Story

Building Camp Hale: A Deeper History of America’s High-Altitude Army Training Ground

The Pando Constructors built Camp Hale with extraordinary speed. Their unsung contributions to America’s war effort set the stage for the 10th Mountain Division’s heroism during World War II.

High in the Colorado Rockies, between Minturn and Leadville on US Highway 24, there sits a flat, open valley, some three miles long and nearly a mile wide. History buffs and regular high-country travelers might know that this was the site of Camp Hale, the World War II training camp for the 14,000-man 10th Mountain Division.

Faded Forest Service interpretive signs in the area show the camp in its glory in 1943—a thousand white buildings that housed the only American military unit specifically trained for mountain and winter warfare. Camp Hale, which was named for Brigadier General Irving Hale, born and raised in Denver and commander of the Colorado regiment that captured Manila during the Spanish-American War, is Colorado’s most famous military unit. Generations of Colorado skiers have thanked the veterans who returned to Colorado to start the ski areas of Aspen, Vail, and Arapahoe Basin.

But there’s more to the story of Camp Hale. In fact, the deeper history of what could have been the birthplace of modern Colorado’s booming ski industry is relatively unknown because the people who built it—the Pando Constructors—have been overlooked. With President Joe Biden set to designate Camp Hale as a national monument in late 2022, the incredible work of the Pando Constructors is more relevant and important than ever before.

Camp Hale’s story began in 1940, before Pearl Harbor thrust the US into World War II, when three East Coast ski enthusiasts—Charles Minot Dole, Roger Langley, and Roland Palmedo (who, in 1936, combined to create the National Ski Patrol System, with Dole as its president)—were worried about how unprepared America was to become embroiled in the war that had just started in Europe. More specifically, the trio was concerned that the US Army would not be able to effectively fight and survive in Europe’s harsh alpine regions.

Their efforts to alert the Army to their fears were initially met with official indifference, but as the US became more involved with the international war effort, plans were made to create a unit capable of countering Germany’s mountain troops. Several sites around the country were evaluated as a site for a potential training camp, but the one that met all the criteria was a place in Colorado known as the Pando Valley. Sitting at an elevation of 9,250 feet, the area had the high altitude necessary to acclimate the troops. The valley’s steep cliffs and an annual snowfall of 250 inches made it the ideal training ground. It was 100 miles west of Denver, so it was remote, yet accessible by road and the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad. Plus the mining town of Leadville was only twenty miles away.

In October 1941, the Army authorized the Dole-Langley-Palmedo trio to begin recruiting skiers, mountaineers, and outdoorsmen to what became known as the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment, forerunner to the 10th Mountain Division. Its members began training on Mount Rainier, near Seattle, Washington, while construction started at the Colorado site.

Moving with incredible wartime swiftness, by the end of March 1942, the Army had authorized construction. The initial budget was five million dollars, but the cost would balloon to thirty million by the time the project was completed. Declaring eminent domain, the land for the camp and its artillery range was purchased by the government from local property owners, who at that time consisted mostly of ranchers.

Over 10,000 men—mostly men beyond draft age and others who were otherwise exempt from the draft— became the workers for an organization known as Pando Constructors. With no adequate housing nearby that could hold such a large army of workers, the men first had to build their own barracks—eighty-eight of them.

Construction began in April 1942,—an extraordinary feat that has largely gone unheralded until now. By the middle of 1942, the mostly forgotten Pando Constructors workmen had finished their temporary camp and had concurrently begun work on the military cantonment area. It was now time to finish what they had started back in April: the main camp.

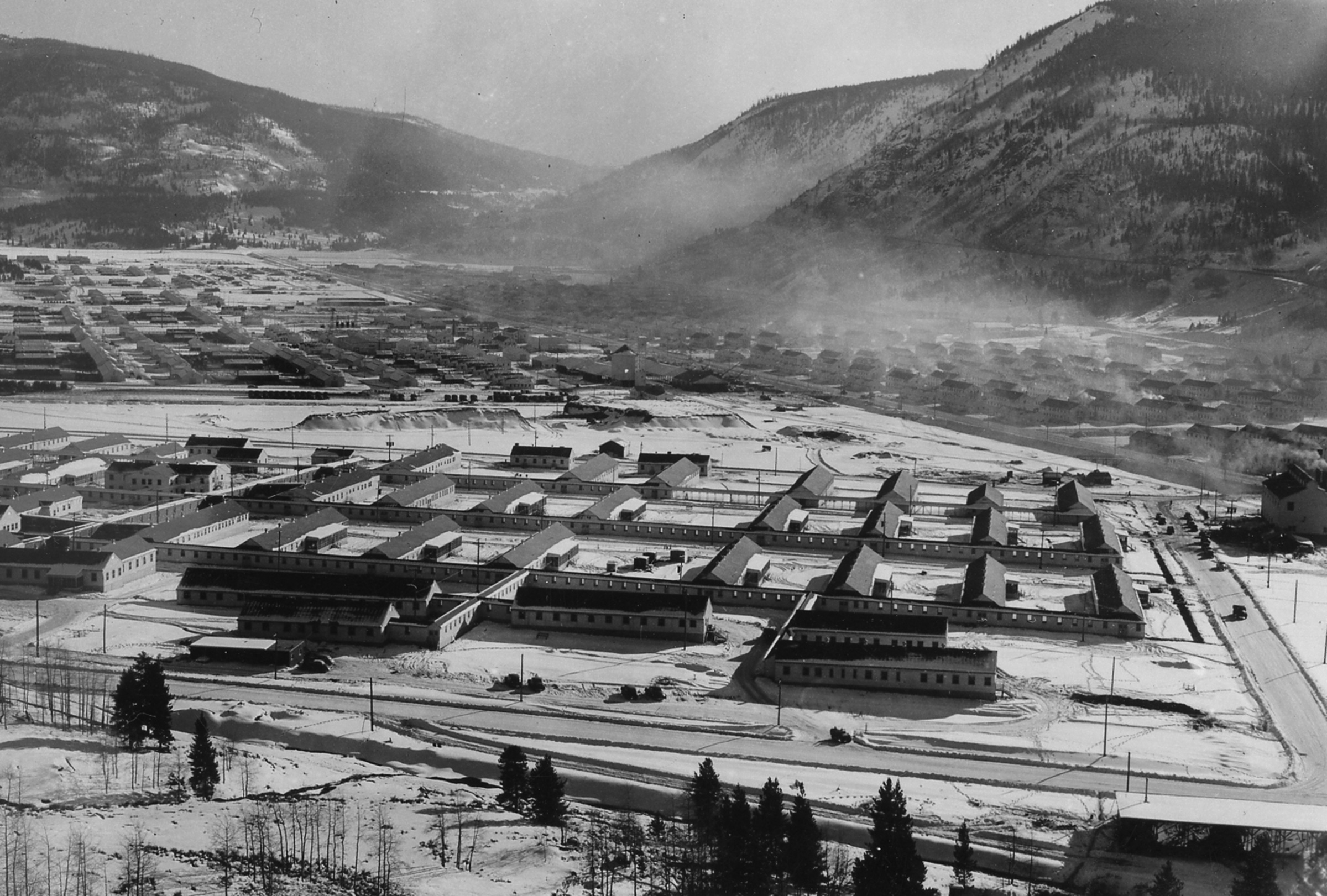

Built in just seven months were 226 barracks, thirty-three administration buildings, a 676-bed hospital, a veterinarian hospital for horses, mules, and dogs, five churches and chapels, 100 mess halls, a bakery, three theaters, one field house, indoor pistol ranges, seven post exchanges, two service clubs, one officers club, horse and mule barns, grain storage, coal storage, numerous warehouses, a stockade, vehicle-maintenance facilities, weapons ranges, six underground ammunition magazines, four water storage tanks, three fire stations, a school, post office, medical and dental clinics, a combat village, two ski areas, and much more. It was an amazing feat of wartime construction that has largely been overshadowed by the heroics and sacrifices of the soldiers who trained at what was essentially a small city built high in the Rocky Mountains.

The photos that follow track the amazing history of how this instant city came to be, and the incredible accomplishments of the Pando Constructors who made it possible to train America’s mountain troops here in Colorado

A pictorial history of Camp Hale, titled 10th Mountain Division at Camp Hale and authored by Flint Whitlock and Eric Miller, will be published in early 2023 by Arcadia Publishing Company. The majority of the images come from the photographic collections of the Denver Public Library. Check out History Colorado’s unique collection of 10th Mountain Division artifacts online!

In April 1942, the Pando Valley was empty, but a flurry of construction was about to begin. With the war on, and America’s military draft gobbling up almost every able-bodied man, finding thousands of construction workers to build Camp Hale was an outstanding effort in itself.

Here, a bulldozer clears foliage from the valley floor. Much of the work, however, had to be done by hand.

Heavy equipment was necessary to widen, deepen, and straighten the Eagle River that ran through the site.

Millions of cubic yards of dirt had to be brought in to level the site. Here, a Caterpillar road grader smoothes the ground in preparation for the construction of the buildings.

Workers nail together one of the eighty-eight barracks at the Pando Constructors’ camp. In addition to the workers’ camp that was designed to hold 8,000 men, another 2,800 lived off-site in trailers and homes that had been boarded up for years in Leadville, Minturn, and Red Cliff.

Workers lay out planks for a large building. The temporary camp for the Pando Constructors workers is visible in the distance behind the trees.

A carpenter cuts a board to length. In order to meet the deadline, work went on six and sometimes seven days a week. Attention to detail and craftsmanship were important to Pando Constructors. Although the November 1942 deadline loomed, there is no indication that any shortcuts were taken by the builders.

Two workmen hammer together one of the buildings. One day in August 1942, sixty-one carpenters and four shinglers set out to build a complete sixty-three-man barracks building in record time. They did—in seven hours and forty-five minutes, breaking the old national record by more than three hours!

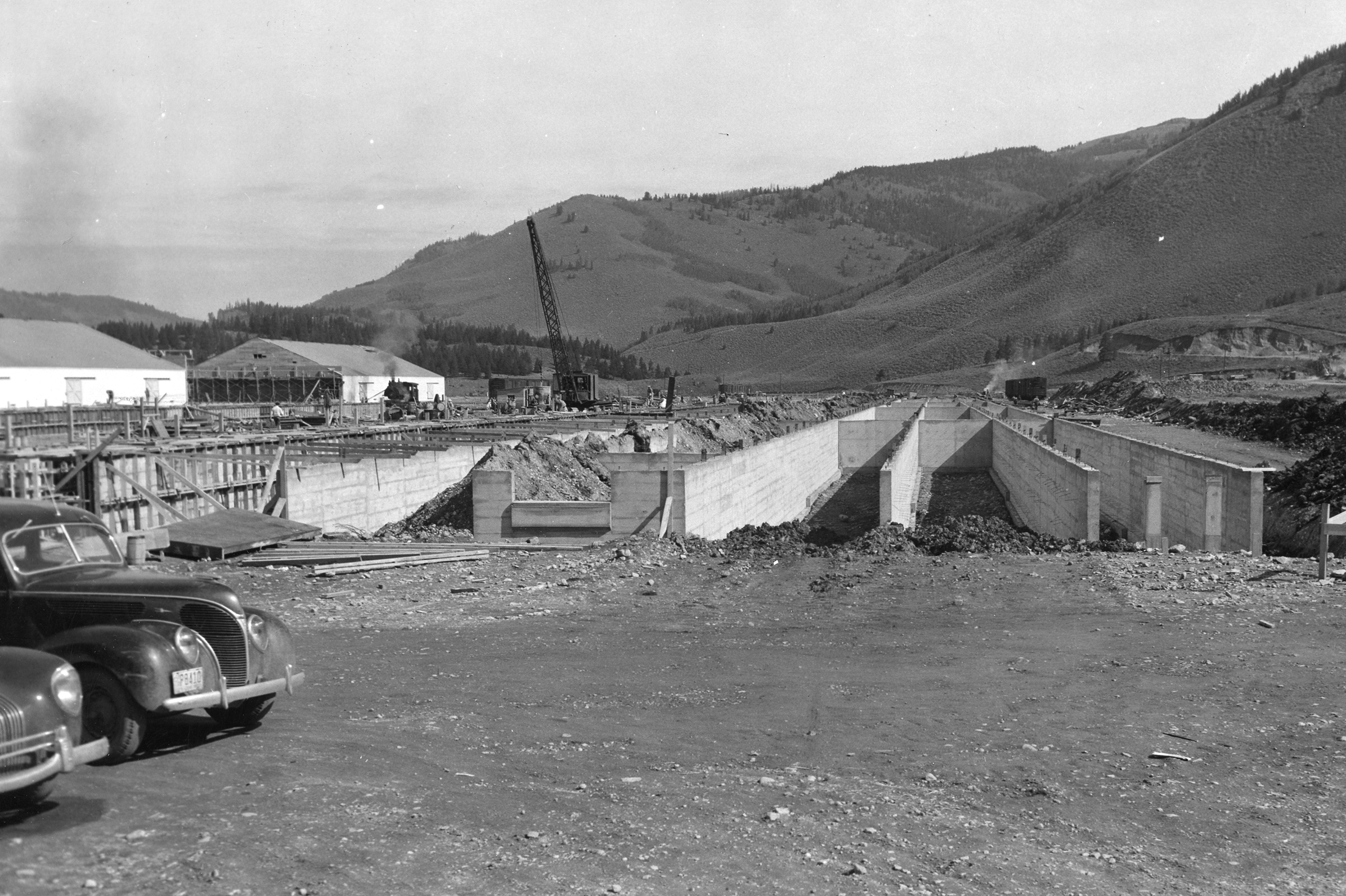

The concrete foundations for three immense buildings in the warehouse area on the north end of the camp have been laid and await the finishing touches—floors, walls, roofs, and more.

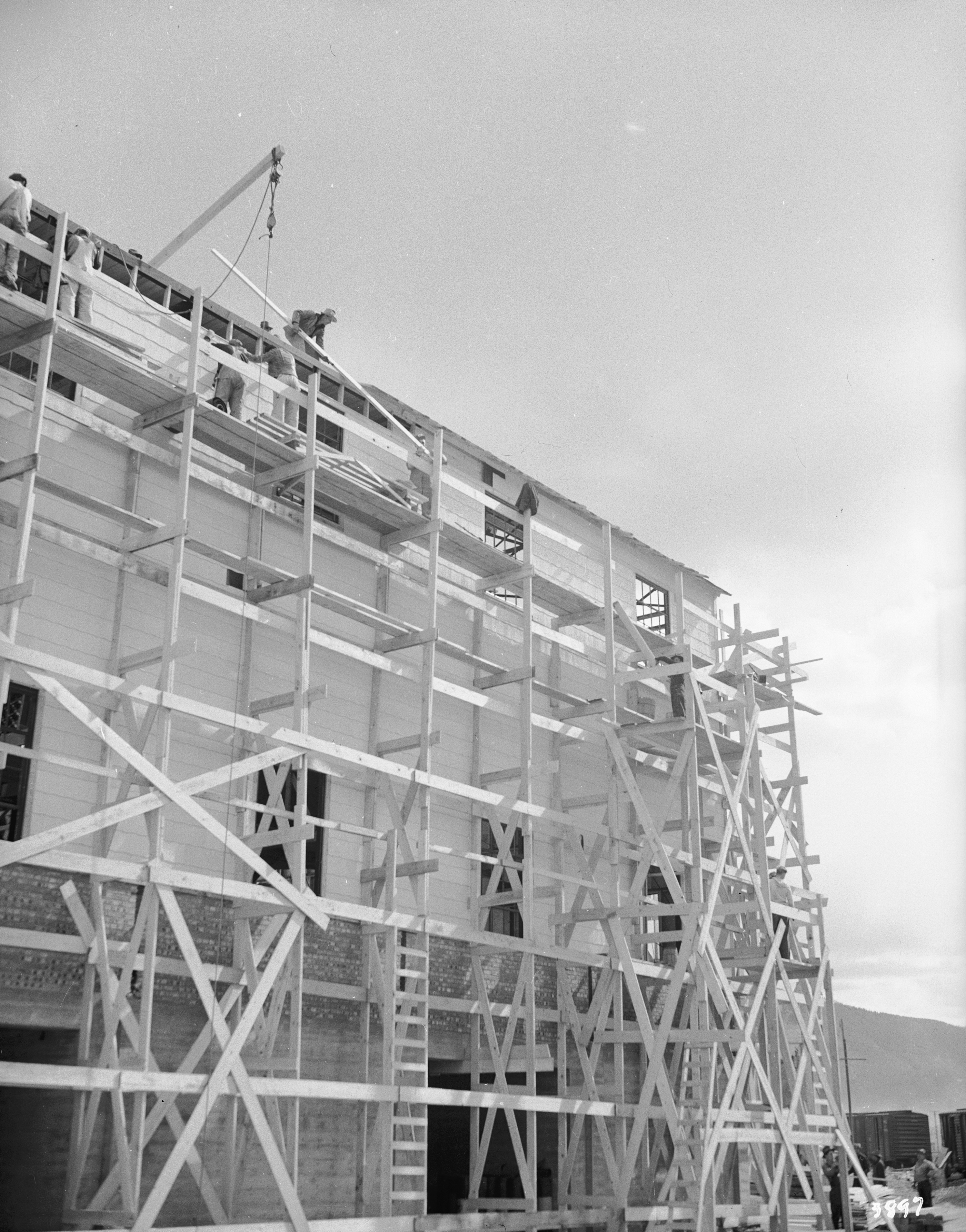

Scaffolding rises on the exterior of a three-story building. Millions of board feet of lumber were used in the construction of the camp.

The Pando Valley hummed with non-stop construction activity for seven months. Here, a lumber truck delivers boards to a building in the hospital area.

In March 1943, Warner Bros. Pictures was contracted by the US Army to make a twenty-minute recruiting film for the mountain troops titled Mountain Fighters. Here, a cameraman (left, foreground) operates a camera wrapped in a blanket (to protect it from the cold) while a soundman (right) holds a boom microphone above an actor speaking his lines.

Dressed in ski parkas tucked into their trousers, and carrying skis and rucksacks, the mountain troops march through the streets of Camp Hale. This photo was taken during the filming of Mountain Fighters.

A 240-woman WAC detachment (Women’s Army Corps) arrived at Camp Hale on May 27, 1943. They were motor pool drivers and mechanics, supply specialists, secretaries, and worked in communications and accounting. Their barracks were at First and B Streets.

A high-angle view of the 676-bed Camp Hale hospital complex located at the north end of the valley shows enclosed walkways connecting the various hospital wards. Also visible is a pall of smoke drifting over the camp—a major health concern. Many soldiers came down with a lung condition the men dubbed the “Pando Hack,” and some needed to be transferred out of the division because of it.

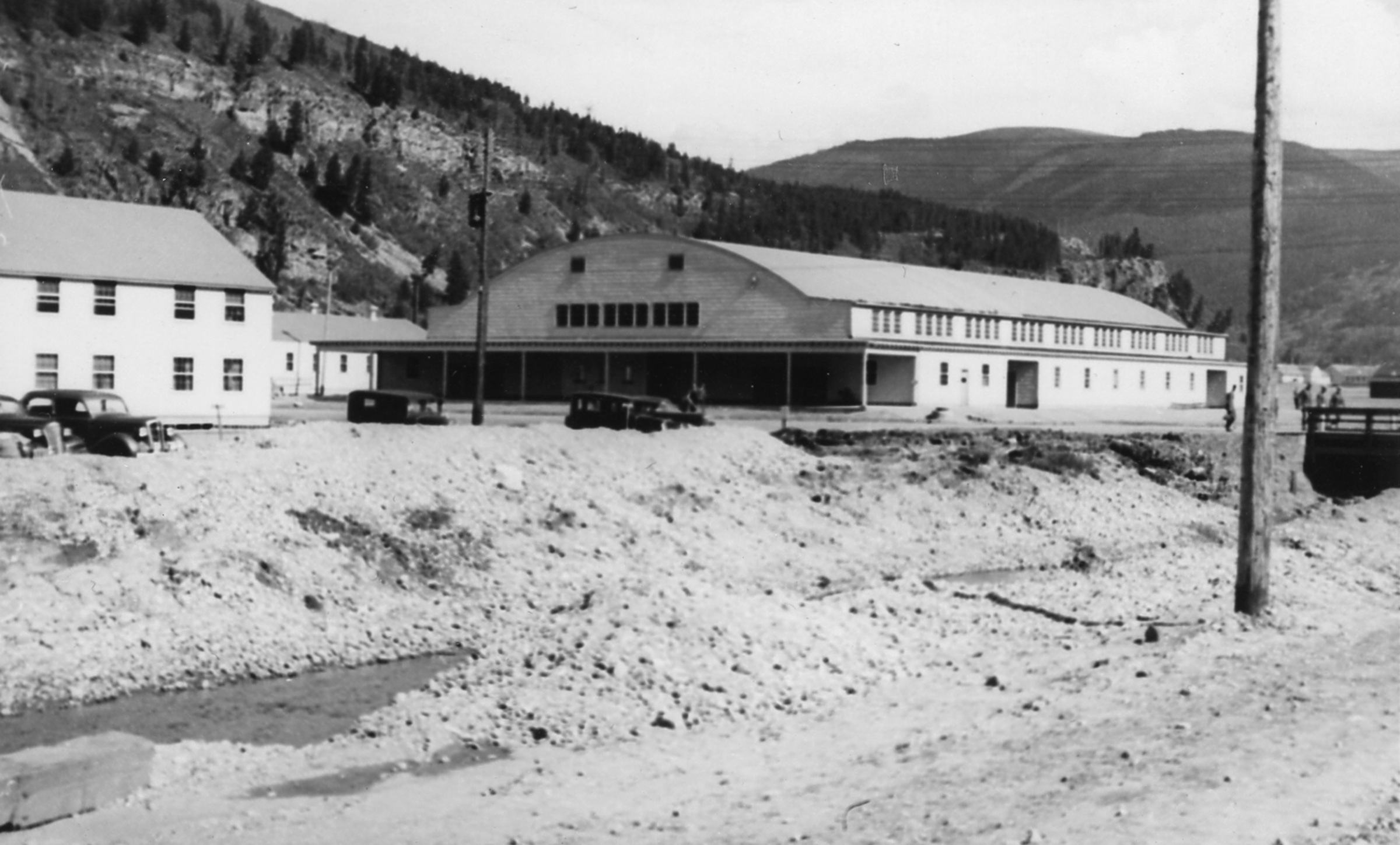

The largest building at Camp Hale—the 18,000-square-foot field house—was the scene of ceremonies, basketball and volleyball games, exhibition boxing matches (world heavyweight champion Joe Louis once staged an exhibition here), concerts, and dances. The concrete remains of the field house can still be seen today.

Besides being the highest military post in the nation, Camp Hale was one of the most scenic. This view is from the north, looking south.

In April 1945, snow was still on the ground when Theater No. 2 was taken apart piece by piece by a group of 3,500 German prisoners of war, held in over forty POW camps in Colorado; they were paid eighty cents a day for their labors. Soon, the camp that over 10,000 workers spent seven months building at a cost of thirty million dollars had ceased to exist.