Story

An Almost-Forgotten Fight for School Desegregation

The 1914 Maestas suit was one of the country’s first successful legal fights against discrimination in schools. And it may have been the earliest involving Mexican Americans.

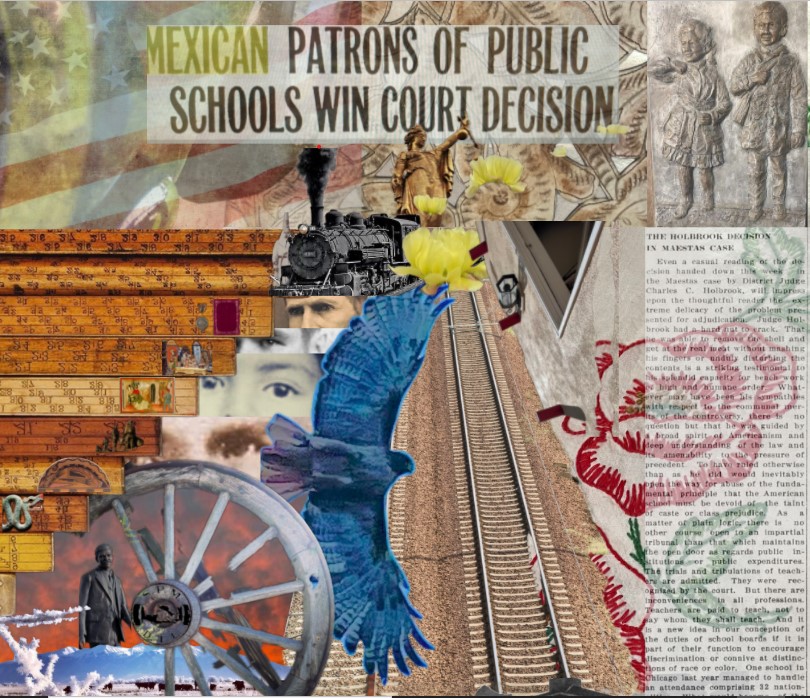

Four decades before the landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision made integrated schools the law of the land, a little-known lawsuit successfully challenged school segregation in Alamosa, Colorado. Maestas vs. Shone was part of a fight against discrimination that set the stage for modern-day civil rights campaigns in Colorado. And, until recently, it was largely unknown.

Alamosa is the biggest town in the biggest alpine valley in the world. The San Luis Valley, straddling southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, boasts eleven mountain peaks exceeding fourteen thousand feet. It is sixty-five miles east to west, and stretches 125 miles north to south, making it larger than the state of Connecticut. The Valley, as it is commonly called, is home to Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve and serves as the headwaters of the Rio Grande.

The Valley was home to Puebloan cultures as well as the Ute, Diné, Apache, and other Indigenous peoples before it became a part of Spain’s colonial empire in North America. Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821, and permanent Hispano agricultural communities spread north from Taos into the southern part of the Valley. This land became part of the United States following the Mexican-American War, which ended in 1848 with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Although the treaty included guarantees to protect the rights and property of residents who “watched the border cross them” as Mexico ceded territory, it quickly became apparent to Hispano residents of the Valley that there would not be a smooth transition from Mexican to American administration. The treaty guaranteed residents of the region “the enjoyment of all the rights of citizens of the United States, according to the principles of the Constitution.” However, many of the Americans coming into the area did not embrace this commitment to equality. On November 9, 1866, shortly after the US Congress added the Valley to the recently created Colorado Territory, The Rocky Mountain News reflected many of the newcomers’ racist attitudes towards the Hispano settlements: “The counties of Conejos and Costilla are settled, principally, by New Mexicans, a mongrel race, half Spanish and half Indian.”

The Maestas children had to walk through dangerous rail crossings in Alamosa on their way to their newly assigned school.

In the face of such discrimination, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, many of the area’s Hispano residents banded together to create mutual aid societies. With support from their communities, they fought against discriminatory attitudes toward wage laborers, resisted illegal and immoral actions by land barons, and stood up to acquisitive mine owners and the railroad operators. One group in particular, La Sociedad Protección Mutua de Trabajadores Unidos (SPMDTU), founded in 1900 in the town of Antonito about thirty miles south of Alamosa, became (and continues to be) a force for community support in the Valley.

The communities of the Valley quickly realized how important that support would be. In 1908, the Alamosa School board purchased land on the south side of town, on “the Mexican side of the tracks,” to build a “Mexican school.” The initial idea for the school was to provide language support for Spanish-speaking students before assimilating them into an English language school. That intention, however genuine, was soon abandoned, and the district enacted a new policy under which all students with Spanish surnames were compelled to attend the school for Hispano students, regardless of their English proficiency.

Many of those experiencing this discrimination were American citizens and felt that their rights were being violated. Some parents attempted to enroll their children in the English speaking schools despite the policy. When denied, the outraged parents organized as a collective voice calling themselves the Spanish American Union. This support organization drafted a resolution to challenge their exclusion and argued the school was discriminating based on race, not language. They took their challenge to the Alamosa School Board of Education, but were rebuffed and turned away. When they appealed to the Alamosa school district superintendent, George H. Shone, they were denied again. They then appealed to the Colorado State Board of Education, and to the Colorado State Superintendent of Public Instruction, who were unable or unwilling to address the issue.

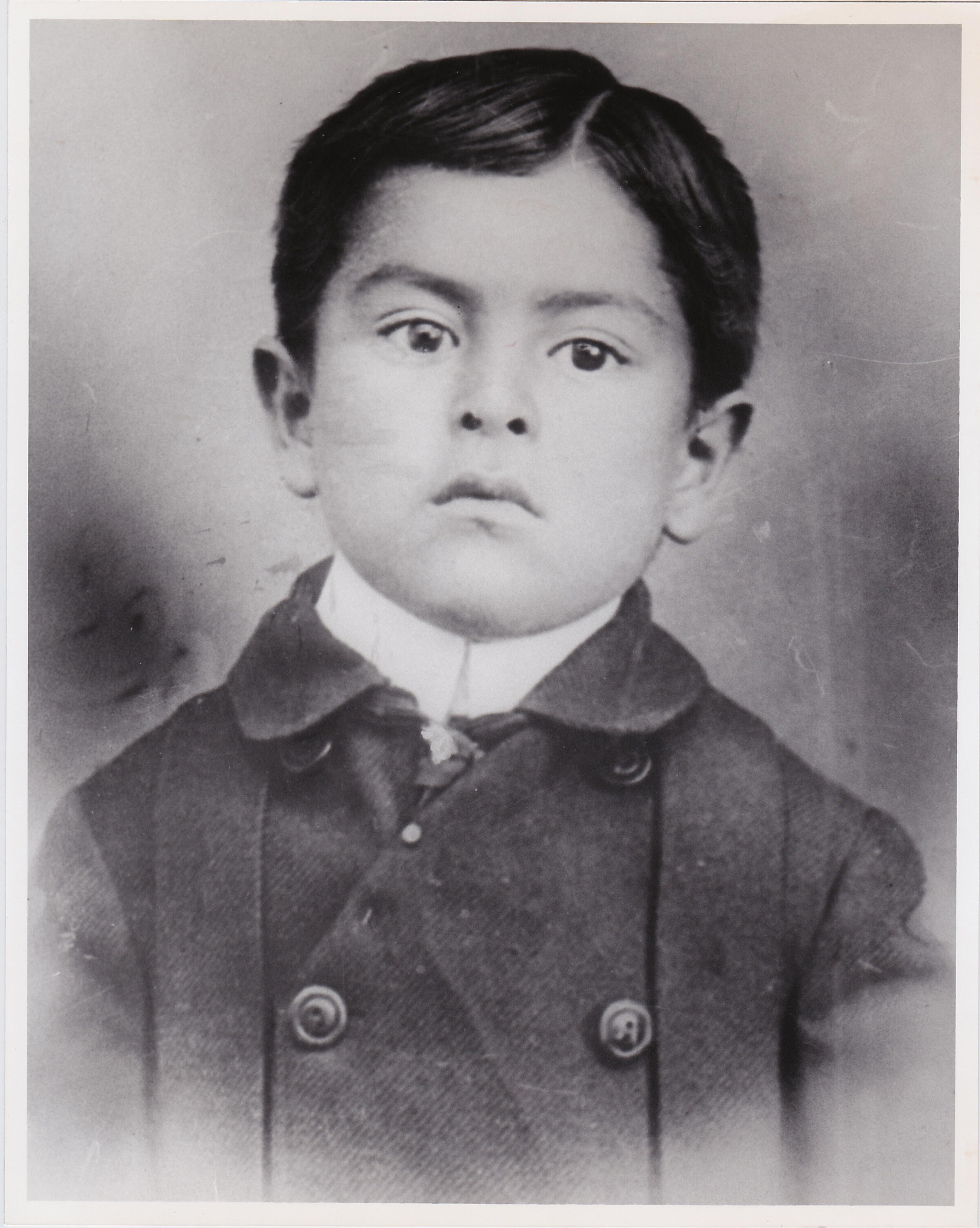

Miguel Maestas, one of the children at the center of the suit.

The parents, in hopes of showing their determination, pulled their students from the school in a boycott. In spite of the protest, the Alamosa School Board of Education still wouldn’t budge, and went so far as to accuse the parents of neglecting their children's education. Members of the Spanish American Union had previously consulted local lawyers, who advised them not to take the case to court as it would be too expensive and would not stand a chance of winning, even if they could find a lawyer to accept the case.

Becoming more desperate, Alamosa’s Hispano parents formed a second committee focused on raising money to secure legal counsel. A member of this committee, a Catholic priest named Father Montell, suggested a young lawyer in Denver, Raymond Sullivan, who agreed to represent the Hispano families.

Sullivan filed suit in 1913 on behalf of several Hispano families, but Francisco Maestas was the lead plaintiff. The injustice his young son Miguel faced was particularly acute: He had to walk past the English-speaking North Side School on his way to the Spanish language school, crossing several dangerous railroad tracks along the way. Sullivan argued in court that, in denying the children access to the closest school, school officials were making a “distinction and classification of pupils in the public schools on account of race or color contrary to Article IX, Section 8 of the Colorado Constitution.” This article stated (then as now) that “no sectarian tenets or doctrines shall ever be taught in the public schools, nor shall any distinction and classification of pupils be made on account of race or color.” Sullivan asked the court to order that the district “admit the said child of plaintiff to the North Side School or the most convenient of the public schools of said city to which he has the right of admission without any distinction or classification on account of his race or color.”

Countering Sullivan and the SPMDTU claim, the Alamosa School Board argued that Miguel Maestas and other Mexican American children were not being discriminated against because of their race, proposing that the Hispano children were in fact “Caucasian.” Lawyers defending the school district argued that the children needed to attend a Spanish language school because they were deficient in English. But Raymond Sullivan saw through this ploy. Contesting their characterization of the childrens’ language proficiency, he had the children testify in court. The court provided an interpreter for the children, but the children proved that they didn’t need one by answering every question in English before the translator started speaking.

Raymond S. Sullivan filed suit in 1913 on behalf of several Hispano families, including the Maestas.

District Court Judge Charles Holbrook ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in 1914: “In the opinion of the court … the only way to destroy this feeling of discontent and bitterness which has recently grown up, is to allow all children so prepared, to attend the school nearest them.”

The Hispano families of Alamosa were vindicated and victorious. But victory didn’t bring an end to discrimination. Struggles continued, and the Maestas decision, which the school board did not appeal, faded from memory. Even the school board lost all records of the case. In fact, the case was so forgotten that it was not cited in future cases of a similar nature. Nearly six more decades would pass before Keyes v. School District 1 in Denver reaffirmed that segregation was illegal in Colorado schools—a decision that did not even reference the Maestas or their victory in the Valley.

Nearly a century after the Maestas case was decided, Dr. Gonzalo Guzmán, a professor of educational studies at Macalester College in Minnesota, came across a reference to it in an archived newspaper. He was stunned that the Maestas case wasn’t more widely known, so he reached out to colleagues Dr. Rubén Donato, an educational historian at the University of Colorado Boulder, and Dr. Jarod Hanson, a former lawyer and senior instructor at the University of Colorado Denver. They contacted Colorado’s 12th District Court Judge Martín Gonzales, who found the original court documents. Together, the group began researching and writing, and in 2017, the professors published their findings in the Journal of Latinos in Education.

The published paper was a great accomplishment, offering a foundation to build upon as scholars continue studying how Southern Colorado communities successfully asserted their rights in the early twentieth century. But the story still isn’t as well known in the community of Alamosa or in the greater San Luis Valley as one might expect for a legal precedent of such significance. To spread greater awareness about this significant moment in Colorado history, Judge Gonzales organized the Maestas Commemoration Committee, which includes academics, descendants of the Maestas family, members of the still-active SPMDTU, and Alamosa community members.

Artist Reynaldo “Sonny” Rivera poses with his bronze sculpture commemorating the 1914 victory over school segregation. The relief was created to hang in the Alamosa Municipal Courthouse in 2022.

Efforts at commemoration and public awareness are ongoing. A traveling exhibition commemorating the Maestas case began a tour of Colorado at the Capitol building, and will be on display in History Colorado’s museums and on university campuses throughout 2022 and 2023. Additionally, a community celebration will take place on October 1 this year in Alamosa, where a life-sized bronze relief honoring the case will be permanently installed in the courthouse’s entrance.

Though they didn’t know it at the time, the Maestas family and those involved with the suit were setting an early precedent for educational justice. The almost-forgotten case that started just over 100 years ago as a local group fighting for their children stands today as a lesson in the fickleness of public memory and a reminder of the long crusade for racial equality in Colorado. In many ways this movement is still ongoing. It would have been easier for the Maestas family to simply buckle in the face of overwhelming systemic inequity. But like so many others since Francisco and Miguel Maestas crossed those dangerous train tracks in Alamosa, the family fought for their rights and won.

Let it be a reminder to us all to never give up the fight.

Author and artist Katie Dokson created this mural to commemorate the Maestas decision in 2021.

For Further Exploration

To learn more about the history and exhibit locations at www.maestascase.com and check out news coverage about commemoration efforts from Rocky Mountain PBS.