Story

Saving the Soule-Cramer Letters

How a government copyist “saved” two lost accounts of the Sand Creek Massacre

Editor’s note: This article was published in the November / December issue of Colorado Heritage in 2014. It is reprinted here as it first appeared. Copies and audio recordings of the Soule-Cramer letters are featured in History Colorado’s exhibition, The Sand Creek Massacre: The Betrayal that Changed Cheyenne and Arapaho People Forever.

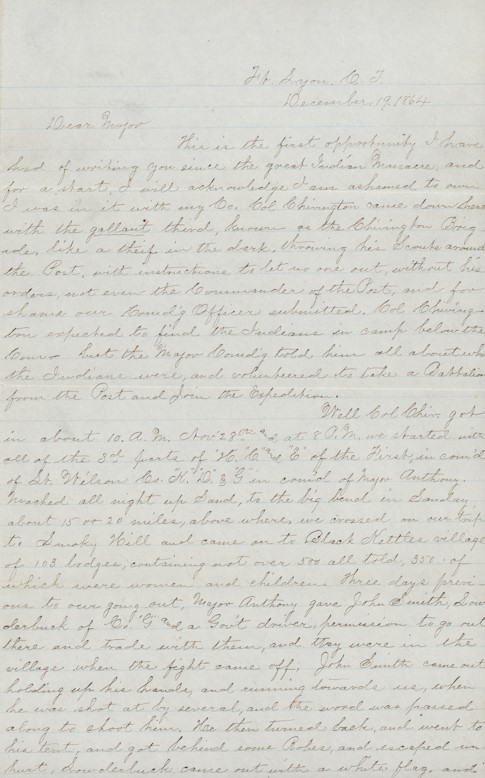

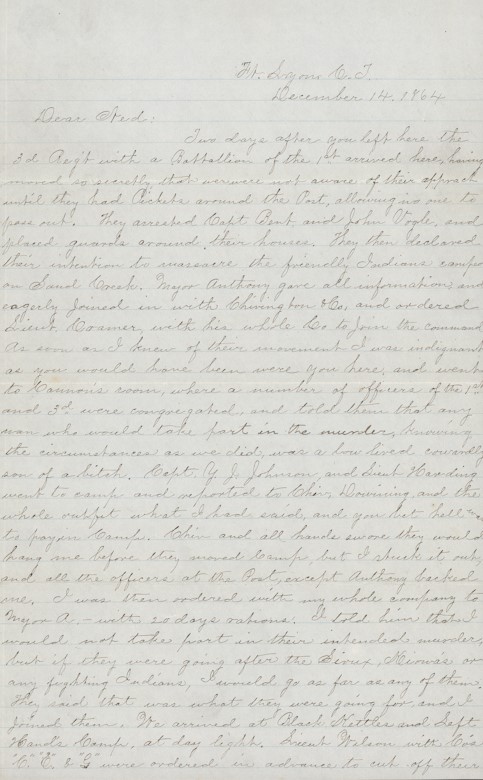

On December 14, 1864, two weeks after the Sand Creek Massacre, Captain Silas Soule wrote to his friend Ned Wynkoop: “Dear Ned, two days after you left here the 3rd Reg’t arrived….They declared their intention to massacre the friendly Indians camped at Sand Creek….I told them I would not take part in their intended murder.”

The copy of the letter to Major Edward Wynkoop from Captain Silas S. Soule. The captain was later assassinated in Denver for his testimony as to the horrors of the unjustified attack at Sand Creek.

Soule went on to describe in graphic detail the horror of that day. “The massacre lasted six to eight hours. I tell you Ned it was hard to see little children…it was almost impossible to save any of them.” As he drew his correspondence to a close, he remarked, “I suppose Cramer has written to you all the particulars…” Five days later, Lt. Joseph Cramer communicated with Wynkoop, sharing his own experience. Soule’s and Cramer's detailed accounts prompted the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War and the US Army to launch investigations of the massacre in early 1865. Their reports, published in 1865 (Congress) and 1867 (US Army), prevented the details of the massacre from being swept under the rug.

Soule’s and Cramer’s letters changed history. Copies of them circulated among officials and supporters. Then, they disappeared.

In 2000, on the eve of an important Congressional hearing regarding the authorization of the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, the Colorado Historical Society’s then-chief historian, David Fridtjof Halaas, made a startling discovery. Among the family papers of a metro-Denver resident were copies of the two “lost” letters, penned by Captain Silas Soule and Lieutenant Joseph Cramer in order to alert authorities to the nature of the massacre. In 1864, the letters had helped spark government investigations that uncovered the truth. Appearing just prior to the Congressional hearing in 2000, the letters stimulated support for the creation of the historic site.

The discovery of the Soule-Cramer letters, and their recognition as critical evidence regarding the nature of the Sand Creek Massacre, made newspaper headlines in 2000. Less celebrated was the fact that the letters were copies of the originals, and that they comprised part of a packet of documents that included correspondence, circulars, and copies of eyewitness affidavits generated during the course of official investigations into the massacre. With the 150th anniversary of the Sand Creek Massacre approaching, History Colorado curators sought out the documents’ owner in order to re-examine and preserve the Soule-Cramer letters, along with their companion papers. Taken together, these papers provide a valuable glimpse into the government investigative process that uncovered and publicized the details of the massacre.

The story picks up in June 2000, when Colorado resident Linda Rebeck contacted the Colorado Historical Society (today’s History Colorado) about a packet of affidavits and letters related to Sand Creek found in a trunk of family possessions. Linda’s great-grandfather, Mark Blunt, was a rancher who had provided supplies to Fort Lyon before and after Sand Creek. The trunk went to his daughter–Linda’s great-aunt–and then to Linda’s mother, who found the documents and brought them to Linda’s attention.

In addition to copies of the letters from Soule and Cramer, the packet contained a circular, three letters, and six affidavits. One letter and the circular are attributed to Governor John Evans. The letter, dated June 16, 1864, was a communication to Major S.G. Colby at Fort Lyon, instructing him to make preparations for the feeding and support of friendly Cheyenne and Arapaho people in the vicinity of the fort, where they were to maintain a camp separated from those expressing hostility. The proclamation, bearing a date of June 27, 1864, was addressed to “the friendly Indians of the plains” instructing Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, and Comanche to report to Fort Lyon, Fort Laramie, Fort Larned, or Camp Collins. The object was “to prevent friendly Indians from being killed by mistake.”

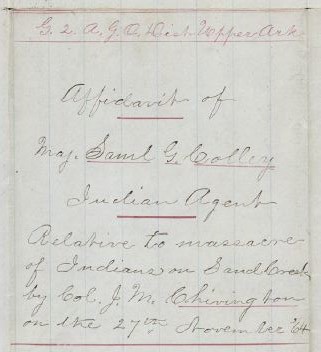

The six affidavits, each ranging from one to nine pages in length, provided sworn testimony from the civilian trader and interpreter John Simpson Smith, Lt. James D. Cannon (alternately spelled Cannan), Pvt. David Lauderback, Lt. W.P. Minton, Maj. Samuel Colley (the Indian Agent for the Cheyennes and Arapahos), and Capt. R.A. Hill. The affidavits, by their structure, characteristics, and notations, show the process employed by military investigations. A team of officers worked together to hear and record information. An officer designated as Post Adjutant was responsible for managing administrative and bureaucratic functions of a military post, including collecting, recording, and transmitting information for reports, correspondence, and communications. Most of the documents found in the packet bear the signature of one of two Adjutant officers: 2nd Lt. W.P. Minton 1st Infantry, New Mexico Volunteers, or 2nd Lt. W.W. Dennison, 1st Colorado Veteran Battalion. In their respective roles, they heard the sworn testimony of the soldiers and certified that the collected information was true and accurate. Adjutant officers and their staff assembled and maintained the documents produced and were responsible for making copies for distribution. Each of these affidavits, as well as the other documents, subsequently made their way into the official reports on the massacre.

Adjutants and their staff served as part of the regular communication network between forts and managed correspondence, as evidenced in Governor John Evans’s letter and circular. Neither appears in his handwriting but rather that of Lt. Dennison. No printing presses were available for typesetting and bulk printing, so multiple copies were handwritten and certified authentic by the notation “a true copy.” That note was recorded in red ink, and a copy bearing that notation was considered as valid as the original. The note appears on a number of the documents.

The affidavit of Major Samuel Colley shows the red-inked notations confirming it as a “true copy” of his statements.

The two most compelling items in the Linda Rebeck Collection of Sand Creek Documents are letters to Major Edward Wynkoop, attributed to Captain Silas Soule and Lt. Joseph Cramer, both of whom were present to witness the horrors of November 29, 1864. These letters, in particular, exerted overwhelming influence in Senator Campbell’s successful effort to establish the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. The full text of each appears in the committee’s published hearings as well as in other printed sources, including the Rocky Mountain News of September 15, 2000, just before the hearings began.

The letters, like other documents in the collection, do not appear in the original hand of their respective authors. Similarly, they do not appear to have been copied by Wynkoop, or even Samuel Tappan, who was also involved in the investigation. However, the handwriting styles are similar in both letters, indicating it is probable that a member of the Adjutant’s staff copied them.

Camp Weld Conference participants, Denver, September 1864. Left to right, according to historian David Halaas: (kneeling) Major Edward W. Wynkoop, Captain Silas S. Soule; (seated) White Antelope, Bull Bear, Black Kettle, Neva, Na-ta-nee; (standing) unidentified, unidentified, John S. Smith, Heap of Buffalo, Bosse, unidentified, unidentified.

Some mystery surrounds the question of why the affidavits were included in the official reports, but not the letters by Soule and Cramer. Both officers, along with Wynkoop, provided reports or testimony to both investigations, but none of the officers made reference to the letters. The only allusion to the letters appears in a report submitted by Wynkoop on January 15, 1865. They must have influenced Wynkoop, because his report references communications with officers and soldiers in which they described “the most fearful atrocities…women and children were killed and scalped…and bodies mutilated in such a manner that the recital is sickening.” Further, other details in the Soule and Cramer letters are corroborated.

Why were the letters not submitted as evidence? The answer may be easy to explain: Soule and Cramer wrote heartfelt expressions of anguish to a friend. Neither prepared their writing as official documentation for the US Army or the US Congress, and neither letter was acceptable as sworn testimony. The identity and motivations of the copyist are also mysterious. Perhaps Major Edward Wynkoop asked a fellow soldier to share the news in an unofficial capacity. How any of the documents found their way into the possession of rancher Mark Blunt is a third puzzle. As a veteran of the Second Colorado Cavalry and a Pueblo rancher who supplied Fort Lyon, Blunt was acquainted with the post’s officers. The details of his possession, however, remain obscure.

The letters written by Soule and Cramer, as well as the other compelling eyewitness accounts, provide a basis for understanding the Sand Creek Massacre as an unjustifiable attack on innocent Cheyenne and Arapaho villagers. Much as Soule’s and Cramer’s letters sparked government inquiries, private institutions such as Northwestern University, the University of Denver, and the United Methodist Church have committed to investigate and disclose their institutions’ roles in the Sand Creek Massacre as the 150th anniversary approaches. In 2012, the General Conference of the United Methodist Church, in consultation with the Northern Cheyenne Tribe, the Northern Arapaho Tribe, and the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, unanimously approved a resolution to appoint a research team to investigate the “involvement and influence in the Sand Creek Massacre of John M. Chivington, Territorial Governor John Evans, the Methodist Church as an institution, and other prominent social, political and religious leaders of the time.”

After conducting its own investigation, a special committee formed by Northwestern University issued a report on the complicity of Colorado Territorial Governor John Evans, a university founder and major benefactor, in May 2014. The report concluded that the governor’s foreknowledge of the attack was unlikely, but that he certainly helped create a climate of hostility to Cheyenne and Arapaho people, and defended and rationalized the massacre after the fact.

A committee appointed by the University of Denver, which Evans also founded and supported, has been charged with a similar inquiry. Its report is forthcoming as of press time.

Authors note: The authors thank Jeff Campbell, ranger and site historian, Interpretations Division, Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, for his insights into the Sand Creek documents and the work of Post Adjutants and other military and fort personnel. Gary L. Roberts and David F. Halaas’s essay about the Soule-Cramer letters for the winter 2001 Colorado Heritage appears as “Written in Blood: The Soule-Cramer Sand Creek Massacre Letters,” Western Voices: 125 years of Colorado Writing (Denver: Colorado Historical Society/History Colorado, 2004).