Story

Collecting Colorado

The work of a nineteenth-century botanist is helping us understand today’s rapidly changing landscape.

As his west-bound train crossed the Colorado border, the twenty-six-year-old teacher from Iowa recognized that his long journey across the prairies was nearing its end. He sat in the rumbling coach, his eyes probably scanning the horizon for the first glimpse of the mountains that lay ahead. It was May 1, 1878, just a few weeks after he received a master’s degree from Iowa College and concluded the Latin classes he had been teaching, and not quite two years since Colorado had become the Centennial State. For Marcus Eugene Jones, the first of two life-changing summers in the Front Range of Colorado’s Southern Rocky Mountains had just begun. By the time they were over, Jones would have assembled a record of the region’s plant life that continues to allow scientists to study the Western ecosystem and how it is changing.

Born in northeastern Ohio in 1852 as the oldest child in a farm family, Jones was raised in humble circumstances and with a love of nature, especially for plant life. When he was barely into his teens his family moved to a small farm near Grinnell, in central Iowa, where Jones worked the fields beside his brothers and helped his father run a sawmill. After attending a local academy, Jones entered Iowa [now Grinnell] College with its classical curriculum. Because he excelled at Latin, Jones began to anticipate becoming either a Latin teacher or a school principal, occupations his two degrees prepared him for.

While Caesar and Cicero occupied his academic world, Jones also found time to indulge his interest in nature by reading texts on botany and geology. In his college and graduate school days he began to wander nearby fields to gather plant specimens, both for his own collection and to sell to schools and museums, and to professional botanists and amateur collectors who shared his appreciation for this popular scientific hobby. Exhausting Iowa’s botanical offerings, Jones began to ponder a search for new areas to explore, and before long he determined upon a location that would combine his twin interests in geology and botany: the newly-created state of Colorado.

Colorado beckoned for other reasons as well. Jones began to realize that a life as a Latin teacher no longer had the same appeal, and he may have been looking for an outdoor adventure after spending seven years in the classroom. Colorado was experiencing a tourist boom now that railroad connections had made the scenic beauty of the state accessible to Eastern visitors. Jones was plagued by headaches, and he may have reasoned that Colorado’s invigorating climate would provide a cure. Jones also planned to write a narrative of his explorations, an exercise he looked forward to with relish. So, prepared for a combination of scientific excursion, wilderness adventure, journey for health, and journalistic exercise—and having no commitments for the next several months—Jones set off for the Rocky Mountains.

Colorado was a place in transition. Jones wrote of his anticipation of seeing bison herds rumble across the plains, although he certainly knew that the days of such sights had long passed. What had not changed about Colorado was its magnificent landscape. It was the promise of seeing long-awaited mountains that kept Jones alert as the train chugged toward Pueblo. As they got closer, Jones and his fellow passengers climbed onto outside running boards, braving the elements and the shower of ashes from the locomotive as they stared in vain in the direction of cloud-covered Pikes Peak. Disappointed at missing this landmark, Jones soon consoled himself when the Spanish Peaks and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains came into view.

At Pueblo, Jones switched trains to the narrow-gauge Denver & Rio Grande Railway for the ride to Colorado Springs and the end of his 800-mile journey. Although thrilled with the mountains looming overhead, the Midwesterner felt some disappointment with the plant life he observed, writing of the “naked and devastated soil of the plains.” Colorado Springs, a carefully designed new city of 4,200 people, boasted exclusive resort hotels, sanatoria for tuberculosis patients, parks, newspapers, churches, and libraries. Avoiding the tourist facilities, Jones made his way to the home of friends from Grinnell. It was from this house that he set off on his first solitary hike into the wilderness, crossing the cold swift current of Fountain Creek (known then as Fontaine qui Bouille, a holdover from the days when French trappers were re-inscribing the landscape with non-Indigenous names) and heading west into Cheyenne Canyon.

Traveling without companion or map, Jones was delighted to soon find appealing samples of Colorado plant life, such as pasque flower (Pulsatilla patens), bear’s grape (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) and Fendler’s false-cloak fern (Argyrochosma fendleri). As the day progressed, the cylindrical specimen case, or vasculum, which Jones slung over his shoulder, was beginning to fill, and he realized that he had greatly underestimated the distance he had walked. An early May snowstorm surprised him as he trod along mesas which soared above the 6,000-foot altitude of Colorado Springs, a mile higher than the elevation of his Iowa home, and he marveled at the pinkish-red alpenglow that momentarily lit the peaks at sundown.

With darkness falling and his energy waning, Jones suddenly found himself trapped at the top of a twenty-five-foot waterfall with no way to go except straight down. Tentatively feeling for hand- and toe-holds in the cliff face, he took the only available option, which was inching his way down the slippery rocks and losing his knapsack and vasculum to the force of gravity along the way. Completing the treacherous descent, Jones eventually arrived at the bottom, wet and muddy, battered and bruised, tired and hungry, but exhilarated by the adventure and eager to explore more of Colorado’s natural offerings.

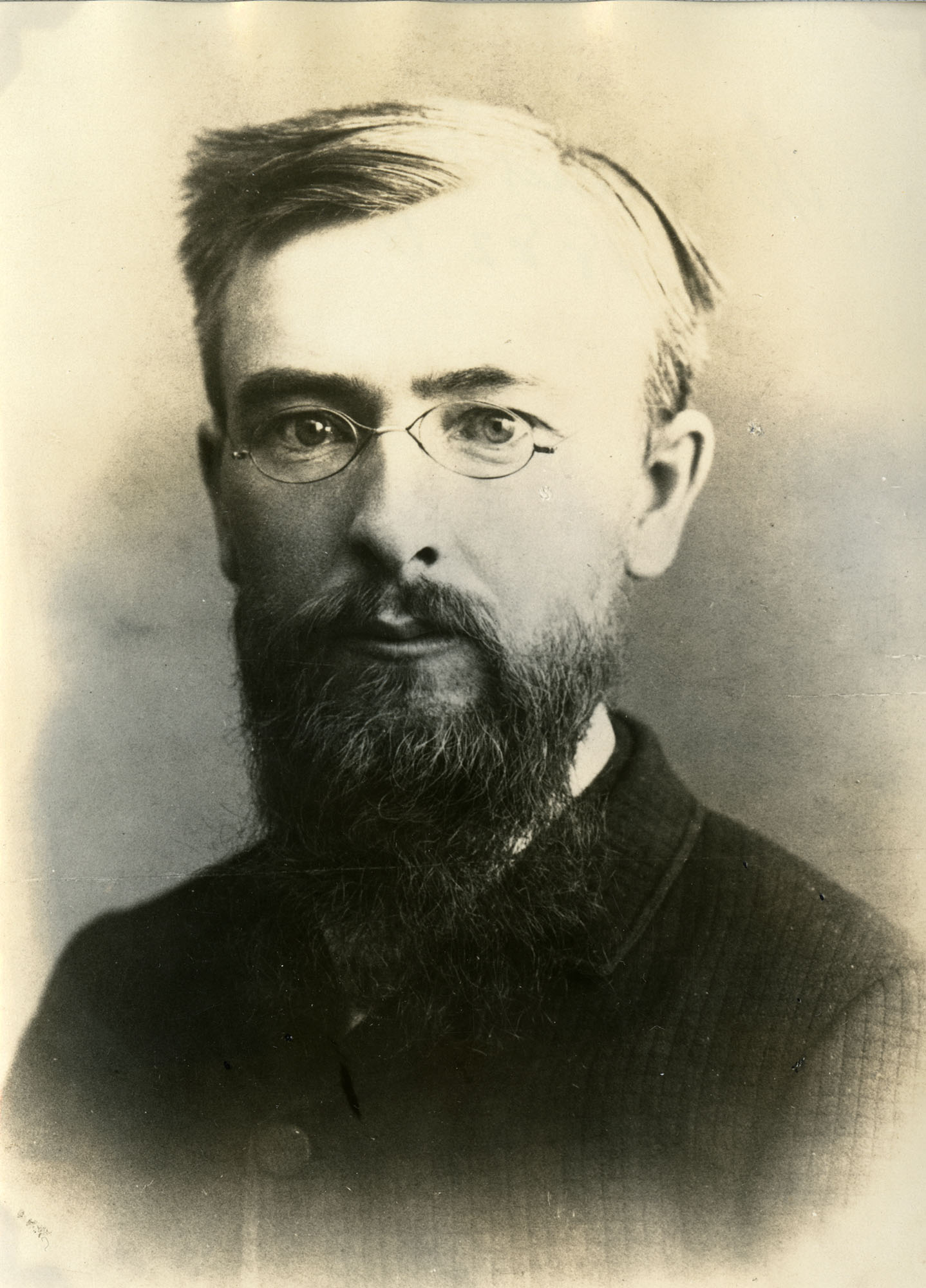

Marcus Eugene Jones in 1882 at age thirty, four years after earning his degree and boarding a train bound for Colorado.

Indigenous peoples had been studying Colorado’s flora and fauna since time immemorial. And Jones knew from his studies that European and American botanists had identified more than 3,300 species of plants in Colorado, including ferns, grasses, wildflowers, shrubs, and trees, many of them unique to their locales. So, he was far from the first botanist to investigate the state’s flora, and he probably did not expect to find varieties unknown to Western science. However, Jones did hope to gather examples of as many of the species as possible and to find some in places where they had not previously been seen. He was not specializing in any particular plant species but was instead an omnivorous collector, motivated by his code to “never pass by a plant.”

With his appetite for exploring whetted by the Cheyenne Canyon excursion, Jones spent the next several weeks adventuring by horse and buckboard wagon in the Colorado Springs region, going first to Manitou Springs, which then proclaimed itself the “Saratoga of the West.” Although still suffering from aches and bruises from the scramble down the falls, he did not relax in one of the town’s curative warm baths or sample any of Manitou’s healing mineral waters. Throughout the summer, Jones did not participate in the pleasures and luxuries of the tourist locales, for he was not on vacation but on a scientific expedition (although one augmented by commercial endeavors). He was accumulating specimens to sell and also wholesaling albums of dried plants to a dealer in Denver.

Jones was excited at Manitou by finding a plant he had never seen before, an Indian milkvetch (Astragalus australis), an example of the botanical genus he would study throughout his life. Next came the rock formations of Glen Eyrie— “one of the most beautiful sites in the West,” thought Jones—and the magnificent vistas of the Garden of the Gods, where he indulged his love of geology by examining the colorful and spectacular sandstone and limestone mountainous structures of the site.

Denver beckoned next, or rather it was the countryside in that area, for Jones seems to have been fundamentally disinterested in cities: He ignored urban amenities throughout his trip, preferring instead to study unspoiled nature. On his way to the capital city, Jones experienced a terrifying thunderstorm as he passed through Palmer Divide, the point of separation of the Arkansas and South Platte River basins. On this northbound journey he also noticed how the change of latitude affected plant life. He found little of interest in the vegetation of Denver, agreeing with his contemporary Isabella Bird that the city was “brown and treeless upon the brown and treeless plain.”

Columbines (Aquilegia caerulea), the Colorado State flower, were one of the marvels of Colorado’s flora Jones collected in his western sojourns.

As soon as he could, Jones headed west through Clear Creek Canyon past Golden toward the “Silver Queen” of Georgetown, a prosperous mining center with hotels and theaters, bakeries, jewelry stores, and an ice cream parlor—none of which appealed to him. He did find Georgetown to be a fertile ground for producing botanical specimens, although he was also greatly distressed by the environmental destruction that mining and smelting were causing in the area.

Pressing westward, Jones traveled through Argentine Pass toward the Continental Divide, passing numerous mining towns and pausing to climb Grays Peak, a mountain the new settlers named for Asa Gray, the most prominent botanist of Jones’s era. Gray, a professor at Harvard College, was one of the experts Jones consulted in the quest to identify plants he had collected during his Colorado summer. (In this era botanists frequently exchanged specimens and assisted one another to determine the identities of plants in a collaborative effort to advance botanical knowledge.)

The trek up Grays Peak took Jones through forests of firs and pines followed by fields of colorful flowers—Rocky Mountain columbines (Aquilegia caerulea), longfleaf phlox (Phlox longifolia), and Alpine bluebells (Mertensia tweedyi)—along a zigzag path until he reached the treeless summit at 14,278 feet atop the Continental Divide. He noted how plant life changed markedly as he emerged from one zone of altitude into the next. From this clear spot Jones stared in awe at the landscape that lay below him, marveling that “the vastness of the country, seen from this height, is really indescribable.”

Jones preferred to explore Colorado alone, facing the challenges and the quiet— “all nature seemed awed into perpetual silence in these mountains”—of the state. On his travels in the mountains he often lived off the land, enjoying meals of prairie chickens and hares. Focused on his botanical collecting, Jones worked long hours daily, although he never worked on Sundays when he attended worship services if he could locate a nearby church. He needed no recreation and avoided social gatherings on this trip, although he was by nature a quick-witted, garrulous man who enjoyed verbal sparring and could be contentious at times.

Descending Mount Gray, Jones ambled into the open stretches of South Park passing by Fairplay where a blustery September snowstorm surprised him. Along the way, Jones found prime samples of big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata), an aromatic plant which provides food and cover for birds and animals. The cold weather stymied his collecting plans by ending the season’s plant growth. Continuing on this loop Jones passed by Cañon City and made his way back to Pueblo, where he caught the train for the long ride back to Iowa.

Now began the work of classifying the specimens he had obtained in Colorado, writing accounts of his explorations there, and preparing sets of preserved plants for sale. From the penciled annotations and markings in his personal copy of Porter and Coulter’s 1874 Synopsis of the Flora of Colorado, it is apparent that Jones relied heavily on the work of botanists who had preceded him. Additionally, when he encountered plants he was unable to identify, Jones requested the aid of experienced botanists, sending specimens to them and usually receiving helpful replies by return mail. In promotional literature for the plant sets he was selling—priced at $50 for a complete set of 800 or ten cents apiece—Jones also cited these older colleagues as authorities supporting the accuracy of his descriptions.

After a winter of study, Jones determined that he had gathered examples of 1,100 plant species during his Colorado summer, during which he had traveled about 10 percent of the state’s area. This season of reflection also gave him time to reminisce about “the beauty of Argentine Gorge [Pass], the grandeur of Mount Lincoln, the majesty of Grays Peak, and the sublimity of the region,” and to begin preparation for an article that would eventually appear in a horticultural journal. For Jones, this daily scrutiny of the plant specimens and the chance to write about them in detail surely intensified his interest in botany and prompted him to return to Colorado again the following summer.

In the spring of 1879 Jones was serving as a fill-in botany instructor in Grinnell when he received an offer to take a similar position for the summer at Colorado College, then only four years old. No sooner did he conclude the term at Iowa College than he boarded the train for a return to the Rockies, traveling lightly; the frugal Jones was able to make a meal out of a lemon, a pack of crackers, and a cup of coffee, all for twenty-five cents. On May 17, he arrived in Colorado Springs, spent two days in preparation for his classes, and began to teach a general botany class and a second entitled “How Plants Grow.”

In Cheyenne Canyon, scene of the previous summer’s losing encounter with the waterfall, Jones was excited to find several examples of fungus such as rusts and smuts, then considered to belong to the plant kingdom and thus fair game for a botanist. He spotted examples of grasses near Manitou, a fine sky-blue larkspur (Delphinium azureum) along the Bear River, and a silvery lupine (Lupinus argenteus) near Colorado Springs. In Glen Eyrie, a spot he had admired so much for its rock formations the year before, Jones enjoyed snacking on pinyon pine nuts, and beside a stream he was surprised to find an odorless carrion flower (Smilax herbacea), a plant so called because of its corpse-like smell. In his off hours from teaching Jones busied himself assembling souvenir packets of dried plants, and he made a specific search for loco weed (species of Oxytropis or Astragalus), and other poisonous plants which are dangerous to livestock.

In contrast to his solitary explorations of the previous summer, in 1879 Jones participated in several outings with colleagues and students from the college. One of these was to the popular tourist destination of Monument Park north of Colorado Springs where the group camped overnight, Jones apparently finding few plant specimens, or anything else, to interest him. “Monument Park is a humbug”—Jones-speak and common slang of the period for a fraud or a sham, reads the entry in his diary for the day of the visit.

An 1886 lithograph depicting what Pikes Peak and Colorado City, which later became part of Colorado Springs. Jones found the mountains and red rock formations stunning, but was even more taken with the region’s diversity of plant life.

Ever since he first caught sight of Pikes Peak on his first day in Colorado in 1878, Jones was transfixed by the towering formation which he referred to variously as “the old grizzled monarch of the plains” or “the grand old mountain.” He seemed to feel the pink granite dome of the peak beckon to him, so finally, on June 27 of his second summer in the Rockies, Jones, accompanied by a fellow botany enthusiast and an experienced guide, began the ascent. Mounting burros, the group set off in the late afternoon to avoid the heat of the day and in hopes of timing their arrival at the mountaintop for dawn. Jones wondered at first about the slow pace of the burros, but soon reasoned that the diminutive but sturdy animals needed to conserve their strength for the long climb that lay ahead.

Jones enjoyed the antics of the inhabitants of a prairie dog town, marveled at the twisting trail that led them through canyons, across streams, and over mesas, and was smitten by the color changes in the sky as dusk approached. He was awe-struck by the expansive views of the landscape that lay below him just before dark, and before long was transfixed by the light from a glowing moon and twinkling stars “set out like diamonds.” Despite the cooling drop in temperature, a growing thirst and hunger, and the realization that burros did not provide the most comfortable seats, Jones was eager to press on despite the guide’s call for a brief rest on the mountainside. And after an hour spent lying on spruce boughs before a blazing campfire, the group was back on the trail, eager to cover the remaining distance before daybreak. Abandoning their exhausted mounts, the trio slowly picked their way to the top and was rewarded with the discovery that they were now above clouds turned red and gold by the rising sun. The view was spectacular, as was the clear crisp air of 14,259 feet above sea level.

After a brief visit to the US Army Signal Service weather station atop the mountain, the group began its descent with the increasing daylight giving Jones the chance to observe more plants than he had spotted on the way up. He was able to record alpine clover (Trifolium alpinum) and wooly thistles (Cirsium eriophorum), among others, all thriving in open meadows located above the timberline. Thus, the trek up Pikes Peak combined two of Jones’s favorite activities: exploring the mountains and searching for plant specimens; and the adventure further cemented his desire to become a western botanist.

Over the next two weeks Jones finished his teaching duties at Colorado College, prepared specimens for shipment back to Iowa, and contemplated his plans for the remainder of the summer. He squeezed into the narrow gauge for a trip to Denver, transferring there to a west-bound train which took him across the unvarying plains of Wyoming. As his ride plunged southward into Utah, however, Jones had to marvel at the new landscape of narrow canyons and craggy peaks that formed his entrance into Salt Lake City, which would be his base for the next several weeks. Drawing upon his Colorado experiences, Jones explored eastward into the Wasatch Mountains, finding some familiar plants and some that were new to him.

After six busy weeks in Utah, Jones returned to Iowa to begin the task of classifying his summer’s haul of plants. He also began to work in earnest on a manuscript destined for publication in Belgium, a scholarly activity that enabled him to relive his adventures as a naturalist over the past two summers. This included such highlights as the exotic beauty of the Garden of the Gods and the spectacular view from the summit of Grays Peak. Dangerous situations came to mind too, such as the time in Argentine Pass when a broken harness caused his horse to buck, nearly overturning the wagon, or the hasty descent down the waterfall in Cheyenne Canyon. Above all in Jones’s memory was the magnificence of the overwhelming mountains and the thrill he had in climbing and exploring, as well as the excitement at finding unexpected plants as he roamed Colorado’s landscape.

As he analyzed examples of 1,100 species obtained during that second summer Jones also polished his travel account, completing it in late 1879 and sending it off to Liège, where it was translated into French and published as Une Excursion Botanique au Colorado et Dans le Far West (“le Far West” signifying Utah).

Jones’s account received faint praise in European journals, but only minimal attention from American press. Likely its appearance in French limited its appeal to an audience of general readers here. There is no copy of an English version of the manuscript of Une Excursion Botanique among Jones’s collected papers, and an English translation of the pamphlet was never issued in the United States. Today the French original is available in digital form on the Biodiversity Heritage Library website, and a translation can be found on the Library page of the website of California Botanic Garden.

Castilleja miniata, also known as prairie fire or Indian paintbrush, photographed here in autochrome by Clark Blickensderfer, was among the plants that captured Jones’s imagination.

Anna Richardson, a teacher who had also studied at Iowa College, assisted Jones as he studied and classified what he collected. Identifying and mounting samples of dried plants together led their friendship to deepen, with the result that this unconventional courtship led to their marriage in February 1880. Immediately the young couple took the westbound train to Utah for an equally unusual honeymoon of botanical exploration, which had to be cut short when Marcus was offered a position teaching science at an academy in Salt Lake City. When this temporary assignment turned into full-time employment, the Joneses decided to stay in Utah.

Having tasted the freedom of the free-ranging botanist, it did not take long for Jones to rebel against the daily grind of classroom teaching, and he soon left that position. Anna operated her own school, the Jones Kindergarten, and she took in boarders in the large house they rented, while Marcus earned income by continuing to sell botanical specimens and doing freelance writing. He also put his studies of geology to good use by working as a consultant to railroads, as a self-taught mining engineer, and as a partner in several small mining operations. The deeply religious Jones served several small congregations as a lay pastor, and for a short time he worked as a librarian. But primarily Jones continued his botanical explorations.

During the years that followed, Jones explored the remote corners of Utah, Nevada, Idaho, Montana, and Washington as well as in Texas, Arizona, California, and northern Mexico. Jones remained an active collector until his death in 1934.

Jones amassed a huge herbarium (a compilation of preserved plant specimens) of 100,000 specimens that he sold to California’s Pomona College in 1923, which led to his move to Claremont, near Los Angeles. The Jones Herbarium has been merged into the collection at California Botanic Garden (formerly Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden), and it contains numerous Colorado specimens from the 1878 and 1879 explorations. As a record of plant life from an earlier era, when industrialized resource extraction was just beginning to reshape parts of the West to power the industrialization of the nation’s economy, historic herbariums such as those Jones assembled, along with his writings precisely describing the ecosystems he encountered, today have become a resource for scientists seeking to peer back into the past and understand how climate change is having an impact on the natural world

Nuphar polysepala, or the great yellow pond-lily, captured by early color photography. Jones was enamored with the unique ecology of the West, but overlooked the connection between the flora and the native inhabitants for whom the edible seeds of pond-lilies were a vital source of carbohydrates.

Other institutions holding materials from Jones’s first summers in the west include Colorado State and Utah State Universities, and the New York and Missouri Botanical Gardens. At California Botanic Garden a digitization project designed to make Jones’s specimens more readily available to the public is largely complete. His writings were also extensive, numbering more than 250 articles, pamphlets, and book-length studies that provide a descriptive companion to the specimens he preserved. In addition to botanical discoveries, Jones published on climate, minerals, wildlife, and religion His major studies dealt with western ferns, willow trees, Locoweed (Astragalus), the plant he studied most extensively.

A man who could be blunt and disputatious, extremely self-confident and critical of others, Jones was viewed with distaste by some other botanists. But an appraisal of Marcus E. Jones begins with the acknowledgement that throughout his career of more than fifty years he was an outstanding field botanist. His biographer Lee Lenz reports that Jones saw more plants in their native habitats than any other plant scientist of his era. Lenz adds that Jones described more than 700 plants that were new to Euro-American botanists from his explorations of the western United States. An early promoter of the concept of ecology, Jones warned about the dangers of industrialization was causing to Nature. He is an important transitional figure between the traditional natural history approach of the nineteenth century, which featured widespread collecting and classifying, and the more scientific, laboratory-based “New Botany” of the twentieth.

Those two summer sojourns in Colorado helped transform Marcus Jones from a young man uncertain of his future into an individual committed to the study of botany and willing to make science the nucleus of his life. Colorado’s varied plant life and its invigorating climate, strikingly different from that of his native Iowa, drew Jones to the region. His explorations of Colorado’s mountains, which he likened to “immense tumbled stones built on the tomb of [flowers] dying at their feet” as well as its plains, canyons, and mesas, and the opportunities to write about them, convinced Jones that he was destined to become a Western botanist. Today, as the record of Western plant life he created gains additional significance as a benchmark to help scientists studying the effects of climate change understand how it is impacting the Rocky Mountain ecosystem, those two summers may prove consequential not just in shaping the rest of Jones’s life, but in shaping ours as well.