Story

The Wizard in the Mountains

Nikola Tesla’s mysterious experiments in Colorado Springs are still raising questions 123 years later.

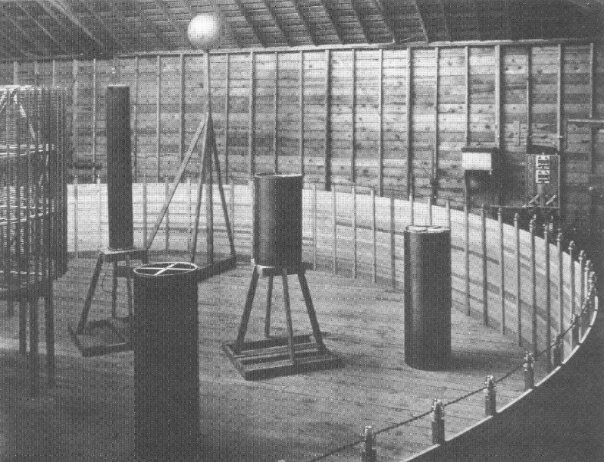

A photograph of Tesla’s Colorado Springs Laboratory. The opening roof and 142-foot pole can clearly be seen atop the small barn structure. Signposts warning of danger can also be seen near the entrance.

Having grown up in Colorado, and being an avid fan of Nikola Tesla, I was only too thrilled to discover that the famous inventor and physicist had briefly lived in Colorado Springs. Like many people, I became fascinated with the mysteries surrounding Tesla’s work, especially from a physics perspective (as I am a physics writer). During my time in graduate school, I had written several articles about Tesla’s notes that, at the time, had recently been released by the FBI. My interest in Tesla only grew as I dug through these digital vaults. So, when I found out that he spent time in Colorado Springs, I had to find out why he came, and more importantly, why he left after less than a year.

Drive through Colorado Spring today and it’s hard to imagine what the town would have been like over 100 years ago. Between the AirForce Academy and the parade of shops and restaurants dotting I-25, it can be hard to appreciate the city’s history. Today it’s next to impossible to find any evidence of Tesla’s visit unless you look really hard. Yet, historians and Tesla scholars alike believe that his visit to Colorado Springs was one of the most productive and important times in his career, as it helped him come up with some of the fundamental ideas for the wireless transfer of energy. Stories of his barn-like laboratory shooting feet-long sparks into the sky or how he trapped himself under a live Tesla coil remain out of the mainstream narrative of Colorado Springs history, though they explain how the then-rural town dealt with the visit of one of its first celebrities.

Tesla was a Serbian engineer and scientist who was already famous and well-funded by the time he arrived in Colorado. In the 1880s, with George Westinghouse’s help, Tesla won the “current wars” against Thomas Edison, wherein the entire city of Buffalo, New York, was lit up using the alternating currents coming from Niagara Falls. He worked on several other experiments, including one that unfortunately burned his laboratory down in 1895. Tesla was not deterred, however. By the time Tesla boarded a train for Colorado, he had given lectures at several Ivy League universities, and colleges in London, securing his reputation as a successful scientist.

A photograph image of Nikola Tesla circa 1890 at age 34.

Heading West

Like much of his research, moving to Colorado Springs in May of 1899 was a calculated risk for Tesla. Through his prior work at the Westinghouse company, Tesla met a lawyer named Leonard Curtis, who had shares in the El Paso Electric Company in Colorado Springs. Curtis knew Tesla was looking for a new laboratory and offered him a discounted property in Colorado Springs and free electricity from the electric company. With fewer safety hazards and more room in Colorado, it was an offer Tesla could not refuse. As he boarded the train for Colorado Springs, he told his laboratory assistants to send his equipment immediately behind him.

He was excited to see whether Colorado’s thin air was more conductive for electricity. Tesla planned to place various electrical towers around Colorado and other mountainous areas in order totransmit energy between them, similar to how satellites work today. Perhaps Tesla thought he would build the first of these electric towers in the Rocky Mountains.

After a short stop in Chicago, Tesla arrived at the then-rural town and was immediately swarmed by local reporters. “When word [broke] out that he [was] coming, there [was] a sensation,” explained Leah Witherow, History Curator at the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum. “People [were] interested in what he [was] going to do here, what he [was] like.” Flustered, Tesla scurried past the reporters and continued to avoid them throughout his visit.

Colorado Springs’ main draws haven’t changed much since its founding in 1871. Upper-class families made the trek from the east coast to the Rockies for the mountain views, the fresh dry air, and the invigorating lifestyle. As Leah Witherow, Curator for the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum, explains, “Colorado Springs advertised itself as America’s greatest sanitarium. We lured people here to recuperate from consumption, [which] today we call tuberculosis. It was the leading cause of death in the 19th century.”

The Springs’ reputation for healthy living attracted people from all over the world, specifically, from Europe and England, but also the east coast. Visitors often invested in the local mining businesses and some quickly struck gold. They then built sprawling mansions around the mountain town using their newly gained wealth. In fact, so many Europeans visited Colorado Springs that the town gained the nickname “Little London.” While Tesla’s European background undoubtedly helped him blend in with the tourists, his celebrity status made him stick out like a sore thumb.

However hard he tried to hide from the press, Tesla’s famous idiosyncrasies became prevalent during the inventor’s stay. His room at the luxurious Alta Vista hotel was number 207, a “lucky” number according to Tesla as 2+7=9, a sum divisible by 3. He also ordered eighteen fresh towels to his room daily, which raised a few eyebrows. Tesla’s germaphobe tendencies were progressive for his time, as he maintained better health than some of his peers, though had redder and rawer hands to show for it. Some contemporary experts posit these were symptoms of autistic behavior, but the hotel overlooked Tesla’s quirks in the late nineteenth century because his presence attracted curious locals. “Having someone famous in Colorado Springs [was] a great marketing tool,” according to Lea Witherow.

Though the hotel offered many indulgences, from a beautiful brick portico to delicious cuisine, Tesla barely spent time there. This was out of the ordinary for most hotel guests, as the looming castle-like hotel provided a high caliber of warmth and comfort that starkly contrasted with the cold and rugged landscape. But Tesla practically lived in his laboratory.

“It has been said that he initially walk[ed] to his laboratory outside Colorado Springs proper. And people would follow him or show up in his laboratory,” added Witherow. “They would want to go inside, but he wasn’t interested in entertaining visitors. He barely had the patience for reporters, but he also knew reporters would help to describe his work and spread his name.”

He remained a mystery for the duration of his visit, and for the centuries afterwards, individuals like me continue to dig into his fascinating Colorado Springs journey. Tesla and his small team even erected a fence to avoid onlookers and put warning signs alongside it. One sign quoted Dante’s Inferno: “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here,” but it did little to deter the many curious eyes peeking into the laboratory.

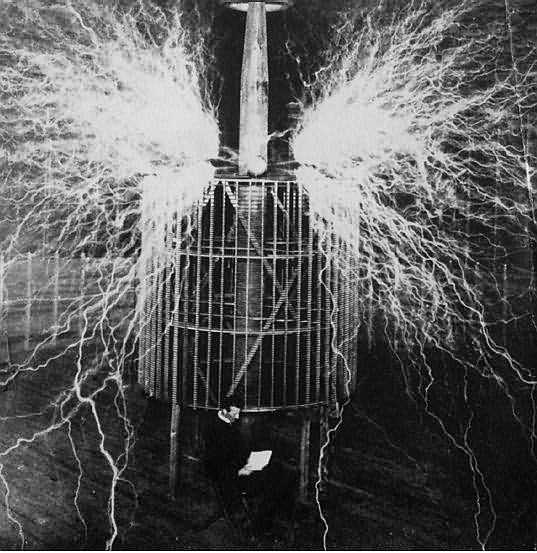

This double-exposure image makes it seem like Tesla sits right next to an active Tesla coil. Thanks to stunt photographer Dickinson V. Alley, this photograph combined two images to create an eye-catching and shocking image. Tesla later used this image to showcase his work.

Conducting Electricity Through the Atmosphere

Tesla’s “laboratory” looked more like a barn built in the middle of nowhere. A local carpenter named Joseph Dozier constructed the building to accommodate Tesla’s strange requests, including a wooden roof that rolled back to prevent the lab from catching fire. Because Tesla was in a hurry to start his research, he rushed Dozier into building the laboratory, the result of which was a rather dilapidated building looking like it might collapse at any moment. In the photos of Tesla’s laboratory during the time, the scaffolding around the building remained throughout his entire visit.

In the middle of the structure stood a 142-foot pole with a giant copper ball on the top. In later experiments, this ball would shoot sparks into Colorado’s thin atmosphere, giving locals quite the light show. As writer Margaret Cheney described in her book Tesla: A Man Out of Time: “It did not take long for the word to spread that the apparatus being built by Mr. Tesla was capable of killing a hundred persons in a single flash of lightning.” This was just one of many rumors that would grow from Tesla’s visit to Colorado Springs, rumors that I and other scholars have had to untangle to find what Tesla was actually up to.

Inside the fifty-by-sixty-foot barn, a goliath Tesla coil measuring fifty-two feet across loomed over the rest of the laboratory and would have made the dilapidated building feel cramped. It was Tesla’s biggest coil and proved essential for his many experiments. A Tesla coil works by using a primary and secondary coil, both complete with areas to store electricity (known as capacitors). The two coils can then connect through the air via a “spark gap” or a gap between the two electrodes (or coils) that produces the electricity. Thanks to the spark gap, the two coils and their capacitors create a giant circuit that is connected via this gap in the air. Because electricity is moving through the air, it ionizes air molecules, splitting up nitrogen and oxygen molecules to produce ozone gas. I’ve smelled the ozone gas when I play with my own small Tesla coil at home. Because ozone is toxic to breathe in, I try to use my own coil as little as possible, but for figures like Tesla who had no idea about ozone’s toxicity, he would have no doubt gotten used to its pungent odor.

Tesla had studied and validated his wireless energy transfer hypothesis in New York and hoped to reproduce the process on a bigger scale as he worked to harness Colorado’s thin atmosphere to transfer electricity from one apparatus to another. According to W. Bernard Carlson in Tesla: The Inventor of the Electrical Age: “With his larger magnifying transmitter [the Tesla coil] in Colorado, he hoped to generate fifty million volts [of electricity] and produce artificial lightning bolts between fifty and one hundred feet long.” These long bolts often threatened to set the barn on fire and did so a couple of times. In one instance, Tesla found himself trapped underneath a live coil. By crawling on his hands and knees, he was able to escape, though did so in a fit of coughing from the ozone gas produced by the coil. He learned from his previous mistakes and soon took advantage of the mobile roof.

Tesla took immaculate-yet-incomplete notes in a diary during his visit, performing his experiments in the evening when the local power grid was less busy. The darkness made his experiments all the more dramatic as he used his giant Tesla coil, tall pole, and copper ball to send electricity into the atmosphere. “The noises became machine-gun staccato—then roared to artillery intensity,” described scholars Inez Hunt and Wanetta W. Draper in their book Lightning in His Hand. “Ghostly sparks danced a macabre routine all over the laboratory. There was the smell of sulfur that might be coming from hell itself.”

Tesla was thrilled by how many artificial lightning bolts he could produce and how far they stretched. After monitoring many brief lightning storms during the summer of 1899, Tesla began to understand how lightning moved throughout the dry atmosphere in the mountains. He wrote in his diary: “Colorado is a country famous for its natural displays of electrical force...aided by the dryness and rarefaction of the air, the water evaporates as in a boiler and static electricity is developed in abundance.” This electrical transfer from the atmosphere to the ground via lightning would influence how future researchers study wireless energy transfer.

While Tesla remained wary of reporters and onlookers at his laboratory, he did allow one photographer to visit his laboratory. Dickenson V. Alley was a promotional stunt photographer from the east coast who would take some of the most well-known photos of the inventor. Using a double exposure trick with his camera, Alley created one-of-a-kind images of Tesla at work in his laboratory. The first photograph would be of Tesla sitting in his chair, reading a paper. Using the same photographic plate, Alley would take a photo in the exact location, this time with the Tesla coil active. The final photograph combined the two images to reveal Tesla sitting beside his coil erupting in a lightning shower. Tesla later used this image in his lectures to promote his research and garner funding.

Another photograph of Tesla’s Colorado Springs Laboratory taken from a different angle. The looming Union Printers Home can be seen in the background. From this angle, different scaffolding and observation platforms stand over the barn.

Some of Alley’s other images revealed the success of Tesla’s experiments. He captured one of Tesla’s oscillators, another device wedged into the ground, surrounded by lit incandescent bulbs. From this image, the viewer could deduce that Tesla was conducting electricity through the Earth to light the bulbs. As all the photos were taken during the winter of 1899, Tesla and Alley worked in freezing conditions to catch artificial lightning on camera. Because Tesla injected electricity into the ground, the atmosphere around his laboratory became even more mysterious. Butterflies flitting around the laboratory seemed disoriented, and passers-by often heard sparks crackling between their shoes. This only added to Tesla’s bizarre reputation around Colorado Springs. In the end, Alley produced sixty-eight photographs of Tesla’s Colorado laboratory, all inspiring curiosity in Tesla fans today.

While Tesla didn’t ultimately end up building an electrical station in Colorado Springs to try to wirelessly transfer energy from one part of the world to another (specifically from Pike’s Peak to Paris, as he told one reporter), he was the first to realize how impactful wireless energy could be in the future. Instead of having geographical limitations on where to power your electronic devices, using wireless energy transfer allows you to travel anywhere in the world and still have power. Wireless energy could help rural areas and developing countries have a reliable source of energy. In short, Tesla saw not only a new way to power the world, but a way to help better it.

Even after he left Colorado, Tesla continued to study this process, hoping to find ways to improve energy transfer and make it more controlled. “Tesla was sort of the engineer’s engineer and liked to think way outside the box,” stated Greg E. Leyh, a Tesla coil developer. “He stressed the importance of solving problems in an interdisciplinary context and disregarding conventional limits.”

Studying Stationary Waves

Perhaps the most well-known experiment Tesla performed in Colorado Springs was his work on stationary waves. Stationary waves oscillate but don’t physically move, and Tesla hoped to find these waves inside the Earth’s crust and harness them to transfer electric energy from one source to another. He believed the lightning from the mountain storms deposited electricity into the Earth as a standing wave, which he could try to enhance for powering electrical devices.

As Tesla historian and author W. Bernard Carlson explained in Tesla: The Inventor of the Electrical Age, “Because the numerous New York systems—for telegraphy, telephony, lighting, and transportation—produced too much electrical interference, Tesla had not been able to make any reliable measurements of whether the Earth possessed a natural electrical potential or charge.” But Colorado Springs was an isolated town and the ideal place for Tesla to detect these waves.

To measure the Earth’s electrical potential for standing waves, Tesla created a unique apparatus that held iron filings between two electrical terminals within a glass tube. If the apparatus detected an electrical field, the filings would form a line along the terminals. “The earth was…literally alive with vibrations,” Tesla noted in his diary, “and soon I was deeply absorbed in the interesting investigation.” Using other devices, like his coil, Tesla was able to create his own stationary waves within Earth’s crust, showing that the ground itself could indeed conduct electricity.

While more recent research has shown the limitations of electrical conduction within the Earth, Tesla’s work showcased the possibility of extremely low frequency (ELF) waves conducted between Earth’s surface and the ionosphere, a section of the upper atmosphere.

In his diary, Tesla wrote a prediction about the power of stationary waves, believing they could be used to transmit news reports worldwide. He described: “A cheap and simple device, which might be carried in one’s pocket, may then be set up somewhere on sea or land, and it will record the world’s news or special messages as may be intended for it.” His diary descriptions are eerily similar to the telecommunication signals sent and received by smartphones, computers, and satellites today. “Thus, the entire Earth will be converted into a huge brain, as it were, capable of response in every one of its parts,” he added, not knowing the true extent that humanity's future would bring the potential of these ideas into technology.

Leaving Colorado with More Questions than Answers

Just as suddenly as he arrived, Tesla left Colorado Springs in January 1900. Rumors began circulating that he caused a power outage in Colorado Springs (which soured his relationship with his lawyer friend Leonard Curtis who had shares in the local electric company) and he suddenly had to pay for electricity, which he couldn’t afford. Others suggest he had better funding options back in New York. Some scholars posit that Tesla was satisfied enough with the experiments in stationary waves that he returned to New York to test them at a different laboratory. Either way, most stories report that, without any explanation, Tesla packed his things and boarded a train for the east coast, leaving Tesla scholars and fans like myself wondering, “What actually happened?”

Alley and Tesla took two separate photographs to make this photograph but used the same lens plate to create a double-exposure image. In one image, Tesla sits in front of his large coil, around 52 feet across, the largest one he had built in 1899. In the other image, Tesla fires up the coil and Alley captures the feet-long sparks shooting out of the device.

Tesla’s departure left the townspeople with unresolved questions and expectations. Witherow explained: “He said he would be back, so he hired a caretaker to watch over his laboratory, mainly to keep people out. But he never came back. And after a while, he stopped paying his caretaker. He eventually stopped paying his electricity bills, so the electric company finally began to charge him.” The water company sued Tesla in absentia for lack of payment. After several years, “the sheriff’s department had an auction on the steps of the courthouse where they auctioned off the property,” said Witherow. “The laboratory was dismantled to help pay for his debt, and all of the equipment inside was also sold to pay off his debts.”

Due to the auction, it’s been challenging for scholars like Witherow to track where Tesla’s possessions have ended up. “We do have a small Tesla exhibit, but we don’t have any original objects,” said Witherow about the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum. She believes any possible reconstruction of Tesla’s laboratory in Colorado Springs is unlikely. “We [can’t] pinpoint a location exactly [of Tesla’s old laboratory] because it is now occupied by private homeowners,” she added. “I know over the years that the homeowners have been approached countless times by people who come knocking to see the sight of Tesla’s laboratory.” A plaque is all that remains to commemorate Tesla's impact on the then-rural town. You can find it in the Knob Hill area of Colorado Springs, if you look hard enough.

Scholars like Witherow believe Tesla’s mysterious visit and hasty departure left Colorado Springs locals with a bitter taste in their mouths and a poor impression of the inventor. “He had gone from being an object of curiosity to an object of enmity because people were angry that he didn’t live up to his promises [of returning],” she said. However, in the 123 years since his visit, local opinions about Tesla’s visit have shifted. “Many people are proud that he conducted some of his experiments here,” she added. “So, he’s a point of pride. Whereas, you know, 120 years ago, he was a point of contention.”

Tesla didn’t publish papers or file patents during his visit, two ways he might have helped prove the impact of his research in the mountain town. Because he was an extreme perfectionist, Tesla couldn’t bear the idea of publishing his work until it had passed his own rigorous standards. This has left little in the way of physical evidence of his time in the mountains, and due to the gaps in Tesla’s own writing, his visit leaves historians and locals alike with more questions than answers. Rumors have made Tesla appear as a larger-than-life character, a wizard of electricity with immense power, making it hard to understand what happened during his time in Colorado Springs. Did Tesla actually cause a town-wide power outage? Was Colorado’s thin atmosphere actually helpful for the wireless transfer of energy? These questions, and many others, will permanently haunt Tesla scholars and fans alike when looking at his time in Colorado. From my own research, I believe that Colorado’s atmosphere was indeed helpful for Tesla’s work, as many accounts seem to indicate. We don’t have any similar experiments of Tesla’s to compare his results, and the most similar structure, his wireless tower in Wardenclyffe, New York, was never completed since he ran out of funding before it could be tested. Whatever he accomplished here, Tesla’s diary shows that he conducted some of his most impactful work in the West.

Tesla’s Colorado Springs Laboratory layout shows just how cramped it was. This central area of the barn was dedicated to Tesla’s largest coil and magnifiers and receivers. Other areas of the laboratory included a small back office.

A Scientific Legacy

Dr. Khurram Khan Afridi, an Associate Professor at Cornell University, is impressed by Tesla’s impact in Colorado Springs regardless of whether or not his experiments ever bore practical results. Before arriving at Cornell University, Afridi worked at the University of Colorado Boulder, studying the wireless transfer of energy. “My [wireless charging] work is deeply inspired by Nikola Tesla’s work,” Afridi stated. “I’ve been his fan for as long as I can remember.”

Today, scientists like Afridi are researching the same wireless energy transfer via magnetic fields that Tesla was working on over a century ago. “Ninety-nine percent of the people and probably ninety-nine percent of the products out there utilize [magnetic fields,]” he elaborated.

The main challenge with transferring energy via electric fields (a process known as the capacitance approach) compared to using magnetic fields (known as the induction approach) is due to the space between the sender and the receiver. The longer the distance between the energy’s source and its terminal, the smaller the capacitance, or ability to store electric charge. This can make it difficult for researchers developing wireless charging devices for smartphones or electric cars to get a full charge.

Despite the difficulty, Afridi hopes to transfer energy via electric fields similar to Tesla’s experiments. “He essentially had a sort of spark gap,” Afridi explained. “I don’t know precisely what apparatus he was using to produce the high voltage, high-frequency kind of electricity, but he would get the lights turned off, and then he’d put a fluorescent lamp between them, and it would light up without contact and awe the audience. That is the same phenomenon I’m leveraging in my work.”

Because electric fields travel in relatively straight lines, Afridi believes that he can lower the cost of the entire system by taking advantage of this process. In his research at CU Boulder and now at Cornell, he has shown initial success in his system by increasing the frequency of the electric fields. “Apart from Tesla being an inspiration in general, for all of his various inventions, and the fact that he was a true nerd… it is also sort of a very close connection in terms of the kinds of demonstrations he was doing.”

While at CU Boulder, Afridi felt more connected to Tesla because of his visit to Colorado Springs. “I did feel a closer connection to Tesla,” he added. “In fact, it’s actually interesting that I’ve now lived or worked in both the states that Tesla worked in, or at least he’s known for: New York and Colorado. When I did move to Colorado, that was one of the things that was in the back of my mind: that I was actually moving to a place where Tesla spent some time.” Tesla’s visit to Colorado Springs created a paradigm shift in Colorado’s history. “Tesla absolutely has become part and parcel of Colorado Springs’ story,” Witherow explained. “Many famous people have come here over time, but perhaps no one as famous as Nikola Tesla. He contributed so much scientific knowledge to the world, but he also left so many questions because he was truly a mystery. He had fantastical ideas. There are still so many questions surrounding him that, I think, it’s a point of pride having come to Colorado Springs. He was born in Europe and did most of his scientific work in New York and New Jersey, so he came to Colorado Springs [specifically] to research…He’s part of our story, even if he was here less than a year.”

A plaque is all that remains of Tesla’s visit to Colorado Springs. The plaque summarizes the history of Tesla’s visit, and highlights his importance to Colorado Springs history. As the plaque was placed where the laboratory once stood, one can see where the landscape has significantly changed due to urban development.