayed the very fabric of society. Seen in these terms, America’s drinking problem was a social crisis that demanded a strong and far-reaching response.

This genuine and urgent sense of alarm spurred some drys to take drastic actions. Carry Nation, Kentucky’s dry campaigner famous nationwide for hacking apart beer kegs and smashing up saloons with a hatchet, did so, in part, because of her first marriage to an alcoholic. Nation, who was arrested for anti-saloon actions in both Trinidad and in Denver in 1906, was not the only woman who felt the ill effects of alcohol on her family. Throughout Colorado, newspaper articles are rife with troubling accounts of alcohol-fueled incidents of domestic violence.

For example, in April 1888, the Fort Collins Courier reported that James Henry Howe, known around town for increasingly abusive behavior, was lynched by an angry mob of vigilantes for murdering his wife while in “a state of beastly intoxication.” Similarly bleak accounts of violence against women perpetrated by drunken men appear in newspapers from across the state. An account from Leadville tells of an immigrant laborer who was arrested in 1914 for threatening his wife and kids with an ax. When questioned by authorities, the local papers quoted the drunk man’s paltry justification for his actions: “My wife, she make me mad. She try to take my hat.”

Stories like these confirmed for many Coloradans the Aspen Daily Chronicle’s conclusion that “overdrinking amongst saloons was a dangerous public nuisance that caused many fatal encounters.” As anti-drinking sentiment grew, newspaper articles increasingly took aim at saloons and beer for being just as detrimental to public health as the viral diseases that made even non-drinkers sick. Asserting a connection between alcohol consumption and pneumonia that reveals an increasing tendency to think about alcoholism as a public health crisis, writers in the Rifle Reveille warned readers in 1913 that, “The United States Health Service brands strong drink as the most efficient ally of pneumonia. It declares that alcohol is the handmaiden of the disease which produces ten percent of the deaths in the United States.”

Likewise, Anti-Saloon League (ASL) and Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) campaigners writing in the Routt County Sentinel in 1913 expressed their frustration that “Boards of health, armed with the police power of the state, eradicate the carriers of typhoid…but alcohol—a thousand times more destructive to public health than typhoid fever—continues to destroy.”

As consumption rates climbed, temperance advocates preached to increasingly receptive audiences across Colorado. The town of Greeley, founded as a utopian agricultural community, was an early Prohibition adopter. So were Fruita and Colorado Springs. Many of Denver’s suburbs, including Highland, Park Hill, and Montclair, were planned as dry communities. Both Fort Collins and Boulder had saloon bans on the books ahead of the 1916 Prohibition vote. Grand Junction voted for Prohibition in 1909 and changed its town charter in order to break the saloon owners’ grip on political power. In each of these places, drys preached about the personal and patriotic virtues of temperance to eager crowds while progressive candidates for political office championed a platform with Prohibition at its heart.

The most strident advocates for reform came from Colorado’s strong Woman’s Christian Temperance Union chapter. Colorado’s WCTU wielded considerable influence, and often flexed political muscle after women won the right to vote in Colorado elections in 1893. Colorado’s WCTU, which was led by organizer and activist Adrianna Hungerford starting in 1904, put its weight behind reform-minded politicians like “Honest” John F. Shafroth and condemned the alcohol-fueled political machine of Denver Mayor Robert Speer. During Shafroth’s tenure as Colorado’s Governor from 1909 to 1913, Hungerford and her fellow reformers at the WCTU continued advocating for total prohibition, and even got a dry referendum on the ballot in 1912.

To help spread the gospel of temperance, the WCTU opened reading rooms where former drinkers could find opportunities for sober self-improvement and a sociable alternative to the saloon. Drys also took to the streets to make known their displeasure with the soggy status quo. One “Patriotic Rally for the Home and the School” promised attendees an “Entertaining Hour” with “Good Singing!” to demonstrate against alcohol and show that drinking was not the only way to pass the time.

Colorado’s movement to ban beer picked up considerable momentum in 1914 with the outbreak of World War I. The US was at war with Germany, and even the saloon-going residents of suds-loving Denver began to look upon beer—and the predominantly German men who made it—with deep suspicion. Anti-German sentiment was on the rise, and brewers’ belated efforts to market beer as a safer and more wholesome alternative to hard liquor fell on increasingly deaf ears. From immigration and labor disputes to domestic violence and the disease of alcoholism, Prohibition, it seemed, could be a panacea for the problems confronting Coloradans. Far from curing Colorado of its ills, however, banning beer created many more problems than it solved.

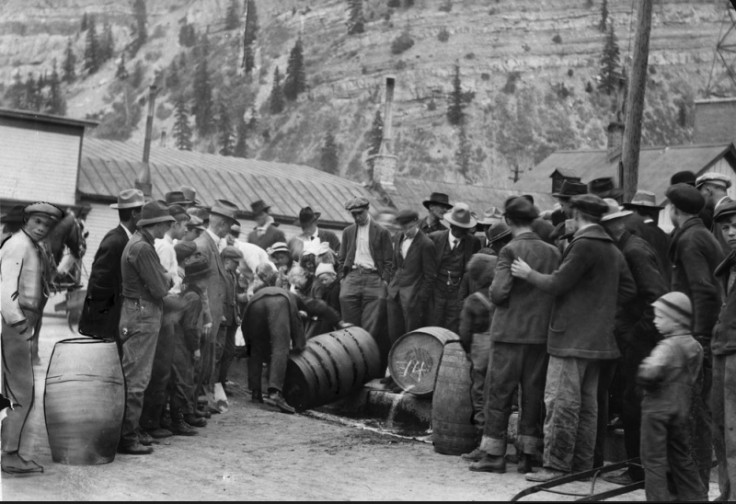

"First Prohibition Bust in Ouray." Commercial alcohol had been illegal for a little over four months on May 7, 1916 when this barrel was seized and poured into the gutter in Ouray.

“Who Cares If We Make a Little Beer?”

Most of Colorado’s breweries were as dry as its Rocky Mountain air on the first day of 1916, and generally speaking, folks filed out of saloons and stopped imbibing. Law abiding citizens who had been accustomed to incorporating drinking into their regular routines reorganized their activities around new social outings, including trips to the movies.

Temperance reformers were initially buoyed as local churches and voluntary associations like the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks replaced saloons as the most important sites of social organization. For Adrianna Hungerford and her fellow drys at the WCTU, the statewide liquor ban was the ultimate victory. The state, now clean and sober, could face the world with optimism for its citizens’ moral and physical health.

But what about the large minority of citizens who voted against Prohibition? After all, Colorado’s vote on Prohibition was extremely close. Drys barely carried the day with their 129,589 votes (52 percent of the total) against the 118,017 votes (nearly 48 percent) from wets—a narrow victory of only about 11,500 votes. With all of Colorado’s breweries prohibited from selling their product, thirsty beer fans had a choice: turn to non-alcoholic malt tonics and “near beer,” or start making their own.

Before Prohibition, alcohol-free malt tonics colloquially called near beer were marketed and sold as a health drink by druggists in pharmacies. When full-strength beer was outlawed, several Colorado breweries ramped up their production of malt tonic due to initial demand and profitability. But beer’s buzz is an integral part of the experience, and brewers quickly found out that their non-alcoholic product was as disappointing to drink as it was to make. Drinkers and brewers quickly decided that there was no substitute for the real deal.

The biggest Colorado breweries—Coors, Tivoli, and Ph. Zang among them—rode out the first few years of Prohibition making near beer, but it wasn’t enough. Coors started making malted milk and high-quality porcelain to keep its workers employed. But despite brewers’ best efforts to offer enticing legal alternatives, Coloradans who wanted a real beer increasingly turned to making it at home.

Homebrewing was a viable option for thirsty and industrious Coloradans during Prohibition since, in perhaps the most effective encouragement of homebrewing ever codified, the legislators who wrote Colorado’s Prohibition amendment initially declined to outlaw alcohol possession in private residences. Wealthy Coloradans such as Spencer Penrose—founder of the extravagant Broadmoor hotel in Colorado Springs—took advantage of this loophole by stockpiling cellars of booze that they hoped would carry them through Prohibition. But those with lesser means had to brew their own Prohibition potions.

Notable among them was a man named J. L. Williams of the Mt. Harris coal camp west of Steamboat Springs who began homebrewing in 1917. When state enforcement officers came around to check out his operation, they did not dispute his right to brew, but Williams’s production of a barrel a day struck them as suspicious. The agents arrested Williams on charges that, according to the Steamboat Pilot, he “was making more beer than he could possibly drink himself, even with his acknowledged abnormal capacity, and he had been selling to others of the coal camp.” Williams protested his innocence and claimed that he drank all he brewed, but his case illustrates the brazenness with which Coloradans flouted the new laws when beer was on the line.

Speakeasies, the underground saloons that loom so large in our imaginations as glitzy secretive night clubs, popped up in nearly every town almost immediately following Prohibition. But few served beer in the same way as saloons of old since distilled liquor was more profitable per bottle and easier to transport—not to mention simpler to hide from the cops. In contrast to the way beer was consumed in saloons, Prohibition-era beer became a beverage that people mostly made and drank at home.

Denver held its fair share of homebrewers, and stories suggest that homebrewing was a widespread hobby around the state. Even Denver’s famed composer and jazz musician George Morrison Sr. got in on the action. The Denver Public Library provides an account of the family’s activities from his son. Recalling growing up during prohibition in Denver’s Five Points neighborhood, George Morrison, Jr. tells us “Dad made home brew. Once during the night when Bill “Bojangles” Robinson was visiting us, beer started exploding in the cellar. It was a common occurrence, so it amused the family when Bojangles woke everyone up yelling, ‘What’s that, what’s that!?!”

Aspiring homebrewers didn’t need to be sophisticated in the brewer’s arts to create drinkable beer. National beer retailers like Blatz, Schlitz, Budweiser, Miller, and Pabst all lent homebrewers a helping hand by selling some version of malt syrup —the glutenous product that contains all of the sugars needed for fermentation—in drug stores throughout the nation.

Marketed as a sweetener for baked goods, much of the malt syrup sold during Prohibition was hop-flavored, surely leading some honest-minded shoppers and government officials to wonder who exactly was consuming all of this bittersweet bread. By 1926, Anheuser-Busch was doing a bang-up business selling more than six million pounds of malt extract every year, prompting brewery chairman August Busch Jr. to tell an interviewer that his company “ended up as the biggest bootlegging supply house in the United States.”

As any modern homebrewer will tell you, making beer with malt syrup or malt extract is a pretty simple process. Stirring the sticky sweet syrup into a pot of boiling water and adding some bittering agent like hops and some yeast is about all you need to do to create a brew that is reasonably close to what the professionals make. And if the professionals aren’t making anything, then homebrew made from malt extract tastes all that much better. During Prohibition, police tended to overlook small homebrewing operations, and courts were hesitant to penalize those who used malt syrup for something other than its supposedly intended purpose. A Chicago man voiced the operating premise of many of his fellow scofflaw homebrewers when he explained that “Maybe the police wouldn’t like it so much if we had a still, but who cares if we make a little beer for our own use?”

For Denverites, that analysis proved sound even after homebrewing became illegal when the rest of the nation passed Prohibition in 1920. Denver’s District Attorney John Rush indicated at the outset of national prohibition that he was uninterested in prosecuting thousands of homebrewers. In Ambitious Brew, Maureen Ogle found that so much homebrew flowed beyond the capacity of law enforcement to do anything about it that in 1933 August Busch Jr. declared, with a tinge of jealousy, “Home-brewing has been the great indoor sport in millions of American homes since 1920.” Coming from the head of arguably America’s most successful brewing family, his sentiment affirmed the age-old truism that when Americans can’t buy professionally made beer, they tend to figure out how to brew it on their own.

Moonshine and Mobsters

Despite the ease and popularity of making beer at home, the fact remains that most of the alcohol consumed during Prohibition was harder stuff: wine and liquor. Americans who could afford to pay bootleggers’ prices looked to illegally imported bottles from Canada or Mexico and supported a clandestine web of moonshiners throughout the dry years. For those with more modest budgets but lacking the inclination to homebrew, spirits were the best choice as they were more widely available and much cheaper to obtain than illegally imported beer. Spirits were on hand in Colorado throughout the dry years, thanks in part to organized criminal outfits for whom Prohibition provided a lucrative source of revenue.

Italian-American immigrants were some of the first to coordinate large-scale, organized moonshining and bootlegging in Colorado. Up until 1916, the shadowy criminal organization known as the Mano Nera or Black Hand had a small presence here. Criminals acting on their own or Italian immigrants familiar with the very real threat of organized crime in the old country would use drawings of black hands as scary graffiti or as a sort of bogeyman to back up threats.

Within Italian-American immigrant communities, some who had endured personal slights invoked the mystique and fear-inspiring reputation of the Black Hand to underscore the seriousness of retaliatory threats (whether bogus or real). But organized crime was still rare in Colorado before Prohibition, and those few real mobsters who operated here mostly concentrated their efforts on small-time gambling and extortion rackets.

As the state went dry, however, those would-be gangsters recognized that the public’s desire for alcohol hadn’t subsided. They also recognized that, because booze was illegal, thirsty people would be willing to pay more to get it. At first, most of the alcohol trafficked in Colorado was wine—a vital part of many cultural and religious lives, and not something that everyone wanted to give up in spite of the ban. But moonshine and illegally imported liquor quickly became the most popular of illegal spirits.

Enterprising bootleggers in Pueblo and Trinidad started making and secreting away their supplies, and tunnels dug underneath Smelter Hill in Pueblo were a particularly popular hiding spot. As Prohibition expanded to the rest of the nation, illegal distilling operations exploded throughout the state. Not all of these operations were run by the nascent mob, and Coloradans of all backgrounds eagerly engaged in the liquor trade. But Prohibition turbocharged the rise of mafia organizations across the country. And in Colorado, two families in particular—the Dannas and the Carlinos—vied to dominate the state’s bootlegging operations from their home-bases in Pueblo.

With many thousands of dollars in ill-gotten revenue on the line, the fight over the southern Colorado liquor trade quickly turned violent. Deadly shootouts in the streets of Pueblo happened with frightening regularity and came with grotesque results. Several members of each family met grisly fates at the business ends of sawed-off shotguns. The bloodshed finally subsided after the Carlinos succeeded in wiping out the competition, driving the Dannas out of the liquor business. After establishing control over southern Colorado’s bootlegging trade, Pete Carlino turned his attention north towards the Denver area where Giuseppe “Joseph” P. Roma was building a bootlegging empire.

Roma thrived even amid the violence of Prohibition and built a large operation bringing illegal booze into Denver. But even the end of Prohibition couldn’t save him from the violence that accompanied the illegal liquor trade: Roma himself was murdered in his North Denver home in 1933, making way for Clyde and Checkers Smaldone—two of Roma’s associates—to become Denver’s most infamous mobsters. The Smaldones’ influence endured through Prohibition and well into the post-war era, though today many Denverites know the family for Gaetano’s—their Italian restaurant in the city’s Highland neighborhood.

Running battles between bootleggers persisted throughout Prohibition, leading some to wonder whether the purported goals of banning alcohol—to cut down on the lawlessness and violence of the saloon days—were attainable at all. Clever criminals seemed to always be one step ahead of the law, and especially in the early days of Prohibition, took advantage of a woefully underprepared law enforcement system.

In the early twentieth century, Colorado didn’t have a state-wide law enforcement agency. Though Colorado’s 1916 Prohibition law provided for the commission of special officers known as Prohibition Executive Agents, they were too underfunded and too understaffed to cover Colorado’s 104,185 square miles. Thus, responsibility for pursuing and apprehending offenders often fell to municipal officers or county sheriffs whose authority to enforce the law ended at the town or county line. Colorado bootleggers took advantage of the jurisdictional boundaries and, if pursued by the local cops, would scoot across county lines, wait for the heat to die down, and then proceed with their deliveries.

Though many law enforcement officers did their best to stem the flow of illegal booze around the state, there was too much demand and too much money to be made from bootlegging and moonshining to stop the scofflaws. Bribes greased many palms, and cops often looked the other way. Despite the high demand for booze, many Coloradans quickly became fed-up with the effects of going dry on crime and the economy. The Denver Post voiced the frustration many Denverites felt with their police by remarking that it would be great if Denver’s Chief of Police Robert F. “Diamond Dick” Reed and his officers could “catch something besides a cold.” Desperately seeking safety and security in their communities, many people were willing to support anyone who promised a solution to rising crime. In the first half of the 1920s, that solution for an alarming number of Coloradans came from the Ku Klux Klan.

Colorado’s Klansmen positioned themselves as a vigilante Prohibition enforcement gang to help legitimize their discriminatory and xenophobic agenda. Under the guise of aiding the police to bust bootleggers and fight crime, the Ku Klux Klan sent the message that anyone who wasn’t white and Protestant was not welcome in Colorado.

Prohibition Fuels the Rise of the Ku Klux Klan

By the time the rest of the nation followed Colorado’s lead by going dry in 1920, the Ku Klux Klan had already targeted Denver for expansion. The KKK found eager recruits, especially in communities still struggling to integrate immigrants and control the flow of illegal alcohol. In these places, respect for law and order became the Klan’s rallying cry. Much of the virulent nativism and racism Colorado’s Klan espoused in the early 1920s, writes Robert Allen Goldberg in Hooded Empire, was tied to the new immigrants one Las Animas County Judge called “foreigners, who by education and training believe in the use of intoxicating liquors.”

This anti-immigrant and anti-alcohol message found receptive audiences throughout the state. After enduring shocking violence over control of the liquor trade, many of Pueblo’s Anglo-Protestant residents welcomed the Klan and its promise to clean up the city. The KKK’s public debut in Pueblo came in 1923 with a series of induction rallies. In June of that year, an estimated 3,200 Klan members from across Southern Colorado gathered in a field north of town to induct 200 new members into the Pueblo Klavern (the KKK’s term for local Klan cells). The scene repeated itself again in September with several hundred more members swearing fealty to the KKK and joining together to burn crosses, eat barbeque, and sing hymns.

One of the Pueblo Klavern’s first major actions was undertaken in February 1924 in response to a grand jury’s finding that the police department was either inept or corrupt, and hadn’t done enough to enforce prohibition in Pueblo. With about fifty Klan members backing him up, Klansman and county Sheriff Samuel Thomas took the law into his own hands, leading a series of liquor raids in South Pueblo. Going from house to house, Klansmen searched the homes of Hispano residents and Italian immigrants for illicit booze or the means to make it. Thomas only made seven arrests, and almost all of those searched and arrested were Catholic. The message the Klan sent was clear: white Anglo-Protestants blamed the community’s Hispano and Italian-American residents for flouting prohibition, and they were willing to take enforcement into their own hands if the police couldn’t handle the job in the way these vigilantes preferred.

White supremacy, religious discrimination, and anti-immigrant xenophobia remained major platform planks for the Klan in Colorado as Klaverns solidified their footholds in Southern Colorado throughout 1924. By continually reminding residents of the link between bootleggers and immigrants, the Klan veiled their racist intentions behind a veneer of patriotic vigilantism.

In Walsenburg, south of Pueblo, 350 Klansmen paraded silently through the streets on a chilly January morning bearing American flags and banners with slogans like “The Bootlegger Must Go” and “America for Americans.” Cheers and enthusiastic applause met the Klansmen all along their parade route, which underscored just how influential the KKK had become in Colorado. Klaverns appeared in Trinidad and other Southern Colorado towns, and held similar rallies and to prey on fear of immigrants and pent up frustration with the local police department’s feckless response to bootlegging.

This exasperation was particularly acute in Denver. As the biggest city as well as the state’s financial and political center, Denver eclipsed even Pueblo as a regional hub for the liquor trade, making it a ripe target for Klan organizing. Speakeasies dotted the city, and bottles of booze were easy to find if you had the cash to pay black market prices. Despite help from a dedicated but undermanned corps of Prohibition police, Denver cops were just as helpless as those in Pueblo at stamping out bootlegging and violence that went along with the sale of illegal booze. The Denver Express reported on the unprecedented “wave of lawlessness sweeping Denver” in 1921.

Just like in the rest of the nation, Denver police were generally ineffective at apprehending bootleggers, and residents were frustrated that the police were unable to bring about the promised social benefits that were supposed to come with the dry laws. Homebrewers went almost completely unpunished, and individual drinkers usually slid under the radar. Even when the cops did catch the odd tippler or homebrewer in their dragnet-style Prohibition sweeps, prosecutors were hesitant to bring charges against individual drinkers or brewers, and juries were equally hesitant to convict.

So, much to the annoyance of many local residents, Prohibition scofflaws—a term that was coined during Prohibition specifically for them— walked free more often than not. Making matters worse was a pervasive knowledge that the Denver police department was rife with corruption. Some of the police force was indeed on the take, as mobsters with rolls of cash found cops willing to look the other way. Corruption was so extensive that in 1923 Denver’s district attorney was quoted in The Denver Post as saying “The present city administration is a disgrace to American government.” Just like elsewhere in Colorado, the situation proved ripe for exploitation by the KKK.

Arriving in Denver in the spring of 1921, organizers for the Atlanta-based Klan found fertile ground among men of the city’s white and Protestant population who were fed up with rising crime. Organizing these men on the ground and protecting the Denver Klavern from the city’s anti-Klan reaction was a job eagerly filled by a local physician named John Galen Locke. Born in New York in 1873, Locke moved to Colorado in the early twentieth century. He was a charismatic leader with a genius for effective organization and theatrics—traits he would employ to extend the Denver Klavern’s control over state and local government.

The Denver Klan’s first opportunity to grab the levers of political control came during the mayoral election of 1923. Running as a Democrat and promising to address bootlegging and corruption, Benjamin F. Stapleton beat incumbent Dewey Bailey with broad support from important institutions like The Denver Post as well as powerful individuals including his personal friend John Galen Locke. Despite his well-known affiliation with the KKK, Stapleton won and appointed Klan members to fill positions at all levels. Notably, however, Stapleton initially refused to appoint a Klan member to lead his police department, fearing (correctly, as it would turn out) that mixing the Klan and the leadership of the police would bring about disastrous results for Denver’s residents as well as his political image.

By 1924, just months after he took office, the chorus of Denverites questioning Stapleton’s integrity was growing, and citizens of the metropolis initiated a recall campaign explicitly motivated by their mayor’s obvious entanglement with the Klan. In order to defeat the recall, Stapleton was forced to whole-heartedly embrace the KKK and its aims. To appease Locke and show his gratitude for their staunch support (and their $15,000 campaign donation), Stapleton appointed William Candlish to be the new Chief of Police. Candlish had no police experience and no qualifications other than his Klan connections. His appointment was certainly connected to Stapleton’s campaign pledge to “work with the Klan and for the Klan in the coming election” and to “… give the Klan the kind of administration it wants.”

Stapleton won his recall election thanks to Locke’s political organizing. After celebrating their victory by burning a cross atop South Table Mountain in Golden that was so large the fire was visible in Denver, the Denver Klavern acted with even more impunity. With William Candlish (who gained the nickname Koka-Kola-Kandlish for his overt displays of his Klan connections) at its head, the Denver police department turned into one of the primary vehicles by which the Klan executed its agenda of intimidation. White Protestant officers were asked to become Klan members, and those who did were, in the words of historian Robert Alan Goldberg, “rewarded with choice assignments, shorter hours, and promotions. The rest joined Jewish and Catholic police officers working night shifts on undesirable beats.”

At Candlish’s direction, these new Klan members within the police department concentrated on Prohibition enforcement efforts in Denver’s Black, Jewish, and Italian neighborhoods. The Denver police initiated a widespread campaign of terror and repression in the guise of enforcing Prohibition. Officers cited obscure and semi-forgotten laws as they terrorized and intimidated non-white, Jewish, and Catholic shop owners who carried government-permitted sacramental wines. In Five Points, Denver’s historically Black community, Klan-affiliated police used speakeasy raids as their preferred tool of intimidation, and went house-to-house searching for illegal beer and spirits. Despite lingering anti-German sentiment following World War I, the Klan did not target German-Americans or even former brewers in any meaningful way. All across the city and the state, Prohibition enforcement became an excuse for sending an unmistakable message: unless you are white and Protestant, you are not welcome here.

The Klan reached the height of its influence in Colorado after winning several statewide offices including the governorship in 1924, and the organization’s white supremicist agenda appeared poised to dominate Colorado politics for some time. But mastering the means of obtaining power was a different thing than exercising it. As the decade wore on, Klan-backed politicians found that Prohibition enforcement was a less appealing message when it was coming from a group with such obviously anti-democratic and discriminatory aims.

As a result, Klan support ebbed in the latter half of the 1920s, and by the time Prohibition was repealed in 1933, Colorado’s Klan had all but dissolved. Stapleton distanced himself from his hooded patrons, and Locke was forced out of the Klan after a well-publicized arrest for tax evasion. Though KKK political dominance ultimately proved to be a flash in the pan, its use of Prohibition enforcement as a guise for more sinister discriminatory action was an effective political move that helped legitimize the more odious planks of its hateful platform.

Repeal: Beer Leads the Way Back

By the 1930s, the nation that clamored for Repeal was not the same one that lobbied for Prohibition. Much of the change in sentiment was a result of the Great Depression. Beginning with the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and lasting throughout the 1930s, the Depression fundamentally re-ordered social and financial priorities in American homes and in the halls of Congress. Throughout Prohibition, badly needed tax revenues from liquor sales were not collected. Instead, those dollars were shunted into bootleggers’ pockets.

The cost of enforcing Prohibition compounded the revenue problem for Depression-era governments at all levels. As the crisis wore on, the hypocrisy of Prohibition was laid bare as voters saw enforcement efforts focused on poorer communities, while the rich were largely allowed to consume without consequence. So by 1933, with the Great Depression sowing despair and Prohibition’s failure to deliver on its promises in full view, many more Americans were thinking that they could really use a (legal) drink.

As Repeal dawned across the nation, beer led the way back. Brewers and pro-Repeal groups argued that beer was not as intoxicating or dangerous as liquor or wine, and successfully lobbied the government to classify low-alcohol beer as “non-intoxicating.” This expedient got beer flowing and people back to work as quickly as possible because it exempted weak beer from federal Prohibition laws. Brewers were therefore able to deliver beer that was 3.2 percent alcohol without waiting for full repeal, and so by April 7, 1933, legal beer was again for sale in the state.

The Cullen-Harrison Act (which brought low-alcohol beer back) filled in the gap until the Twenty-First Amendment could be ratified by the states. Weak beer was on sale throughout the summer and fall of 1933, but liquor and stronger beer sales waited for Utah to provide the deciding vote ratifying the amendment on December 5 (Colorado had voiced its approval in September.) Even with the full return to legality on the federal level, the states would need to re-write their own alcohol laws—all of which had been nullified by the Eighteenth Amendment in 1920. In Colorado, legislators argued with each other through that first week of April 1933 about whether to allow municipalities a “local option”—laws that would allow specific towns to stay dry and enforce a ban on even low-alcohol beer. Lawmakers in support of self-determination at the community level prevailed, leaving cities across Colorado—including Ft. Collins, Greeley, and Boulder—to continue enforcing Prohibition within their limits as the rest of the state embraced Repeal.

But those across Colorado hoping to welcome beer back with a late-night cold one were disappointed. Most who said farewell to legal beer at the outset of Prohibition with lemonade toasts may have found themselves welcoming Repeal in the same manner. The Rocky Mountain News reported that “Hotels are planning no beer party celebrations for tonight. Whatever celebrating is done, has been left entirely to individuals in Denver—and there is little likelihood many of them can obtain the beer for such a celebration before tomorrow night at the earliest.” One reporter covering the non-event in an article headlined “Beer Becomes Legal Here but City Sleeps Thru It” noted that “You couldn’t hear a quaffing sound any place.”

Coors and Tivoli-Union—the only two breweries in Colorado ready to ship their product on April 7—discouraged a boisterous welcome back. They feared raucous parties would give voters second thoughts about Repeal. And they had good reason to be worried: committed Prohibitionists clung to hopes that legal beer would either slake the nation’s thirst or prompt enough bad behavior that it would horrify lawmakers into realizing their mistake and put a halt to the full Repeal campaign. But the brewers refused to play into their hands. ‘We’re not in favor of any national holidays,’ said one brewer [to a reporter from Denver’s Rocky Mountain News]. ‘We plan to conduct a decent, respectable merchandising business and we will start the sale of our product on that basis.”

When the taps finally started flowing the next day, “the rush to sample the beer exceeded the expectations of the most enthusiastic sponsors of the beverage.” Supplies quickly ran low in the face of overwhelming demand, but revelers remained on their best behavior. The Rocky Mountain News reported that, whereas Denver had been averaging three to ten arrests per night for drinking during the waning days of Prohibition, there were “no arrests, auto accidents, or disturbances of any kind” as Denverites welcomed legal beer back. The open presence of women at the celebrations added to the strangeness of that day for some, since co-mingled public drinking would have been uncommon before Prohibition. In a dramatic demonstration of just how many changes Prohibition had wrought, Denver’s servers reported that “women were among the enthusiastic samplers of the beverage in its initial day.” The paper even ran a photo of smiling, well-dressed women raising a stein with the men to prove it.

After Repeal, the most visible change in Colorado’s beer landscape was the absence of saloons, which never regained their central role. Even those who had worked hardest to defeat Prohibition did not intend to welcome the saloon back to its former place in American life. Pauline Sabin, enemy of Prohibition and leader of the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform, made it clear to reporters in 1933 that she was in no way advocating for a return to pre-Prohibition ways: “I can’t conceive of the old saloon being allowed to come back,’ she said. ‘Of course, if you mean by a saloon a place where liquor is bought and consumed, it will come back, but there will be improved conditions.”

Brewers took her point (or perhaps her warning) and, in place of the saloon, began promoting the home as the proper setting for enjoying a cold one. Once again using a suite of technological advances to transform the industry, brewers took advantage of the widespread adoption of refrigerators and radios in American homes during the 1920s and 1930s to move beer out of the saloon and into the home. The vinyl-coated or “keg-lined” steel beer can, introduced in 1935, was a major catalyst for the shift. Cans were less expensive for brewers to produce, and they were easier for consumers to store in the refrigerator. In-home mechanical refrigerators had been a rare luxury at the beginning of Prohibition, but by 1933, they were in a quarter of American households, allowing Americans to grab a cold one with unprecedented ease.

The trick for brewers was actually getting consumers to buy their beer at the grocery or liquor store. To do so, marketers focused on convincing middle-class women (who they assumed did the shopping for their household and who had been the moral force of the temperance movement) to view beer as a household staple and an important component of the American Dream, rather than a threat to their family. Keeping the fridge stocked for the men in their lives would, advertisers suggested, keep those men from heading out to drink in bars and would promote domestic happiness. As radios became common household appliances through the 1920s and 1930s, marketers found that sponsoring programs intended for housewives was an effective way to convince women to buy their products.

The brewers’ message quickly took hold: whereas 90 percent of beer before Prohibition had been packaged in kegs destined for saloon taps, by 1935, about a third of all beer was shipping in cans and bottles. By 1940, nearly half of all beer came in packaging meant to be consumed at home. In order to appeal to a wider range of palates, some brewers lightened their lagers, tamping down the “beer flavor” and lowering the alcohol content. Brewers reduced the amount of malt in their recipes and mixed in more additives with milder flavors. Hops were cut back to a minimum. The result was a style of American lager that was (and is) easy to drink.

Changes in the way it was made and marketed reflected a brand-new understanding of beer’s place in society. Co-ed drinking was a rarity in Colorado before 1916, but the necessarily underground nature of alcohol consumption during Prohibition, when mixed with the shifting social norms of the Roaring ’20s, enabled men and women to drink together in public establishments. With Repeal came a more relaxed attitude toward beer consumption, and advertisers across the nation encouraged this change by positioning beer as the perfect accompaniment to every household event. By the 1950s, industry advertising pushed beer into a new role. Not only had beer become a backyard beverage, it had morphed into a basic element of home life in post-war America.

Today, of course, Colorado is known for beer. Until recently, it was the headquarters of Coors, and our brewing industry currently leads the nation in terms of per-capita economic impact. We have more breweries than all but four other states, and still host the nation’s largest craft beer and home brewing competition: the Great American Beer Festival. It is quite the turnaround given our position in the vanguard of states banning brews just over one hundred years ago.

Those tumultuous eighteen years of Prohibition left a lasting mark on our attitudes towards alcohol, and utterly reconfigured the legal, economic, and social landscape of Colorado. We often think of Prohibition in terms of exciting speakeasies and glamorous flappers. But in Colorado, homebrewers, sawed-off shotguns, and Klansmen’s hoods are perhaps equally fitting symbols of the times.

For Further Reading:

Anyone interested in learning more about Prohibition owes a deep debt of gratitude to Daniel Okrent for his book Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. It really is the definitive book on the subject, plus it’s a great read. Lisa McGirr’s Prohibition and the Rise of the American State is a perhaps more focused account connecting the dots between Prohibition, the expansion of police power, and the government’s involvement in Americans’ daily lives.

Closer to home, historians Elliott West and Tom Noel have both written excellent books examining the role of beer and saloons in Colorado history. West’s The Saloon on the Rocky Mountain Mining Frontier and Noel’s The City and the Saloon: Denver, 1858-1916 provide eye-opening glimpses into the social roles of saloons in Colorado and beyond. They also contain tragic, funny, and shocking true tales—that wonderful combination which makes for great books to talk about over a pint. Likewise, Maureen Ogle’s book Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer would be a fantastic read with a brew in hand. We also owe a debt of gratitude to Nathan Michael Conzine, whose 2010 article “Right at Home: Freedom and Domesticity in the Language and Imagery of Beer Advertising, 1933-1960” in the Journal of Social History helped show us how effective beer can be at tracking change in American history.

Much has been written on the rise and fall of Colorado’s mafia. Dick Krek’s Smaldone: The Untold Story of an American Crime Family is perhaps the most famous resource about organized crime in Denver. But Betty L. Alt and Sandra K. Wells’ Mountain Mafia: Organized Crime in the Rockies is another great resource for those curious about the Southern Colorado mafia. Much less has been written about Colorado’s KKK. Robert Alan Goldberg’s forty-year-old Hooded Empire: The Ku Klux Klan in Colorado remains the definitive history of their dramatic rise and fall. For a more national perspective on how the KKK rose to such prominence in the 1920s, Linda Gordon’s The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition would be an excellent choice.

Source material for many of the stories in this essay came from the Colorado Historic Newspaper Collection. Their repository of many Colorado newspapers contains some of the earliest published in Colorado, and makes a historian’s job easy. Articles from the Rocky Mountain News and the Denver Post aren’t accessible there, but the crack team of researchers at History Colorado’s Hart Research Center can help anyone interested in searching those publications.