Story

Fighting the Invisible Empire

How Philip Van Cise took on the KKK and helped end the Klan’s reign of terror in Denver.

Elected as Denver’s district attorney in 1920, Philip Sidney Van Cise (1884-1969) used electronic surveillance and other cutting-edge investigative methods to expose a corrupt city administration and dismantle a crime ring that had been thriving in Denver for years. He then launched an undercover operation against an even greater threat: the Ku Klux Klan.

Originally a white supremacist terrorist group in the Deep South, the KKK was revived in Georgia in 1915 as a fraternal organization and spread across the country after World War I, attracting millions of followers by capitalizing on white Protestant fears about immigrants, Blacks, Jews, and Catholics. Under the leadership of physician John Galen Locke the Colorado Klan grew rapidly; after the 1923 election of Benjamin Stapleton as Denver’s mayor, with the secret backing of the Klan, the Colorado KKK became one of the most powerful state chapters in the nation, intent on moving past vigilantism to more sophisticated forms of economic and political warfare. One of the few elected officials to publicly oppose the group, Van Cise was targeted by them in a recall campaign that failed miserably. But he soon found himself in a series of escalating confrontations with the Klan—and in a desperate hunt for allies.

Editor's Note: The following is an excerpt from Alan’s book Gangbuster: One Man’s Battle Against Crime, Corruption, and the Klan, due to hit a bookshop near you in late March 2023.

Philip Van Cise pushed his war record in the 1920 race to become Denver’s district attorney.

They snatched Patrick Walker two blocks from his shop. A 25-year-old optician and active member of the Knights of Columbus, the Catholic fraternal organization, Walker had seen men loitering outside his eyewear store for the better part of a Saturday evening. They were gone when he locked up and walked south on Glenarm Place. But as he approached 21st Street, five men poured out of a car, guns drawn, and hustled him into the vehicle.

They drove north, past Riverside Cemetery, into sparsely populated farmland on the edge of the city. They took him into an isolated shack and asked him questions about his religion. Evidently not happy with the answers, they beat him with the butts of their revolvers, inflicting deep cuts and bruises on his head and shoulders, and told him to leave town. One of the men told Walker that they were KKK and were “looking for a man who had been doing some rotten stuff around town.” Before he lost consciousness, Walker managed to tell the men that he had done nothing wrong.

The police declared themselves baffled by Walker’s story. He could not identify any of his assailants, even though only one of them wore a mask. No identification, no arrest.

They snatched Ben Laska outside his house. The son of Russian Jewish immigrants and a former vaudeville artist, the 49-year-old defense attorney was known for performing magic in and out of the courtroom. Laska amused juries and annoyed judges with his sleight-of-hand routines, but his greatest trick was making the charges against his bootlegger clients disappear. One Friday evening, hours after Laska had gotten yet another rum-runner off with a small fine, he received a phone call at his home. A man who lived a block away on Cook Street was dying, the caller said, and needed a lawyer.

Laska agreed to a deathbed consultation. He was barely out the door when two men approached him. One grabbed him by the throat and slapped a hand over his mouth. The other seized his legs. They carried him to two other men waiting in a car. All four wore masks.

They drove north, past Riverside Cemetery. They dragged him out on a country road and beat him with blackjacks. They told him to stop defending bootleggers, or they would be back. Then they drove off.

Laska told reporters that he believed his attackers were Klansmen, in cahoots with “certain officers of the bootleg squad and officials of Magistrate Henry Bray’s court.” The assault on him was payback, he insisted, for being a zealous advocate for his clients.

Denver police chief Rugg Williams scoffed at Laska’s charges. So did Sergeant Fred Reed, head of the bootleg squad — and, like most of the squad, a Klansman on the sly. The actions of his men on the night in question were all accounted for, Reed insisted, and they were “too high-principled” to try to enforce the prohibition law with blackjacks.

The investigation went nowhere. Laska eventually made his own peace with the Klan, a feat as amazing as any of his magic tricks. By 1925 he had become the Grand Dragon’s personal attorney.

The beatings were anomalies. Grand Dragon Locke understood that the threat of violence was more palatable and often more effective than actual bloodshed. Get physical, and your foes may feel the need to respond in kind, while your more squeamish followers jump ship. But a well-placed threat, emanating from the unassailable depths of the Invisible Empire, could work wonders. It could instill fear in your enemies and inspire awe in your supporters at the same time.

The intimidation campaign was like the Empire itself, elusive yet ubiquitous. On the night of November 10, 1923, less than two weeks after the assault on Walker, eleven crosses were ignited at locations across the city. One was on the steps of the Capitol building; another, on the threshold of the Black neighborhood known as Five Points; others at parks and green spaces across the metro area. Alarmed city council members demanded an investigation. Mayor Stapleton and police officials downplayed the incident; they said they weren’t convinced there had been any crosses and didn’t see anything to investigate. A few weeks later, a string of crosses blazed in the foothills west of Denver, visible for miles.

Caravans of Kluxers drove through west Denver neighborhoods on Friday nights, hooting and honking, mocking Jewish residents and their Sabbath. Klansmen teamed up with hellfire Protestant ministers to host lectures on the Catholic menace. The Knights of Columbus were vilified as the advance guard in the Pope’s master plan to take over America; a fake Knights of Columbus oath, which bound the initiate to wage war on “all heretics, Protestants and Masons” to the point of annihilation, circulated widely among the credulous.

Possibly because they were more numerous, the harassment seemed to be directed at Catholics more than other groups. A savage KKK missive to the Denver Catholic Register declared that while Blacks, socialists, and Jews were bad enough, “the Romanist is worst of all.” The newspaper’s young editor, Father Matthew Smith, reported that cars swerved toward him more than once during his daily walks to his office, trying to scare him or injure him.

For the most part, though, the Klan’s bullying tended to be more subtle than trying to run down padres on the street. Under the rule of the new Imperial Wizard, Hiram Evans, the national KKK was moving away from street skirmishes to more politically potent measures. The new approach, which Locke heartily supported, emphasized “klannishness” — the concept that Klansmen must support each other in all endeavors. That meant voting for the “right” candidates, regardless of their party affiliation, and patronizing Klan businesses. It also meant shunning businesses that employed or catered to Blacks, Catholics, Jews, and other “wrong” types until they knuckled under or were driven out of business.

In Colorado, Klansmen were encouraged to advertise their businesses at KKK meetings, paying two dollars for the privilege of having a slide with a company logo projected on a screen for a few moments every week for three months. Members also let each other know their shops were Klan-approved by putting signs in the window that proclaimed they were “100% American” or TWK (Trade With Klansmen) — or simply by announcing that they offered “Kwik Kar Kare” or some other KKK-branded service. Extensive lists were drawn up of businesses to be boycotted, including the Neusteter’s department store, owned by Jews.

Many prominent businessmen embraced klannishness, including Gano Senter, owner of several restaurants downtown and a grand titan of the KKK. A virulent anti-Catholic, Senter posted signs in his Radio Café announcing, “We serve fish every day — except Friday,” and welcoming those in the know to a “Kool Kozy Kafé.” His wife, Lorena, was the founder and imperial commander of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan of Colorado, a ladies’ auxiliary devoted mainly to charity work. The Senters’ café quickly became a central gathering place for prominent Kluxers, who proudly smoked the special Cyana cigars promoted by Dale Deane, a Denver court clerk. Cyana was an acronym for “Catholics, you are not Americans.”

The boycotts typically hurt small businesses more than larger ones. Some were only tepidly supported and weren’t effective at all. Yet klannishness tended to boost membership. There may not have been many true believers, like Senter, passionate enough about their racism or religious paranoia to flaunt it publicly. But the inducements and pressures to join the Klan went far beyond ideological appeal. Some joined in the expectation that it would improve business, or at least keep them from showing up on a do-not-trade list. For every rabid nativist or rank opportunist, there were others who joined under duress, afraid of being left at a disadvantage or targeted themselves. Fear wasn’t just a weapon to train on the enemy. It was the glue that held the group together.

Van Cise was formally awarded a Distinguished Service Medal for his work as an intelligence officer in World War I in a 1922 ceremony, while his wife, Sara, and children Eleanor and Edwin looked on.

Van Cise kept count. Over the course of three years he was approached thirteen times about joining the Klan — cajoled, urged, pressed, told it was the smart thing to do. The final invitation came from the Grand Dragon himself, and then all hell broke loose.

That the Kluxers tried to enlist the district attorney, after failing to recall him, may say something about the cynicism of the movement. But it was also an acknowledgement that he was fundamentally different from the other outspoken foes of the organization, people like the NAACP’s George Gross and Father Smith and attorney Charles Ginsberg, who regularly spent his lunch hour denouncing the Klan from the bed of a pickup truck parked at 16th and Champa downtown, like a deranged prophet. Van Cise was a WASP, a Mason, and a Republican, and from a certain perspective his views on race and immigration could be considered Klan-friendly. That’s not to say that he believed in white supremacy; he took his oath to uphold the Constitution seriously. But he didn’t go out of his way to challenge the established order and prevailing prejudices of his time; even in coming to the defense of Ward Gash, a janitor the Klan had threatened, he reportedly referred to Gash — a Black man ten years his senior — as a “good boy.” In a speech to a Kiwanis gathering in Fort Collins, he lashed out at Governor William Sweet as a “millionaire Bolshevik” who had recklessly pardoned dangerous criminals, a law-and-order theme sounded by the Klan as well. He also declared that “southern Italians, southeastern Europeans and Turks made poor citizens.” His experiences in the Colorado National Guard during the 1914 coal strike had taught him respect for the immigrant miners he met, but he believed the country was having trouble assimilating so many foreigners from different cultures. “This is our country,” he told the Kiwanis, “and no one has a right to come here or live here unless we want him.”

At the same time, he was repelled by just about every aspect of the Klan. Its teachings were ridiculous, a hash of conspiracy theories, cornpone Christianity, and racial fears that only the dimmest of its members seemed to take seriously. The rank and file weren’t as gullible, but they were spineless enough to go along with it anyway, hoping to get something in return. The leadership consisted of thugs and con men, hiding under hoods and working a scam. The organization was ruining businesses, dividing people, and profiting off their misery. It was a menace to democracy. “It is injecting into the political and social life of this country a religious issue which has no place in either,” he wrote in a draft of a speech that he hoped to deliver someday to an audience much larger than the Kiwanis Club. “It may call itself Klan, but in reality it is a mob.”

He knew how to prosecute a criminal conspiracy involving bootlegging or confidence games. But in those cases, the primary goal had always been profit. The Klan’s objectives were much more complex — money, sure, but also power, and a purging of anyone and anything the group didn’t consider to be 100% American. How do you stamp out a conspiracy that eats away at the very institutions you count on to put things right? In its first year, the Stapleton administration had promoted klannishness in one city agency after another. The result wasn’t pretty. It resembled the work of an army of carpenter ants, burrowing its way inside the bole of a maple tree and hollowing it out, leaving behind a pile of sawdust and a stately husk, ready to collapse.

One of Stapleton’s first appointments was Rice Means, the manager of safety. An impressive orator who’d failed in several runs for office, Means denied being a Klansman. But Van Cise learned that he had been initiated into the Klan in a ceremony in Pueblo shortly after Stapleton’s election and was reportedly being groomed for higher things by Locke. Stapleton soon named him as city attorney, filling the manager of safety post with another Klansman, Reuben Hershey.

Over at the police department, Stapleton retained the services of the sitting chief, Rugg Williams, for several months, despite mounting pressure from Locke to replace him with someone of the Grand Dragon’s choosing. Williams was a placeholder at best; word was that key decisions about assignments and promotions were being made by subordinates, including a sergeant who boasted that he was the “real” chief. Whoever was in charge, the police seemed to investigate only those crimes that the Klan wanted investigated. The cross burnings remained a bit of unsolved mischief. After the Capitol Hill neighborhood was papered with Klan posters one night, including some hurled into a Knights of Columbus lodge, street fights erupted between the lodge members and Klansmen; police managed to arrest several of the Knights of Columbus brawlers, while the Klan provocateurs somehow slipped away.

Disturbing as the police takeover was, it was the spread of klannishness in the courts that most alarmed Van Cise — especially the ascension of the Honorable Clarence J. Morley. A former public administrator and school board member, Morley had been elected to a six-year term as a district court judge in 1918. He was a slight man, bespectacled and owlish, who came across more as a taciturn, humorless accountant than a dynamic jurist. Van Cise had dealt with him rarely. But in 1924 Morley was assigned full-time to the criminal division, and he and Van Cise were soon at war with each other.

Van Cise’s inquiries confirmed that Morley was Klan, and pretty high-level Klan at that. The district attorney had five operatives — a mix of volunteers and trained investigators, none of them known to each other — keeping tabs on Klan meetings. They hid in the bushes and wrote down license plates, tried to infiltrate the meetings when possible. Morley spoke regularly at those gatherings. He was a klokann, one of three top advisers to the Grand Dragon. Despite the title, Morley was usually on the receiving end of the advice; he seemed to relish being in Locke’s inner circle and doing his bidding.

It was customary to empanel a new grand jury in the criminal division at the start of the year. Morley took a klannish approach to the process. He rejected ten of the twelve names that had been randomly selected for jury duty and issued subpoenas, summoning a Klan-approved squad of replacements. Morley instructed them that they could seek the district attorney’s advice if they wanted to, but they could also banish him if they chose.

When Van Cise learned of Morley’s instruction, he was livid. Colorado law clearly stated that district attorneys “shall appear in their respective districts at any and all sessions of all grand juries,” and that it was their duty to advise the jury and examine witnesses. He went to the grand jury room to explain this to the panel. He had just started to talk when a juror interrupted him.

“We don’t need your advice, and you can get out,” he said.

Van Cise replied that if it was up to him, he’d be glad to part company with the bunch right now. But the law required his presence. The law expected him or his deputy to question witnesses, not them.

John Galen Locke, the eccentric Grand Dragon of the Colorado Realm of the Ku Klux Klan, was described by one reporter as “living in the Middle Ages.”

“What do you think about Sgt. Reed?” another juror demanded.

Reed, the head of the bootleg squad, had reportedly fallen out of favor with Locke and was being reassigned. Van Cise responded that he thought Reed was an able officer.

“We don’t think so,” the second juror snapped. “We’re going to indict him.”

In a flash, Van Cise saw what Morley was doing. He had assembled a private panel of inquisitors to unleash the powers of the grand jury against the Klan’s enemies, alien or internal. To hell with the rule of law, to hell with due process.

“Any such indictment,” he said, “will be attacked by the district attorney, and any action of this grand jury will be investigated.”

Before departing, he warned the group not to call any witnesses in his absence. For several weeks, he was too busy to bother with Morley’s grand jury, preparing for the biggest murder trial of his career. Joe Brindisi, an Italian immigrant and former streetcar conductor, was charged with killing Mrs. Lillian McGlone and Miss Emma Vascovie in McGlone’s Denver apartment last summer. Police theorized that McGlone pulled a pistol on Brindisi during a quarrel over romance or money or both, and that Brindisi pried the weapon from her and shot both women in the head. Fearing a lynch mob, Brindisi fled to Mexico, only to be arrested in Detroit months later. Anti-immigrant feeling was running high — the newspapers referred to Brandisi’s “swarthy” good looks and dubbed him the “sleek sheik of north Denver’s Little Italy” — but Van Cise was determined to get a conviction based on evidence, not hysteria.

The courtroom was packed. Extra guards roamed the halls and kept close watch on the gallery and the defendant. Judge Morley presided. During one of the recesses Morley summoned Van Cise to his chambers and showed him a note from the grand jury. The group had been meeting without Van Cise’s knowledge and, since the DA was busy with a murder trial, requested that a special prosecutor be appointed. Morley had a certain Klan lawyer in mind for the job.

“Morley demanded that this be done and cursed me when I refused to accede to this request,” Van Cise wrote in an account of the conversation. “Morley told me that he was doing this to protect me, and I told him that I needed no protection from him or from anyone else, and that he or anyone else, if they desired to make charges against me, could go into open court and do it, and for them to cut out all this secret and childish stuff.”

Van Cise’s closing argument in the Brindisi case was a memorable one. He arranged the blood-stained clothes of the two women to show the positions in which their bodies were found and walked the jury through a step-by-step re-enactment of their murders. It was “a seemingly perfect chain of circumstantial evidence — with every link well formed,” one reporter observed. The jury was out thirteen hours, quibbling about whether it was first-degree or second-degree murder. They decided on first-degree. Since the prosecution had not sought the death penalty, that meant life in prison for Brindisi.

The accolades for the district attorney poured in. The most unusual plaudit came by Western Union to his home. “Congratulations on your splendid address to the jury and your wonderful victory,” the telegram read. “Dr. J.G. Locke.”

He had never received such a nice note from someone he hoped to put behind bars.

Two days later, Dr. Locke presented himself at the district attorney’s office. He wore a well-cut suit, not the robes he favored for more festive occasions. He once again praised Van Cise for his handling of the Brindisi case. Then he urged the prosecutor to consider running for governor in the fall — with, of course, the backing of a certain group, a group so well-known that there was no need to mention its name. “You know that we have a very strong and influential organization,” he said. “And we want to back a man of your type and caliber.”

Van Cise declined.

The next day, Mayor Stapleton named a new chief of police, William Candlish. A former state senator and assayer, Candlish had no background in law enforcement and a pile of debts from a failed radium processing venture. Stapleton and Manager of Safety Hershey had differing accounts of how Candlish happened to be selected, but it soon became obvious that he was Locke’s man. Candlish got busy with promotions and reassignments, rewarding Klan members on the force with plum positions and banishing Irish Catholic cops to remote beats and night shifts. He devised a chief’s uniform that was heavy on gold braid. Noting that the chief seemed to spend a lot of time in soda parlors, which often served as fronts for bootlegging operations, Ray Humphreys of the Denver Post dubbed him Coca-Cola Candlish.

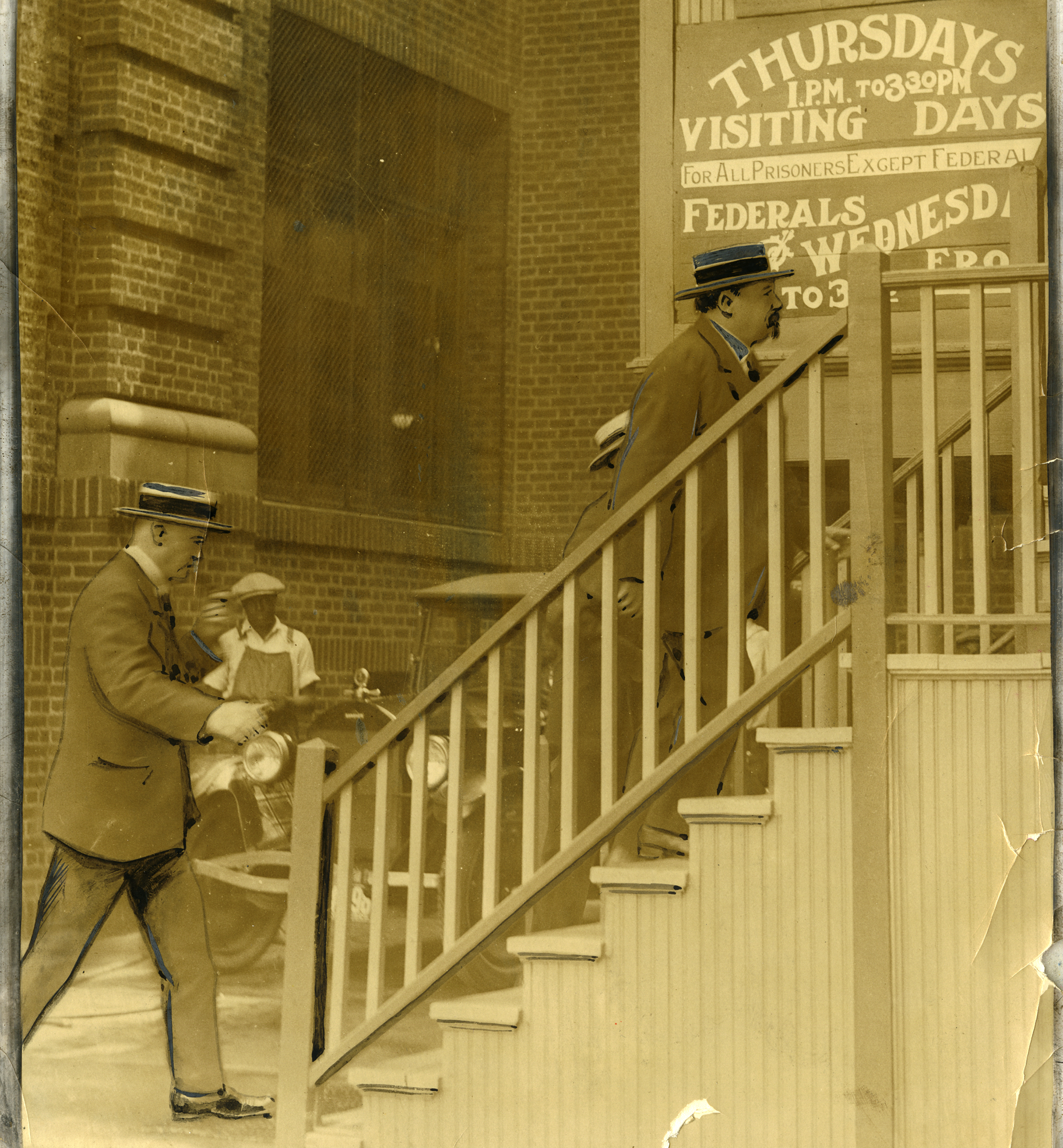

June 13, 1925: Accompanied by attorney Ben Laska, Locke reports to the Denver jail to start serving a sentence for contempt in a federal tax case.

For former Stapleton supporters who’d cheered his promises to reform the police department, the Candlish appointment represented one more betrayal. It gave impetus and urgency to a campaign to recall the mayor, launched by attorney Phil Hornbein. The petition didn’t mention the Klan influence directly, but among the grounds for the mayor’s removal it stated that the police force had become so demoralized that “crime runs rampant in our midst.”

Van Cise recognized that the recall process might be the best chance of stopping the Klan in its takeover of city government. A successful criminal prosecution of the group was unlikely — not in Morley’s courtroom, surely, and not on Candlish’s watch. He had to find a way to take the intel he’d gathered on the Klan leadership and deliver it, all neatly tied in a bow, to a higher court: the citizens of Denver.

A public official looking to spill secrets in Denver had many niche publications to choose from, including a Black weekly, a Jewish weekly, and a Catholic weekly. But of the four major dailies in town, only one had shown any appetite for going after the Klan. The Rocky Mountain News and the Denver Times, both owned by the same company, had Kluxers in management and were largely mute about the organization. The Denver Post blew hot and cold; at Klan meetings, Locke bragged of having taken one of the paper’s owners, Harry Tammen, for a ride one night and “made him a Christian.” Another insider account had it that Locke had ordered Tammen’s partner, Frederick Bonfils, to retract an unflattering story and run another one praising the Klan — or else his newspaper building would become “the flattest place on Champa Street.”

With the other newspapers so compromised, that left the runt of the litter, the Denver Express. Owned by the Scripps-Howard chain, the paper had a puny circulation and no showcase Sunday edition. It lured working-class readers with celebrity gossip, puzzles and contests. But led by editor Sidney B. Whipple — a short, skinny Dartmouth grad in his mid-thirties, who’d been a foreign correspondent in prewar London and found journalism too exciting a vice to give up — the Express did more investigative reporting on the Klan than anybody else. Initially an earnest supporter of Stapleton, Whipple had spent considerable time and ink repenting his decision and tracing the mayor’s unsavory connections.

On March 27, 1924, the Express dropped a bomb on City Hall — the first installment of a week-long series entitled “Invisible Government.” The exposé peeked under the sheets and named names. Outed as Kluxers: Mayor Stapleton. Manager of Safety Hershey. City Attorney Means. Chief Candlish. Judge Morley. Police magistrates Albert Orahood and Henry Bray. Carl Milliken, Colorado’s Secretary of State. “At least” seven police sergeants and twenty-one patrol officers. And “nearly all, if not all, of the present county grand jury now in session.”

The report didn’t identify its sources, but Van Cise’s fingerprints were all over the piece. Among other giveaways, the article mentioned that Dr. Locke was planning to put a Klansman in the governor’s office, and that the district attorney had been approached about the job and turned Locke down flat. By nightfall the series was the talk of the town — and an emerging crisis for the Klan. If this was the opening salvo, what was in store for the next seven days?

That evening Locke’s office had a steady stream of visitors — mostly men huddled in overcoats with their hats pulled low. At ten o’clock an Express reporter confronted Judge Morley as he emerged from the building. Why was a district judge paying a call on the Grand Dragon at such a late hour? Morley said that he’d been feeling ill and decided to consult his physician.

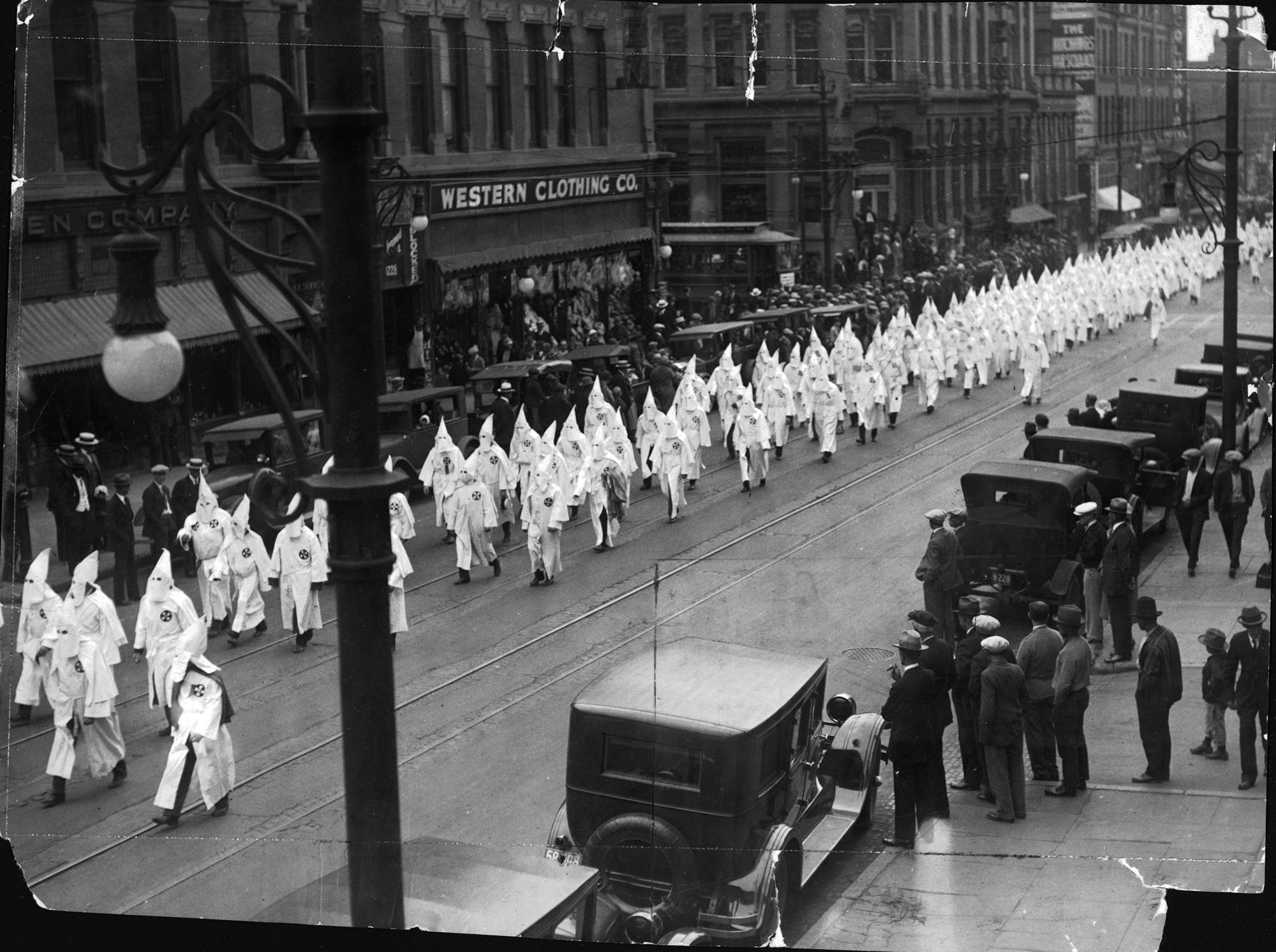

Klan members staged a Memorial Day parade in downtown Denver on May 31, 1926. Tens of thousands were expected to attend; less than 500 showed up.

The next morning two men barged into the Express office and demanded to see the editor. They showed Whipple an arrest warrant and told him he was summoned to appear before the grand jury. The panel had been dormant for weeks, but the Express series had brought it back to life, for the sole purpose of investigating how Whipple had obtained the information he was publishing. Before they took him away, Whipple told an assistant to call Van Cise and let him know he was being arrested.

Van Cise was waiting at the courthouse when Whipple and his escort arrived. He followed them as they went upstairs to the grand jury room and went inside. Two Klansmen stationed by the door tried to bar the district attorney from entering. He pushed past them and went in. He was succinct. The grand jury, he informed the panel, has no power to arrest anyone. Whipple could sue them all for damages. They couldn’t question him unless Van Cise was present. And he was putting an end to this “travesty” right now.

He grabbed the diminutive editor by the arm and walked out. No one followed them.

That was on Friday morning. Over the weekend Morley held more secret sessions with the grand jury while the Express series continued to stir the pot. KU KLUX KLAN BOASTS RULE OVER CITY HALL, read one headline. CHIEF CANDLISH GIVES KLUXERS INSIDE JOBS, read another.

On Monday Morley directed the district attorney to appear in his courtroom, in the presence of the grand jury, so that he could hear the judge’s instructions to the panel and cease his interference. Van Cise came prepared with a motion of his own, asking the judge to correct his instructions and tell the grand jury that the DA must be present at all sessions, other than the jury’s actual deliberations. As Van Cise read his motion aloud, delineating the judge’s illegal acts, Morley’s face reddened with rage.

“There is nothing in that motion,” he said. “It’s simply a cheap play for notoriety on your part.”

Morley embarked on a long tirade. That was fortunate, as Van Cise was stalling for time. Just as the judge seemed to be winding down, deputy DA Kenneth Robinson arrived with a bundle of writs — one for each juror and one for the judge. Van Cise stood up.

“Notwithstanding what this court has now said,” he began, “and notwithstanding the additional erroneous instructions to this hand-picked, so-called grand jury, I now have the pleasure of serving both the court and all the jurors with writs of mandamus from the Supreme Court of Colorado, ordering you to hold no further sessions of this jury without the presence of the district attorney.”

The writs were handed out in dead silence. Morley read his copy and turned to his grand jury. “Gentleman of the jury, you are excused for one week,” he said. “The court will be in recess.”

Morley’s attempt to challenge the order was argued in the Supreme Court at the end of the week. The law was on Van Cise’s side, the decision unanimous in his favor. By that point the grand jury’s term had expired, with no indictments issued against anyone.

In the wake of the Express series, eleven of the newspaper’s largest advertisers were told to stop doing business with the paper or face a Klan boycott. Several complied, costing the newspaper substantial revenue. But Whipple kept sticking his nose in the Klan’s business and pushing for the mayor’s recall, drawing heavily on information provided by a well-informed anonymous source. His dogged coverage made him and his small paper finalists in the reporting category for the 1925 Pulitzer Prize.

Van Cise savored his victory over Morley’s grand jury. It showed that the Klan could be beaten; its influence had not yet reached the highest court in the state. But the most important battles were still ahead, the mayoral recall and the statewide elections in November — battles that would be fought in the streets and the voting booth, not in court.

As it turned out, the Invisible Empire had the numbers and the strategy to prevail. Stapleton easily fended off the recall, Rice Means became a U.S. Senator, and Clarence Morley became the governor of Colorado. But that stunning wave of victories was only the prelude to an even more astonishing series of political defeats. Just months after the election, the Colorado Klan’s leadership would be mired in scandal and internecine warfare. In his last days in office, Van Cise would make a crucial contribution to the group’s rapid collapse, filing felony charges against Grand Dragon Locke and laying the groundwork for other damaging revelations to come.

From GANGBUSTER by Alan Prendergast, reprinted with permission from Kensington Books. Copyright 2023.