Story

More Than Ephemeral

Preserving a Powerful Story of Resilience and Family, One Pint at a Time

At Ephemeral Rotating Taproom, the beers are always changing, but one family’s story of rebuilding in the aftermath of injustice is a lasting legacy.

When thirsty patrons step into Ephemeral Rotating Taproom in Denver‘s Skyline neighborhood, they find, as the name suggests, a here-today-gone-tomorrow selection from the best breweries around Colorado and the country. On a recent winter weekday, the stylish wooden handles of Frisco’s Outer Range Brewery (emblazoned with the slogan “Leave the Life Below”) occupied most of the twenty-four taps on the wall behind the bar as locals filtered in after work to meet friends and catch up over a pint.

But when Derek Okubo steps through the door and orders a pint, he tastes something else: his family legacy. Ephemeral is the recent incarnation of Ben’s Super Market, a longtime neighborhood anchor operated by Derek‘s grandparents. “This store, for our family, this location, is symbolic of the determination and resilience of my grandparents, of the restart of our whole family,” Derek explained over beers at Ephemeral.

Ben and Susan Okubo in the 1920s, around the time they were married in Los Angeles.

During World War II, Derek’s grandparents, Ben and Susan Okubo, who had immigrated to the United States from Japan, were forcibly removed from their home in Los Angeles and sent to the Amache Internment Camp near Granada in southeast Colorado. President Franklin D. Roosevelt set their displacement in motion when he signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, mandating that all people of Japanese ancestry living along the West Coast—approximately 120,000 men, women, and children, American citizens and immigrants alike—be removed from the region. The Okubos were forced to sell their store in the Eagle Rock neighborhood of LA. “They almost gave it away,” recalled their son, Henry, a young teenager at the time who said that his parents had accepted a price that barely covered the cost of the new butcher’s showcase they had just installed.

In a 1994 oral history archived at History Colorado, Henry recalled that his parents, foreseeing that they would be forced from their homes, quickly moved the family so that they would be able to evacuate together with his grandfather, aunt, and uncle as the government carried out removals one area at a time. In the summer of 1942, the Okubos were sent to the hastily established assembly center at the Santa Anita horse racing track. “We were one of the fortunate ones,” Henry explained matter-of-factly, “because our barracks were in the parking lot instead of the stables.” They lived at the assembly center until September, when they were put onto a train heading east. Henry remembers that on the long journey they were ordered to lower the shades over the windows every time they pulled into a station: “Either they didn’t want the people there to see in or they didn’t want us to see out—I don’t know which.”

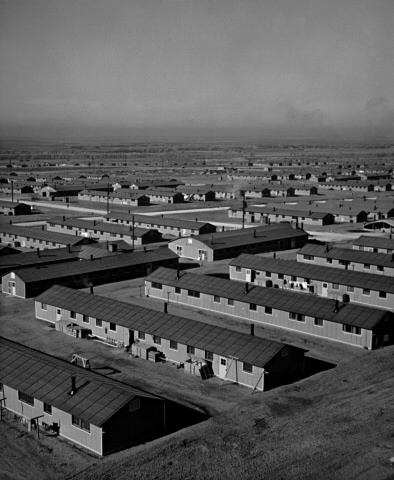

When the family arrived at the train station in Granada, then (and now) a small agricultural community on Colorado’s southeastern plains, the window shades couldn’t hide the reality of removal anymore. They were met by armed military policemen and escorted to their new home, the hastily constructed prison camp that officials referred to as the Granada Relocation Center, but everyone else commonly called Amache. The Okubos were ushered to barracks on block 10H, a single room bounded by timber-framed walls lined with tar paper. Ben, Susan, and their three children (two more would be born at Amache) were assigned the room next door to their relatives. It would be their home for the next three years. They were among the more than 10,000 people incarcerated at Amache during the war.

Henry’s memories of life in the prison camp are scoured by the windblown dust and snow that seemed constant. It gusted across the plains and whipped between the long, low-slung wooden barracks. And it blew through the cracks in the window sills, filling the dormitories with dust and, in the winter, dulling the effectiveness of the pot-bellied stove meant to warm the poorly insulated rooms. But Henry remembers days spent fishing and swimming with friends—the guards looked the other way when the children took the most direct route to the water, slipping over the fence surrounding the camp rather than going through the front gate. Henry excelled at the camp’s high school—he recalled that his math teacher had been a professor at Stanford—and with nothing much else to do he took classes year round, allowing him to graduate a year ahead of schedule.

Ben Okubo worked in the mess hall and later on the camp’s police force. During the growing season, he joined other men in the camp working on local farms, picking sugar beets and cutting broom corn. As the war wound down, the US government conceded that men and women of Japanese ancestry it had sent to the camps were not a threat to the nation’s security, and the people confined at Amache were freed. But for Ben and Susan, like many who had been sent to the camps, the lives they had made before their incarceration were gone. “They couldn't go back to LA because they didn't have anything to go back to,” explained Derek Okubo. Even the few valuables they had left behind, stored in a Buddhist temple, had been looted during the war. “And they couldn't afford to go back there either,” Derek continued, “because, you know, when they were released, they got $25 and a bus ticket to start their lives over again.”

“They left Amache with nothing,” Derek says.

Instead of going back to LA, they went to Denver. In the summer of 1945, Ben went ahead of the family to find work, securing a job in a market. Henry followed him and was employed in a warehouse. Soon Ben was able to purchase a house for the family to live in at 29th Avenue and Arapahoe Street in the city’s Five Points neighborhood, a historically Black community that many Japanese American families found more welcoming than other parts of Denver in the years after the war.

New arrivals disembarking from the train onto school buses waiting to take them to Amache.

Henry started classes that fall at Colorado A&M (Colorado State University in Fort Collins today), but he couldn’t continue his studies after he realized how much his family was sacrificing for him to attend college. “He came home one day after class and he found his younger sisters and his parents eating peanut butter for dinner because they were sacrificing, you know, saving to send him to school,” said Derek. “And seeing his younger siblings eating peanut butter for dinner broke his heart.” Instead of school, he convinced his father to take him to sign up for the Army. He was stationed in Japan, and sent a portion of his pay back home to support the family.

Eventually, by 1951 the family pooled enough money to purchase an old Piggly Wiggly grocery store on the corner of 28th Avenue and York Street. The location, with a bus stop out front, several churches nearby, in one of the most diverse areas of the city, seemed ideal to Ben, and he got to work remodeling the 1894 brick building for business. The final touch was installing large signs over the door—one facing each way on the corner—proclaiming the establishment as Ben’s Super Market in hand-painted blue and gold letters.

Ben’s Super Market created a foundation upon which the family rebuilt their lives. The store quickly became part of the fabric of the neighborhood, and the Okubos—Ben, Susan, and their five children who all worked at the store—went out of their way to serve their community. “People would come over to the house and knock on the door and say, oh, they needed milk or whatever and the store was closed,” said Derek, explaining that his grandfather was always willing to help out his neighbors. “He'd come over here and open up and get it for them.”

After his military service, Henry returned to Denver and finished school at the University of Denver on the GI Bill and launched into a career as a successful aeronautical engineer. Neither he nor his parents were eager to talk about their time at Amache, as Derek learned when he asked his grandmother about it one day. “I asked her about the camp, and I saw a look come over her face that I'd never seen before. It was one of pain and disgust and anger. I mean, just this thing that I had never, ever seen. And she just paused and shook her head and got up and left the table.”

But over time, Henry and his wife Aiko decided they had to speak out for the sake of their children. Derek remembers being called racist slurs by a PE teacher at his Littleton grade school, but his parents were reluctant to speak out until another teacher called his brother a liar for mentioning the internment camps. “His teacher said, ‘That never happened. You’re a liar.’...And I remember my dad, in the conversation at the dinner table that night, my dad said, ‘Well, I guess we're going to have to talk about it.’” After speaking with the school’s principal, who was supportive, Aiko came to speak with students about her experience at the Minidoka internment camp in Idaho. And Henry started sharing about his experience publicly as well. As Derek remembers it, “for a long time they were the only ones in all of Colorado that really spoke about it, because it was so painful and so the media would always go to them for stories about the camps.”

Henry told his children that life in the camps was perched on “a fine line between hope and despair on a daily basis.” It’s a sentiment that resonates with Derek still: “I can imagine my grandparents trying to be hopeful for the kids…but inside dying, just not knowing what the future held, what was going to come—and knowing what they had lost and that they were stuck in this camp because of their race by their country that they had come to, that they wanted to be a part of, and then the country sticks them in a prison camp because of their race. So that all was part of that despair.”

Eventually, in the early 1980s Henry and some friends who had been in Amache with him began leading an effort to preserve the site of the camp and commemorate the stories of those who had lived there. Several years later, in 1988, President Ronald Reagan would apologize on behalf of the nation to those who the government had imprisoned “without trial, without jury...solely on race,” calling it a “grave wrong” in which Americans gripped by wartime fear had forgotten our “commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law.” He signed a bill providing modest financial reparations to those who had been imprisoned while noting that “no payment can make up for those lost years.”

But in southeast Colorado, remembering and ultimately memorializing Amache was slow work, progressing only as quickly as survivors of the camp and residents of Granada built relationships with one another. When Henry died in 2002, Derek carried on the effort in his father’s place. Over the years, more residents of Granada have embraced the need to preserve and share the story of what happened at Amache. Today a museum in town is filled with items donated by families whose relatives had been imprisoned at Amache and is staffed by students from the local high school, all organized by the school’s history teacher, John Hopper. And last year, President Biden signed an act making Amache a National Historic Site that will be managed by the National Park Service.

As the president was elevating Amache’s status in the nation’s official memory, Shannon Lavelle and Weston Scott were busy remodeling Ben’s Super Market—Ben and Susan had sold the business in the early 1960s, but the name lived on—into a new community gathering place. And when they learned about the history behind the name, they wanted to honor the Okubo family legacy in that place. Derek recalls first meeting the new owners: “My sister and I came over and met with them, and we…talked about my grandparents and their history. And I just expressed my gratitude. And Shannon expressed her relief because she wasn't quite sure how we would respond.”

Today the original hand-painted “Ben’s Super Market” sign greets Ephemeral’s patrons, prominently positioned above a selection of grocery staples and other provisions that recall the store’s history as a neighborhood grocer. “I was so grateful that they would feel compelled to honor the history and to use my grandpa's sign still in the bar,” says Derek. “I think my grandparents are smiling. I sincerely do. Because, one, the building is still here. It's still a gathering place for people. They loved people. I think that they are being remembered is icing on the cake. I don't think they would expect that. I didn't expect it.”

Ben’s Super Market should never have existed. The Okubos should not have had to open the store in Denver to rebuild their lives. The decision that Lavelle and Scott made to preserve the memory of Ben’s Super Market at Ephemeral spotlights the inspiring legacy of the family’s resilience. But it is also an everyday reminder of the injustices that can be committed by a nation when we lose sight of the shared ideals that unite Americans of all backgrounds. It’s a heavy thought to grapple with over a beer, but we benefit from having places like Ephemeral that encourage us to do so.

Today, Derek Okubo is the head of Denver’s Agency for Human Rights and Community Partnerships, a unit of the municipal government that traces its history back to 1947, when Derek’s grandparents were restarting their lives in the city he now works to make more welcoming and equitable for all who call it home. Derek has led the agency since 2011, but he is looking ahead to what he will do when a new mayor takes office later this year. As he thought about it, he smiled and took a sip of his beer, saying “Maybe I’ll be a bartender.“ It might have been a tongue-in-cheek suggestion, but as we continued talking over our beers, I looked up at his grandfather’s sign and I could see the logic in it. Derek is a storyteller, a keeper of his family’s remarkable story. And establishments like Ephemeral are good places to tell stories that can have a lasting impact.