Story

Colorado's Forgotten Diversion Dilemma

The Colorado-Big Thompson project was at the center of a fierce debate that shaped Americans’ relationships to their national parks.

Few visitors to Rocky Mountain National Park will ever visit the East Portal. And why would they? Located just a few miles south of Estes Park, the East Portal contains no views of snow-capped peaks or broad valleys teeming with wildlife. Instead, it is framed by low-lying hills and power lines that draw energy from water flowing out of an odd-looking tunnel and pooling into a nondescript reservoir. It is, compared to some of the area’s more breathtaking vistas, an unremarkable landscape with seemingly little connection with the one drawing hordes of sightseers and adventurers into nearby Rocky Mountain National Park.

Yet appearances can be deceiving. Even while unsuspecting visitors explore one of the nation’s iconic landscapes, the tunnel is redirecting the natural flow of the Colorado River underneath the Rocky Mountains and out the East Portal, en route to users across Northern Colorado. Completed in 1944, the Alva B. Adams Tunnel forms the critical undermountain link in the Colorado-Big Thompson Project (C-BT), a piece of hidden infrastructure that, as you read this, is supplying water to farms and municipalities across the Northern Front Range.

Despite the C-BT’s importance, few Coloradans consider it when they turn on their showers or dig into a plate of seasonal Front Range veggies. But from 1933, when it was proposed, until 1937, when Congress approved the project, the C-BT inspired passionate support and vitriolic opposition from a range of interest groups that Coloradans today would recognize immediately.

The supporters’ side included farmers, industrialists, local boosters and scientists. In the midst of a decade characterized by drought and depression, they argued that C-BT water would rescue the region’s agricultural economy from collapse by the simple act of moving water from a region that possessed it in comparative abundance to one desperately needing it.

On the other side were conservationists and nature-lovers who complained bitterly that the Adams tunnel would desecrate Rocky Mountain National Park. They wrote protest letters, pamphlets, and editorials, and appeared before hearings in Congress and the Department of the Interior. Some complained that the tunnel was a commercial intrusion into a national park. They excoriated the business interests and town developers for wanting to scar a landscape set aside for preservation and the enjoyment of the American people. They worried that it would set a precedent for the exploitation of other national parks. Other conservation-minded opponents argued that the tunnel violated the need to preserve wild places for the sake of wilderness. To remove water from the woods and pump it onto the plains, they said, would be to fundamentally alter fragile western ecosystems. The war of words reached such a fever pitch that historian Donald Swain says that the C-BT offered one of the most consequential examples of water project opposition in American history.

It’s not news that water is central to life, and that’s especially true here in arid Colorado. Access to water and the sanctity of public lands—issues that defined the fight over the Colorado-Big Thompson Project—resonate perhaps more than ever as climate change challenges our ability to engineer around aridity. Vitriolic discussions over water use for agriculture, for growing cities, for energy development, and for recreation are happening with just as much ferocity today as they did nine decades ago. Colorado’s central urban strip continues attracting residents at a breakneck pace, in part due to the outdoor lifestyle afforded by such close access to public lands. Cities on the Front Range are still buying C-BT water rights from farmers on the Western Slope, even as the oil and gas industry injects some of that same water thousands of feet into the earth to be lost to underground hydraulic fracturing.

No matter what the use, hardly anybody gets to use water in Colorado without a fight. It’s as true today as it was in 1933, when the Colorado-Big Thompson project threatened to forever change one of the nation’s most prominent protected landscapes: the snowy peaks and verdant valleys of Rocky Mountain National Park.

Tyndall Glacier in Rocky Mountain National Park. Meltwater from the park’s many glaciers feed water needs across Colorado.

Origins of Conflict

Ever since gold’s discovery near Denver in 1858, Front Range residents have far outnumbered those living in the western half of the state. But eighty percent of the state’s precipitation falls west of the Continental Divide, creating a problem for the many urban Front Range residents who live in a much drier climate. So, as Colorado’s population grew throughout the late 1800s, it did not take long for the water-starved majority to devise methods for circumventing geographic barriers.

Moving water underneath or around a mountain from one watershed to another—a process called transmountain diversion—was nothing new when the C-BT controversy emerged during the 1930s. The largest of these early projects, called the Grand River Ditch, transported water in an unlined ditch and wooden flumes to Fort Collins through an area that would eventually become part of Rocky Mountain National Park. In 1904 the Bureau of Reclamation, with sights set on a much larger diversion, suggested damming Grand Lake and then constructing a twelve-mile tunnel that could fill the ditches of Northern Colorado farmers. However, high construction costs and complex engineering tabled the project.

As water users created precedents for gravity-defying projects, conservationists developed a reputation for opposing them. The most notable example involved San Francisco’s 1907 proposal to dam Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy Valley for water and power generation. Though Congress eventually approved San Francisco’s application, the project galvanized opposition from conservation organizations such as the Sierra Club. Protesters argued that national parks existed for the beauty and enjoyment of the nation and its people and that commercial development violated those core principles.

Politicians and federal officials took note of this growing tension between water developers and conservationists, spurring them to craft laws and principles for human activities in national parks. When Congress established Rocky Mountain National Park in 1915, Franklin Lane, Secretary of the Interior, sought to ensure the legality of water projects within park boundaries. As a former attorney for the city of San Francisco, Lane played a critical role in the bruising battle over damming Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy Valley. Head of the vast Interior Department, which oversaw both national parks and the water project builders at the Bureau of Reclamation, Lane worried that national park designation might present too many obstacles to water development. So, the wily attorney inserted the following language into Rocky Mountain’s founding document: “The United States Reclamation Service may enter upon and utilize for flowage or other purposes any area within said park which may be necessary for the development and maintenance of a Government reclamation project.”

That language offered a legal justification for diverting water through the park. However, the following year Congress muddied the waters a bit. In 1916, legislators approved the Organic Act, a lengthy bureaucratic document which, among other things, established the National Park Service. According to the Act, that new agency’s mission was to “conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” For conservationists and park service employees, the Organic Act was a manifesto for resistance to all kinds of commercial development. Certainly, they reasoned, dynamiting a tunnel through the length of Rocky Mountain National Park would impair the public’s enjoyment and break the illusion of standing in an untouched wilderness.

Circumstances brought the potential of a massive hole through the national park into public consciousness during the 1930s as Colorado suffered through drought and economic collapse. As crops dried up, an array of Northern Colorado groups came together to request that the federal government investigate the feasibility of blasting a tunnel that could divert Colorado River water through Rocky Mountain. These included five counties, all but one member of Colorado’s Congressional delegation, editors of each of the region’s major newspapers, a majority of local elected officials, and Front Range farmers. In 1934 the Bureau of Reclamation agreed to conduct engineering studies in advance of a project proposal. Reclamation Commissioner John C. Page followed up with a letter to Acting Park Service Director Arthur Demaray requesting entry. Demaray refused.

In a formal letter of denial addressed to Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, Demaray penned the opening arguments in the fight over the tunnel. He complained that engineering studies taken in the park would require test drillings, resulting in “scars” and “unsightly debris.” According to Demaray, such surveys and any tunnel which might be built required constructing access roads and trails to “places where roads and trails should not rightfully go.” Demaray’s letter rhetorically transformed a local irrigation project into a national issue, pointing out that conservationists had fought to keep national parks “inviolate from such projects,” and that the proposed survey could be “an opening wedge in a hard-won wall of protection which surrounds our park system.” In response, Ickes, a noted supporter of national parks, nonetheless authorized the engineering surveys, believing that he was obligated by the fact that water diversion projects were embedded in Rocky Mountain’s founding legislation.

Conservationists Make Their Case

Following Ickes’ approval, conservation forces quickly mobilized in opposition. Organizations such as the Sierra Club and the Wilderness Society mailed flyers to their supporters and placed ads in newspapers throughout the country. Individuals then sent dozens of protest letters to federal agencies. While some letters appear entirely original, others were variations on templates developed by conservation organizations. Many of these letters are housed at the Broomfield branch of the National Archives. In addition, nationally recognized figures in the National Park Service, directors of conservation organizations, and scientists wrote op-ed pieces in magazines and newspapers.

Their strident opposition came during a period when national parks were drawing patrons in record numbers as many sought escape from the crushing economic collapse of the Great Depression. As the federal government considered the Colorado-Big Thompson Project between 1934 and 1937, annual visitation to Rocky Mountain National Park nearly doubled to 650,000. This was motivated in part by the recently built Trail Ridge Road, which offered stunning views to motorists as they traveled across the Continental Divide between Estes Park and Grand Lake.

The arguments made by conservationists in opposition to the tunnel probably resonate with today’s Coloradans who enjoy recreating in the state’s public lands. Letter writers universally expressed concerns that a massive engineering project inside park borders would mar the scenery and set the stage for similar projects in national parks elsewhere. Most protesters extolled the uniqueness of the landscape inside Rocky Mountain National Park, arguing that it was the highest expression of nature and the people of the nation had afforded it the most stringent degree of protection available at the time. Consequently, only development that enhanced the scenery and natural beauty of the parks should be allowed. Many made this distinction clear when they offered support for farmers’ need for water, as long as the conduits that delivered the resource were outside of the park boundaries. Other writers expressed concerns about the declining number of wild places in America, arguing that national parks offered the best opportunity for humans to have unimpaired encounters with wild nature. Finally, many protesters viewed Rocky Mountain through patriotic lenses. They claimed that national parks existed for every American and that a tunnel would prioritize local interests over national ones.

Members of the Colorado Mountain Club looking west towards Grand Lake from on top of the Continental Divide. Many outdoor-oriented activities opposed the C-BT project, fearing environmental damage and the intrusion of commerce into wild Western landscapes.

Among the varied written protests, none received more attention than a 1936 pamphlet titled, “A Protest of Conservation Organizations Against the Exploitation of Rocky Mountain National Park.” Its signatories included the most notable conservation organizations of the 1930s, including the Wilderness Society, the American Forestry Association, The Izaak Walton League, the Sierra Club, and the National Parks Association. They argued that the tunnel “violates the most sacred principle of National Parks, namely, freedom from commercial or economic exploitation,” and that if approved by Congress it would “establish a precedent for the commercial invasion of other parks.”

The most likely author of that pamphlet, Robert Sterling Yard, took the protest a step further, by arguing that the proposed tunnel was an assault on one among a dwindling number of wild places in America. By the 1930s, Yard was in a strong position to make this claim. As the head of the National Park Service’s Educational Division from 1916-1919, he promoted national parks as America’s “scenic masterpieces” which, like great art, had the potential to build a more enlightened public. For Yard, irrigation projects in national parks were akin to defacing a Rembrandt painting. So, during the 1920s, he directed much of his energy toward fighting water projects in parks such as Yellowstone, Glacier, and Grand Teton.

During the same period, Yard became increasingly concerned that parks such as Rocky Mountain were being overrun with tourists who seemed more interested in driving through than in enlightening their minds. Though not the same as boring a hole through the mountain or clearcutting a forest, Yard regarded the assault of asphalt and autos as commercial invasions just the same, since they encouraged visitors to rapidly consume landscapes while disregarding their geologic or biologic value. For Yard, blasting holes through the park and the proliferation of roads were two sides of the same coin. Both compromised the core mission of national parks.

By 1930, Yard concluded that the best way to preserve the scientific and scenic qualities of the nation’s iconic parks was to promote vast roadless tracts called wilderness areas. So, in 1935, even as the first tunnel engineering surveys were getting underway, he helped to form the Wilderness Society. According to the Society’s first publication, wilderness areas are “virgin tracts in which human activities have never modified the normal processes of nature. They thus preserve the native vegetation and physiographic conditions which have existed for an inestimable period. They present the culmination of an unbroken series of natural events stretching infinitely into the past, and a richness and beauty beyond description or compare.” In short, Yard and his allies argued that the proposed tunnel would do more than deface park scenery; it would violate the fundamental laws of nature. To restore nature’s balance, Rocky Mountain needed less construction and more wilderness.

The most common protest expressed by Robert Sterling Yard and his conservationist allies was that the C-BT prioritized local needs over national ones. Yard’s Wilderness Society colleague Bernard Frank expressed that sentiment when he wrote that the national parks were areas “dedicated to the service and enjoyment of the people of the United States as a whole and not to any narrow interests of any particular locality.” Frank later emphasized that it would be the “primeval qualities” of the park which would be compromised should local “narrow interests” prevail. Letter writers Laurel and Lincoln Ellison of Montana cited national interests as well, claiming that the country’s need for outdoor recreation in “unspoiled nature…should take precedence over such local demands for irrigation and water power.” In an editorial in the New York Times, former National Park Service Director Horace Albright chimed in with similar reasoning. He cited the five million tourists who had visited Rocky Mountain National Park since 1915, the 550,000 travelers who entered the park in 1936, and the seven-and-half million dollars spent by park visitors, arguing that the C-BT would destroy “the natural charm of the landscape.” He concluded that “private interests should give way to the general good.”

The arguments against the tunnel put forth by conservationists resonate in Colorado today. Presently, there are forty-two wilderness areas in the state, most of which have been designated since Congress passed the Wilderness Act in 1964. Each wilderness is intended to minimize human impacts by restricting all forms of mechanized travel. In fact, four of these wilderness areas border Rocky Mountain National Park. Moreover, much of the park has been managed as wilderness since 1974. At the same time, the visitor’s desire to motor through has only increased. It took twenty years for total park visitation to hit the five million mark. Today, nearly that many people tour the park by car annually. These numbers are especially evident when spontaneous traffic jams occur at sites where elk or moose grace the roadside. Whether those scenes support or violate the conservation mission of Rocky Mountain remains the subject of sometimes heated debate.

Making the Case for the C-BT

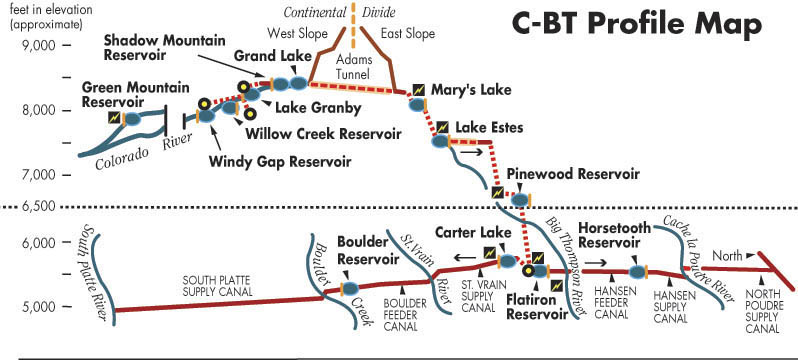

Let’s return now for a moment to the East Portal, where Colorado River water flows out of the Alva B. Adams Tunnel and exits Rocky Mountain National Park. From there the water plunges 2,900 feet through twelve reservoirs and over one hundred miles of canals before it is available to farmers, municipalities, and businesses in Northern Colorado. In 1937, the intended beneficiaries of that water needed to address some of the arguments made by conservationists, even as they directed the debate away from the sanctity of national parks and toward economic benefit. Would the C-BT bring enough benefit to justify its price tag, estimated to be $44 million in 1937? To gain Congressional support and to counter conservationists’ arguments that the Adams Tunnel would desecrate a national treasure, they had to make the case that the C-BT would bring substantial economic benefit to the nation.

Among the many people clamoring for the C-BT, Ralph Parshall stands out. While Parshall was not the loudest voice in the debate, his arguments and evidence were perhaps the most convincing. A resident of Northern Colorado himself, Parshall graduated at the top of his engineering class at Colorado Agricultural College (CAC—the forerunner of Colorado State University) in 1904. After completing a master’s degree at the University of Chicago, he was hired by his alma mater in 1907. As a professor at CAC, Parshall engineered reservoirs, dams, and irrigation canals in Northern Colorado. Then, in 1913, Parshall took a position as an irrigation engineer with the USDA’s Bureau of Agricultural Engineering where he worked for the next forty years. While at the USDA, Parshall’s office and lab remained on the campus of CAC where he collaborated with students and faculty throughout his career.

Ralph Parshall checks on one of his flumes.

By the time the C-BT came into public consciousness in the 1930s, Parshall was a well-known figure due to his namesake invention, the Parshall Flume. That innovation made water distribution to agricultural users more equitable wherever it was installed as it increased measurement accuracy in canals and ditches by up to thirty percent. This helped farmers to know how much water they were receiving and prevented water users from taking more than their allotted shares. By 1935, Parshall had also distinguished himself as a pioneer of snow surveys and for developing devices to remove debris from irrigation canals. Combined, Parshall’s work enabled farmers to plan their operations effectively since they could predict the quantity of water available to them. He also earned the respect of individual farmers since he frequently supervised the design and installation of his inventions on their land. Consequently, when the USDA needed a knowledgeable and well-respected figure to prepare an economic analysis of the C-BT, Parshall was a clear choice. He possessed an unshakeable reputation as a skilled irrigation engineer with intimate knowledge of the Northern Colorado landscape.

Parshall’s Agricultural Economic Summary Relating to the Colorado-Big Thompson Project came out in January 1937. It contained a dizzying array of economic data collected by Parshall and his team of researchers. They compiled statistics on value, acreage, water rights, and loan status for every irrigated farm in the region. They also collected precipitation records, breaking down the quantity of water available for every irrigation district and mutual irrigation company in the C-BT’s service area. Parshall went to pains to show how C-BT water would be an affordable and effective solution to the region’s water woes.

Even as the data spoke loudly, Parshall’s applied understanding of Northern Colorado’s irrigation-dependent farmers amplified statistics. Aware that a massive Reclamation project might be viewed as a government handout in the midst of the Depression, Parshall characterized the region’s farmers as “hardy, self-reliant American farmers and townspeople” who needed additional water to “stabilize the present economic achievement and make secure the possibilities of future progress.” In a nod to popular Depression-era programs, Parshall stated that the guarantee of sufficient water would be like “social security” for existing farmers, enabling them to gain the same security in their later years that working class Americans received. Seeking to demonstrate that the C-BT was a difference maker, Parshall argued that its greatest value would be that its flows would be available late in the growing season, when some water users ran out of water and when an additional application of water to high value crops might make the difference between breaking even and crushing debt. In stark financial terms, Parshall stated that irrigation provided $64 million worth of property value to Northern Colorado, a region valued at $200 million. This additional property value resulted in local, state, and federal taxes that could be invested in schools, infrastructure and economic development.

In Parshall’s analysis of the seventy years of irrigation in the region prior to 1935, he concluded that land values were high because of “greater assurance that crops will be produced and the possibility of growing crops of higher value than could be grown without irrigation.” According to Parshall, the economic gains made possible by irrigation were far higher than the C-BT’s estimated $44 million price tag. But Parshall extended his analysis far beyond the farm, arguing that prosperous Northern Colorado farmers supported the growth of local businesses, increased railroad traffic, enabled more construction, strengthened financial institutions, and made possible the sort of increased highway traffic that carries with it travelers and tourists eager to spend their money in local businesses.

Knowing that C-BT opponents might argue that the nation was suffering from too much agricultural production, Parshall turned that caution on its head by claiming that more water would shift agricultural production away from crops grown in surplus and toward crops not grown in sufficient quantities. For example, he argued that wheat, whose national supply had far outstripped its demand, was a crop of choice in Northern Colorado only when water was in short supply. By contrast, sugar beets, the most lucrative crop in the region, demanded more water than wheat. Yet, the majority of the nation’s sugar was imported. Consequently, according to Parshall, increasing Northern Colorado’s water supplies would push farmers to grow more beets and less wheat, thus aligning the nation’s agriculture more closely with consumer demand and reducing dependency on foreign sugar. Parshall concluded that the C-BT would support self-reliant, productive Americans who created real economic value that extended to the nation. In short, the C-BT was an overwhelmingly good investment.

No entity agreed more with Parshall's assessment than Great Western Sugar, the nation’s largest supplier of domestic sugar and Northern Colorado’s most important economic driver. Great Western’s factories depended on the same water as the farmers who sold the company its beets. Moreover, as a late arrival to the region, its junior rights weren’t secure. In fact, during the 1934 refining campaign, the company’s ditches ran dry, and it had to beg local irrigation companies for water to complete its operations. So, the company always craved more water, either by cultivating relationships with its growers or through projects such as the C-BT. To energize local C-BT support, Great Western made liberal use of its grower magazine, Through the Leaves. In it the company published reader-friendly versions of scientific articles showing how their beet harvests would increase with just a little more water. In 1936, the company said it more explicitly: C-BT water would result in an average annual income increase of $400 per grower.

To make the national case for the C-BT, Great Western employed lobbyists in Congress. This was nothing new since the company had always pressured legislators to enact high tariffs against foreign sugar. In 1937, those lobbyists shifted from taxes to water. Great Western also took to the airwaves to make its case. In cooperation with other western beet sugar companies, it paid the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) to do a series of short radio programs titled, “Sugar Beets Tell the World.” The broadcasts emphasized how sugar beets grown in the irrigated regions of the West contributed to the American economy, providing figures on grower income, railroad shipments, resources used in refining beets into sugar, and the varied ways beet sugar was consumed. To hear Great Western tell it, beet sugar was essential to the American economy, and the C-BT was essential to the beet sugar industry.

Ultimately, the arguments made by Ralph Parshall, Great Western Sugar, and supporters of the C-BT proved successful. After spirited debate in June and July of 1937, Congress passed bills approving the project and authorizing an initial $900,000 in funding. The following year, prospective water users signed a contract to pay a maximum of $25 million over the course of forty years for the project, with the remainder of the costs being paid for by hydroelectric power generation. That $25 million cap turned out to be quite a bargain. When Reclamation finally completed the C-BT in 1957, total costs had soared to over $160 million.

Conservation, Cattle, and Water

The completion of the C-BT in 1957 heralded shifts in Northern Colorado’s agricultural landscape that would make the region look familiar to the present-day observer. Former Colorado Agricultural Commissioner Don Ament recently reflected on some of these changes while talking about his family’s long history in the region. During the 1930s, Ament’s family emphasized sugar beets on their irrigated lands near Sterling. As Ament transitioned into farming for himself in the 1950s and 1960s, he shifted from sugar beets to corn. As he explains, the C-BT played a critical role in the move to corn, a crop that required more water. More importantly, Ament’s well-watered corn found a ready market in the growing commercial cattle feeding industry. By 1970, Northern Colorado possessed the world’s largest collection of commercially fed cattle, and the region’s farmers cultivated most of their feed. Today, this is still true. As Ament points out: “two-thirds of Colorado’s agricultural output is livestock, primarily cattle.” Most of those animals are fed with corn from farms irrigated by C-BT water.

If the C-BT’s story in the 1960s and 1970s revolved around agricultural possibilities through increased water, the project’s story today is about growing municipal demands for water. During the 1950s, Northern Colorado possessed a population of fewer than 200,000 mostly rural residents. The 2020 census shows that the region’s population today is well over one million, with the majority concentrated in cities within thirty miles of the Front Range. Each of the cities receives an allocation of C-BT water for residential use. In support of this shift, the Bureau of Reclamation built new storage reservoirs and increased the capacity of existing ones, while extending water supply lines to previously underserved areas. This has led to increased tensions between municipalities and farmers over selling water rights. During the last thirty years, Northern Water—the agency that administers the C-BT—agreed to supply water to cities outside of original C-BT boundaries such as Broomfield, Superior, Lafayette, and Louisville. Other cities, such as Thornton, have been more aggressive. In 1986, to accommodate aggressive growth, it paid $55 million to buy up more than 20,000 acres of farmland and the associated water rights in Weld and Larimer Counties. All of this adds greater pressure to conserve remaining supplies.

One of Monfort of Colorado's feedlots, ca. 1970. Its pens could hold up to 100,000 steers.

For conservationists, the unsuccessful fight to block the construction of the Alva B. Adams Tunnel through Rocky Mountain National Park turned out to be just the first in many battles over water projects within the Colorado River watershed. During the early 1950s, Congressional legislators proposed a series of large-scale projects called the Colorado River Storage Plan, to be constructed for irrigation, power, and flood control at various locales along the river. The most controversial piece of the plan involved constructing two dams along the Green River, within the boundaries of Dinosaur National Monument. In opposition, conservationists, led by the Sierra Club, undertook a massive publicity campaign that successfully removed the dams from the bill. However, it came at a cost as conservationists made a deal to withdraw their opposition to another project dam in a little-known area of sandstone cliffs rich in Native American artifacts known as Glen Canyon. In 1963, that dam was completed creating Lake Powell, which dams the Colorado, San Juan, Escalante, and Green Rivers. Presently, drought, climate change, and water demands have reduced Lake Powell to one-quarter of its capacity, prompting some conservationists, scientists, and others to call for tearing down the dam holding it back.

If there is a single thread that ties together the water and conservation issues of the 1930s with those of the present, it is that the process of moving and storing water is value-laden. For 1930s farmers in Northern Colorado C-BT water was money, since accessing sufficient water at a reasonable price during the Depression would support increased crop production. For conservationists, the cost of the water was too dear, since it would defile one of the most iconic landscapes in America, setting a precedent for the commercial exploitation of other national parks. Both sides tried to answer questions about the relative value of our natural and scenic resources. Those questions are as pertinent today as they were back then.