Story

All-American Ruins

Discovering the meaning of anemoia and reawakening the healing power of abandoned places.

Listen to Pfeil's companion podcast

The first time I poked around the abandoned dairy farm down the hill from my childhood home in Colorado Springs was in 1993. I was only six years old. When I figured out how to get inside, I immediately had this funny feeling, right down in my gut, as if I’d been there before. This wasn’t possible, of course, because the dairy farm, a gift to the Sisters of St. Francis of Perpetual Adoration from millionaire Blevins Davis, was out of use by 1980. In the thirteen years between its closure and eventual demise, the site became a popular destination for thrillseekers and trespassers.

That funny feeling in my gut was more than a strange, almost other-worldly familiarity; it also gave me a sense of safety, security, and serenity. Inside the barn or the grain silo or the aforementioned house, still full of dishes, furniture, clothes, and animals painted on the windows, I ran my fingers along the walls, and somehow, it was recognizable to me. I began to frequent the ruins of a time gone by, nestled neatly in the foothills of the Rockies near Colorado Springs, and it slowly transformed into my private sanctuary where I was shielded from the reality of the outside world. This unidentifiable sensation I felt actually has a name. It’s referred to as anemoia, “a deep feeling of nostalgia for a time one has never known.” C.S. Lewis championed a German term that also vaguely describes it, sehnsucht, “a yearning, wistful longing.” I also found someone online who coined the phrase vicarious nostalgia, which seems to fit the bill. Sort of.

Whatever this all-encompassing sensation was that I felt right down to my toes, it brought me peace, and I sought it out as much as I could. On every quest to the abandoned dairy farm, I found myself engaging in made-up conversations with imaginary characters who might’ve once lived there. These inventions of dialogue made me feel even closer to the place and time which I had never known or experienced. I don’t know how else to explain it. I felt as though I’d been there before—that I belonged there. With my imaginary friends, the dairy farmer, his wife, and their kids, I found kinship and safety and meaning. Consequently, the abandoned dairy farm became the genesis of an extraordinary, personal credence: that my imagination could exist not only as a place of wonderment and creativity but also as a place of great comfort and healing.

Arson took the life of my private sanctuary in 1994 when four teenagers burned the dairy farm to the ground. The remains were bulldozed, and overpriced, gaudy condos took their place. Though the physical space had been destroyed, the spiritual domain I discovered there seemed to linger in me. I carried those memories in my subconscious until May of 2020, when I woke up from a dream that I was back inside the dairy farm. That same funny feeling was still right down in my gut. It was the first time in months that I felt a sense of safety, security, and serenity. At that point, the COVID-19 pandemic had been raging for more than three months in the United States, and my germaphobe-centric anxiety had taken full control of my life. With the isolation wreaking serious havoc on my head and heart, and though I knew I wasn’t alone in the collective feelings of confusion, fear, and hopelessness, I still felt isolated. I lay in bed, staring at the ceiling, thinking about the abandoned dairy farm, and I wondered if there were any abandoned buildings near my current home in the Hudson Valley, New York. I hopped out of bed, did a quick Google search for “abandoned spaces near me,” and, as it turns out, they’re everywhere.

MWA Tuberculosis Sanatorium after the 1994 fire, which left only ruins behind.

I'd stumbled on a world I'd never heard of: Urban Exploration, or "Urbex" for short, is an underground community devoted to mini odysseys all over the world in search of the drudge and decay of once-occupied dwellings—and not just in urban areas, but in suburban and rural areas too. Most Urbexers aren’t arsonists; rather, they’re deeply respectful admirers of history, gatekeepers into the past who understand the significance of even the most unknown, unexplored spaces. Exploring abandoned spaces is, of course, a dangerous hobby and often comes with its own architectural, legal, and safety liabilities. Old buildings have often been compromised by time, and some abandoned places like mines were probably never all that safe to begin with. But as I devoured more information on this global company of misfits intent on seeing the unseen, unafraid to bend a trespassing rule or two, I couldn’t help but laugh. Apparently I’d been an unofficial Urbexer myself ever since I was six years old, traipsing about the abandoned dairy farm.

With my interest piqued, I began to scour the Internet, hoping to learn more about the abandoned dairy farm from my past, and I discovered that it had its own pandemic-related roots: tuberculosis. Yes, the disease that kills Satine (played by Nicole Kidman), the fallible heroine of Baz Luhrmann’s 2001 movie musical Moulin Rouge! Yes, the virus that afflicts Hans Castorp, the observant protagonist of Thomas Mann’s 1924 modernist novel The Magic Mountain. It was Mimi’s death sentence in Pucinni’s 1896 masterpiece La bohème, and it took the life of Claude Monet’s actual wife Camille, later depicted on her deathbed in Monet’s 1879 visual dirge “Camille Monet sur Son Lit de Dort.”

That tuberculosis.

As the Centers for Disease Control suggests (with a strangely excited tone), “[German physician] Johann Schönlein coined the term “tuberculosis” in 1834, though it is estimated that [the bacterium] may have been around as long as 3 million years!” The National Library of Medicine estimates the genus Mycobacterium (which causes tuberculosis) may have originated 150 million years ago. However long it’s been with us, “TB” is an infectious, highly contagious disease. An infected person’s chance of survival was extremely low until the mid-1850s when the first kind of treatment popped up in Germany: the tuberculosis sanatorium. Modeled after European mountain spas and resorts, sanatoria offered the “consumptive” (as TB patients were known) a chance to breathe fresh mountain air, bathe in sunshine, and take lengthy walks as part of an intense healing regimen that included protein-packed diets and relaxation.

After General William Jackson Palmer founded Colorado Springs in 1871, the city and surrounding area became a hot spot for “Go West” tourism, a gateway to the Rockies. Known for its year-round sunshine and dry climate, it seemed like the ideal place for sanatoria. They began popping up across the Front Range region, making Colorado “a most desirable destination for chasing the TB cure [in] the ‘The City of Sunshine,’” according to the Pioneers Museum’s City of Sunshine exhibit. Among the many sanatoria located in Colorado Springs, the Modern Woodmen of America Sanitorium became internationally recognized as one of the most restorative healing spots, due to its location in the shadow of Blodgett Peak.

Enter: the abandoned dairy farm from my childhood.

The dairy farm was originally erected as part of the much more sizable tuberculosis sanatorium, owned and operated by fraternal benefit society Modern Woodmen of America (MWA). From 1909 to 1947, the sanatorium essentially functioned as its own town, boasting a train station, power plant, reservoir, orchard, administrative buildings, an auditorium, 245 of the iconic “TB huts” (with their emblematic peaked roofs, resembling a tragic Christmas village, many of which you can still find all over the state), as well as the state’s largest dairy herd. One of the more frightening symptoms of tuberculosis is excessive weight loss, and as part of their extensive treatment, the more than 12,000 patients who passed through the MWA sanitorium community were encouraged to drink up to ten glasses of milk a day, provided exclusively by the bovine beauties at the dairy farm. This also wasn’t any old herd of cows. They were recognized nationally as one of the finest Holstein herds in the nation, having won dozens and dozens of prizes over the course of their existence. In fact, the herd had an international celebrity in the mix: Parthenea Nudine was an exceptional milk producer, who by 1932 had already pumped out over 186,000 pounds of milk, more than any other cow in the world her age.

I am enchanted by sites like the abandoned dairy farm from my childhood, places that look like they’ve been raptured, locations where I could once again time travel and feel that sense of serenity that I felt when I was a kid. The intentional act of getting lost has always been an important component of managing my emotional, mental, physical, and spiritual wellbeing: The way that the Modern Woodmen of America Sanatorium existed to manage the emotional, mental, physical, and spiritual wellbeing of its patients. In fact, in his Report to the Executive Council for the sanatorium’s operations from 1929-1932, Superintendent John E. Swanger passionately elaborates on the existence of the sanatorium: “But the paramount purpose of the Sanatorium is what should concern and interest every Modern Woodman. Why was it built… and known throughout the land as the great Hope Station of Humanity? … the care and treatment of Beneficial members of the Society, afflicted with tuberculosis, so as to give them the best possible chance to overcome the disease and live.”

It isn’t lost on me that, in a different pandemic, a century later, the intentional mission of the Modern Woodmen of America Sanatorium has lasted, in its own way, and helped me overcome a different disease, spiritually, and live. For nearly three years, I’ve ventured out to over fifty different abandoned spaces in thirteen states and three countries: military bases, factories, churches, bowling alleys, resorts, motels, arcades, psychiatric facilities, movie theaters, and houses. What started as a way to pass the time safely evolved into a salve for my mental health and a realm for my creativity to explode. I began to write about my experiences in each location, not just about each space itself, its architectural narrative, or the sordid history behind it, but also about what was going on inside my head as I wandered through each one. The more I explore, the more I realize that I’ve been reconnecting with my childhood self and imagination that became a healing realm all those years ago at the abandoned dairy farm.

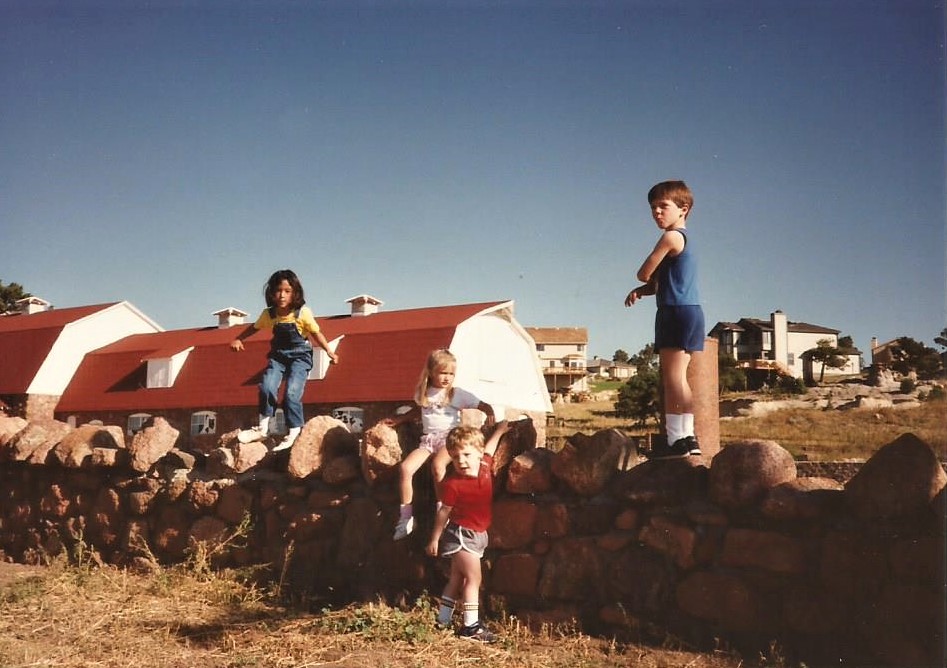

Blake (in red, second from the right) at the MWA tuberculosis sanatorium, c. 1992.

What’s evolved out of that childhood fascination has been nothing short of extraordinary, and I invite you to experience it too. All-American Ruins is a multimedia travelog in which I recount my experiences exploring abandoned spaces across the United States and reimagine them via written, photographic, audio, and cinematic storytelling. Along the way, All-American Ruins asks critical questions about American history/culture, community, capitalism/economics, the environment, and mental health while encouraging folks to activate their imaginations as a tool for healing. You can join me inside these dreamscapes that blur the lines between fact and fantasy by reading the blog, watching the HUDSY series, or listening to the immersive podcast, including a special bonus episode produced exclusively for this collaboration with History Colorado.

I’ve been able to bear witness to humanity and honor the sometimes soiled American past, the untold stories of regular, everyday folk just like me, forgotten histories that live inside the walls of each abandoned space where lives were once lived, pain was once felt, and love was once expressed. It’s grounded me in a way that I can’t explain except through immense gratitude and creative expression and the sheer willingness to keep showing up for that magical, funny feeling, right down in my gut, the same one that brought me the safety, security, and serenity I felt all those years ago at an abandoned dairy farm in the foothills of the Colorado Rockies.