Story

“All the Camp was Weeping”

George Bent and the Sand Creek Massacre

Scholars have long relied on George Bent’s eyewitness accounts of the Sand Creek Massacre from his position within the Cheyenne and Arapaho encampment that day to better understand how such a horrific atrocity could have happened here in Colorado.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the Summer 1995 issue of Colorado Heritage. Some of the original images have been exchanged for photos and maps drawn from History Colorado’s exhibition, The Sand Creek Massacre: The Betrayal that Changed Cheyenne and Arapaho People Forever. Please note that, in places, the author uses language that was common at the time, but is no longer preferred nomenclature.

The high plains country of southeastern Colorado seems to roll on forever. Even today, above the Arkansas River near the course of the Big Sandy, sage and buffalo grass stretch as far as the eye can see. It is a rugged landscape: Treeless hills, sand, and cactus, and wind—always the wind.

It is dry here, ten inches or less rainfall in some years. Near the hamlet of Chivington—a remote crossroads some twenty-four miles north of Lamar—the Big Sandy does not flow at all. It is as dry as the surrounding hills. In winter and even spring, blizzards can strike with sudden and deadly force, as in 1931 when five children and their bus driver froze to death near the schoolhouse they had just left behind. In summer, temperatures soar into the hundreds. It is an unforgiving land.

And 132 years ago it turned violent. At dawn on November 29, 1864, along the Big Sandy—called “Sand Creek” by history—a thousand US volunteer troops under the command of Colonel John M. Chivington attacked a peaceful and unsuspecting village of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians.

In the sleeping village was George Bent. With him were his half-brother Charley; his sister, Julia; and his stepmother, Yellow Woman. Guiding the soldiers who had come to kill them all was Bent’s older brother, Robert.

Who was George Bent and why was he at Sand Creek on that day of death?

George Bent was born at Bent's Fort, July 7, 1843. His mother, Owl Woman, was from a prestigious Cheyenne family. Her father, White Thunder, was keeper of the Sacred Arrows and thus the spiritual leader of the Cheyennes. When Gerorge was born, his mother’s family was still regarded with deep reverence, even though White Thunder had been killed in battle five years before in a fight with the Kiowas.

Bent’s father was William Bent, the builder of Bent’s Fort and perhaps the most powerful white man in all the Upper Arkansas River county. His influence was enormous. With his trade empire based on the Arkansas River at Bent’s Fort, William Bent held sway over a territory stretching south into the Staked Plains of Texas and north into the Medicine Bow Mountains of the Upper Platte River. Most of the great names of the fur trade at one time or another were employed by him: Kit Carson, Jim Beckwourth, Old Bill Williams, Uncle Dick Wootton, and, on occasion, Thomas Fitzpatrick and Jim Bridger.

William’s brother, Charles, was a force in his own right; indeed, he had married into one of the richest and most influential of Taos families and, with signing of the treaty ending the Mexican War, soon was appointed the first territorial governor of New Mexico.

William had come to the Upper Arkansas River country in the 1820s, and with brothers Charles and George, along with Ceran St. Vrain, established Bent, St. Vrain & Company, a trading behemoth that brooked no rivals. To cement his influence among Cheyennes, William married Owl Woman in 1835, only a year after Bent’s Fort opened for trade.

Owl Woman and William watched over an ever-growing family. Mary was born in 1838, Robert in 1840, George in 1843, and Julia in 1846. When Owl Woman died giving birth to Julia, William followed Cheyenne custom and married her sister, Yellow Woman. Charley, George’s half-brother, was born sometime before 1850.

George Bent and his first wife Magpie pose for their wedding portrait around 1867. Magpie was the niece of famed peace chief Black Kettle, whose village was attacked at Sand Creek. Magpie here wears an expensive and elaborate elk’s tooth dress. George’s moccasins demonstrate the tug of two conflicting cultures he felt his entire life.

Raised at Bent’s Fort, George seldom lacked playmates. Indian women and their children of a dozen tribes lived at the fort and the Bent youngsters could always find something to do. “We could go out and play with the Indian children,” recalled George, “or go to the corral back of the fort and watch One-eyed Juan and his men riding and breaking the wild horses.” Even in the summer, when the men were away trading or hunting, there was excitement. Cheyenne and Arapaho war parties on their way to attack Ute and Pawnee camps often stopped over at the fort to dance through the night. The Bents looked on with rapt attention. In fall and winter, villages of Cheyennes and Arapahos were always just upriver from the fort, where George usually could be found with his stepmother nearby, learning the language and ways of the Cheyennes.

About this time he was given his Cheyenne name: Do-hah-en-no, or “Beaver.” In the spring of 1849 cholera struck the Cheyennes and other tribes of the Upper Arkansas. “Cramps,” the Indians called it, and they died by the hundreds. In one Cheyenne camp, George, saw a warrior mount his war horse and with lance in hand charge through the village shouting: “If I could see this thing, if I knew where it was, I would go there and kill it.” But as the warrior made his wild ride he was overcome by cramps and fell to the ground, dead. The people scattered in panic. Yellow Woman loaded George and Charley onto a travois and headed for Bent’s Fort. Surely they would find safety there.

Willian Bent, second from the left, poses in about 1867 with his Arapaho friends at Fort Hays, Kansas, while curious soldiers peer down from the roof in the background. Little Raven with his granddaughter are on the left, and Little Raven’s sons are at the right. William was the builder of Bent’s Old Fort and was perhaps the most influential man on the Great Plains, either Indian or white.

But not even behind the fort’s massive adobe walls was there safety. With death all around him and the business in shambles, William abandoned the castle of his dreams and moved to Big Timbers, an oasis of cottonwoods located thirty-five miles down river. Here, he built a temporary stockade and two trading houses on the high bluffs overlooking the Arkansas.

The Cheyennes followed their trusted friend and advisor. So, too, did the Arapahos, Kiowas, Comanches, and Plains Apaches—the dreaded cholera somehow left behind. The Cheyennes camped near the stockade, the others at a distance but still within hearing distance of the Bent children. George remembered the military society dances and the drums beating in the night, the sounds keeping him awake until dawn.

Then, in the spring of 1853, George Bent left the Cheyennes, not to see them again for another ten years. His father decided that it was time for the Bent children to leave the wilds of the Upper Arkansas for the streets of civilization. It was time for them to learn the ways of the whites. He wanted George and all of his children to know the sights and sounds of eastern life and its cities; to know good food, good clothes, and the value and power of money; to know quality fur and merchandise of all kinds; to know enough not to be bested in a trade transaction—whether by white or Indian.

Thus the Bent children were sent to Westport, Missouri. William entrusted their care to his friend and trade associate Colonel Albert G. Boone, the grandson of Daniel Boone and later Indian agent of the Upper Arkansas Agency. George remembered that Boone was not much liked by the Indians, nor for that matter by many whites, but he was a considerate, kindly guardian and the children enjoyed him and their stay in Westport. Here, George Bent attended public school, learning the three R’s.

After four years of public schooling in Westport, George was sent to Christian Brothers College in St. Louis. With George were Ceran St. Vrain’s son, Felix, as well as several Mexican children born on the Upper Arkansas River. After a year at Christain Brothers, George transferred to Webster College, another private—and expensive—institution.

Watching over the children in St. Louis was Robert Campbell, an old trader who had once furnished trade goods to one of the pioneers of the fur trade, William H. Ashley. George was happy these years and remembered Campbell with fondness. “He was a very old man then, but he was big man among all the Western men. He was fine old gentleman and stood away up in St. Louis [sic].”

Four years later, George Bent, now eighteen years old, was the proud possessor of a college education. He was, in fact, better educated than most Americans of the day; indeed, better educated than many of the Army officers and Indian agents he would come to know. Of course, because Cheyenne was his first language, he spoke English with a Cheyenne accent. Also, he thought first as a Cheyenne and his writings reflected as much.

Then came war.

In the spring of 1861 the long tension between North and South finally erupted in flame and smoke. George immediately felt the pull of the conflict. Out of school on summer vacation, he enlisted in the Confederate army as a private in the First Missouri Cavalry. Quickly trained in cavalry maneuvers and firearm use, he fought in the 1861 battles of Wilson Creek and Lexington, both in Missouri, then at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, in 1862.

After the siege of Corinth, in Mississippi, his luck ran out. On August 30, 1862 he was captured with 200 other Rebels near Memphis, Tennessee, and marched off to Gratiot Street Military Prison in St. Louis.

Then came a turn of good luck. St Louis had been his home for four years. He was known by his friends and by his schoolmates, and the Bent name was one of the city’s most prominent. As he and his fellow prisoners paraded through the streets on their way to Gratiot Street, George was recognized by an onlooker, a classmate it turned out. By another stroke of fortune, his oldest brother, Robert, was in the city transacting business for their father. The classmate ran to Robert, who in turn ran to Robert Campbell, George’s guardian. Campbell knew nearly every Union officer in St. Louis, and within the day General Charles C. Frémont, commander of the Union’s western army, drew up parole papers for the errant youth.

Such was the power of the Bent name.

On September 5, 1862, George signed an “Oath and Bond” pledging allegiance to the Union. That same day he was released to the custody of his father. He was going home.

But home was a far different place now. It was not the Bent’s Old Fort where he was raised. Nor was it the stockade he had left ten years before—that was government property and presently called Fort Lyon. “Home” was now his father’s new ranch on the Purgatoire River, a place he had never seen.

Too, when George left for Westport, hardly a white was to be found on the Upper Arkansas. Rather, the lands belonged to his people, the Cheyennes. Now, whites were everywhere in the territory called Colorado. Gold seekers by the thousands pounded the roads leading to the mountains and the much sought-after yellow metal. At the confluence of Cherry Creek and the South Platte River, Denver was a sprawling town filled with a humanity drawn from around the world. Along the Arkansas River, ranches and stage stations crowded out Cheyenne and Arapaho villages.

Of course, change came to the Cheyennes as well. Before George left for Westport, the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty gave to the Cheyennes and Arapahos—forever, it was said—all of the land lying between the Platte and Arkansas rivers, and between the Rocky Mountains and the Smoky Hill country.

Forever was less than ten years.

The sweep of new immigration demanded a new treaty—the 1861 Treaty of Fort Wise. Now the Cheyennes and Arapahos were restricted to a small triangular-shaped reservation in east-central Colorado. Bounded on the south by the Arkansas River and on the east by Sand Creek, it was a desolate piece of land, chosen primarily for its remoteness. Its only redeeming feature was that it still supported buffalo, although most Cheyennes knew that these few herds would disappear. There were simply too many foreigners on the land.

In any case, no one understood the terms of the treaty. Agent A.G. Boone had asked some of the chiefs to sign—Black Kettle and White Antelope of the Southern Cheyennes, for example—and they did. But many more did not. Certainly the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers did not sign; they would never consent to any treaty which confined their movements to the empty plains of eastern Colorado. Finally, there was Fort Lyon. It stood near where George had said goodbye to his childhood only ten years before. Now it was a Union post. Enemies lurked there.

Nevertheless, during the first months of his return, George was a regular visitor to Fort Lyon, for his father frequently had business there. The soldiers were respectful of William. But his son was a paroled Confederate prisoner of war. Worse, he was an unreconstructed Rebel. Even the Cheyennes called him “Tejanoi”—literally “Texan,” for in their experience all Texans were Confederates.

Inevitably, there were harsh words between the soldiers and this Rebel among them. The soldiers complained that George threw the words “Damn Yankee” at them. This was unacceptable. An officer warned George that if he continued such behavior he would be placed in irons.

There was nothing else to do. In April 1863 George left his father’s ranch and moved in with his mother’s people, Black Kettle’s band of Southern Cheyennes.

George now entered fully into the life of a Cheyenne warrior. All warriors belonged to one of six military societies: Crooked Lances or Bone Scrapers, Crazy Dogs, Dog Soldiers, Red Shields, Kit Foxes, Bowstring Men, and Chief’s band. Each society had its own tradition and ceremonies, its own feasts and dances. George chose the Crooked Lances or Bone Scrapers: “Our men all had lances with one end curved like a shepherd’s crook.”

As a Crooked Lance, George joined other young men on raids against the Utes, Pawness, and other enemies of the people. In the summer of 1863, on Solomon’s Fork in central Kansas, he ran into a band of Delaware trappers and participated in his first fight as a Cheyenne. Displaced from their eastern homelands, the Delawares were renowned trappers and scouts. According to George, the Cheyennes “did not want to fight them. The Delawares commenced this fight.” At any rate it was a sharp affair. The Cheyennes killed two of the enemy and captured all their horses and beaver pelts. But not without loss. In the encounter, George’s friend, Big Head, was killed.

Charley, George’s half brother, also joined the Cheyennes, a fact not unnoticed in the white settlements. Armed encounters between Cheyennes and whites had now increased in frequency, and wild rumors circulated in Denver and the mountain camps crediting the Bent boys for leading war parties against ranches and stage stations on the South Platte. “People at Denver thought I was with the Indians in all their raids on South Platte in 1864. I was very cautious about visiting any posts. I also kept away from my father’s ranch at the mouth of Purgatoire twenty-five miles above Fort Lyon."

In truth, for most whites George Bent was an intimidating figure. He was a trained Confederate soldier and a veteran of several major battles. He knew the use of all manner of weaponry—musket, rifle, pistol, artillery, lance, bow and arrow. He was familiar with army tactics. He was an expert horseman. He was fluent in English and presumably able to intercept dispatches, thereby disrupting the army’s plans. And he was an experienced Cheyenne warrior. This, together with the fact that he stood nearly six feet tall and weighed two hundred pounds, makes it understandable why he was the subject of rumors and speculation. Mounted on a horse, stripped down to a breechcloth, and armed with a rifle or lance, he must have been positively menacing.

But he was not an enemy of the whites. Nor were Black Kettle and the Southern Cheyenne. To be sure, fights between Cheyennes and whites occurred, but these clashes usually involved either Lakota warriors or a separate division of the Cheyennes known as the Dog Soldiers.

The Dog Soldiers emerged as a separate entity of the Cheyennes sometime in the 1830s. George Bent called them a “renegade” band, meaning simply that at one time their leader, Porcupine Bear, had been exiled from the main body of the people. Through the years, however, their numbers and influence grew, until by the 1860s they were a powerful—and militant—force. Led by Bull Bear and Tall Bull, the Dog Soldiers were determined to resist white encroachment.

By August 1864, regardless of the efforts of peace makers on both sides, war was at hand. Back in April, US troops had clashed with Dog Soldiers at Fremont’s Orchard on the South Platte. In May, the Southern Cheyenne peace chief, Lean Bear, was shot down by troops while displaying a flag of truce. In June, Nathan Ward Hungate, his wife, and two children were murdered on Box Elder Creek, thirty miles southeast of Denver. When the mutilated bodies were recovered and placed on public display, panic seized Denver. The Cheyennes were blamed.

A poster advertised for “hundred-day volunteers” to “solve” the Indian war of 1864. These hundred-day volunteers were authorized by the federal government and was present at the Sand Creek Massacre.

Late in June, Colorado Territorial Governor John Evans called on all “Friendly Indians of the Plains” to go to places of “safety”—military forts—and there surrender to the authorities. Those who did not come in would be considered hostile. Evans sent out William Bent to spread the word among the Cheyennes near Fort Lyon, an authorized place of “safety.”

In August, Evans issued a contradictory proclamation, this one authorizing the “citizens” of Colorado to “kill and destroy” all hostile Indians on sight. As to which Indians were hostile and which were friendly, the proclamation did not explain.

In any event, a few days later both proclamations were rendered null and void. Evans received word that the War Department had approved his request to raise a regiment of 100-day volunteers—the Colorado Third—to “pursue, kill, and destroy all hostile Indians that infest the plains.”

In the Cheyenne camps, Black Kettle and other leaders watched these developments with alarm. Hundred-day volunteers would shoot first and ask questions later.

On the Solomon River, Black Kettle’s Cheyennes and Spotted Tail’s band of Lakotas deliberated on ways to avoid war with the soldiers. The result was a letter written in George Bent's hand addressed to Major Samuel G. Colley, Indian agent of the Upper Arkansas Agency and signed by “Black Kettle and other Chieves."

Cheyenne Village, August. 29th/64

Maj. Colley

Sir:

We have received a letter from [William] Bent wishing us to make peace. We held a consel in regard to it & all came to the conclusion to make peace with you providing you make peace with the Kiowas, Commenches, Arrapahoes, Apaches and Siouxs. We are going to send a messenger to the Kiowas and to the other nations about our going to make peace with you. We heard that you have some prisoners in Denver. We have seven prisoners of you which we are willing to give up providing you give up yours. There are three war parties out yet and two of Arrapahoes. They have been out some time and expect now soon.

When we held counsel there were few Arrapahoes and Siouxs present. We want true news from you in return, that is a letter.

From this hurried and grammatically flawed scribbling came a remarkable meeting between Major Edward W. Wynkoop, commander of Fort Lyon and the officer who first received George’s letter, and the combined forces of the Dog Soldiers and Black Kettle’s Southern Cheyennes. With John S. Smith and George Bent acting as official interpreters, the council took place on Hackberry Creek south of Fort Wallace in western Kansas. As promised, the Cheyennes surrendered their prisoners and agreed to accompany Wynkoop to Camp Weld in Denver to meet with Governor Evans and Colonel John M. Chivington, the commander of the Colorado Military district.

On September 28, 1864, at Camp Weld, the Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs for the first time confronted Evans and Chivington. Many things were said that day, but the Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs held on to Chivington’s final words:

“I am not a big war chief, but all the soldiers in this country are at my command. My rule of fighting white men or Indians, is to fight them until they lay down their arms and submit to military authority. You [the Cheyennes and Arapahos] are nearer Major Wynkoop than anyone else, and they can go to him when they get ready to do that."

This famous photograph, taken at the Camp Weld conference in Denver in September 1864, has frequently misidentified the participants shown. According to George Bent, who knew the principals and was also at Sand Creek, the correct known identifications are as follows. Kneeling front, from left: Major Edward W. Wynkoop and Captain Silas Soule. Seated, first row, from left: Neva (Arapaho), Bull Bear (Cheyenne), Black Kettle (Cheyenne), White Antelope (Cheyenne), and Na-ta-nee (Arapaho). Back row: unidentified; unidentified but possible Dexter Colley, son of Indian agent Samuel Colley; U.S interpreter John Smith, whose son Jack was murdered at Sand Creek; Heap of Buffalo (Cheyenne); Bosse (Arapaho); unidentified but possibly Samuel Elbert, secretary of Colorado Territory; unidentified.

George Bent was not present at the Camp Weld Conference—“I was away with war-party hunting Pawnees when [Wynkoop] took the chiefs to Denver.” When he returned, he risked a visit to his father’s ranch on the Purgatoire River: “I was at my father’s ranch for good while and never heard of Chivington coming to attack the Cheyenne village.”

No one else did either. By late September, the ranks of the federally authorized Third Regiment of Colorado Volunteers were filled—ten companies of about a thousand troops in all. But Colonel Chivington was busy with civilian matters. Coloradans were voting yea or nay on the question of statehood, and Chivington was on the ballot as a nominee for Congress. There was no time for military matters, and in any case, the Cheyennes under Black Kettle and the Arapahos under Little Raven and Left Hand had obeyed Chivington’s injunction to go to Fort Lyon and surrender to military authority there. Despite the calling out of the 100-day volunteers and all the attendant uproar over hostile Indians besieging Denver, it seemed war on the plains was over. Indeed, newspapers in Denver had taken to calling the new regiment the “Bloodless Third.”

In November, Evans boarded a stage and headed off to Washington, DC, presumably for other and more pressing business.

At Fort Lyon, Major Wynkoop received the Arapahos, who had come calling. “I told the chiefs to bring in their villages to the post, where they would be under my own eye.” They would be safe here, Wynkoop said, “and under my protection from the government, given to them myself, as a United States officer. I at different times issued a limited amount of rations to them.” Wynkoop believed he had no choice but to issue such subsistence.

With buffalo long since gone from the area, the Arapahos were starving.

Meanwhile, Black Kettle and White Antelope had led 500 Southern Cheyennes to the great bend of Sand Creek, forty miles above Fort Lyon.

So matters rested until November 2, 1864, when Major Scott J. Anthony, First Colorado Cavalry, arrived at Fort Lyon and relieved Wynkoop of command. Anthony was under strict orders not to make peace with the Indians—not until they had been properly punished. But the Indians at Fort Lyon were there at Chivington’s orders, Wynkoop had placed them under the protection of the flag of the United States, and they were starving. So, although his order forbade it, Anthony continued Wynkoop’s policy of rationing, even increasing the amount issued. As a precaution, however, he ordered the Arapahos to deliver up their arms. They did so, according to a witness, “without hesitation.” Later, in mid-November, Black Kettle rode in to see the new soldier chief. Present at the council, besides Anthony, Wynkoop, and the Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs, were Captain Silas S. Soule, Lieutenant Joseph A. Cramer, Lieutenant William P. Minton, Lieutenant Charles E. Phillips, and the agent of the Cheyennes and Arapahos. Samuel G. Colley. Robert Bent, George’s older brother and an employee at Fort Lyon, acted as interpreter.

Wynkoop told the assembled chiefs that he was no longer in command but assured them that Major Anthony would continue the policy he had laid down. Anthony then stood up and advised Black Kettle to keep his people at Sand Creek. “No war will be waged against you,” he promised. In fact, nothing would be done with the Cheyennes until he received instructions from his superiors. Then Anthony said he would send a runner out to the camp and let them know their “final disposition.” Until then, they should remain at Sand Creek, where they would be under government protection.

With regard to the Arapaho, Anthony advised them to join the Cheyennes at Sand Creek. Little Raven, suspicious, moved his people down the Arkansas River some seventy-five miles. But Left Hand, ill and tired, agreed and took his small band of eight lodges out to Sand Creek. Perhaps there were buffalo there, away from the fort.

On November 26, Anthony asked Old John Smith, the government interpreter, to go out to Sand Creek and report on the situation there. Smith jumped at the chance. His wife and son were out there, and he wanted to do some trading. He asked permission to take along one of the teamsters, “Watt” Clark, to help haul the goods, and to provide protection on the way, Private David H. Louderback. Louderback was eager to go; he had never been in an Indian camp before. Anthony saw no reason to deny the request, and the three men departed for Sand Creek that afternoon.

Wynkoop also left that day to report to his superiors and explain his actions. He left armed with two letters endorsing his policy toward the Indians ever since his return from Camp Weld Conference. One was signed by seven officers at Fort Lyon, commending him for keeping the peace with the Indians and thereby “saving the lives of hundreds of men, women, and children.” The other letter, signed by twenty-six Arkansas Valley ranchers—including George Bent’s former guardian, Albert G. Boone—expressed the belief that Wynkoop’s policy towards the Indians was “right, politic, and just.”

The same day, too—November 26, 1864—George Bent with half-Brother Charley and sister Julia, rode into Chief Black Kettle's camp. Because Anthony had adopted Wynkoop’s policy of peace, William Bent thought it safe for his family to return to the Cheyennes. Surely there would be no war now, not with the Camp Weld Conference and Chivington’s instruction for all “friendly Indians” to place themselves under military protection.

And then Colonel Chivington stirred. For weeks, the newspapers had been restive. When news reporters questioned him about his plans. Chivington spoke vaguely of “chastising and punishing” the Indians. But nothing specific. No one—not his commanders, not Governor Evans, not his military superiors, and not even his friend, editor William N. Byers of the Rocky Mountain News—knew what Chivington was planning.

Colonel John M. Chivington, sometimes presiding elder of Denver’s Methodist Episcopal Church and commander of the Colorado Military District. Chivington led the attack on Sand Creek, and ever after his name has been shrouded in controversy.

On November 24, Chivington appeared at Booneville near Pueblo on the Arkansas River, and assumed command of the Colorado Third Regiment. The next day he rode through Booneville, heading downriver for Fort Lyon. All the while, Chivington kept the Third’s movement a closely held secret. Mail carriers on the road were detained, ranchers were surrounded and cordoned off, and stages were stopped.

On November 25, the troops reached the Prowers and Bent ranches. John Powers was married to Amache, the daughter of Cheyenne chief One-Eye, and thus was the enemy. Chivington placed Powers under arrest and disarmed his seven ranch hands. At Bent’s Ranch on the Purgatorie, Chivington found William at home with his son Robert. Here, too, a guard was placed and William was confined to quarters.

Robert Bent, however, was pressed into government service. Chivington’s guide Old Jim Beckwourth, one of the greats of the fur trade, was feeling the cold and needed help. And Robert knew where Sand Creek was. “Colonel Chivington ordered me to accompany him on his way to Sand Creek,” Robert testified later. “The command consisted of nine hundred to one thousand men.” Having no choices, Robert mounted his horse and joined the soldiers. Sand Creek and Black Kettle. It was Chivington’s destination all along. Not the soldiers or the “hostile” camps out on the Smoky Hill. But Black Kettle's peaceful—and protected—village at Sand Creek.

Chivington arrived at Fort Lyon on November 28. He was in a hurry. Was it true that Black Kettle was camped on Sand Creek? The officers assured him that it was. But they also explained to him that Black Kettle and the Southern Cheyennes were under protection of the United States flag. Attacking them would be wrong; killing them would be murder.

Chivington lifted his six-foot, four-inch frame out of his chair and shouted: “Damn any man who is in sympathy with an Indian!”

This seemed to convince Major Anthony, who said he had always wanted to attack Black Kettle but had waited until he had sufficient force. Now with “sufficient force” he attached 125 of his own men and two 12-pound howitzers to Chivington’s command and joined the Sand Creek expedition.

“We left Fort Lyon at eight o'clock in the evening,” said Robert Bent. “We came on to the Indian camp at daylight. When we came sight of the camp I saw the American flag waving and heard Black Kettle tell the Indians to stand round the flag. I think it was a garrison flag, six by twelve.”

George Bent was sleeping when he heard the cry “Soldiers coming!”

Grabbing his rifle and ammunition and little else, Bent dashed outside and observed mounted soldiers charging the village, one company veering to the east, the other to the west. He quickly looked over to Black Kettle’s lodge and, as he recalled later, saw a large American flag, “on a lodge pole in front of his lodge.” Black Kettle was shouting for the people to have heart, not to run “as he had been told by whites, the troops would not attack his village.” Women and children huddled near him, crying out in fear. What should they do? White Antelope, who was nearby, ran towards the soldiers. Then heavy firing broke from all sides of the village. As White Antelope advanced towards the soldiers, he raised his arms over his head to show his empty hands. George heard him singing a familiar Cheyenne death song: “Only the mountains live forever.” And then White Antelope fell, cut down in a storm of soldiers’ gunfire.

Bullets, said George Bent later, now flew “thick at all of us—men, women and children.” Black Kettle’s wife was knocked down, hit nine times. Both George and Black Kettle supposed her dead, so they left her. There was nothing else to do; the soldiers were upon them. With Little Bear, Spotted Horse, Big Bear, and Bear Shield, George and Black Kettle started for the sand pits on the west side of the camp where they hoped to make a stand. But they observed too many soldiers, so they headed for the upper end of the village. Here they learned that the old people had dug holes in the soft sand about two miles up Sand Creek. George Bent remembered that it was like running “through fire,” the soldiers on all sides, shooting. A bullet slammed into George’s hip, but he kept on running. As he and the other warriors continued on, they saw the dead everywhere, women and children and the old people. Then they reached the sand pits, which, Bent recalled, were “dug against the banks. This is what saved good many men, women and children.”

When the soldiers attacked that morning, Charley Bent was sharing a lodge with another mixed blood, Ed Guerrier, and three Fort Lyon men—John Smith, David Louderback, and Watt Clark. It was Louderback’s first time in an Indian camp. To him the approaching din sounded like buffalo, but the others told him it sounded more like approaching soldiers. Surely they would not fire on their own people. Again he was mistaken. One soldier, recognizing John Smith, yelled out:”Kill the son of bitch. He’s no better than an Indian!”

Teamster Clark found a white handkerchief, tied it on a stick, and waved it at the soldiers. Despite the clouds of smoke and the screams of the women and children, Smith somehow spotted Chivington and shouted to him that his (Smith’s) lodge was filled with whites. Chivington told Smith to bring his friends over, and they would be safe. Smith obeyed, bringing Louderback and Charley with him. Guerrier went his own way: “When I saw I could not get to them, I struck out; I left the soldier and Smith and went northeast. I ran about five miles,” he testified later. Guerrier by chance came across his cousins, one of White Antelope’s daughters, who had horses with her. The two of them made their way to the Smoky Hill camp and safety.

Charley Bent was by no means clear of danger, When he came across to the soldiers, he was placed under arrest. But Chivington’s orders were unmistakable: No Prisoners. Old mountain man Jim Beckwourth was present when Charley was arrested. Charley, he said, “begged of me to save his life. I put him in an ambulance with Captain Talburt and got him safe into camp.”

Chivington asked Robert Bent what should be done about his half-brother Charley. Robert was cautious. A wrong word, a wrong gesture could get his brother shot. Quietly, he told Chivington that he “didn’t much care,” but guessed it would be all right to turn him over to Captain Soule. That afternoon, at two o'clock, Soule took Charley and three Cheyenne women to Fort Lyon. From there, Charley was released to his father.

Again, the power of the Bent name.

As comparison, Jack Smith, the mixed-blood son of US interpreter John Smith, was also taken prisoner. Unlike Charley, Jack was not released. He was shot the morning after his arrest. The soldiers then dragged him behind a horse through the burning village until not even his father could recognize the body.

While Charley was being rescued, George was above the village fighting from the sand pits. When the troops made a close-in charge, George, with two other warriors, Spotted Horse and Bear Shield, leaped from the pit and took cover in another hole closer to the sand bank. This saved their lives. Those who remained behind were all killed.

Finally, late in the afternoon, the soldiers withdrew. As night fell, the temperature plummeted and the wounded suffered terribly. George Bent said later: “About half of us were wounded. I myself was badly wounded in the hip. As there were no bones broke I was able to walk.”

Black Kettle, however, used the darkness to steal into the village to recover his wife’s body. To his amazement and joy, she was alive. He gently lifted her up and carried her on his back until others came up with horses. Together they made their way to the Smoky Hill.

George had no horses to ride. He managed to walk ten miles to a ravine, where he fell exhausted. He recalled: “It was very dark and cold, and those that were not wounded kept up the grass fires as there was not wood or blankets to keep the wounded from freezing. Of course, no one slept. Wounds began to pain.” Other warriors, those not wounded, made their way to the village on the Smoky Hill, fifty miles distant. At dawn they miraculously returned with horses. “My hip was very swollen and sore from cold,” said Bent. “After daylight we began to meet Indians from the village on the Smoky who brought ponies with saddles and buffalo robes and meat.”

When the survivors reached the Smoky Hill village far from the horrors of Sand Creek, there were no celebrations. “All the camp was weeping for the dead,” said George. The villages of the Cheyennes would be weeping for years to come.

Epilogue

George Bent wrote that after Sand Creek, in war and peace, he remained with the Cheyennes. He was good to his word. When he recovered from his hip wound, he joined the Cheyennes in revenge raids against US troops. He rode with the Dog Soldiers in the sacks of Julesburg, Colorado, in January and February 1865, and helped with the Cheyennes at the Battle of Platte River Bridge in July 1865, where Lieutenant Caspar [sic] Collins, the name-sake of Casper, Wyoming, was killed. Later that summer, he was with Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Lakota warriors in Montana against General Patrick E. Conner’s grand Army of the Plains. In 1866, he became an official US interpreter, a position he held throughout his life, and translated for his people at the 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty negotiations. When the Cheyennes were removed to the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation in Oklahoma, he joined them, thus leaving behind the white world and the riches of his father’s estate. He died penniless in 1918 in Colony, Oklahoma, on former reservation lands.

This map shows the vast amount of land the Cheyenne and Arapaho were coerced into giving up between the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty and the 1861 Treaty of Fort Wise.

Julia Bent and her stepmother, Yellow Woman, survived Sand Creek. Julia married Ed Guerrier, after whom Geary, Oklahoma, was named. Yellow Woman was killed by Pawnee government scouts in Montana in 1865, during General Connor’s Powder River Campaign against Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Lakota warriors.

Charley Bent, who joined his brother George in raids against US troops, died in 1867 from wounds suffered in a fight with the Pawnees. Robert Bent survived Sand Creek and continued work as a US interpreter. With his brother George, he moved to the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation in Oklahoma. He died in 1889.

William Bent lived to see his children receive title to land on the Arkansas River as payment for their suffering at Sand Creek. He died in Colorado at his Purgatoire River ranch in 1869. His estate was valued at $200,000.

Black Kettle and his wife were killed in 1868 on Washita River, Indian Territory, by troops of the Seventh Cavalry under command of Lieutenant Colonel Geoerge A. Custer.

John M. Chivington and the Third Colorado returned to Denver to a heroes’ welcome. Sand Creek “trophies,” including Cheyenne scalps and other body parts, were displayed at a Denver theater. Chivington’s actions at Sand Creek were investigated by three government bodies. Chivington, however, resigned from the Army, and no charges were ever brought against him. After returning to Denver in 1883, Chivington served as city coroner. He died in Denver in 1894.

Major Edward W. Wynkoop was appointed agent for the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes in 1865, a position he resigned in protest three years later when the US government again targeted those two tribes for military action. He died in New Mexico in 1891, a forgotten man except to a few.

Captain Silas Soule testified against Chivington during the War Department’s hearings into Sand Creek. Shortly after his testimony, he was shot and killed in the streets of Denver by a Chivington supporter.

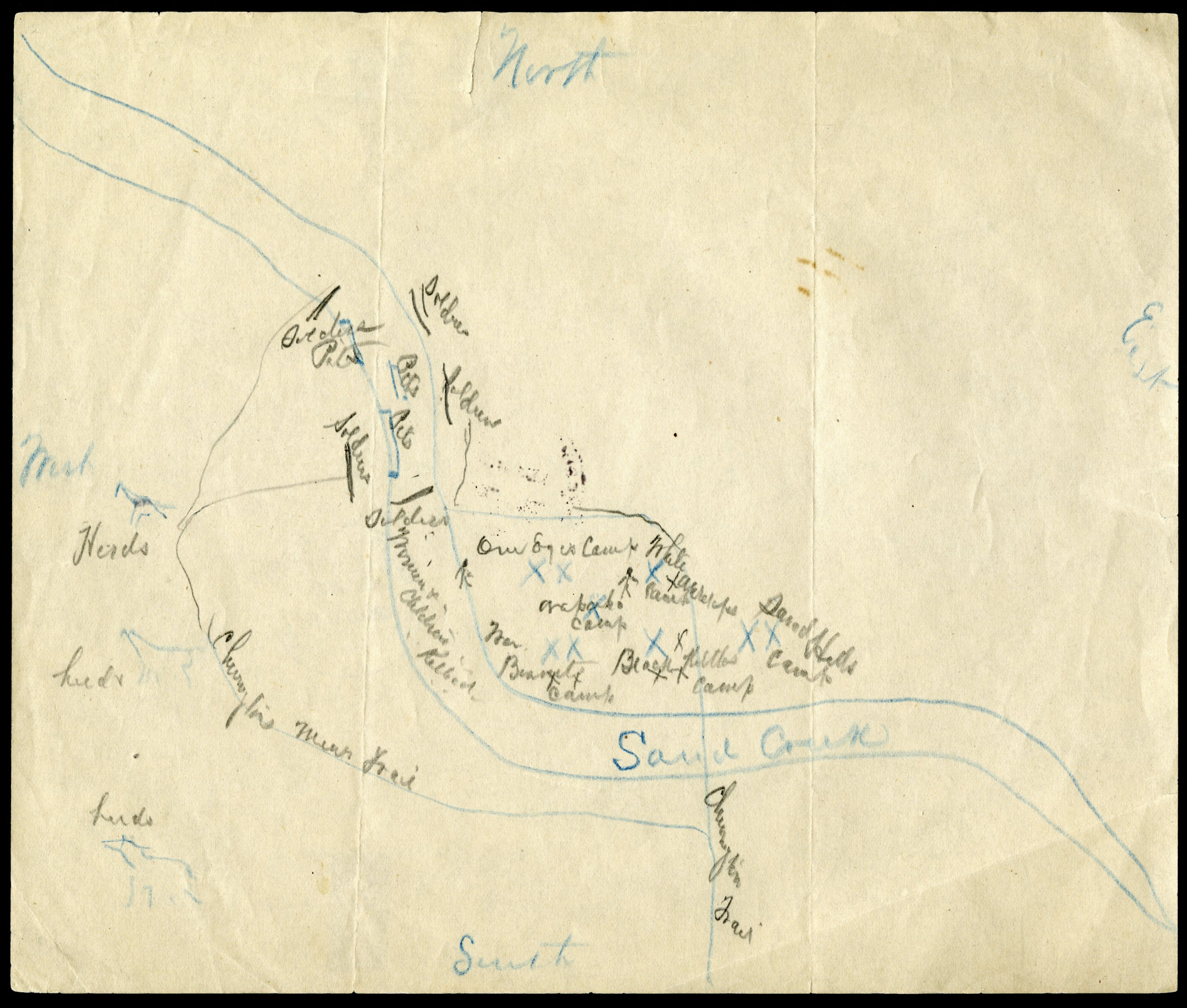

George Bent's hand-drawn map of the Sand Creek Massacre. Bent's lifelong work to make sure Sand Creek was never forgotten was essential to establishing the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site in 2007.

Governor John Evans was held responsible for Sand Creek and was removed from office by President Andrew Johnson. He died in Denver in 1897 after a distinguished career as a physician, business leader, and philanthropist.

By the 1865 Treaty of the Little Arkansas, the US government admitted guilt for the Sand Creek Massacre. In article Six, it promised to pay reparation to 112 Cheyenne heads of families who suffered loss of either property or life as result of the unprovoked attack. Although the treaty was ratified by the Senate and proclaimed by the President, the promised reparations were never paid.

The author wishes to thank Chief Laird Cometsevah, president of the Southern Cheyenne Sand Creek Descendants Association, and the following Cheyennes for their assistance in the preparation of this article: Collen Cometsevah, a Sand Creek descendant and Cheyenne genealogist; Joe Big Medicine, Sun Dance Priest; and Terry Wilson, Arrow Priest.

For Further Reading

Any study of George Bent must begin with the Life of George Bent Written from His Letters, by George Hyde and edited by Savoie Lottinville (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968). Compiled by Hyde many years before, the manuscript languished unpublished for fifty years in the Denver Public Library. In the early 1900s Hyde and Bent tried mightily to find a publisher, but were unsuccessful. Hyde even asked George Bird Grinnell to take the project on, hoping the well-known ethnologist and friend of President Theodore Roosevelt would use his political connections to gather financial backing. The published version, however, must be used with caution. Hyde rewrote Bent’s letters, and although he tried to preserve the flavor and sense of the original, it was still Hyde we read, not Bent. Entirely lost to the reader are Bent’s unique expressions and his revealing grammatical quirks. Also vital to an understanding of Bent and his life in the Upper Arkansas River country is Bent’s Fort, by David Lavender (Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1954.). Lavender’s book is both sensitive and accurate. Essential,too, are Donald J. Berthrong’s masterful works on the Cheyennes: The Cheyenne and Arapaho Ordeal: Reservation and Agency Life in the Indian Territory, 1875-1907 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976); and The Southern Cheyennes (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1963). Although not a biography of Bent, George Bird Grinnell’s groundbreaking The Fighting Cheyennes (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1915) is largely based in information provided by Bent. However, Grinnell—predictably—disguises this fact by burying Bent’s name in a long list of contributors.

All of these works aside, the only manner in which to truly reach Bent is through his original letters. The largest collection is the Bent-Hyde correspondence in the Beinecke Library at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. Now available on microfilm, these letters not only reveal much about Bent, but also are essential for an understanding of nineteenth-century Cheyenne life. Other significant collections of Bent correspondence are housed at the Colorado Historical Society, Denver; the Western History Department, Denver Public Library; the University of Colorado Library, Boulder; the Indian Archives at the Oklahoma Historical Society, Oklahoma City; and the George Bird Grinnell Papers at the Southwest Museum, Los Angeles.

The standard published work on Sand Creek and its surrounding controversy is Stan Hoig’s The Sand Creek Massacre (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961). However, Gary Robert’s unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, “Sand Creek: Tragedy and Symbol,” (University of Oklahoma, 1984) is the most readable, detailed, and accurate scholarly study yet done regarding the massacre. A readable account written for a general audience is Song of Sorrow: Massacre at Sand Creek, by Patrick M. Mendoza (Denver: Willow Wind Publishing Company, 1993). Michael Straight’s A Very Small Remnant (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1963) is an interesting, challenging, fictional look at Sand Creek.

But the best way to follow the twist and bends of Sand Creek and its surrounding controversy is to consult the pertinent contemporary government documents. See Senate Executive Document No. 26, 39th Cong., 2nd Sess., Report of the Secretary of War, Communicating … a Copy of the Evidence Taken at Denver and Fort Lyon, Colorado Territory by a Military Commission Ordered to Inquire into the Sand Creek Massacre, November, 1864 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1867); Senate Executive Document No. 13, 40th Congress, 1st Session, Report to the Senate on the Origin and Progress of Indian Hostilities on the Frontier (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1867); and Senate Report No. 142, 38th Congress, 2nd Session, Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, 3 vols (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1865). Fortunately, these have been reprinted in one convenient volume under the title The Sand Creek Massacre: A Documentary History, edited by John M. Carroll (New York: Sol Lewis, 1973).