Story

Come Ride With Me

A bikepacker’s backward glance at the history of Colorado’s cycling scene.

It was the summer of 2021. I was cycling with my supplies stuffed into a waterproof wet-bag strapped onto my bike rack along the steep ridgeline of the Blue Mesa Reservoir near Gunnison, Colorado. Cars swooped by me so fast that their tailwinds pushed me into the roots of the aspens lining the highway. Alone, and on day three of a bikepacking trip from Denver to Delta, I was taking a break at one of the viewpoints when a retired couple from Texas chatted me up. They asked where I cycled from and where I was going. After I explained my route the woman gasped and offered to hitch me to the next town. I was feeling the struggle, and by this time in my life I’d learned to trust help and to be okay with hitchhiking. I took them up on their offer, and as the couple drove me twenty miles closer to my final destination, the man looked back at me through his rearview mirror “You do this alone?”

I met his gaze in the mirror, “Most of the time yeah, I’ve had good luck with people, most just want to help.” I got the impression that he asked because I was a solo female cyclist riding through some of Colorado’s most remote terrain. But maybe that was a big leap in thought? Either way, they dropped me off at the next town and shaved two hours off my total time on the bike that day. I was able to pull up to my final destination in time for celebratory Jell-O shots with my awesome Deltoid friends.

Fast-forward to the summer of 2022. I was swapping ideas with my work cohort at History Colorado and looking back fondly at that biking adventure. I boasted I had just completed a 130 mile round trip bike ride from Denver to Colorado Springs the previous Sunday, and was promptly offered an assignment: write about bikes and relate it to history. While I inadvertently oozed confidence in my cycling capabilities, it turned out this assignment was not low hanging fruit for me. The first couple of full length drafts were scrapped. The assignment morphed from nostalgic weaves of feminism, the mechanical history of cycling, to trash alley cycling grunge. So I started over. Then I started over again. Turns out I have lived bike experiences that should not be put into print, and apparently needed my editor to look me in the eye and tell me that. But by the time I finished this article, I was officially dubbed the bike expert. This is my bike story. The ride you’re about to join me on is intended to give you chuckles and hopefully lend a different perspective on bike history and cycling in Colorado.

A Transportation Revolution

I took for granted, while living in the bicycle mecca of Colorado, that historically speaking, bikes weren’t always a common display of aerodynamic finesse. How did bikes become such a part of the urban landscape that they almost blend into peripheral vision for city dwellers like me? Before writing this article, my bike knowledge of weight and frame styles was limited to fairly modern examples. I had little contextual understanding of historic bike frames. I think the tall-wheeled penny farthing frame is probably what came to mind when I’d imagine “older” or “vintage” bikes. Come to find out, my own vintage bikes have a slightly more evolved frame style than those turn of the twentieth century models of my imagination.

I have a twenty-pound, 2001 steel framed, nine speed Talladega Bianchi. Her name is The Princess Bianchi, (yes, each of my bikes has a name). Another of my bikes—a steel-framed fixed gear beauty weighing in at twenty pounds—was my first adult bike. She was my teeth cutter (but her name is unprintable). Later in an act of personal defiance I purchased a carbon-framed Trek Checkpoint (Rodney) which I built and Frankensteined together myself. He weighs 16 pounds. It’s okay if you haven’t named your bike yet, there’s still time.

According to Margaret Goruff’s book, The Mechanical Horse, we must rewind back to the seventeenth century famine in Europe to trace bicycle history to its roots. The famine caused a widespread slaughter of horses and prompted the creativity that trying times often do. Horses, at the time, were the standard method of distance travel. In the midst of the horse-meat wholesale slaughter, German inventor Baron Karl Drais, created the bicycle prototype in an effort to replace the horse. It was known as the draisine, its wooden frame was the predecessor to the bicycle. Slowly, advancements were made to include iron parts, better wheels, and later a steel frame.

Early bicycles in the nineteenth century, although increasing in popularity, were still by no means mainstream. Even with their advancements from the early wooden draisine, they were heavy, cumbersome, and lacked technical functions. In the United States, the earliest bike frames positioned riders upright instead of the aerodynamic forward tilt more commonly seen today. Derailleurs, which are the mechanisms on bicycles that switch the chain on sprockets of different sizes, were first used by European cyclists in the early twentieth century. Upright and lacking a way to shift gears, American bikes back then couldn't adjust to hills or long flat roads.

The twentieth century postwar economic boom changed the range of capabilities bikes could offer Americans due to increased global trade. The British economy struggled after World War II. In response, the United States cut tariffs on British bicycles in half, which helped put affordable lightweight bicycles into the hands of many more Americans, and helped boost the British economy. Two birds, one stone. British imported bicycles came with those fancy European derailleurs and thus opened the range of possibilities of tackling varying topographical terrain for cyclists. The US market responded to the demand by adding gears—initially three seemed like more than enough—to American-made bikes.

By the 1960s, American bike producers were manufacturing eight- and ten-speed models that were more affordable than their imported European counterparts. They were heavy, but offered more diverse land coverage than the clunky single speed cruisers of the era. To help put the evolution of bikes into perspective for modern cyclists like myself who are accustomed to sixteen pound bicycles, the Schwinn Varsity, weighing in at forty pounds, was considered lightweight in the 1960s. Perhaps this is why bicycles from the early twentieth century are either in museums, or decaying in scrap yards, or are collecting dust in garages or personal cabinets of curiosities. I have yet to see one on the road. I digress, but the point here is that bicycles have come so far in terms of frame aspects, weight, and materials for the sake of improving the feel of the ride itself.

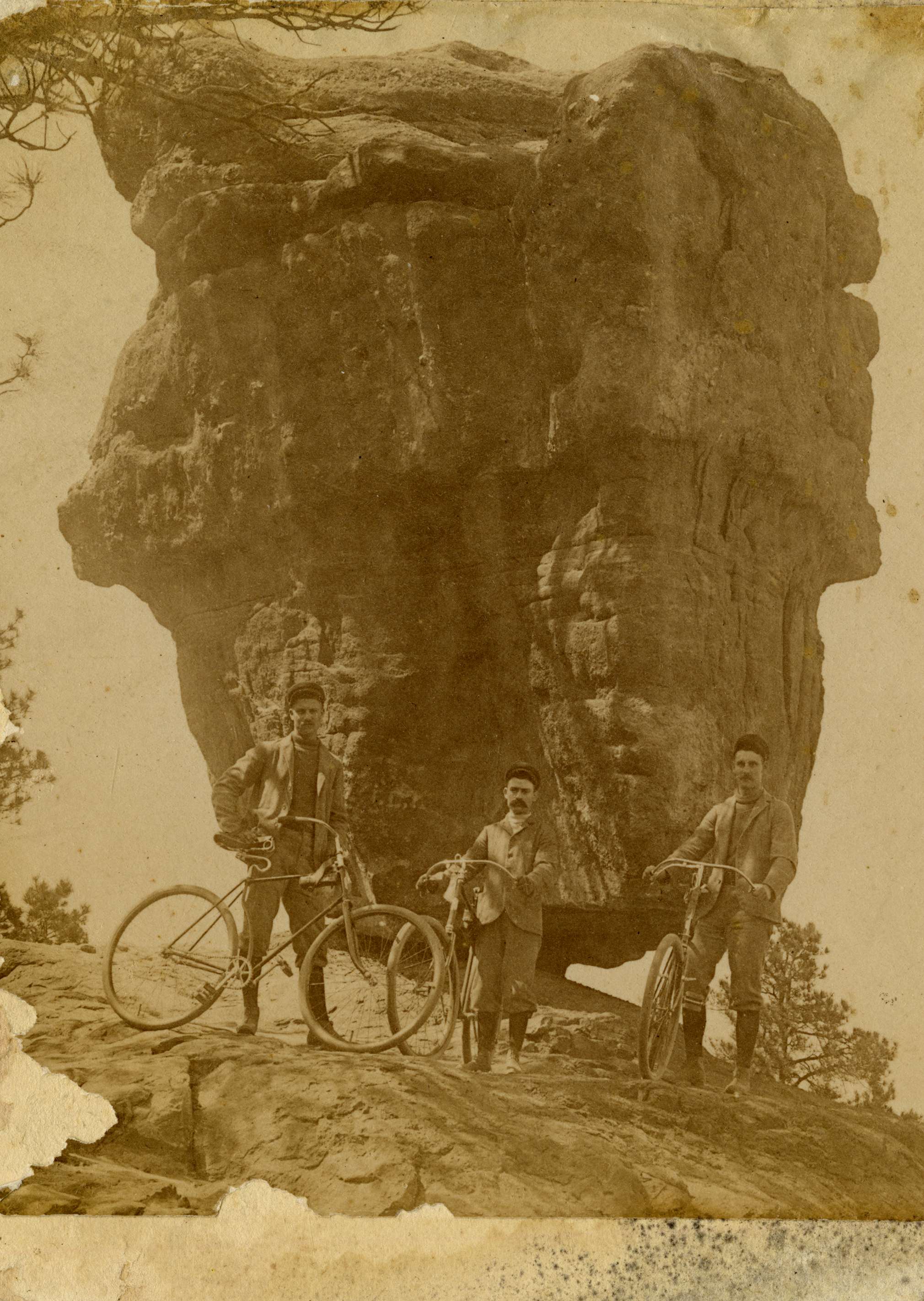

Cyclists stare down the camera at one of Colorado’s top natural wonders, Garden of the Gods.

A Social Life on Two Wheels

Cycling was historically, and continues to be, a social activity. As much as I pride myself on cycling solo most of the time, in reality, I came back to biking in my adult years so I could ride with friends who loved the sport and wanted to hear my famous one-liners on the road (I’m just kidding, they actually have no choice but to hear my jokes). I may be cheesy, but I’ll make you laugh as we crank up a hill together!

Nevertheless, there’s still cultural mysticism surrounding the lone cyclist. Epic solo rides have made the news for nearly a hundred years: A young Canadian man, Stanley Mathias, made Denver Post headlines in 1928 when he cycled through Colorado from Canada—an epic 7,000 mile journey. Averaging between ninety and 100 miles a day, the Royal Gorge, Canon City, Skyline drive, and Garden of the Gods were just a handful of his Colorado stops. Mathias was quoted in the Post, assuring his readers that “Traveling by bicycle is very economical.”

His journey drew the press to him at the time, but his assurances of affordability caught my eye. Mathias told reporters that he spent $150 for his two-and-a-half-month journey in 1928, which amounts to about $2600 when adjusted for inflation today. Somehow, I spent nearly $1000 on a week-long ride from Denver to Salt Lake City. Relative to my bikepacking journey (which certainly had some unexpected turns), less than $3,000 seems affordable for two months on the road. While not cheap in aggregate, breaking costs down day by day keeps cycling a cost-effective alternative to the daily grind. This is true especially in comparison to a week’s vacation on a beach or campground. Designer bikes don’t need to be the entry point. A bike with gears, good tires, and a fairly comfortable fit will travel long distances and get you where you want to go. After all, protecting one’s wallet from bruising is certainly part of making it a comfortable ride.

Mathias was a solo cross continental bike traveler, a fairly new style of adventure in the early twentieth century. Over the course of the 1900s, bikepacking became mainstream in the United States. The famous European Tour De France already existed, having started in 1903, but the United States was still catching on to tour cycling.

But by the 1970s, the craze had taken hold. In Jody Rosen’s book, Two Wheels Good, he notes that for three straight years: 1972, 1973, and 1974 bicycles outsold cars. In 1976, to commemorate the nation's bicentennial, thousands of those new bicycle buyers came together for an epic journey known as the BikeCentennial. The ride, which drew cyclists of all abilities, traversed the United States from Oregon to Virginia.

There were two kinds of tickets available for that early BikeCentennial tour: in-camping and out-camping. It was $8 a day for the outdoor version and just $4 more for the indoor version (which wasn’t luxurious by any means). The indoor cyclists slept in libraries, dorm rooms, churches, and the like while their outcamping counterparts slept in farm fields or parking lots. Keeping in mind the overall expense of the trip for eighty-two days, cyclists would either pay $656 or $984 respectively, or about $3,432 and $5,148 today.

Reading Rosen’s chapter on monumental cross country rides like the BikeCentennial woke up parts of my brain that recall more socially oriented bike experiences which I had suppressed after being caught up in Colorado's Triple Bypass COVID-19 kerfuffle in 2020. I felt justified in my wariness of group rides after losing out on the ride and my registration fee. (Yes, next time I will get rider insurance!)

The Triple Bypass was the first supported event I had ever signed up to ride. I loved the idea of cycling crews feeding me bagels, peanut butter, and Bobo bars while I cycled around with a bunch of like-minded bike enthusiasts. And it was a trusted event, dating back to 1988 when a small cycling cohort thought it might be fun to try a wild climb up three mountain passes—Juniper Pass (11,049 feet), Loveland Pass (11,991 feet), and Vail Pass (10,666 feet)--in a single day. The summer of 2023 marks its thirty-fifth anniversary. Thousands of cyclists sign up every year. And it’s just one of the cycling events in Colorado each summer that draw cyclists in from all parts of the globe.

Hindsight being 20-20 (pun intended), in the summer of 2020 I should have guessed that the close proximity of cycling in large groups made the Triple Bypass ride impossible to keep open to the public. I remember sitting in the Best Buy parking lot in Lakewood when I got the email that the event was canceled. The cancellation left me wary of big box cycling events, despite their often philanthropic goals. Instead, driven outdoors by the pandemic, I rode my own routes unsupported and alone. But solitude can be wonderful. Bikes, not COVID, taught me that.

That summer, rather than bagging the three peaks of the Triple Bypass, I committed to riding to the summit of Mt. Evans solo. But instead of driving to Idaho Springs and riding up Mt. Evans from there following the route of the annual Bob Cook Mt. Evans Climb, I rode from my front door in Lakewood to the top of the 14,200 foot peak and then back home. At the time it was very important to me that I separated myself from the event cyclists who shuttled down the mountain afterwards for free beer and pizza. Anyone who has ridden Mt. Evans knows the worst part isn’t the climb, it’s the descent down the treacherous, altitude-worn road that event cyclists avoid by simply shuttling down in a bus. But even that ride wasn’t enough. Still looking for escapes during the pandemic, I bike-packed from Denver to Delta, from Denver to Paonia, and from Denver to Salt Lake City, each its own separate journey. Instead of the support of a cycling crew, I chose to support local businesses along my routes. (By the way, Brother’s Deli in Idaho Springs is a Colorado treasure that serves up delicious sandwiches to fuel a climb through the high country).

I didn’t start cycling till I was thirty. And I wasn’t a professional athlete in my twenties either. People I’d seen on the road only strengthened this sentiment. I met a man riding across the dry canyonlands of Maybell on a recumbent bicycle to crowd source funding for his own cancer treatment. He accessed different channels of fundraising for his own health, using his bike to spread the word. I point this anecdote out to my able bodied friends wary of rigorous distance travel. Naturally there will be individuals who can’t physically ride a bicycle, but for many there is a way.

Bikes have lived somewhere between toy and transportation for over 100 years.

Writing this article prompted me to research the history of bikepacking and bike touring in the United States, and it reminded me of the urge to go out with friends, supported by the energy of hundreds of other riders and complete an epic ride with goals. Maybe this summer I’ll consider shelling out three hundred clams to grind up some hills and get my free Bobo bars at the end.

From Transportation to Toy

I’m not anti-social even though I often ride alone. I did try to create my own personalized cycling buddy in the form of my now ten-year-old son. I envision grand bikepacking trips with him as he grows into adulthood, but we need to start with a simple overnight bikepacking trip to Bear Creek State Park before I can prime him for a multi-day trip. But I couldn’t help myself: I started planting the bikepacking seed three years ago.

In the spring of 2020, with public school shut-downs and while remote working, I set out to finally teach my son to ride the bike I got him for Christmas. It was permanently parked in his closet, but I had hoped that he would catch the cycling bug so we could ride together. Bikes began as an alternative mode of transportation for adults lacking a horse. But at the turn of the twentieth century, just before World War I, bicycle manufacturers began looking to young boys as their new target audience. Automobiles were taking their fathers out of bike saddles and placed them behind the wheels of gas powered machines. It became a symbol of growth into adulthood for children to embark on independent bicycle riding and develop fortitude and strength in the ways that bicycles do. Government officials thought that good cyclists would make healthy soldiers. While I don’t feel like the goal of cycling should be to prime my child for military service, I do agree that it establishes healthy independence and increases fine motor skills—abilities that take time to cultivate in awkward young bodies before the finesse of adult physical mobility takes hold.

The youngest cyclist to complete the BikeCentennial trail in 1976 was nine years old. I didn’t know children could bike across the country as young as nine years old—but when the pandemic quarantine arrived, I knew seven was the perfect age for my own child to start training. I carefully set up time in between his remote classes during the day to introduce the sport to him. It was a lonely time, but we made the very best of it. I wanted him to use his bike for enjoyment. For fun. Three years later, while I still have some grandiose plans to ride across the country with him in celebration of a national holiday, I would settle for an overnight bikepacking trip.

In trying to create my adventure buddy early on, I set out with the kiddo on three separate bike training sessions in the spring of 2020. I remember assuring my still-learning son that he didn’t have to take off on his own, he just had to get used to sitting in the saddle and holding the handle bars even if his feet were planted on the ground. Witheach attempt, his body learned something new. I reminded him that he was getting used to being on a bike. He didn’t have to be perfect right away. Finally after several attempts, on a sunny day in April, I took my son to a little gravel loop park that encircles a goat grazing patch in Wheat Ridge. I kept running next to him and holding the bike while he pedaled and I could tell that he felt himself handling the bike. I was grateful that bikes were no longer made from forty pounds of steel. I don't think I could have pushed him along if his bike tipped the scales like its predecessors.

I panted as I ran along next to him, lap after lap on the gravel loop, holding his handlebars and steering him so he could feel flight. He finally said to me matter-of-factly, “you can let go now, mom.” Although he was probably only talking about his bike, I felt an entire lifecycle of parenting wash over me when I took my hand off the saddle. He took off and pedaled freely around the loop. Witnessing his first experience of personal freedom and his pride brought me straight to a bout of ugly crying. He didn’t hear my weepy, smotherly, chortle of happy tears: He was too busy yelling and experiencing physical mobility and speed unlike anything he had likely felt before. The following summer he did his first twenty miles and let me know in his funny string of consciousness “I’m cooking like chicken mom!'' The boy can ride and my hope is that I don’t over-impose my hobby onto him so he will join me in bike ride bliss. He named his first bike “The Cherry Fixie.” Bikes aren’t just for kids, but I’m not sure if any demographic of cyclist appreciates it the way a child does—especially that first time they take flight.

Smiles for miles on this vintage “steed” at Colorado’s Ride the Rockies event in 1991.

Cycling into the Future

In Colorado, cycling is often praised as an ideal mode of green transportation. But it’s still an afterthought to most people with access to a car, just like it was in the early twentieth century. However, broader sales trends indicate that certain bikes are as popular today as they were when they outsold cars in the 1970s. E-bike sales outstripped E-vehicles in the United States in 2021, so perhaps history doesn’t fully repeat itself but it does rhyme. The historical trend indicates that our two-wheeled machines are keeping up with the times. I know first-hand why Colorado is one of the top sports-cycling spots in the country. Our state’s epic mountains and famous group rides like the Triple Bypass or Ride the Rockies help confirm that impression. Unsurprisingly, the city of Denver recently ranked in the top ten friendliest bike cities from data sourced from the U.S census bureau, the U.S. Department of Transportation, the U.S. National Centers for Environmental Information, Walk Score, Rails-to-Trails Conservancy, Vision Zero Network, Google Trends, and Yelp. What a mouthful of data.

Writing this article broadened my thinking of what bikes are. They’re machines, certainly, but something else exists inside the frame. It’s almost like a wavelength carried through from the manufacturer, the excitement from the mechanic who opened the bike box, or the finesse of the last person who polished the frame. Bikes have a soul. People have adapted their bikes to suit different ideas of what bikes should be and do. They were originally intended to solve a transportation issue, but over time, they became a way to be together or, in the case of long solo tours, to recharge in solitude. For many,they proved to be integral to the early childhood experience of geographical autonomy. Most will learn to cycle before they learn to drive. Bicycles soften our footprint on the planet, make us look goofy, but also sometimes cool. Bikes simply won’t be defined by one subculture, one demographic, one frame style, or the many personalities who hop onto the saddle. Bikes are the tool of the user. Beholden to their people. But they still seem to have minds of their own.

From people craving either the solitude or the social connectivity of cycling, to retirees looking to get around town with ease, to adaptive mountain bikers searching for adventure, to those who just want to feel the breeze and see the sights, there is a bike waiting for you to take it home and give it a name. It’s not—it’s never—too late.