Story

The Lost and Found History of Central City

When the Works Progress Administration documented the life and history of the inhabitants of Central City, Colorado, they left out the important contributions of the working class, women, and immigrants. History Colorado’s collection has the key to these forgotten histories.

Each object in History Colorado’s collection has a unique and powerful story just waiting to be discovered. Supported by a grant from the Colorado Historical Records Advisory Board, I have used the collection to understand the untold history of Central City, Colorado. I worked with History Colorado to digitize the Works Progress Administration’s (WPA) Federal Writers’ Program Ledgers, created as part of a government program from the late 1930s and 1940s that sent writers across the country to document life in America. Writers came to Colorado to record natural features, flora and fauna, architecture, culture, agriculture, and industry in various regions of the state. These writers created eleven ledgers, titled City Guides, to describe their impressions of the most important stories and legacies of each city, often focusing on buildings and landmarks. Using the WPA Federal Writers’ Program ledgers, we can identify what parts of Colorado’s history were important to other Coloradans and the country in the 1930s, as well as the developments believed important in each town.

One Colorado town stood out to me during this project: Central City. Nicknamed the “richest square mile on Earth” and the “Little Kingdom of Gilpin” for its prominence in the Pikes Peak Gold Rush, Central City has a rich industrial and cultural history. However, while reviewing this town’s ledger, I found the WPA left out some important stories of Central City’s working class, immigrants, and women, which inspired me to dig deeper into History Colorado’s collection to try and fill in the gaps.

From Gold Rush to Gambling Hub

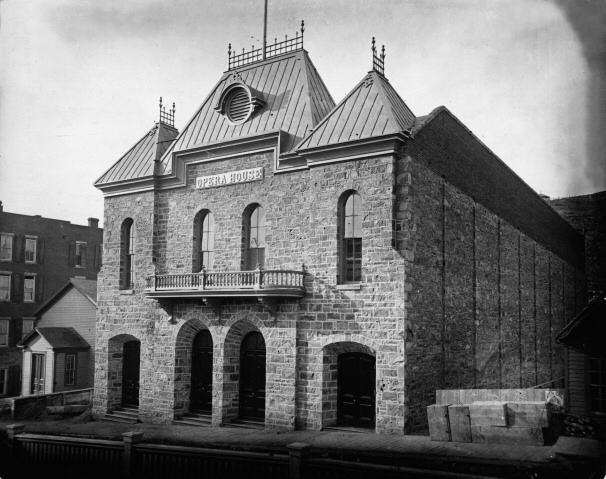

Gold miners founded Central City during the 1859 Pikes Peak Gold Rush. Growth was slow at the beginning and received little help from the federal government, which was focused on fighting the Civil War. But by 1870, the town was fully established and thriving, soon becoming perhaps the most important economic hub in Colorado and holding considerable political influence. But Central City was known for more than just its booming gold and silver mines—it was also a significant cultural center, and the construction of the Central City Opera House in 1878 solidified its cultural prestige.

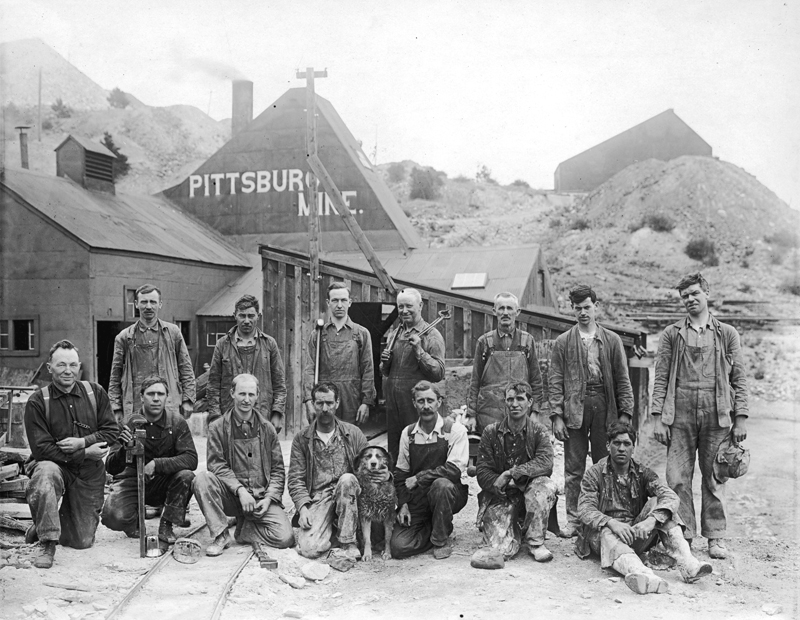

Miners in front of the Pittsburg Mine in Central City, circa 1900-1910.

The state’s economy diversified after statehood came in 1876. Once Denver became the state capitol, it eclipsed Colorado’s other towns. But Central City retained its importance, and in fact it experienced its height of wealth and population in 1900, just before World War I forced a dramatic decrease in productivity. Mines began closing down in the 1920s, and while there was a small return to the industry during the Great Depression, the beginning of World War II ended the mining industry for good in Central City. To aid the war effort, the government ordered all non-essential industries be shut down, including gold mining.

Despite mining’s decline, the 1930s saw a return of Central City’s cultural prominence. The Central City Opera House Association renovated and reopened the Opera House in 1932 and performances resumed. Tourists were the new gold rush, and they flocked to the town to see the renowned Opera House and neighboring Teller House hostel and hotel that had recently been converted into a restaurant and bar. Tourism supported restaurant, hotel, and transportation jobs, setting a trend that continues today.

Today, about 785 people call Central City home, and many of its residents work in the gaming industry that was made possible by a 1990 change to Colorado’s constitution. Legalized gambling revamped Central City and flourished in Black Hawk, a glittering resort town where towering casinos compete with the rugged cliffs for attention from thousands of visitors every year.

The WPA In Central City

The Works Progress Administration’s Federal Writers’ Program came to Central City to document the history and daily life of the town during its return to glory in 1936. Central City was experiencing a cultural revival, and that context shaped what the WPA visitors recorded. Because the Teller House and Opera House had been renovated and were currently in use, the authors found those to be two of the most important buildings in the town, though they also looked at other cultural institutions such as churches, schools, and social clubs. In general, the records focused on high society and their associated landscapes leaving little space to celebrate, or even recognize the working class.

Gold had propelled Central City’s rise, and consequently, the WPA writers saw the gold rush as a lens through which they could explain the origins of the town’s prominent families. But looking back nearly a century later, it can perhaps be more clearly seen that the town of Central City was built on saloons and gambling halls designed to entertain the miners and the working class. The authors mention these key aspects of the town's life and history, but do not make them a focus. Mining had a small revival during the Depression so it is likely there were a few active mines while the authors were writing the ledger. After reading through the Central City Guide I wanted to know why mining and the stories of the working class are not more prominent in the ledger?

The WPA Writer’s lack of diverse stories in the ledgers speaks to the power the wealthy held over the narratives of Central City’s history. The wealth of the mining industry created great cultural buildings like the Teller House, the Opera House, and the numerous churches and schools. While the industry came and went, these buildings remained constant. The rich and powerful were able to preserve the landscape that mattered to them while the working class moved on to find work elsewhere. This trend continued throughout the 1930s and into the 1940s when historic preservation efforts in Central City once again focused on these cultural symbols and less on the industrial ones. During their visit to Central City, WPA writers only saw these dominant narratives of wealth and high culture, and unintentionally removed the working class, immigrants, and women from the histories.

Untold Stories

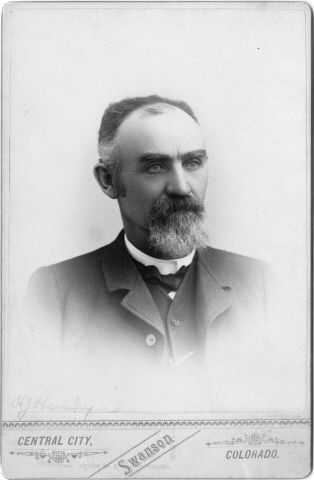

Deep in History Colorado’s archives, I found a journal belonging to a 21-year-old miner, Henry J. Hawley, detailing his travels across the plains from Argyle, Wisconsin to Central City, Colorado. As he leaves his hometown to journey west, Hawley contemplates leaving “a good home, society, and all that I hold most dear, to go to a wilderness where I must for a time be deprived of all such enjoyments.” Once in Colorado, he recounts his life as a miner and all the excitements that come with life in the wild West including gunfights, executions, and illness, along with both his successes and failures as a gold miner. The journal covers two years of experiences in Colorado, ending on New Year's Eve 1861. Even though the journal ends there, Hawley’s story continues in the records. He picked up a job with a grocer in Central City, and later opened his own shop on March 8, 1880: Hawley Merchandise Company. The business closed in 1928 but the original location for Hawley Merchandise Company is still standing today. While the business inside is now an antiques shop, paint along the roofline and on the facade read out “THE HAWLEY MDSE CO” and “Groceries Boots & Shoes” pays tribute to the building’s history.

Immigrants from all over the world flocked to boom towns like Central City throughout the 19th century to participate in the Gold Rush. As I continued my research, I was able to get in contact with Don Mattivi Jr. whose family immigrated to Central City from northern Italy in the 1890s. Over the years, the Mattivis worked as miners in several gold mines, used their private home on Gregory Street as a boarding home and hostel, and ran a successful restaurant and cafe that catered to the Opera House patrons out of the old Masonic Hall. The Mattivi family’s success shows how immigrant families were the backbone of early Central City and worked hard to help create the thriving mining town and cultural center that we know today. The current generations of diverse immigrant families are constantly working to maintain their historic heritage. Don Mattivi Jr. served as the Chairman of Historic Preservation and was the mayor of Central City from 1993 to 2003. Throughout his career, he has worked to preserve the physical landscape of the town during the legalization and introduction of gambling in the late 1990s. This family of Italian immigrants has made a lasting impact on Central City, and are just one example of the many others who are so important to the history of this state.

WPA visitors to Central City in the mid-1900s also overlooked women's lives and experiences. While looking for information on the Central City Opera House, I came across a pair of opera glasses, on display at the Center for Colorado Women’s History in Denver, belonging to Ann Evans, a philanthropist who was a dedicated patron of the arts. She was one of three women who spearheaded a volunteer campaign to restore the Opera House to its full glory in 1932 and later became the Chair of the Central City Opera House Association. Evans, along with Ida McFarlane and Edna Chappelle, are responsible for Central City’s return to prominence in the 1930s. Ida McFarlane was an English professor at the University of Denver and negotiated the donation of the Central City Opera House to the University in 1931, allowing the renovations to begin. Edna James Chappell was an actress and devoted patron of the theater who helped Evans and McFarlane found the Central City Opera House Association. An oral history in the collection recalled Ann Evans as a powerful woman: “there was no doubt who was boss.” As a notable supporter of the arts, Ann Evans helped Central City to become the cultural powerhouse that the WPA wrote about, yet her name only pops up in a short newspaper clipping stapled to the back of one of the pages of the ledger. The three women appear briefly under headlines in the Denver Post in the 1930s, yet there is no mention of them in the WPA ledgers. Despite their popularity and cultural contributions, the names of the women involved in restoring the old mining town to cultural prestige were left out by the WPA writers.

Change and Continuity in Central City

Much of what the WPA documented in Central City remains preserved, and on a recent trip to town, I saw first-hand the evidence of Central City’s many ups and downs. Today, businesses thrive (including dispensaries, gift shops, and casinos) while other buildings are boarded up with “for lease” signs on the windows. Central City took the opportunity to use the vacant, rotting, wooden structures dotted along the hillsides to serve as reminders of the once prosperous gold mining industry that transformed Central City into a powerful cultural and political hub. Residents have preserved these buildings through the ages and proved that it is not just the rich and powerful who matter to modern-day Central City.

While most of the traffic through Central City are travelers making their way to the mountain towns in the Colorado high country, the small town is actively celebrating its history. Plaques outside of abandoned buildings show their importance to Central City's history. They represent all orders of society in Central City including fraternal organizations, small businesses, government offices, saloons and taverns for miners, and more. The town has marked buildings not only with names of current businesses, but also past ones and construction dates, paying tribute to the people and pioneers who have come before.

Main Street, Central City. Circa 1870s.

Central City’s Main St. on March 19, 2023.

Central City National Landmark District Sign, March 19, 2023.

Bonanza Casino on Main St., March 19, 2023.

Records like those the WPA visitors created enliven History Colorado’s collection and allow researchers and history buffs alike to explore hidden stories that have been otherwise untold. From objects and artifacts to archives and photographs, each collection has a unique history and fascinating future. The WPA ledgers have been a great entry point and have allowed me to dive into the history of Central City and opened up so many more revenues of interesting research. The Central City Guide along with the other City Guides from the Federal Writers’ Program are now available to the public on History Colorado's website: h-co.org/collections. I would like to thank the Colorado Historical Records Advisory Board for making this project possible.